migraine

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| G43.0 | Migraines without aura (common migraines) |

| G43.1 | Migraines with aura (classic migraines) |

| G43.2 | Status migraenosus |

| G43.3 | Complicated migraines |

| G43.8 | Other migraines |

| G43.9 | Migraine, unspecified |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The migraine (like french migraine transmitted latin hemigrania , unilateral headache of ancient Greek ἡμικρανία hemikrania , German , headache on one side, migraine ' , this one from ancient Greek ἡμι Hemi , German , half' as well as ancient Greek κρανίον Kranion , German , skull ' ) is a neurological disease that affects around 10% of the population. It occurs about three times as often in women as in men, but before puberty it is evenly distributed between the sexes and has a diverse clinical picture. In adults, it is typically characterized by periodically recurring, seizure-like, pulsating and unilateral headache , which can be accompanied by additional symptoms such as nausea , vomiting , sensitivity to light ( photophobia ) or sensitivity to noise ( phonophobia ). In some patients, a migraine attack is preceded by a migraine aura, during which visual or sensory disturbances in particular occur. However, motor disorders are also possible. After excluding other diseases as causes, the diagnosis is usually made with the help of an anamnesis .

Epidemiology

| | |

Around eight million people in Germany suffer from migraines. Statistically speaking, women ( prevalence 18%) are more frequently affected than men (prevalence 6%). In other western countries, such as other European countries and the USA, a comparable frequency of migraines is reported, while in South America, Asia and Africa slightly fewer people suffer from migraines.

Migraines are most commonly found in people between the ages of 25 and 45. The disease can begin in childhood, new studies are linking migraines with childhood colic, which could also be a type of migraine. In the final year of primary school, up to 80% of all children complain of headaches. About 12% of them report symptoms that are compatible with a diagnosis of migraine. By puberty, the proportion increases to 20%. Before sexual maturity, there is statistically no difference between the sexes with regard to the risk of the disease. Only with puberty and synchronously with the development of sexual function does the prevalence increase in the female sex. However, a higher especially in men who frequently suffer from non-classical forms of migraine unreported accepted.

Due to its frequency, migraines are of economic importance that should not be underestimated . Every year in Germany around 500 million euros are spent as direct costs by patients and health insurance companies for medical and drug treatment of migraines. The additional indirect costs resulting from lost work and productivity restrictions are estimated to be over ten times this sum.

Symptoms

During a migraine attack, different phases with different characteristic symptoms can be passed through. A seizure is often heralded by a harbinger or prodromal phase with harbinger symptoms . This can be followed by a phase of perception disorders, the so-called migraine aura , which particularly affect vision. In the headache phase, in addition to the headache, there are various other symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light, noise and smell. In some patients, the migraine attack lasts after the headache subsides. This phase is known as the recovery phase.

Harbinger phase

In at least 30% of migraine patients, a migraine attack announces itself early in the form of harbinger symptoms. The harbinger phase can precede a migraine attack by a few hours to two days and lasts for one to two hours in most patients. During the harbinger phase, psychological, neurological and vegetative symptoms in particular appear that differ from those of the aura phase. The most common are fatigue, sensitivity to noise and frequent yawning. Often there are also disorders in the gastrointestinal tract that can include constipation . Many patients are characterized by a craving for certain foods, which is usually misinterpreted as a migraine trigger. Many patients do not see a connection between these symptoms and a later migraine attack. Therefore, the frequency of these symptoms as harbingers of a migraine attack may be significantly underestimated.

Aura phase

- Visual symptoms of a migraine aura

Fortification with zigzag structures reminiscent of a fort

Migraines are accompanied by an aura in around 15% to 20% of cases. In the aura phase, mostly visual disturbances such as scotomas , fortifications, loss of spatial vision and blurring or sensory disturbances such as loss of touch or tingling in the arms, legs and face are felt, which start slowly and then completely subside. In addition, disorders of the sense of smell, balance disorders, speech disorders or other neurological deficits can occur. The aura is perceived and described differently from patient to patient. Auras with a strong visual expression, as they can occur in the context of a migraine, are also known as Alice in Wonderland syndrome . Some famous migraine sufferers were inspired by visual phenomena during the aura phase for their artistic work.

The dynamics of the process are characteristic of migraine auras, for example the "wandering" of the flickering scotoma in the visual field or the wandering of the tingling sensation in the arm or through the individual fingers. A shift in the aura symptoms, for example from vision to sensitivity to speech disorders and symptoms of paralysis, can also be observed. This dynamic is shown in measurements in the brain in the form of a wandering disturbance front ( scattered polarization ). The dynamics of the symptoms as well as their slow onset and resolution are an important distinguishing feature from other neurological diseases, especially from a stroke . The aura does not have any damaging effects on brain tissue, its signs are only temporary and usually last up to 60 minutes.

Auras can occur in individual cases without a subsequent headache phase.

Headache phase

In the headache phase , the headache usually occurs on one side (around 70% of cases), particularly in the forehead, temple and eye area. It is usually pulsating and increases in intensity with exercise, while rest and darkness help relieve headaches. The headache of a migraine attack is often accompanied by additional symptoms such as loss of appetite (> 80%), nausea (80%), vomiting (40% to 50%) as well as photophobia (60%), phonophobia (50%) and, less often, osmophobia (sensitivity to smell, < 10% to 30%). The patient is pale and does not endure external influences such as light and noise, as these aggravate his symptoms. The duration of the headache phase varies between 60 minutes and up to three days, depending on the patient and the type of migraine. Children have shorter migraine attacks with more localization in the forehead and temporal region on both sides. Concomitant symptoms in children and adolescents are more frequent odor sensitivity, dizziness and balance disorders. Some special forms of migraines can occur without a headache.

Regression phase

In the regression phase, the migraine headache and accompanying symptoms slowly decrease until complete recovery. The patient feels tired and tense. This phase can take up to 24 hours.

Triggering factors

Since the prevalence of migraines in industrialized countries has increased by a factor of two to three over the past 40 years, it can be assumed that environmental factors and lifestyle play an essential role in the development of migraines. Migraines can be triggered in sensitive people by special situations or substances, so-called triggers ( key stimuli ). These include, in particular, hormonal factors, sleep , stress , food and environmental factors . These trigger factors, however, are very different from one individual to the next and can be found out with the help of a headache diary .

The most common triggers of a migraine include stress, irregular biorhythms with a lack of sleep or too much sleep and environmental factors. With some migraine patients, a migraine attack only occurs in the post-stress relaxation phase (“weekend migraine”). In addition to odor stimuli, weather fluctuations are often mentioned as external factors that can trigger a migraine attack. The thermometer value is less relevant than the perceived temperature. This is made up of humidity, air temperature, radiant heat, heat reflection and wind.

One of the most important trigger factors in women is hormonal fluctuations. Over half of all female migraineurs cite the menstrual cycle as the trigger for a migraine. A migraine attack can in particular during the late luteal phase of the cycle or during the tablet-free period contraception with oral contraceptives occur.

Around two thirds of all migraine sufferers see a connection between the consumption of certain foods and luxury foods and the triggering of a migraine attack. The most important migraine trigger in this group is alcohol . In addition, foods and luxury goods containing glutamate , tyramine , histamine and serotonin, such as red wine , chocolate and cheese, are named as trigger factors. Even coffee is often perceived as a triggering factor. However, many patients misinterpret an increased appetite for certain foods, which is a well-known harbinger of an already looming migraine attack, as a trigger factor. Thus, many of the diet-related factors are overstated as a cause. A regular diet without skipping meals appears to be more important.

Some drugs , especially substances that release nitric oxide and expand blood vessels ( vasodilators ), can induce a migraine attack.

