Niuserre

| Name of Niuserre | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Double statue of Niuserre; State Museum of Egyptian Art , Munich

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Horus name |

S.t-jb-t3.wj seat of the heart of the two countries |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sideline |

S.t-jb-nb.tj seat of the heart of the two mistresses |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gold name |

Bjk-nbw-nṯr.j Gold (Golden) of the Divine Falcon |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Throne name |

N (.j) -wsr-R to strength / power of Re duly |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

Jnj Ini

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| List of Kings of Abydos (Seti I) (No. 30) |

N (.i) -wsr-Rˁ Belongs to the strength / power of Re |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Greek for Manetho |

Rathures |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Niuserre ( Ni-user-Re , also Niuserre Ini ) was the sixth king ( pharaoh ) of the ancient Egyptian 5th dynasty in the Old Kingdom . He ruled approximately within the period from 2455 to 2420 BC. The exact length of his reign is unclear, but the majority of researchers assume about 30 years or more. The royal necropolis of Abusir is strongly influenced by its extensive construction projects. This includes the construction of his pyramid complex and a solar sanctuary , but also the completion of the tombs of his father, his brother and his mother. Hardly any concrete events from Niuserre's reign have come down to us. Administrative reforms led to the bundling of various departments in the hands of the vizier , the highest official in Egypt. Expeditions to Wadi Maghara on the Sinai and to Nubia are attested by inscriptions, and by archaeological finds there are also trade connections to Byblos . The cult of the dead established for Niuserre and the worship associated with it lasted into the Middle Kingdom .

Origin and family

Niuserre was a son of King Neferirkare and his wife Chentkaus II. His brother was given the birth name Ranefer and after the death of his father ascended the throne under the name Raneferef , but died after only a few years. The Royal Wife Niuserres was Reputnebu . The only known child from this marriage was the daughter Chamerernebti , who was married to the vizier Ptahschepses and had five children with him. So far, the ruler's family relationship with Schepseskare , who ruled shortly after Raneferef's death, and with Menkauhor , Niuserre's immediate successor, is completely unclear .

Domination

Term of office

A reliable estimate of the duration of Niuserre's government is difficult. In the royal papyrus of Turin , which dates from the 19th dynasty , the ruler's name has been lost and the name of his reigning years has been severely damaged. The entry was probably "11 (+ x?) Years". In the 3rd century BC Living Egyptian priests Manetho names 44 years, which is generally considered to be too high in research. The contemporary sources do not provide a clear picture. On the one hand, the inscribed dates seem to speak for a rather short reign. The highest recorded date is a "seventh time of the count". This refers to a cattle count that originally took place every two years, but which has also been carried out annually at the latest since the beginning of the 4th dynasty. Since the well-known date inscriptions from Niuserre's reign refer to four “years of counting” but only to one “year after the counting”, a period of reign that roughly coincides with the assumed eleven years of the Turin papyrus is therefore entirely plausible. On the other hand, there are pictorial representations in the solar sanctuary of Niuserre, which show the king at the Sed festival . This festival ideally took place only after 30 years of government, but could in principle also be held earlier. Some inscriptions from the mastaba of Ptahschepses in Abusir are only sufficient to determine an approximate minimum duration of Niuserre's rule, but not a maximum duration. The mastaba was erected in three phases, with construction beginning around the fifth "year of the count". From the second construction phase onwards, Niuserre's daughter Chamerernebti was named in the inscriptions as Ptahschepses' wife. Two building inscriptions from a Raneferefanch date from the same construction phase. Due to his name, he was born during the reign of Raneferef at the earliest and must have been a grown man when the inscriptions were affixed. Since the reigns of Raneferef, who died young, and his successor Schepseskare, together, should not have exceeded three to four years, the minimum duration for Niuserre's rule is well over ten years.

Circumstances of the seizure of power

So far, the question of why Niuserre did not ascend the throne immediately after the death of his brother Raneferef, but why a ruler named Schepseskare ruled between the two for a short time has not yet been clarified. Miroslav Verner set up several hypothetical scenarios for this, based on disputes over the throne within the royal family. According to this, Schepseskare could have been a son of Sahure and thus an uncle of Niuserre, who was able to briefly enforce his claims to power against the still young crown prince (for a detailed description see Schepseskare ).

State administration

Under Niuserre there was a strong centralization of various administrative departments in the hands of the highest official, the vizier , whose office was thereby considerably strengthened. The offices of the “ Head of the Two Treasure Houses ”, the “Head of the Two Barns” and the “Head of the Two Chamber of the King's Treasures” (i.e. the head of the royal jewelry) now became an integral part of the vizier's office. Thus the responsibility for all material matters of the residence was bundled in one office. The connection between two further, newly created offices with the vizier can be seen from the title of an official named Kai . He had initially worked as the “head of the big house”, a legal institution, and after his appointment as a vizier as “head of the 6 big houses” he also became the supervisor of all legal affairs in the country. As “Head of Upper Egypt”, he was finally given responsibility for the provincial administration.

Besides Kai, Minnefer and Ptahschepses were certainly acting viziers under Niuserre. Sechemanchptah may also be classified under his rule. Other officials who can certainly be dated to his reign are the two “chiefs of all the king's work” Anchuserkaf and Seschemnefer (II.) . Ptahschepses occupies the most prominent position among all officials, which is made clear by his marriage to the princess Chamerernebti and the construction of the largest private grave of the Old Kingdom.

Trade relations and expeditions

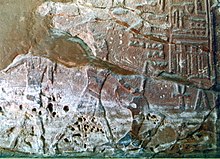

Two rock reliefs that were discovered in the Wadi Maghara on Sinai date from the time of Niuserre . One of them is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo . The inscription names the beating of the Mentiu and all foreign countries . The reliefs suggest a royal expedition into the copper and turquoise mines of the wadi, but not necessarily a real military conflict. Recently found seal impressions and a rock inscription prove that the starting point for Niuserre's activities on the Sinai peninsula was the port of Ain Suchna on the Gulf of Suez .

Trade relations with the Levant are documented by a statue of Niuserre found in Byblos (see below) and by a fragment of travertine vessel with his name that was found at the same place. Activities in Nubia are evidenced by a seal that was found in the Buhen fortress on the 2nd Nile cataract , as well as fragments of a stele with Niuserre's name, which comes from the sub-Nubian gneiss quarry near Gebel el-Asr .

Other documents from Niuserre's reign

In the temple of Satis on Elephantine one was Fayencetafel with Niuserres name found. However, since neither these nor comparable pieces were found in their original context, but in landfills, their exact purpose is unclear. It could be used as an insert between wall tiles, but also as a foundation addition.

Construction activity

The well-known construction activity of Niuserre was limited to Abusir, but had a lasting impact on the necropolis there, as no ruler before him had such extensive construction work carried out there. After both his father and brother died after a relatively short reign, Niuserre was initially confronted with several unfinished projects that had to be completed. These were the tombs of Neferirkares and Raneferefs, but also those of his mother Chentkaus II. The topographical conditions in Abusir led to some unusual decisions when building his own pyramid. As the only economically sensible building site, there was only one place very close to his father's pyramid. Obviously due to lack of space he could not build the pyramids of his queens here, but had to move them to the southern end of the necropolis, near the tombs of his brother and his mother. Another building project in Niuserre was the construction of a solar sanctuary at Abu Gurob in the far north of Abusir. After Niuserre's death, Abusir lost its importance as a royal necropolis. He was the last ruler to have his own tomb built here. His successor Menkauhor went to Sakkara and Djedkare only had a few graves built for family members in Abusir.

Completion of the construction projects of its predecessors

The Neferirkare pyramid

With a base dimension of 105 m and a desired height of 72 m, Neferirkare had planned a grave complex that was to be significantly larger than that of his predecessors. While the actual pyramid was largely completed during his lifetime, most of the cladding and probably the entire temple complex were still missing when he died. Under Raneferef, work on the disguise appears to have continued. A first limestone mortuary temple was also built on the east side of the pyramid.

After his accession to the throne, Niuserre gave up the work on the cladding and concentrated entirely on the mortuary temple, which he significantly expanded in brick construction. This part no longer received a stone foundation, but with the help of filled brick chambers, a level base area, which was then covered with a clay floor. The outer part of the temple consists of a columned portico , a slightly sloping columned hall and a courtyard surrounded by columns. The temple and pyramid are surrounded by a brick wall. An access road and a valley temple do not seem to have been planned by Niuserre. Nor did he have a cult pyramid built for Neferirkare . Instead, he had priestly quarters built in the place where such a structure is usually found in other pyramid complexes (i.e. south of the inner limestone temple), in which an archive was discovered that contained the important Abusir papyri .