Division and classification

| Classification of migraines according to the IHS directive |

|

|---|---|

| 1. | Migraines without aura (common migraines) |

| 2. | Migraines with aura (classic migraines) |

| 2.1. | Typical aura with migraine headache |

| 2.2. | Typical aura with non-migraine headache |

| 2.3. | Typical aura without a headache |

| 2.4. | Familial hemiplegic migraines |

| 2.5. | Sporadic hemiplegic migraines |

| 2.6. | Basilar-type migraines |

| 3. | Periodic syndromes in childhood that are generally precursors to migraines |

| 3.1. | Cyclical vomiting |

| 3.2. | Abdominal migraines |

| 3.3. | Childhood benign paroxysmal dizziness |

| 4th | Retinal migraines |

| 5. | Migraine Complications |

| 5.1. | Chronic migraines |

| 5.2. | Status migraine |

| 5.3. | Persistent aura without a cerebral infarction |

| 5.4. | Migrainous infarction |

| 5.5. | Cerebral seizures triggered by migraines |

| 6th | Probable migraines (migraine-like disorder) |

| 6.1. | Probable migraines without aura |

| 6.2. | Probable migraines with aura |

| 6.3. | Likely chronic migraines |

Like tension headache and cluster headache, migraine is a primary headache disorder. That is, it is not the obvious consequence of other diseases such as brain tumors , brain trauma , cerebral haemorrhage, or inflammation .

Galen von Pergamon already distinguished at least 4 different types of headache, one of which he called "hemicrania" (pulsating, one-sided, paroxysmal), from which the term migraine is derived. Jason Pratensis (1486–1558) distinguished in his book "De cerebri morbis" 9 different headaches, u. a. also the hemicrania. Thomas Willis (1621–1675) differentiated headaches according to location and time pattern. In 1962 an ad-hoc committee of the NINDS, at the instigation of Harold Wolff (1898–1962) in the USA, published the first systematic classification with 15 types of headache. Since 1988, the classification of migraines and migraine-like diseases has been purely phenomenological according to the guidelines of the International Headache Society (IHS) primarily on the basis of the occurrence or absence of a migraine aura. Edition 1 of the ICHD appeared in 1988; Edition 2 in 2004, Edition 3 in 2018. e

Migraines without aura (common migraines)

The migraine without aura is the most common form of migraine, accounting for around 80% to 85% of migraine attacks. A migraine without aura can be said to have occurred if at least five migraine attacks occurred in the medical history in which at least two of the four main criteria are met and the headache phase was not preceded by an aura:

- Hemicrania (one-sided headache), changing sides is possible

- moderate to severe pain intensity

- pulsating or throbbing pain character

- Reinforcement through physical activity

In addition, there must be at least one vegetative symptom, i.e. nausea and optionally vomiting or phonophobia and photophobia. Even though an aura phase is missing, harbingers such as restlessness, states of excitement and mood changes can occur. These show up a few hours to two days before the actual attack. In 2/3 of the cases the headache is unilateral and pulsating, increases with physical activity and can last between 4 hours and 3 days if left untreated. Concomitant symptoms such as nausea or vomiting (80%), sensitivity to light (60%), sensitivity to noise (50%) and sensitivity to smell (<30%) can occur. In children, the duration of the migraine may be shortened. Instead, the headache is usually localized on both sides. In women, migraines without aura are often closely related to menstruation . Newer guidelines therefore differentiate between a non-menstrual, a menstruation-associated and a purely menstrual migraine without aura.

Migraines with aura (classic migraines)

A migraine with aura is characterized by reversible neurological symptoms that include visual disturbances with visual field defects, scotomas, flashes of light or the perception of colorful, iridescent, jagged lines or flickering, sensory disturbances with tingling or numbness and speech disorders. Occasionally (6%) there are also motor disturbances up to paralysis. These aura symptoms last an average of 20 to 30 minutes, rarely more than an hour. During the aura, no later than 60 minutes later, a headache phase usually occurs that corresponds to the migraine without aura and can be accompanied by symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light and noise. As in the case of the typical aura without a headache, this headache phase can be completely absent.

According to the IHS criteria, a migraine with aura is spoken of if the following criteria are met:

- completely reversible visual disturbances, sensory disturbances or speech disturbances

- Slowly developing or releasing aura symptoms lasting 5 to 60 minutes

Typical aura with migraine headache

The typical aura with migraine headache is the most common form of migraine with aura. In addition, in many patients the aura is followed by a headache that does not meet the criteria of a migraine headache. The headache is then non-pulsating, one-sided and accompanied by additional symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light and noise.

Typical aura without a headache

While most migraine auras are followed by a headache, a minority of patients will experience an aura that meets the above criteria without a headache. This type of migraine is particularly common in men. In addition, with increasing age, a typical aura with a migraine headache may change into a typical aura without a migraine headache in migraine sufferers.

Familial hemiplegic migraines

In addition to the above-mentioned typical symptoms of a migraine with aura, motor disorders can often be observed in the rare but familial hemiplegic migraine. Symptoms that are characteristic of a basilar migraine , as well as disturbances of consciousness up to coma, fever and states of confusion can also occur. The most important criterion for the diagnosis is that at least one first or second degree relative also has migraine attacks with the symptoms of a familial hemiplegic migraine. Three genetic defects localized on chromosomes 1 , 2 and 19 have so far been found to be a cause of the familial hemiplegic migraine . Based on the location of the genetic defects, a distinction can be made between types I (FMH1), II (FMH2) and III (FMH3) of familial hemiplegic migraine.

Sporadic hemiplegic migraines

The symptoms of sporadic hemiplegic migraine are similar to those of familial hemiplegic migraine. The most important differentiating criterion compared to familial hemiplegic migraine is the absence of comparable cases in the first and second degree relationship. Also, the sporadic hemiplegic migraine cannot be attributed to genetic defects as a cause. Men are particularly affected by sporadic hemiplegic migraines. Their frequency is comparable to that of familial hemiplegic migraines.

Basilar-type migraines

Basilar-type migraines, also known as basilar migraines, are more common in young adults. The neurological symptoms of a basilar-type migraine may differ from the aforementioned aura symptoms. Characteristic symptoms are speech disorders, dizziness , tinnitus , hearing impairment, double vision, visual disturbances in both the temporal and nasal visual fields of both eyes, ataxia , impaired consciousness or simultaneous paresthesia on both sides . In individual cases a locked-in syndrome occurs : complete immobility with conscious awareness for a period of 2 to 30 minutes, occasionally vertical eye movements are still possible ( Bickerstaff syndrome ). Furthermore, the one Alice in Wonderland syndrome on the possible symptoms. Both the aura symptoms and the migraine headache are mostly perceived on both sides. Involvement of the eponymous basilar artery is suspected, but has not been confirmed.

Retinal migraines

Characteristic for a retinal migraine are unilateral aura-like visual phenomena such as scotomas, fibrillation or blindness, which are limited to the time of the migraine attack. During these visual disturbances or for up to 60 minutes afterwards, the migraine headache phase begins.

Probable migraines

According to the IHS, one speaks of a probable migraine if all the criteria for diagnosing a migraine without aura or a migraine with aura are met with the exception of one criterion. A classification as probable migraine should also be made if the aforementioned criteria for a migraine with or without aura were met, but also acute medication was taken in an amount that does not exclude a drug-induced headache.

Migraine Complications

Chronic migraines

If a patient suffers from a migraine more than 15 days a month for several months (≥ 3), it is called a chronic migraine. Chronic migraines are often a complication of migraines without aura and are observed in increasing cases. A chronic migraine is to be distinguished from the chronic headache when taking medication, which is induced, for example, by overuse of analgesics .

Status migraenosus

With a status migraenosus, a migraine attack immediately passes over into the next one or the migraine symptoms do not decrease after 72 hours. The patient hardly has any recovery time and the level of suffering is correspondingly high.

Migrainous infarction

The migraine infarct is a cerebral infarction in the course of a typical migraine attack with aura. Characteristically, one or more aura symptoms appear that last longer than 60 minutes. With the help of imaging methods, an ischemic stroke can be detected in relevant parts of the brain. Cerebral infarctions for other reasons with simultaneous migraines and cerebral infarctions for other reasons with migraine-like symptoms must be distinguished from a migraine attack. Women under the age of 45 are particularly affected by a migraine attack.

Persistent aura without infarction

The rare persistent aura without an infarction is characterized by aura symptoms that persist for more than a week without a cerebral infarction being detected radiologically. The aura symptoms are mostly perceived on both sides. In contrast to a migraine attack, the brain is not permanently damaged.

Migralepsy

Migralepsy is understood to be cerebral seizures that are triggered by a migraine. It is a complication of auric migraine and shows the complex connections between migraines and epilepsy . An epileptic seizure occurs during or within 60 minutes of an aura phase.