The Chentkaus II pyramid

With the death of Neferirkare, the work on the pyramid of his wife Chentkaus II was interrupted for the time being. It is known through building graffiti that the construction was carried out in the 10th or 11th year of the ruler's reign, up to about the height of the burial chamber ceiling. Since during the short reigns of Raneferef and Schepseskare hardly any noteworthy expansions were likely to have taken place, it was finally only completed under Niuserre. The pyramid, built from construction waste, was clad in fine, white limestone and was given a mortuary temple on its east side, which was built in two phases: The first temple was built from limestone and had a pillar courtyard, a hall for the cult statues of the queen, and an offering hall and magazine rooms. In a second phase, the brick building was expanded to the south and east. A new entrance area, additional storage rooms and a priest's quarters were added. A small cult pyramid was built southeast of the limestone temple, which is an innovation, as previously only king pyramids had their own cult pyramid. The entire complex was surrounded with a wall and thus clearly separated from the pyramid complex of the Neferirkare.

The Raneferef pyramid

When Raneferef died after only a short reign, only a stump of his pyramid with a height of 7 m was completed. The original plans were then abandoned and the construction that had begun was converted into a flat mastaba . Probably under Schepseskare, a first small mortuary temple made of limestone was built on the east side of the complex. After Niuserre came to power, the temple complex was extensively expanded using brick construction. Storage rooms were built to the north and east of the small limestone temple, and to the south a hall with a star-studded ceiling supported by wooden lotus pillars. The entire complex was enclosed by a wall, on the eastern outer side of which a "knife sanctuary" was built, a slaughterhouse serving the cult of the dead. Niuserre had this original design changed again in a later construction phase and thus resembled the rather unusual building more to the typical T-shaped mortuary temple floor plan of the 5th dynasty. A courtyard surrounded by 22 wooden columns, an entrance hall and an entrance flanked by two limestone papyrus columns were added to the east. A valley temple and an access path, which would actually have completed the pyramid complex, were not built.

Own construction projects

The Niuserre pyramid in Abusir

For his own pyramid complex called Mn-swt-Nj-wsr-Rˁ (Men-sut-Ni-user-Re, The sites of Niuserre exist ), Niuserre chose a location between the pyramids of his father Neferirkare and his grandfather Sahure. With a base size of 78.50 m, it has the same dimensions as the tomb of the Sahure. The core masonry is made of limestone and forms seven steps, which were covered by a cladding of finer, white limestone. The entrance to the chamber system is on the north side of the pyramid. From there an irregular corridor leads to an antechamber. Halfway down the aisle there is a blocking device with two granite stones. The entrance to the burial chamber is on the west side of the antechamber. Both rooms have a mighty gable roof made of three layers of large limestone blocks. Due to massive stone robberies, an exact reconstruction of the original appearance of the vestibule and burial chamber is hardly possible today. No remains of the burial or grave goods were found either.

The mortuary temple of the Niuserre pyramid has some special features. The most striking of these is that its eastern part is shifted to the south and the temple has an L-shaped floor plan instead of the usual T-shaped one. This eastern part houses an entrance hall flanked by storage rooms and a courtyard surrounded by columns. A transverse corridor separates the eastern, public part of the temple from the western, reserved for cult. The remains of a lion statue were discovered in a niche in the corridor. An important architectural innovation is an antichambre carée (German roughly "square antechamber"), a square room with a column in the middle, which is in front of the sacrificial hall and from now on remained an integral part of all royal mortuary temples until the Middle Kingdom . A small cult pyramid was erected at the southeast corner of the royal pyramid. The entire complex was surrounded with a wall, which has massive corner buildings in the southeast and northeast, which are regarded as forerunners of pylons .

The valley temple on the edge of the fruiting land was originally started for Neferirkare, but was never completed. Niuserre therefore took over the foundations for the valley temple and the pathway , which does not run straight to the pyramid, as it had to be diverted to his tomb when building his facility . The valley temple has two entrances: one from the east, where the port facility was once located, and another to the west. The center of the temple is a room with several statue niches, which presumably originally contained cult images of the king, but next to it the head of a statue of his wife Reputnebu and remains of figures of defeated enemies were found.

The queen pyramid Lepsius XXIV

To the south of the Chentkaus II pyramid, Niuserre built a queens pyramid, which can be clearly dated to his reign thanks to building graffiti. The building was badly damaged by stone robbery. It has a base dimension of 31.5 m and an original height of 27.3 m, but now only rises 5 m. The chamber system consists of a corridor leading down from the north side and a centrally located burial chamber. In addition to the remains of the grave equipment, the mummy of a young woman between the ages of 21-23 was found there. Due to the lack of inscriptions, her identity is unclear, but it seems likely that it is the original owner of the grave, in whom a wife of Niuserre can be seen. On the east side of the pyramid, the remains of a small cult pyramid and the mortuary temple have been preserved. Both are badly affected by stone robbery. A reconstruction of the original temple plan is therefore no longer possible.

The "twin pyramid" Lepsius XXV

Only a few meters south of the Lepsius XXIV pyramid is a building that is so far unique for the Egyptian pyramid construction, as two pyramids were apparently built directly next to each other. The eastern one has a base size of 27.70 m × 21.53 m and today still reaches a height of 6 m. The core masonry consists of different materials, a cladding never seems to have been attached. From the north, a passage initially leads down at an angle, then runs horizontally and finally opens into the burial chamber. The remains of a female burial and grave equipment were found there. The only sacrificial area was a small limestone room on the east side of the pyramid. A female statuette and a papyrus fragment were found here.

With a base size of 21.70 m × 15.70 m, the western pyramid is slightly smaller than the eastern one. It also has a higher degree of destruction. Only parts of the foundations of the original chamber system have survived, so that its dimensions can no longer be precisely determined. Here, too, only a few remains of the burial and grave goods have survived. A separate victim area for the western facility could not be proven.

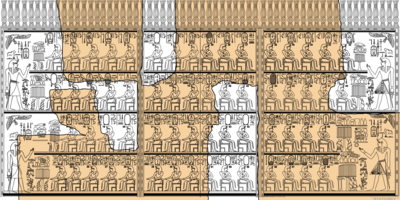

The solar sanctuary of Niuserre in Abu Gurob

The second central building project Niuserre represented his solar sanctuary with the name Šsp-jb-Rˁ (Schesep-ib-Re, pleasure place of the Re ). It is located near Abu Gurob, only a few hundred meters north of the solar sanctuary of Userkaf and is the only one next to it preserved of the six known solar sanctuaries of the 5th Dynasty. Similar to a pyramid complex, it has a valley temple on the edge of the fruit land, from which a steep path leads to a hill, which is horizontally extended by artificial terraces, on which the actual sanctuary is located. This is surrounded by a rectangular wall. The entrance hall is on the east side. This is followed by an open courtyard with an altar in the center. The western part of the sanctuary is occupied by a mighty, brick obelisk . A decorated corridor runs along the southern perimeter wall. Storage rooms are built on the northern one, as well as two other buildings, which are referred to as "slaughterhouses" in research history, but which probably never served as such. Outside the actual temple, on its southeast corner, is a large model of a sun ship made of wood and adobe. Significant reliefs were found in the sun sanctuary. These include scenes from the southern corridor and an adjoining chapel that show Niuserre at the Sed festival. Representations from the so-called World Chamber next to the substructure of the obelisk are just as important: there, human activities and events in nature over the course of the seasons are depicted in great detail.

Statues

With inscriptions and stylistic comparisons, six sculptures can be assigned to the ruler. A pseudo-group that is now in the State Museum of Egyptian Art in Munich (Inv.-No. ÄS 6794) occupies a prominent position . It is the only known royal example of this type of statue from the Old Kingdom. The piece is of unknown origin and is made of calcite . It is 71.8 cm high and 40.8 cm wide. Inscriptions on the statue base mention the name Niuserres. The king is standing almost identically twice, with his left foot forward, shown side by side. The arms are placed on the sides of the body, the hands are clenched into fists. Both figures wear a pleated apron and a pleated headscarf with the uraeus snake on the forehead. The only obvious difference between the two figures is the facial features: while the figure on the left looks quite youthful, the figure on the right has bags under the eyes and sunken cheeks. This is interpreted to mean that two aspects of Niuserre were represented united in this double statue: on the one hand the youthful idealized divine ruler, on the other hand the human, whose mortality is emphasized by the traces of age.