Visual Snow

Visual Snow is a complex of complaints that appears to be epidemiologically associated with migraines with aura. The clinical picture is accompanied by persistent image noise in the entire field of vision, similar to a persistent migraine aura, which is why it is often misinterpreted as such.

diagnosis

Migraine is a disease that is diagnosed on the basis of the symptoms. The diagnosis of migraine is made by questioning the patient with a medical history ( anamnesis ). For this purpose, a headache diary can be kept and the degree of impairment ( Migraine Disability Assessment Score ) documented. A general physical examination also helps determine the diagnosis by excluding other diseases as a cause of headache and plays an important role in the selection of medication. Laboratory examinations and apparatus-based examination methods do not contribute to the direct diagnosis of migraines in practice, but are only required if another disease is to be unequivocally excluded.

First and foremost, a distinction must be made between the diagnosis of secondary headache and primary headache disorder. Secondary headache resulting from other medical conditions, often seen in association with tumors, trauma, bleeding and inflammation, must definitely be considered when warning signs occur. These include, for example, first and sudden occurrences, especially in young children or in patients of advanced age, continuous increase in symptoms or fever, hypertension or seizures as accompanying symptoms. For this purpose, in addition to general physical examinations, laboratory examinations and apparatus examinations can also be carried out. If a secondary cause is excluded, the anamnesis can be used to differentiate between a migraine and other primary forms of headache such as tension headache and cluster headache . For example, an increase in symptoms through physical activity is an important differentiator between a migraine and a cluster headache.

Pathophysiology

Migraine attack

The pathomechanism of the migraine attack is not fully understood. With the help of various complementary hypotheses, an attempt is made to describe the development of a migraine. The neurotransmitters serotonin (5-HT) and glutamate , the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and nitric oxide (NO) play an important role in these theories.

Vascular hypothesis

The vascular hypothesis is based on the classic observation that blood vessels in the head are dilated during a migraine attack. The observed expansion of the blood vessels is considered to be part of a reflex ( trigeminovascular reflex ). In the walls of these blood vessels are pain and stretch receptors (free nerve endings) of the trigeminal nerve , which are activated in the event of a migraine attack. A projection of the stimulation of the trigeminal nerve via stretch receptors or chemoreceptors of the blood vessels in the lower section of the spinal nucleus nervi trigemini and beyond into the cerebral cortex is held responsible for the sensation of pain. A projection into the hypothalamus (photophobia, phonophobia) and into the chemoreceptor trigger zone (nausea, vomiting) is being discussed for the observed accompanying symptoms of migraine .

The pulsating nature of migraine headache can best be explained with the vascular hypothesis. It is also supported by the observation that depending on the predisposition, substances that expand blood vessels ( vasodilators ) such as glycerol trinitrate can trigger a migraine or a migraine-like headache. Mechanical compression of the blood vessels, on the other hand, leads to a reduction in migraine symptoms. The migraine efficacy of all specific migraine therapeutics, including ergot alkaloids , triptans and CGRP receptor antagonists , is at least partially explained by a contraction of the blood vessels in the head. Ergot alkaloids and triptans lead to a direct vascular contraction by activating serotonin receptors of the type 5-HT 1B on the surface of the blood vessels. CGRP antagonists inhibit the vasodilating properties of the calcitonin gene-related peptide through competition at CGRP receptors .

Since the aura symptoms and the accompanying symptoms of the migraine cannot or only insufficiently be explained by the vascular hypothesis, the migraine is no longer regarded as a causal vascular disease today.

Hypothesis of hyperexcitability

The observation that patients who regularly suffer from migraines show an increased excitability of the cerebral cortex of the occipital lobe (occipital cortex) led to the postulation of another hypothesis ( hypothesis of hyperexcitability) . This over-excitability is linked to the release of potassium ions into the extracellular space . Potassium ions cause depolarization that spreads over an area of the cerebral cortex ( scattered polarization or cortical spreading depression). The spread of this depolarization into the visual center is associated with the development of a visual migraine aura. According to this hypothesis, the migraine headache is explained in the simplest case with a projection into certain parts of the so-called sensory trigeminal nucleus. Alternatively, high concentrations of released potassium ions as well as glutamate and nitric oxide can directly trigger a migraine headache.

The striking parallels between the development and spread of a migraine and the pathophysiology of an epileptic seizure are best described by the hypothesis of overexcitability.

Neurogenic Inflammation Hypothesis

The hypothesis of neurogenic inflammation is based on the release of inflammatory messenger substances ( inflammation mediators ) such as calcitonin gene-related peptides (CGRP), substance P and neurokinin A from nerve endings of the fifth cranial nerve ( trigeminal nerve ), which has been proven during a migraine attack . In particular, the CGRP, which can be increasingly detected in the blood plasma during a migraine attack , plays a central role and causes a so-called “sterile neurogenic inflammation” with activation of mast cells . As a result, an expansion of the blood vessels ( vasodilation ), a recruitment of leukocytes and an increase in vascular permeability with the formation of edema can be observed. Activation of matrix metalloproteases can also increase the permeability of the blood-brain barrier for proteins and peptides. Both vasodilation and the increase in permeability with edema formation are discussed as causes of migraine headache.

Genetic causes

Since some forms of migraines occur in families, it can be assumed that genetic defects can play a role in the migraine . In the case of familial hemiplegic migraine, at least three different genetic defects have been identified as possible causes. In type I familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM1), mutations are found in the CACNA1A gene on chromosome 19. This gene encodes a subunit of the voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel . Mutations in the ATP1A2 gene on chromosome 1, which codes for a subunit of sodium-potassium ATPase , an ion pump , are the genetic cause of type II (FHM2). The cause of type III familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM3) is a voltage-dependent sodium channel defect caused by mutations in the SCN1A gene on chromosome 2 . All three described genetic defects are also associated with the occurrence of epilepsy.

For a frequent occurrence of migraine with aura in patients with a persistent foramen ovale , genetic defects are also discussed as the causes of both diseases. Gene defects are also thought to be the cause of comorbidities in migraines and depression .

Treatment and prevention

The German Society for Neurology (DGN) and the German Migraine and Headache Society (DMKG) presented new recommendations for migraine therapy and prophylaxis in May 2018. The S1 guideline therapy of migraine attacks and prophylaxis of migraine is available online.

Migraine is a disease that currently cannot be cured by medical measures. The intensity of the migraine attacks and the frequency of the attacks can be reduced by taking suitable measures.

Acute therapy

According to the recommendation of the German Migraine and Headache Society (DMKG), for the acute treatment of migraine headaches, on the one hand, non-specific pain and inflammation-inhibiting painkillers from the group of non-opioid analgesics ( e.g. acetylsalicylic acid , paracetamol and ibuprofen ) and, on the other hand, specific migraine therapeutics from the groups of Triptans (for example sumatriptan , naratriptan , eletriptan and zolmitriptan ) are used as the first choice.

Non-opioid analgesics

The non-opioid analgesics acetylsalicylic acid, ibuprofen , naproxen , diclofenac and paracetamol are particularly indicated for mild to moderate migraine attacks. A combination of acetylsalicylic acid, paracetamol and caffeine , which is more effective than the individual substances or ibuprofen, is also recommended by the DMKG. Triptans are very effective in moderate to severe attacks . The migraine effectiveness of phenazone and metamizole , however, is considered less well documented. In addition, the COX-2 inhibitors valdecoxib and rofecoxib, which has been withdrawn from the market due to its cardiovascular side effects, have proven effective in the treatment of acute migraine attacks in clinical studies . However, there is no drug approval for use as migraine therapeutics. In general, there is a risk of drug-induced headache with prolonged or even permanent use of non-opioid analgesics .

In order to act quickly and not to aggravate the nausea that often occurs with migraines, many non-opioid analgesics are offered in a dosage form that is quickly available and is considered stomach-friendly. These include, for example, buffered effervescent tablets . Is an oral application of a non-opioid analgesic is not possible, for example, is acetaminophen suppository ( suppository ) for rectal application. Metamizole, acetylsalicylic acid and paracetamol are also available as intravenous infusions.

Triptans

Since the 1990s, there are 5-HT 1B / 1D receptor agonist from the group of triptans for migraine attacks cropping available. Their representatives differ from one another in their pharmacokinetics , especially in their bioavailability , their CNS accessibility and their half-life . In addition, triptans are offered in different dosage forms such as orodispersible tablets , suppositories, nasal sprays and injections for subcutaneous use. Triptans should be taken in good time during a migraine attack (and re-dosed if necessary), otherwise their effectiveness is reduced. With long-term use, however, there is a risk of developing a drug-induced headache. If there is no response to a triptan, another member of this group may still be effective.