Another standing figure was found in a garbage pit in the temple of Amun-Re in Karnak in 1904 . It is almost completely preserved, but broken in two. The upper part of the statue is now in the Memorial Art Gallery in Rochester (New York) (Inv.-No. 42.54), the lower part in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (Inv.-No. CG 42003). The statue is made of rose granite . It has a total height of 8.6 cm, a width of 23.8 cm and a depth of 39.1 cm. On the base of the statue there is an inscription with the name of the king in front of the right foot. Niuserre is shown walking. He wears an apron and the royal headscarf. His left arm is placed on the side of the body. The right arm is placed on the chest, he is holding a club in his hand .

A seated statue may come from the Ptah temple in Mit Rahina ( Memphis ) and from there came to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (Inv.-No. CG 38). The statue is also made of granite and has a height of 65 cm. The king again wears an apron and the royal headscarf with uraeus. He has placed his left hand flat on his left thigh, his right hand is clenched into a fist on his right thigh. Next to the right foot there is a name inscription on the base of the statue.

Three other works are awarded to the ruler for stylistic reasons, especially because of the identical facial expression. On the one hand, there is a torso of unknown origin in the Brooklyn Museum (Inv.-No. 72.58). The piece is made of granite. It has a height of 34 cm, a width of 16.2 cm and a depth of 14.1 cm. The head and upper body from the hips are preserved. The arms are completely missing. The facial features and the headscarf resemble the pieces with inscriptions.

The second piece is another torso that was found in Byblos and is now in the National Museum in Beirut (Inv. No. B. 7395). The statue is made of granite and has a preserved height of 34 cm. The upper body from the navel, the upper arms and the head with the royal headscarf are still preserved.

Also for stylistic reasons, Niuserre is assigned the head of a statue that is now in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (William Randolph Hearst Collection, inv. No. 51.15.6). The piece is made of granite and has a preserved height of 12.1 cm. It shows the beardless king with a headscarf pleated on the lower half.

Niuserre in the memory of ancient Egypt

The cult of the dead established for Niuserre seems to have existed throughout the Middle Kingdom . Death priests and administrators of its pyramid complex and its solar sanctuary are documented for the middle and the end of the 5th Dynasty, for the 6th Dynasty and in two cases also for the First Intermediate Period , in which most of the other royal death cults of the Old Kingdom are torn down. The cult of the dead seems to have continued to a modest extent until the 12th dynasty .

The veneration of Niuserre during this period can definitely be described as that of a local saint of Abusir, which is made clear by several aspects: On the one hand, there is a strong concentration of simple private graves in the immediate vicinity of his pyramid complex. The area to the north of the mortuary temple and at the north-western end of the drive way stands out. Most of these graves date from the First Intermediate Period and the Middle Kingdom. Their owners were mostly involved in the royal cult of the dead. In addition, Niuserre became a popular namesake . His proper name Ini is found as a common part of the name of people who were buried in Abusir, for example in the forms Iniemachet, Inihetep or Iniemsaef. Forms of names such as In (i), Inii, In (i) t, Inianchu, Iniadjet, Inihor, Inihetepu, Inichenethetep, Inidedui, Inischeri and Inisenebu have been handed down from other places. Further evidence of the widespread veneration of Niuserre can be found on the false door of Ipi, which was found in Saqqara . On this, Niuserre is invoked in the so-called sacrificial formula , which is unusual because these formulas usually refer to the names of gods and only very rarely to the names of kings.

Niuserre was also worshiped outside of Abusir in the Middle Kingdom. In the temple of Karnak was Sesostris I a statue of the ruler up (now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, inv CG 42003), was probably part of a whole group of portraits of deceased kings.

During the New Kingdom was in the 18th Dynasty under Thutmose III. In the Karnak Temple the so-called King List of Karnak is attached, in which the name Niuserre appears. In contrast to other ancient Egyptian king lists, this is not a complete listing of all rulers, but a shortlist that only names the kings for which during the reign of Thutmose III. Sacrifices were made.

During the 19th Dynasty , Chaemwaset , a son of Ramses II , carried out restoration projects across the country. This also included the solar sanctuary of Niuserre, as is known from inscriptions.

literature

General

- Darrell D. Baker: The Encyclopedia of the Egyptian Pharaohs. Volume I: Predynastic to the Twentieth Dynasty (3300-1069 BC). Bannerstone Press, Oakville 2008, ISBN 978-0-9774094-4-0 , pp. 284-286.

- Peter A. Clayton: The Pharaohs . Bechtermünz, Augsburg 1994, ISBN 3-8289-0661-3 , p. 62.