Ergot alkaloids

Ergot alkaloids such as ergotamine , which have lost their earlier importance with the introduction of the triptans, can also be used in the acute therapy of migraines. As in the case of the triptans, the migraine effect of the ergot alkaloids is explained by an agonism at the 5-HT 1B / 1D receptor. Its migraine effectiveness has been documented for over a century, but it is difficult to assess due to the extensive lack of modern prospective clinical studies. Compared to triptans, ergot alkaloids are less effective. In addition, they have a much broader spectrum of side effects, including in particular vascular events such as circulatory disorders, but also muscle cramps and drug-induced headaches. Therefore ergot alkaloids are considered to be the second choice, the use of which may be indicated in the case of prolonged migraine attacks and if ergot alkaloids have already been used successfully in the medical history.

Antiemetics

A combination of analgesics or specific migraine therapeutics with an antiemetic or prokinetic such as metoclopramide or domperidone can be useful, as these not only eliminate the gastrointestinal symptoms accompanying migraines (nausea, vomiting), but also promote the absorption of the analgesic. The effectiveness of metoclopramide in this context has been better documented than that of domperidone.

Other therapeutics

Successful therapeutic attempts and indications of effectiveness in smaller clinical studies have also been documented for other therapeutic agents. The anti- epileptic valproic acid has also been shown to be effective against acute migraine attacks . However, valproic acid has not been approved for the acute treatment of migraine under drug law.

Reports of successful acute treatment for otherwise refractory migraines include corticoids such as dexamethasone . Although there is no clear evidence of a direct effect of corticosteroids on migraine pain, they are said to increase the effectiveness of triptans and can also reduce the recurrence rate of migraine attacks.

The opioids established in pain therapy are only considered to be of limited effectiveness in the treatment of migraines. A combination of tramadol and paracetamol was shown in a clinical study to be effective for the treatment of migraine headache, phonophobia and photophobia. However, due to the spectrum of side effects, including nausea and vomiting, which intensify the symptoms of migraines, and the increased risk of drug-induced headache, the application is not recommended.

A 2017 study indicated that cannabis extracts (consisting of the main active ingredients THC and CBD ) could reduce the intensity of pain by around half in acute attacks.

Non-drug methods

Non-drug methods include stimulus shielding through rest in a quiet, darkened room, aromatherapy , peppermint oil rubbing on the forehead, and autogenic training . However, these procedures have not been adequately evaluated.

prophylaxis

The goal of migraine prophylaxis is to reduce the frequency or severity of migraine attacks before they even occur. This is particularly indicated if the patient experiences severe suffering or severe impairment of quality of life from the migraine. A risk-benefit analysis should be carried out. A positive risk-benefit ratio can exist in particular if the patient suffers from migraines particularly frequently (more than three attacks per month), migraine attacks regularly last longer (three days or longer), the migraine cannot be treated satisfactorily with standard therapeutic agents or Difficult-to-treat special forms and complications of migraines are present.

For migraine prophylaxis, drugs are available in particular that were not specifically developed as migraine prophylactic agents, but for various other areas of application, such as the treatment of high blood pressure or epilepsy . A migraine prophylactic effect could subsequently be proven for these drugs.

Beta blockers

Across all guidelines, beta blockers are the first choice for migraine prophylaxis. The prophylactic effect for metoprolol and propranolol is best documented. This effectiveness is directly attributed to an inhibition of β-adrenoceptors of the central nervous system and not, as originally assumed, to an additional inhibition of serotonin receptors mediated by some beta blockers . Thus, effectiveness can also be assumed for other beta blockers. In smaller or older clinical studies, for example, bisoprolol , atenolol or timolol have also proven to be effective migraine prophylactic agents. Beta blockers are particularly indicated if the patient also suffers from high blood pressure, a primary application for beta blockers.

Calcium antagonists

A migraine prophylactic effect of the non-selective calcium antagonist flunarizine is also very well documented. This is why this medicinal product is also classified by international bodies as the first choice. There are no consistent data on migraine prophylactic efficacy for other calcium channel blockers such as verapamil or cyclandelate . A class effect can therefore not be assumed.

Anti-epileptic drugs

Many anti- epileptic drugs are not only able to reduce the frequency of epileptic seizures, but also lead to a decrease in the frequency of migraine attacks. The migraine prophylactic effects of valproic acid and topiramate are best documented of these substances . Taking into account the range of side effects, these substances are also considered to be the first choice if beta blockers cannot be used. The use of valproic acid in migraine prophylaxis corresponds to off-label use in Germany, but not in many other countries , since no preparation containing valproic acid is approved for this indication. Based on data from a single clinical study of gabapentin that showed a slight reduction in the incidence of migraines, it is considered the drug of third choice. For the anti- epileptic lamotrigine, however, no migraine prophylactic effect could be observed, but a reduction in the occurrence of an aura. For other anti-epileptic drugs there is insufficient data on their migraine prophylactic efficacy or, as in the case of oxcarbazepine , they have been shown to be ineffective.

Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP)

CGRP is well characterized as an important factor in the development of migraines. A peripheral release causes severe vasodilation in the body. The peptide is also considered to be a mediator of inflammation. In the central nervous system, CGRP is involved in the regulation of body temperature and modulates the transmission of pain. In May 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a monoclonal antibody ( erenumab / Aimovig , Amgen ) as the first and only FDA-approved method to block the calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor (CGRP-R) .

The monoclonal antibody fremanezumab / Ajovy ( Teva ) was approved for prophylaxis by the FDA in autumn 2018. The European approval authority (EMA) recommended approval for the EU member states at the end of January 2019.

Clinical development

A number of other innovative substances are currently in clinical development (phase III) , e.g. B. for migraine prophylaxis the three monoclonal antibodies eptinezumab (Alder) and galcanezumab ( Lilly ) - and for acute therapy Lasmiditan (Lilly).

Eptinezumab, fremanezumab, and galcanezumab target the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) directly , while erenumab blocks the calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor .

Other therapeutics

The antidepressant amitriptyline has been shown to have a migraine prophylactic effect in a large number of clinical studies. Amitriptyline is therefore classified as the first or second choice in migraine prophylaxis. However, the prophylactic migraine efficacy observed for amitriptyline cannot be transferred to other antidepressants. A study shows that the number of seizures can be reduced with the regular intake of cannabis extract (THC and CBD) as effectively as with amitriptyline.

A migraine prophylactic effect could also be shown for the long-acting non-opioid analgesic naproxen . In contrast, no consistent data on migraine preventive effects are available for other non-opioid analgesics. In addition, there is the risk of developing a drug-induced headache with long-term use. Non-opioid analgesics are therefore considered to be the second or third choice in migraine prophylaxis.

The antihypertensive drugs lisinopril and candesartan , which have been shown to be effective in pilot studies, are considered to be the third choice . Likewise, prophylactic use of botulinum toxin may reduce the frequency of migraine attacks. The value of ergot alkaloids such as dihydroergotamine is controversial despite a drug approval for migraine prophylaxis. The neurokinin receptor antagonist Lanepitant, developed for this indication, has proven to be ineffective . The drugs methysergide and pizotifen , which act by inhibiting serotonin receptors, are, however, effective in migraine prophylaxis. However, due to their severe side effects, they are no longer of therapeutic relevance.

The migraine prophylactic effectiveness of the traditional phytopharmaceutical butterbur has been proven with the help of clinical studies and is classified as the second choice. A marginal effectiveness could also be proven for a CO 2 extract from feverfew. To what extent this effectiveness can be transferred to other extracts is questionable. The possible effectiveness of coenzyme Q 10 , high-dose magnesium (580 mg) and high-dose riboflavin (400 mg) has been less well documented. Homeopathic migraine prophylaxis do not show any effects beyond a placebo effect .

acupuncture

The effectiveness of acupuncture for treating migraines has been examined in numerous studies. In migraine prophylaxis, it is at least as effective as conventional drug prophylaxis with fewer side effects. Acupuncture is therefore often recommended as an additional therapy option. The "correct" placement of the acupuncture needles is irrelevant; a difference between Chinese and non-Chinese or sham points can not be proven .