- Martin von Falck, Susanne Martinssen-von Falck: The great pharaohs. From the early days to the Middle Kingdom. Marix, Wiesbaden 2015, ISBN 978-3-7374-0976-6 , pp. 139-144.

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs . Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , pp. 182-183.

About the name

- Jürgen von Beckerath : Handbook of the Egyptian king names . Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 1984, ISBN 3-422-00832-2 , p. 55 u. 182

- Karl Richard Lepsius : Selection of the most important documents of the Egyptian antiquity. Wigand, Leipzig 1842, plate 9 a – c.

- Auguste Mariette : Les mastabas de l'Ancien Empire. Fragment du dernier ouvrage de A. Mariette. Vieweg, Paris 1885, pp. 254, 255.

To the pyramid

- Ludwig Borchardt : The grave monument of the king Ne-user-re. Hinrichs, Leipzig 1907 (the excavation report).

- Zahi Hawass : The Treasures of the Pyramids. Weltbild, Augsburg 2003, ISBN 3-8289-0809-8 , pp. 252-255.

- Mark Lehner : Secret of the Pyramids. Econ, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-572-01261-9 , pp. 148-152.

- Rainer Stadelmann : The Egyptian pyramids. From brick construction to the wonder of the world (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 30). 3rd, updated and expanded edition. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7 , pp. 175-179.

- Miroslav Verner : The pyramids (= rororo non-fiction book. Volume 60890). Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-499-60890-1 , pp. 346-355.

For further literature on the pyramid see under Niuserre pyramid

To the sun sanctuary

- Friedrich-Wilhelm Freiherr von Bissing : The Re-sanctuary of the king Ne-Woser-Re. Volume I, Druncker, Berlin 1905.

- Ludwig Borchardt , Heinrich Schäfer : Preliminary report on the excavation at Abusir in the winter of 1899/1900. In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity . (ZÄS) Volume 38, Leipzig 1900, pp. 94-100.

- Ludwig Borchardt, Heinrich Schäfer: Preliminary report on the excavation at Abusir in the winter of 1900/1901. In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity. (ZÄS) Volume 39, Leipzig 1901, pp. 91-103.

- Elmar Edel , Steffen Wenig : The seasonal reliefs from the sun sanctuary of Ne-user-re (= messages from the Egyptian collection. Volume 7, ZDB -ID 1015130-8 ). Panel tape. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1974.

- Heinrich Schäfer: Preliminary report on the excavation near Abusir in the winter of 1898/1899. In: Journal for Egyptian Language and Antiquity. Volume 37, Leipzig 1899, pp. 1-9.

- Susanne Voss: Investigations into the sun sanctuaries of the 5th dynasty. Significance and function of a singular temple type in the Old Kingdom. Hamburg 2004 (Hamburg, University, dissertation, 2000), ( PDF; 2.5 MB ).

For further literature on the pyramid see under Sun Shrine of Niuserre

Questions of detail

- Jürgen von Beckerath: Chronology of the pharaonic Egypt. von Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2310-7 , pp. 14, 27-28, 39, 153-156, 175, 188.

- Bernard V. Bothmer : The Karnak Statue of Ny-user-ra. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. (MDAIK) Volume 30, Wiesbaden 1974, pp. 165-170.

- Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, London 2004, ISBN 0-500-05128-3 , pp. 62-69 ( PDF file; 67.9 MB ); retrieved from the Internet Archive .

- Peter Kaplony: King Niuserre and the annals. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. Volume 47, Wiesbaden 1991, pp. 195-204.

- Antonio J. Morales: Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom . In: Miroslav Bárta, Filip Coppens, Jaromír Krejčí (Eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague, Prague 2006, ISBN 80-7308-116-4 , p 311-341.

- Miroslav Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology. In: Archive Orientálni [Journal of the Czechoslovak Orient Institute]. (ArOr) Volume 69, Prague 2001, pp. 363-418 ( PDF; 31 MB ).

- Miroslav Verner: Abusir I. The Mastaba of Ptahshepses 1. Reliefs. Charles University, Prague 1977 (1986).

- Miroslav Verner: Abusir II. Building graffiti of Ptahschepses Mastaba. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prague 1992.

- Miroslav Verner et al .: Unearthing Ancient Egypt (Objevování starého Egypta) 1958–1988. Czech Institute of Egyptology, Prague 1990, pp. 28-31.

- Dietrich Wildung : Ni-user-Rê. Sun King-Sun God. In: Writings from the Egyptian Collection (SAS) Issue 1, Munich 1984.

Web links

- The Ancient Egypt Site (English)

- Niuserre on Digital Egypt (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Year numbers according to Thomas Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002.

- ^ Aidan Dodson , Dyan Hilton: The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London 2004, pp. 64-69.

- ^ Miroslav Verner: Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology. Prague 2001, pp. 401-404.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: Who was Shepseskara, and when did he reign? In: Miroslav Bárta, Jaromír Krejčí (Ed.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute, Prague 2000, ISBN 80-85425-39-4 , pp. 581–602 http: //egyptologie.ff.cuni.cz/pdf/AS 2000_mensi.pdf (link not available)

- ↑ Petra Andrassy: Investigations into the Egyptian state of the Old Kingdom and its institutions (= Internet contributions to Egyptology and Sudan archeology. Volume XI). Berlin / London 2008 ( PDF; 1.51 MB ), pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Petra Andrassy: On the organization and financing of temple buildings in ancient Egypt. In: Martin Fitzenreiter (ed.): The holy and the goods. On the field of tension between religion and economy (= Internet articles on Egyptology and Sudan archeology. Volume 7). Golden House, London 2007, pp. 147–148 ( PDF; 10.9 MB ).

- ^ Bertha Porter, Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. III. Memphis . 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1974 ( PDF 30.5 MB ), p. 191.

- ^ Eva Bayer-Niemeier et al .: Liebieghaus - Museum of old plastic. Egyptian sculptures / 3. Sculptures, paintings, papyri and coffins. Gutenberg, Melsungen 1993, ISBN 3-87280-080-9 , pp. 80-90, cat. 22nd

- ^ Bertha Porter, Rosalind LB Moss: Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. III. Memphis . 2nd Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1974 ( PDF 30.5 MB ), p. 146.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: Lost pyramids, forgotten pharaohs. Abusr. Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Philosophical Faculty of Charles University, Czech Egyptological Institute, Prague 1994, pp. 173–192.

- ^ Alan Henderson Gardiner , Thomas Eric Peet, Jaroslav Černý : The Inscriptions of Sinai Volume 2: Translations and commentary (= Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund. Volume 45, ISSN 0307-5109 ). 2nd edition, revised and augmented by Jaroslav Černý, Egypt Exploration Society, London 1955, No. 10-11.

- ^ Thomas Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 183.

- ^ Pierre Tallet: Les "ports intermittents" de la mer Rouge à l'époque pharaonique: caractéristiques et chronologie. In: Bruno Argémi and Pierre Tallet (eds.): Entre Nil et mers. La navigation en Égypte ancienne (= Nehet. Revue numérique d'Égyptologie Volume 3). Université de Paris-Sorbonne / Université libre de Bruxelles, Paris / Brussels 2015, p. 60, tab. 1 ( online ).

- ↑ Maurice Dunand: Foulles de Byblos. Volume 1, Paul Geuthner, Paris 1939, p. 280.

- ^ Karin N. Sowada: Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Old Kingdom. An Archaeological Perspective (= Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. Volume 237). Academic Press Friborg / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Friborg / Göttingen, 2009, ISBN 978-3-7278-1649-9 , p. 131, no. 152.

- ↑ Peter Kaplony: The cylinder seals of the Old Kingdom. Volume 2. Catalog of the seals (= Monumenta Aegyptiaca. Volume 3A). Fondation Ègyptologique Reine Élisabeth, Brussels 1981, pp. 251–252, plate 74.

- ↑ Ian Shaw, Elisabeth Bloxam: Survey and Excavation at the Ancient Pharaonic Gneiss Quarrying site of Gebel el-Asr, Lower Nubia. In: Sudan and Nubia. Volume 3, 1999, pp. 13-20.

- ↑ Günter Dreyer: Elephantine VIII. The Temple of Satet. 1. The finds from the early days and the Old Kingdom. (= Archaeological Publications. Volume 39). von Zabern, Mainz 1986, pp. 93, 148-149, no. 426.

- ↑ Hana Vymazalová , Filip Coppens: King Menkauhor. A little-known ruler of the 5th Dynasty. In: Sokar No. 17 , 2008, pp. 35-36.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner, Vivienne G. Callender: Abusir VI. Djedkare's Family Cemetery. In Excavations of the Czech Institute of Egyptology. Volume 6, Prague 2002 ( PDF; 38.7 MB ( Memento from April 7, 2013 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, pp. 324-331.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, pp. 332-336.