Other non-drug prophylaxis

The progressive muscle relaxation according to Jacobson and biofeedback may also be an effective way of migraine prophylaxis. In addition, various other methods such as nutritional measures , relaxation techniques, yoga , autogenic training and light endurance sports are available as alternatives. However, their migraine prophylactic effectiveness has not been adequately evaluated.

A randomized clinical trial showed a reduction in monthly headache attacks by supraorbital transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation ( TENS ). This will likely indirectly by repeated electrical stimulation of cutaneous nerves in the central nervous system in the formation of endorphins which pain relieve. However, this has not been proven, which is why TENS is one of the " naturopathic treatments " that are generally not covered by health insurance companies .

The IGeL monitor of the MDS ( Medical Service of the Central Association of Health Insurance Funds ) examined whether migraines occur less often with biofeedback therapy or are less severe . Processes in the body are made perceptible with light or sound signals, for example, in order to be able to control these body processes consciously. After a systematic literature search, the IGeL-Monitor rated the biofeedback therapy as "unclear". Because according to the studies found, it is better to treat migraines with biofeedback than to do nothing. However, a placebo effect cannot be ruled out. When compared to a sham treatment, biofeedback does not show itself to be superior. There is therefore no reliable evidence of a benefit - but also no evidence of possible harm.

Therapy and prophylaxis in pregnancy

The decision to use migraine-effective drugs during pregnancy is based on a risk-benefit assessment that also takes into account possible harm to the unborn child from maternal migraine attacks. Paracetamol is considered tolerable in all phases of pregnancy. In the second trimester , other non-opioid analgesics such as acetylsalicylic acid, ibuprofen and naproxen can also be used. Triptans are not approved for use during pregnancy, but retrospective analyzes do not indicate any harmful effects of sumatriptan, naratriptan and rizatriptan. Ergot alkaloids are contraindicated because of their teratogenic effects . If migraine prophylactic treatment is necessary during pregnancy, apart from non-medicinal procedures such as relaxation exercises, biofeedback and acupuncture, only the beta blocker metoprolol is considered acceptable.

Therapy and prophylaxis in childhood

For the treatment of acute migraine attacks in children, the non-opioid analgesics ibuprofen and paracetamol, possibly supplemented by the use of the prokinetic domperidone , are the first choice. The effectiveness of triptans, however, is not certain. However, recent studies with sumatriptan, zolmitriptan and rizatriptan suggest a migraine-inhibiting effect in children. Triptans are not approved for migraine therapy in children under the age of 12. Alternatively, general measures in the form of stimulus shielding with relaxation in a darkened room, cooling the head and rubbing peppermint oil on the forehead can be undertaken for children.

The effectiveness of flunarizine has been best documented for long-term migraine prophylactic use. Conflicting data exist for propranolol, which is used as a standard prophylactic in adults. For all other drugs used in migraine prophylaxis, there is insufficient knowledge about their effectiveness in children. Relaxation exercises, behavioral therapy measures and biofeedback also show a possible effectiveness, while diet measures were unsuccessful in controlled clinical studies.

Therapy and prophylaxis of the aura

Specific treatment of the migraine aura is usually not necessary. In addition, there are no sufficiently effective drugs available for the acute therapy of the migraine aura. Migraine prophylaxis can be considered if the level of suffering is appropriate. A specific prophylaxis of migrainous aura, but not the headache is for the antiepileptic drug lamotrigine been described.

Comorbidity

People with migraines are at higher risk for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. In a meta-analysis , which included 394,942 patients with migraines and 757,465 comparators without migraines, a stroke risk of 1.42 and a heart attack risk of 1.23 were found. The increase concerned both ischemic (due to vascular occlusion) and haemorrhagic (due to cerebral haemorrhage) strokes. For migraines with aura, the risk of stroke was higher (1.56) than without aura (1.11). The overall risk of death was also higher with aura (1.2) than without aura (0.96).

History of Migraine Therapy

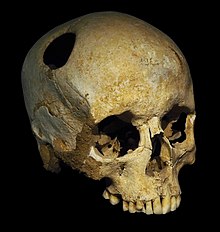

The first attempts at treating migraine headaches can be speculatively traced back to the Mesolithic Age (approx. 8500-7000 BC). During this period, demons and evil spirits in the patient's mind may have been viewed as the cause of migraines and other neurological disorders. Finds from the Neolithic indicate that trepanations (surgical opening of the skullcap) were carried out with the help of stone tools. Although it is controversial whether these treatments were primarily for mystical, cultic or medical reasons, they are said to have been used to let demons escape from the skull. Even if the success rate of the trephination remained undocumented, at least archaeological finds could prove that over 50% of the patients survived this measure. This procedure was used until the 17th century.

Treatment methods for headaches are also documented from ancient Egypt during the time of the pharaohs . This is what he calls from around 1550 BC. Ebers papyrus dated various healing methods for headaches, perhaps migraine headaches, including using the ashes of a catfish skeleton as a rub.

Typical migraine headaches are first described in a text on a Middle Babylonian cuneiform tablet from the library of Tukulti-apil-Ešarra I. (1115-1077 BC).

The famous Greek physician Hippocrates recognized around 400 BC. BC for the first time the aura as a possible harbinger of a headache. He saw the cause as "vapors that rise from the stomach to the head" . The first comprehensive description of the symptoms of a migraine with a unilateral headache as well as sweating, nausea and vomiting was documented by Aretaios in the second century under the name heterocrania . At the same time, he distinguished migraines from other forms of headache. In search of the causes of illness, the theories of Hippocrates were taken up by Galenus , who also further developed his humoral pathology . For the development of hemicrania he made an "excessive, aggressive yellow bile" responsible. The term hemicrania used by him is considered to be the forerunner of today's term "migraine".

A central nervous cause of migraines involving a dilatation of cerebral arteries was first mentioned in 1664 by Thomas Willis . At that time, potassium cyanide , nuke nut , deadly nightshade , foxglove and mercury compounds were used to treat migraines.

Modern migraine therapy was founded in 1884 by William H. Thompson, who recognized an extract from ergot as migraine-effective. In 1920 Arthur Stoll succeeded in isolating the active ingredient ergotamine , which is still used in migraine therapy today. The discovery of the mechanism of action of ergotamine, the stimulation of the serotonin receptors 5-HT 1B / 1D , finally led to the development of modern migraine therapeutics, the triptans group, in the 1980s.

literature

- Hartmut Göbel : Successful against headaches and migraines. 7th edition. Springer, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-642-54725-6 .

- Stefan Evers: Facts. Migraines . Thieme, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-13-143631-X .

- Julia Holzhammer, Christian Wöber: Alimentary trigger factors in migraines and tension-type headaches. In: The pain. 20, 2006, ISSN 0932-433X , pp. 151-159.

- Julia Holzhammer, Christian Wöber: Non-dietary trigger factors in migraines and tension-type headaches. In: The pain. 20, 2006, ISSN 0932-433X , pp. 226-237.

- PJ Goadsby: Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of migraine. In: BMJ. 332 (7532) Jan 7, 2006, pp. 25-29. Review. PMID 16399733 (text is freely accessible).

- Dietrich von Engelhardt: Migraine in medical and cultural history. In: Pharmacy in our time . 31, 5, 2002, ISSN 0048-3664 , pp. 444-451.

- Katrin Janhsen, Wolfgang Hoffmann: Pharmaceutical care for headache patients. In: Pharmacy in our time. 31, 5, 2002, ISSN 0048-3664 , pp. 480-485.

- Günter Neubauer, Raphael Ujlaky: Migraine - a widespread disease and its costs. In: Pharmacy in our time. 31, 5, 2002, ISSN 0048-3664 , pp. 494-497.

- Jan Brand: Migraine - illness or excuse. The hidden illness . Arcis, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-89075-145-8 .

- Oliver Sacks : Migraines . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-499-19963-7 .

- Manfred Wenzel: Migraines. Insel-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 3-458-33389-4 .

Web links

- Pain Clinic Kiel: Migraine Knowledge

- Migraine - Information at Gesundheitsinformation.de (online offer from the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Healthcare )

- S1 guideline therapy of migraine attacks and prophylaxis of migraine of the German Society for Neurology. In: AWMF online (as of 2008)

- S1 guideline for headache caused by overuse of painkillers or migraine drugs of the German Society for Neurology. In: AWMF online (as of May 2018)

- Aspirin with or without an antiemetic for acute migraine headaches in adults. In: V Kirthi, S Derry, RA Moore, HJ McQuay: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 4. Art. No .: CD008041. doi: 10.1002 / 14651858.CD008041.pub2 . Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Group, March 9, 2010, accessed August 19, 2010 .

- German Migraine and Headache Society (DMKG)

- Information from the International Headache Society IHS about migraines

- Migraines in the Open Directory Project

Individual evidence

- ^ Wilhelm Pape , Max Sengebusch (arrangement): Concise dictionary of the Greek language . 3rd edition, 6th impression. Vieweg & Sohn, Braunschweig 1914 ( zeno.org [accessed on September 12, 2019]).

- ^ Friedrich Kluge , Alfred Götze : Etymological dictionary of the German language . 20th edition, ed. by Walther Mitzka . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1967; Reprint (“21st unchanged edition”) ibid 1975, ISBN 3-11-005709-3 , p. 478.

- ↑ a b German Society for Neurology, in charge of HC Diener : S1 guideline therapy for migraine , section epidemiology . In: Guidelines for Diagnostics and Therapy in Neurology. Chapter headaches and other pains. As of September 2012 in the version of March 21, 2013, AWMF registration number 030 - 057

- ↑ M. Obermann, Z. Katsarava: Epidemiology of unilateral headaches. In: Expert Rev Neurother . 8 (9), Sep 2008, pp. 1313-1320. PMID 18759543 .

- ^ LJ Stovner, JA Zwart, K. Hagen, GM Terwindt, J. Pascual: Epidemiology of headache in Europe . In: Eur. J. Neurol. tape 13 , no. 4 , April 2006, p. 333-345 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-1331.2006.01184.x , PMID 16643310 .

- ^ JD Bartleson, FM Cutrer: Migraine update. Diagnosis and treatment . In: Minn Med . tape 93 , no. 5 , May 2010, p. 36-41 , PMID 20572569 .

- ↑ LJ Stovner, K. Hagen, R. Jensen u. a .: The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide . In: Cephalalgia . tape 27 , no. 3 , March 2007, p. 193-210 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x , PMID 17381554 .

- ^ Silvia Romanello: Association Between Childhood Migraine and History of Infantile Colic. In: JAMA. 309, 2013, p. 1607, doi: 10.1001 / jama.2013.747 .

- ↑ a b S.-H. Lee, C. von Stülpnagel, F. Heinen: Therapy of migraine in childhood. Update. In: Monthly Pediatrics. 154, 2006, pp. 764-772.

- ^ WF Stewart, MS Linet, DD Celentano, M. Van Natta, D. Ziegler: Age- and sex-specific incidence rates of migraine with and without visual aura . In: Am. J. Epidemiol. tape 134 , no. November 10 , 1991, pp. 1111-1120 , PMID 1746521 .

- ^ RB Lipton, WF Stewart, DD Celentano, ML Reed: Undiagnosed migraine headaches. A comparison of symptom-based and reported physician diagnosis . In: Arch Intern Med . tape 152 , no. 6 , June 1992, pp. 1273-1278 , PMID 1599358 .

- ↑ G. Neubauer, R. Ujlaky: Migraine - a common disease and its costs . In: Pharm. In our time . tape 31 , no. 5 , 2002, p. 494-497 , doi : 10.1002 / 1615-1003 (200209) 31: 5 <494 :: AID-PAUZ494> 3.0.CO; 2-G , PMID 12369168 .

- ↑ L. Kelman: The premonitory symptoms (prodrome): a tertiary care study of 893 migraineurs . In: Headache . tape 44 , no. 9 , October 2004, p. 865-872 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.2004.04168.x , PMID 15447695 .

- ↑ a b G. G. Schoonman, DJ Evers, GM Terwindt, JG van Dijk, MD Ferrari: The prevalence of premonitory symptoms in migraine: a questionnaire study in 461 patients . In: Cephalalgia . tape 26 , no. 10 , October 2006, p. 1209-1213 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-2982.2006.01195.x , PMID 16961788 .

- ^ J. Todd: The syndrome of Alice in Wonderland . In: Can Med Assoc J . tape 73 , no. 9 November 1955, p. 701-704 , PMID 13304769 , PMC 1826192 (free full text).

- ^ Richard Grossinger: Migraine Auras: When the Visual World Fails . North Atlantic Books, 2006, ISBN 1-55643-619-X , The Nature and Experience of Migraina Auras, pp. 1-96 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j S. Evers, A. May, G. Fritsche, P. Kropp, C. Lampl, V. Limmroth, V. Malzacher, S. Sandor, A. Straube, HC Diener: Acute therapy and prophylaxis of migraine - guidelines of the German Migraine and Headache Society and the German Society for Neurology . In: Neurology . tape 27 , no. 10 , 2008, p. 933-949 ( dmkg.de [PDF]).

- ↑ a b c P. T. Fukui, TR Gonçalves, CG Strabelli et al. a .: Trigger factors in migraine patients . In: Arq Neuropsiquiatr . tape 66 , 3A, September 2008, pp. 494-499 , PMID 18813707 ( scielo.br ).

- ↑ migraines. Retrieved June 30, 2020 .

- ↑ U. Bingel: Migraines and hormones: What is certain? In: pain . 22 Suppl 1, February 2008, p. 31-36 , doi : 10.1007 / s00482-007-0613-9 , PMID 18256855 .

- ^ J. Olesen: The role of nitric oxide (NO) in migraine, tension-type headache and cluster headache . In: Pharmacol Ther . tape 120 , no. 2 , November 2008, p. 157-171 , doi : 10.1016 / j.pharmthera.2008.08.003 , PMID 18789357 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p J. Olesen, GM Bousser, HC Diener u. a .: The international classification of headache disorders - The primary headaches . In: Cephalalgia . tape 24 , Suppl. 1, 2004, p. 24-136 .

- ↑ Headache Classification in Medical History. Stefan Evers. Neurology 2019; 38; 714-721

- ^ Website The International Headache Classification (ICHD-3 Beta) . Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ↑ A. May: Diagnostics and modern therapy of migraine. In: Dtsch. Doctor bl. 103 (17), 2003, p. A 1157-A 1166.

- ↑ J. Olesen, GM Bousser, HC Diener u. a .: The international classification of headache disorders - Appendix . In: Cephalalgia . tape 24 , Suppl. 1, 2004, p. 138-149 .

- ↑ a b A. H. Stam, AM van den Maagdenberg, J. Haan, GM Terwindt, MD Ferrari: Genetics of migraine: an update with special attention to genetic comorbidity . In: Curr. Opin. Neurol. tape 21 , no. 3 , June 2008, p. 288-293 , doi : 10.1097 / WCO.0b013e3282fd171a , PMID 18451712 ( wkhealth.com ).

- ^ Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition . In: Cephalalgia . tape 38 , no. 1 , January 2018, p. 1-211 , doi : 10.1177 / 0333102417738202 .

- ^ A b J. R. Graham, HG Wolff: Mechanism of migraine headache and action of ergotamine tartrate . In: Arch Neurol Psychiatry . tape 39 , 1938, pp. 737-763 .

- ^ A. May, PJ Goadsby: The trigeminovascular system in humans: pathophysiologic implications for primary headache syndromes of the neural influences on the cerebral circulation . In: J. Cereb. Blood flow metab. tape 19 , no. 2 , February 1999, p. 115-127 , doi : 10.1097 / 00004647-199902000-00001 , PMID 10027765 .

- ↑ LL Thomsen, J. Olesen: Nitric oxide theory of migraine . In: Clin. Neurosci. tape 5 , no. 1 , 1998, p. 28-33 , PMID 9523055 .

- ↑ MA Moskowitz, K. Nozaki, RP Kraig: Neocortical spreading depression provokes the expression of c-fos protein-like immunoreactivity within trigeminal nucleus caudalis via trigeminovascular mechanisms . In: J. Neurosci. tape 13 , no. 3 , March 1993, p. 1167-1177 , PMID 8382735 .

- ↑ MA Moskowitz: Neurogenic inflammation in the pathophysiology and treatment of migraine . In: Neurology . tape 43 , 6 Suppl 3, June 1993, pp. S16-S20 , PMID 8389008 .