- ^ Miroslav Verner: Further Thoughts on the Khentkaus Problem. In: Discussions in Egyptology. (DE) Volume 38, Oxford 1997, ISSN 0268-3083 , pp. 109-117 ( PDF; 2.8 MB ).

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, pp. 341-345.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, pp. 346-355.

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The pyramids. Reinbek 1999, pp. 355-357.

- ↑ Jaromír Krejčí: Pyramid "Lepsius no. XXIV" . On: egyptologie.ff.cuni.cz of November 14, 2005; last accessed on September 18, 2015.

- ↑ Eugen Strouhal, Viktor Černý Luboš Vyhnánek: An X-ray examination of the mummy found in pyramid Lepsius no.XXIV at Abusir. In: Miroslav Bárta, Jaromír Krejčí (eds.): Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic - Oriental Institute, Prague 2000, ISBN 80-85425-39-4 , pp. 543-550 online .

- ↑ Jaromír Krejčí: The »twin pyramid« L 25 in Abusir. In: Sokar. No. 8, 2004, pp. 20-22.

- ^ Miroslav Verner: New Archaeological Discoveries in the Abusir Pyramid Field. from September 3, 2007 ( Memento from January 30, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Miroslav Verner: The sun shrines of the 5th Dynasty. In: Sokar. No. 10, 2005, pp. 45-48.

- ^ Dietrich Wildung: Ni-user-Rê. Sun King-Sun God. Munich 1984, pp. 12-21.

- ^ Sylvia Schoske: State Collection of Egyptian Art, Munich. von Zabern, Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-8053-1837-5 , pp. 44-45.

- ^ Dietrich Wildung: Ni-user-Rê. Sun King-Sun God. Munich 1984, pp. 8–11, figs. 3–6.

- ^ Dietrich Wildung: Ni-user-Rê. Sun King-Sun God. Munich 1984, p. 12, fig. 7.

- ^ Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester: Unknown, Egyptian ( Memento from December 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) On: magart.rochester.edu , last update: February 9, 2015; last accessed on September 18, 2015.

- ^ Ludwig Borchardt: Catalog Général des Antiquités Égyptienne du Musée du Caire. Nos. 1-1294. Statues and statuettes of kings and individuals in the Cairo Museum. Part 1 . Reichsdruckerei, Berlin 1911, pp. 36–37 ( PDF; 80 MB ).

- ^ Dietrich Wildung: Ni-user-Rê. Sun King-Sun God. Munich 1984, p. 12, fig. 8.

- ^ Dietrich Wildung: Ni-user-Rê. Sun King-Sun God. Munich 1984, p. 12, fig. 9.

- ↑ Brooklyn Museum: Head and Torso of a King . On: brooklynmuseum.org ; last accessed on September 18, 2015.

- ^ Dietrich Wildung: Ni-user-Rê. Sun King-Sun God. Munich 1984, p. 12, fig. 10.

- ^ The Los Angeles County Museum of Art: Royal Head, Probably King Nyuserre . On: collections.lacma.org ; last accessed on September 18, 2015.

- ^ Antonio J. Morales: Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom. Prague 2006, pp. 333–336.

- ^ Antonio J. Morales: Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom. Prague 2006, pp. 322-333.

- ^ Antonio J. Morales: Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom. Prague 2006, pp. 337-338.

- ^ Hermann Ranke: The Egyptian personal names. Volume I. List of Names. Augustin, Glückstadt 1935, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Antonio J. Morales: Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom. Prague 2006, p. 338.

- ↑ a b Dietrich Wildung: The role of Egyptian kings in the consciousness of their posterity. Part I. Posthumous sources on the kings of the first four dynasties . In: Munich Egyptological Studies. (MÄS) Volume 17, Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin, 1969, pp. 60–63.

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung: The role of Egyptian kings in the consciousness of their posterity. Part I. Posthumous sources on the kings of the first four dynasties . Munich / Berlin 1969, p. 170.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Schepseskare |

Pharaoh of Egypt 5th Dynasty |

Menkauhor |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Niuserre |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ni-user-Re; Ini; Set-ib-nebti |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | ancient Egyptian king of the 5th dynasty (around 2445 - around 2414 BC) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 25th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 25th century BC Chr. |