- ↑ PJ Goadsby, L. Edvinsson, R. Ekman: Vasoactive peptide release in the extracerebral circulation of humans during migraine headache . In: Ann. Neurol. tape 28 , no. 2 , August 1990, p. 183-187 , doi : 10.1002 / ana.410280213 .

- ↑ P Geppetti, JG Capone, M. Trevisani, P. Nicoletti, G. Zagli, MR Tola: CGRP and migraine: neurogenic inflammation revisited . In: J Headache Pain . tape 6 , no. 2 , April 2005, p. 61-70 , doi : 10.1007 / s10194-005-0153-6 , PMID 16362644 .

- ↑ Y. Gursoy-Ozdemir, J. Qiu, N. Matsuoka et al. a .: Cortical spreading depression activates and upregulates MMP-9 . In: J. Clin. Invest. tape 113 , no. 10 , May 2004, pp. 1447-1455 , doi : 10.1172 / JCI21227 , PMID 15146242 , PMC 406541 (free full text).

- ↑ nature.com

- ↑ nature.com

- ↑ J. Haan, AM van den Maagdenberg, OF Brouwer, MD Ferrari: Migraine and epilepsy: genetically linked? In: Expert Rev Neurother . tape 8 , no. 9 , September 2008, p. 1307-11 , doi : 10.1586 / 14737175.8.9.1307 , PMID 18759542 .

- ↑ HC Diener, M. Küper, T. Kurth: Migraine-associated risks and comorbidity . In: J. Neurol. tape 255 , no. 9 , September 2008, p. 1290-1301 , doi : 10.1007 / s00415-008-0984-6 , PMID 18958572 .

- ↑ Guideline of the German Society for Neurology (DGN) in cooperation with the German Migraine and Headache Society (DMKG) , DGN website, accessed on June 25, 2018

- ↑ HC Diener, V. Pfaffenrath, L. Pageler, H. Peil, B. Aicher: The fixed combination of acetylsalicylic acid, paracetamol and caffeine is more effective than single substances and dual combination for the treatment of headache: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, single-dose, placebo-controlled parallel group study . In: Cephalalgia . tape 25 , no. 10 , October 2005, p. 776-787 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-2982.2005.00948.x , PMID 16162254 .

- ↑ J. Goldstein et al. a .: Acetaminophen, aspirin, and caffeine in combination versus ibuprofen for acute migraine: results from a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, single-dose, placebo-controlled study. In: Headache. 46, 2006, pp. 444-453. PMID 16618262

- ↑ Hartmut Göbel Pain Clinic Kiel: Mirgänewissen - Seizure Treatment

- ↑ D. Kudrow, HM Thomas, G. Ruoff and a .: Valdecoxib for treatment of a single, acute, moderate to severe migraine headache . In: Headache . tape 45 , no. 9 , October 2005, p. 1151-1162 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.2005.00238.x , PMID 16178945 .

- ^ S. Silberstein, S. Tepper, J. Brandes u. a .: Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of rofecoxib in the acute treatment of migraine . In: Neurology . tape 62 , no. 9 , May 2004, p. 1552-1557 , PMID 15136680 .

- ^ Pain Clinic Kiel: Migraine Knowledge - Seizure Treatment

- ↑ P. Tfelt-Hansen, PR Saxena, C. Dahlöf a. a .: Ergotamine in the acute treatment of migraine: a review and European consensus . In: Brain . 123 (Pt 1), January 2000, p. 9-18 , PMID 10611116 .

- ↑ HC Diener, JP Jansen, A. Reches, J. Pascual, D. Pitei, TJ Steiner: Efficacy, tolerability and safety of oral eletriptan and ergotamine plus caffeine (Cafergot) in the acute treatment of migraine: a multicentre, randomized, double -blind, placebo-controlled comparison . In: Eur. Neurol. tape 47 , no. 2 , 2002, p. 99-107 , PMID 11844898 ( karger.com ).

- ^ KR Edwards, J. Norton, M. Behnke: Comparison of intravenous valproate versus intramuscular dihydroergotamine and metoclopramide for acute treatment of migraine headache . In: Headache . tape 41 , no. 10 , 2001, p. 976-980 , doi : 10.1046 / j.1526-4610.2001.01191.x , PMID 11903525 .

- ↑ T. Leniger, L. Pageler, P. Stude, HC Diener, V. Limmroth: Comparison of intravenous valproate with intravenous lysine-acetylsalicylic acid in acute migraine attacks . In: Headache . tape 45 , no. 1 , January 2005, p. 42-46 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.2005.05009.x , PMID 15663612 .

- ↑ M. Bigal, F. Sheftell, S. Tepper, D. Tepper, TW Ho, A. Rapoport: A randomized double-blind study comparing rizatriptan, dexamethasone, and the combination of both in the acute treatment of menstrually related migraine . In: Headache . tape 48 , no. 9 , October 2008, p. 1286-1293 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.2008.01092.x , PMID 19031496 .

- ^ I. Colman, BW Friedman, MD Brown et al. a .: Parenteral dexamethasone for acute severe migraine headache: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials for preventing recurrence . In: BMJ . tape 336 , no. 7657 , June 2008, p. 1359-1361 , doi : 10.1136 / bmj.39566.806725.BE , PMID 18541610 , PMC 2427093 (free full text).

- ^ SD Silberstein, FG Friday, TD Rozen u. a .: Tramadol / acetaminophen for the treatment of acute migraine pain: findings of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial . In: Headache . tape 45 , no. 10 , 2005, pp. 1317-1327 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.2005.00264.x , PMID 16324164 .

- ↑ a b Interactive Program Planner - EAN Congress 2017 in Amsterdam. (No longer available online.) Formerly in the original ; accessed on November 30, 2017 (English). ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ KG Shields, PJ Goadsby: Propranolol modulates trigeminovascular responses in thalamic ventroposteromedial nucleus: a role in migraine? In: Brain . tape 128 , Pt 1, January 2005, p. 86-97 , doi : 10.1093 / brain / awh298 , PMID 15574468 .

- ↑ H. Nishio, Y. Nagakura, T. Segawa: Interactions of carteolol and other beta-adrenoceptor blocking agents with serotonin receptor subtypes . In: Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther . tape 302 , 1989, pp. 96-106 , PMID 2576893 .

- ^ R. Wörz, B. Reinhardt-Benmalek, KH Grotemeyer: Bisoprolol and metoprolol in the prophylactic treatment of migraine with and without aura - a randomized double-blind cross-over multicenter study . In: Cephalalgia . tape 11 , Suppl. 11, 1991, pp. 152-153 .

- ^ V. Johannsson, LR Nilsson, T. Widelius u. a .: Atenolol in migraine prophylaxis a double-blind cross-over multicentre study . In: Headache . tape 27 , no. 7 , July 1987, pp. 372-374 , PMID 3308768 .

- ^ RM Gallagher, RA Stagliano, C. Sporazza: Timolol maleate, a beta blocker, in the treatment of common migraine headache . In: Headache . tape 27 , no. 2 , February 1987, p. 84-86 , PMID 3553070 .

- ↑ a b c S. D. Silberstein: Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology . In: Neurology . tape 55 , no. 6 , September 2000, p. 754-762 , PMID 10993991 .

- ↑ a b c d e S. Evers, J. Afra, A. Frese u. a .: EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine - report of an EFNS task force . In: Eur. J. Neurol. tape 13 , no. 6 , June 2006, p. 560-572 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-1331.2006.01411.x , PMID 16796580 .

- ^ NT Mathew, A. Rapoport, J. Saper et al. a .: Efficacy of gabapentin in migraine prophylaxis . In: Headache . tape 41 , no. 2 , February 2001, p. 119-128 , doi : 10.1046 / j.1526-4610.2001.111006119.x , PMID 11251695 .

- ↑ a b J. Pascual, AB Caminero, V. Mateos u. a .: Preventing disturbing migraine aura with lamotrigine: an open study . In: Headache . tape 44 , no. 10 , 2004, p. 1024-1028 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.2004.04198.x , PMID 15546267 .

- ^ S. Silberstein, J. Saper, F. Berenson, M. Somogyi, K. McCague, J. D'Souza: Oxcarbazepine in migraine headache: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study . In: Neurology . tape 70 , no. 7 , February 2008, p. 548-555 , doi : 10.1212 / 01.wnl.0000297551.27191.70 , PMID 18268247 .

- ↑ Monoclonal antibodies for the prophylaxis of migraines - erenumab (Aimovig®), galcanezumab (Emgality®) and fremanezumab (Ajovy®) - change if you do not respond? , Drug Ordinance in Practice, AKDAE of January 30, 2020, accessed on January 31, 2020

- ↑ FDA approves novel preventive treatment for migraine , PM FDA, May 17, 2018, accessed May 20, 2018

- ↑ FDA Approves Aimovig ™ (erenumab-aooe), A Novel Treatment Developed Specifically For Migraine Prevention , PM Amgen, May 17, 2018, accessed May 19, 2018

- ↑ Aimovig ( Memento of the original from May 18, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Multimedia News Release, accessed May 19, 2018

- ↑ Migraine antibody fremanezumab now receives US approval , Deutsche Apotheker Zeitung of September 18, 2018, accessed on February 1, 2019

- ^ Otsuka and Teva Sign Licensing Agreement for Japan on Prophylactic Migraine Drug Candidate Fremanezumab (TEV-48125) . PM Teva on May 15, 2017, accessed June 11, 2017.

- ↑ Meeting highlights from the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) 28-31 January 2019 . PM EMA dated February 1, 2019, accessed February 1, 2019

- ↑ Migraines: New Antibodies for Prevention. In: Pharmaceutical newspaper online. Avoxa Mediengruppe Deutscher Apotheker GmbH, accessed on October 28, 2017 .

- ↑ Lilly to Present Late-Breaking Data for Galcanezumab and Lasmiditan at the American Headache Society Annual Scientific Meeting ( Memento of the original from August 10, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , PM Lilly on June 8, 2017, accessed June 9, 2017.

- ↑ Lilly's Galcanezumab Significantly Reduces Number of Migraine Headache Days for Patients with Migraine: New Results Presented at AHS . ( Memento of the original from June 27, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. PM Lilly on June 10, 2017, accessed June 11, 2017.

- ↑ Lilly Announces Positive Results for Second Phase 3 Study of Lasmiditan for the Acute Treatment of Migraine . ( Memento of the original from August 5, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. PM Lilly, August 4, 2017, accessed August 10, 2017.

- ↑ KM Welch, DJ Ellis, PA Keenan: Successful migraine prophylaxis with naproxen sodium . In: Neurology . tape 35 , no. 9 , September 1985, pp. 1304-1310 , PMID 4022376 .

- ↑ DJ Goldstein, WW Offen, EG Klein u. a .: Lanepitant, an NK-1 antagonist, in migraine prevention . In: Cephalalgia . tape 21 , no. 2 , March 2001, p. 102-106 , doi : 10.1046 / j.1468-2982.2001.00161.x , PMID 11422091 .

- ^ HC Diener, VW Rahlfs, U. Danesch: The first placebo-controlled trial of a special butterbur root extract for the prevention of migraine: reanalysis of efficacy criteria . In: Eur. Neurol. tape 51 , no. 2 , 2004, p. 89-97 , doi : 10.1159 / 000076535 , PMID 14752215 ( karger.com ).

- ↑ RB Lipton, H. Göbel, KM Einhäupl, K. Wilks, A. Mauskop: Petasites hybridus root (butterbur) is an effective preventive treatment for migraine . In: Neurology . tape 63 , no. December 12 , 2004, pp. 2240-2244 , PMID 15623680 .

- ↑ MH Pittler, E. Ernst: Feverfew for preventing migraine. In: Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2004, CD002286.

- ↑ H. Walach, W. Haeusler, T. Lowes a. a .: Classical homeopathic treatment of chronic headaches . In: Cephalalgia . tape 17 , no. 2 , April 1997, p. 119-126; discussion 101 , doi : 10.1046 / j.1468-2982.1997.1702119.x , PMID 9137850 .

- ↑ TE Whitmarsh, DM Coleston-Shields, TJ Steiner: Double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study of homoeopathic prophylaxis of migraine . In: Cephalalgia . tape 17 , no. 5 , August 1997, p. 600-604 , doi : 10.1046 / j.1468-2982.1997.1705600.x , PMID 9251877 .

- ↑ K. Linde, G. Allais, B. Brinkhaus, E. Manheimer, A. Vickers, AR White: Acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis . In: Cochrane Database Syst Rev . No. 1 , 2009, p. CD001218 ( cochrane.org ).

- ↑ DB Penzien, F. Andrasik, BM Freidenberg u. a .: Guidelines for trials of behavioral treatments for recurrent headache, first edition: American Headache Society Behavioral Clinical Trials Workgroup . In: Headache . 45 Suppl 2, May 2005, p. S110 – S132 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1526-4610.2005.4502004.x , PMID 15921503 .

- ^ Y. Nestoriuc, A. Martin: Efficacy of biofeedback for migraine: a meta-analysis . In: Pain . tape 128 , no. 1-2 , March 2007, pp. 111-127 , doi : 10.1016 / j.pain.2006.09.007 , PMID 17084028 .

- ↑ J. Schoenen, B. Vandersmissen, S. Jeangette, L. Herroelen, M. Vandenheede, P. Gérard, D. Magis: Migraine prevention with a supraorbital transcutaneous stimulator: a randomized controlled trial. In: Neurology . tape 80 , no. 8 , February 2013, p. 697-704 , doi : 10.1212 / WNL.0b013e3182825055 , PMID 23390177 .

- ↑ IGeL-Monitor: Biofeedback for migraines . accessed on January 14, 2019. More on the justification for the assessment in the results report . (PDF) accessed on January 14, 2019.

- ↑ L. Damen, JK Bruijn, AP Verhagen, MY Berger, J. Passchier, BW Koes: Symptomatic treatment of migraine in children: a systematic review of medication trials . In: Pediatrics . tape 116 , no. 2 , August 2005, p. e295 – e302 , doi : 10.1542 / peds.2004-2742 , PMID 16061583 .

- ↑ K. Ahonen, ML Hämäläinen, M. Eerola, K. Hoppu: A randomized trial of rizatriptan in migraine attacks in children . In: Neurology . tape 67 , no. 7 , October 2006, p. 1135-1140 , doi : 10.1212 / 01.wnl.0000238179.79888.44 , PMID 16943370 .

- ^ DW Lewis, P. Winner, AD Hershey, WW Wasiewski: Efficacy of zolmitriptan nasal spray in adolescent migraine . In: Pediatrics . tape 120 , no. 2 , August 2007, p. 390-396 , doi : 10.1542 / peds.2007-0085 , PMID 17671066 .

- ↑ L. Damen, J. Bruijn, AP Verhagen, MY Berger, J. Passchier, BW Koes: Prophylactic treatment of migraine in children. Part 2. A systematic review of pharmacological trials . In: Cephalalgia . tape 26 , no. 5 , May 2006, pp. 497-505 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-2982.2005.01047.x , PMID 16674757 .

- ^ L. Damen, J. Bruijn, BW Koes, MY Berger, J. Passchier, AP Verhagen: Prophylactic treatment of migraine in children. Part 1. A systematic review of non-pharmacological trials . In: Cephalalgia . tape 26 , no. 4 , April 2006, p. 373-383 , doi : 10.1111 / j.1468-2982.2005.01046.x , PMID 16556238 .

- ↑ Ahmed N Mahmoud, Amgad Mentias, Akram Y Elgendy, Abdul Qazi, Amr F Barakat: Migraine and the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events: a meta-analysis of 16 cohort studies including 1 152 407 subjects . In: BMJ Open . tape 8 , no. 3 , 2018, ISSN 2044-6055 , p. e020498 , doi : 10.1136 / bmjopen-2017-020498 , PMID 29593023 , PMC 5875642 (free full text) - ( bmj.com [accessed November 24, 2019]).

- ^ A b Carlos M. Villalón u. a .: An Introduction to Migraine: from Ancient Treatment to Functional Pharmacology and Antimigraine Therapy. In: Proc. West. Pharmacol. Soc. 45, 2002, pp. 199-210.

- ↑ a b c Christian Waeber, Michael A. Moskowitz: Therapeutic implications of central and peripheral neuroligic mechanisms in migraine. In: Neurology. 61 (Suppl. 4), 2003, pp. S9-S20.

- ^ Manfred Wenzel: Migraine. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 987.

- ↑ Hartmut Göbel: The headache . 2nd Edition. Springer, 2004, ISBN 3-540-03080-8 , Migraine, pp. 141-368 .