Panther skin

| Panther skin in hieroglyphics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old empire |

Netjeret Nṯrt fur loincloth of Cheetah / Cheetah Skin Schurz |

|||||

| Middle realm |

Ba - Abi / Ba-Aba B3-3bj / B3-3b3 Soul of the (female) panther |

|||||

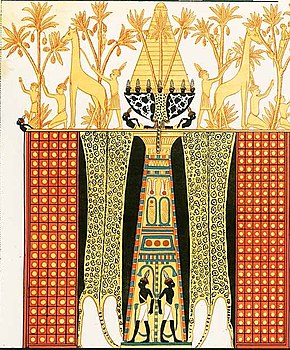

| New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty , excerpt from a mural: panther skin depiction in the private grave TT40 of Huy , viceroy of Kush ( Qurnet Murrai , Thebes-West, left rear wall). | ||||||

The panther skin (also leopard skin ) was a ritual piece of clothing in ancient Egypt . It has been reliably documented since the early dynastic period (around 3000 BC). The mythological roots go back to the time before ( predynastics ). In these epochs the goddess Mafdet still served as the sky panther, whose cosmic functions were taken over by the sky goddess Nut in the course of ancient Egyptian history . The ancient Egyptians therefore used the expression "panther skin" in connection with the divine panther .

During his lifetime, the panther skin showed the king or his designated successor as a divinely legitimized ruler. In the cult of the dead , the panther skin is mentioned in the pyramid texts as a special symbol of protection and rule of the deceased king in connection with his ascent into the sky after the mouth opening ritual . After successfully ascending into heaven, the sun god Re accepts him into divine society. The panther skin is the symbol of rule of the king, with which he undertakes his daily journey through the heavenly waters at the side of the sun god. This makes the panther skin one of the symbols that make its immortality visible. To this day it could not be equated with the leopard or cheetah .

Origins

Use of terms and origin of name

In Egyptology , the technical terms panther or leopard skin are common, whereas in German-speaking Egyptology the term panther skin is mainly used. Some additional references to a possible reference to the similar gorse cat fur are not substantiated by the written sources regarding the panther fur. The Egyptians counted the panther to the family of big cats and the divine desert animals . In this connection, several hieroglyphic representations were possible, for example in the short form as “The Divine” or as an ideogram . In the Old Kingdom (2707–2216 BC) the name of a dead deity is also translated as " Kenmet " as "leopard", although an equation with the leopard was only derived indirectly and is not certain.

In the world chamber of the solar sanctuary of Niuserre (2455–2420 BC), a larger report is dedicated to the panther in an inscription in connection with other birthing animals. All of the species mentioned there have "divinity"; they therefore “do not need a shepherd ”, but are the “determiners of fate”. An exact assignment to the cheetah or leopard is not possible, as the hieroglyph was only used in the Middle Kingdom (2137–1781 BC)

|

In the Middle Kingdom, the original name changed to the new form "Ba-Abi", which specifically meant female panthers. The mention of the associated deity Abi, first attested in the Middle Kingdom, is directly related .

Mythological connections

The panther skin was originally a costume that was worn by people very close to the king between the 1st and 2nd dynasties (3032–2707 BC); It was mostly worn by the prince's son. Since the 3rd dynasty (2707–2639 BC) panther skin wearers with the designation " Sem " have been attested, without the priesthood associated with it having already been established at that time. It is possible that there is already a reference to the god Sameref as the “loving son of the king”, who appeared mythologically for the first time around the same time .

There are no indications that non-royal persons exercised the function of a "Sem" wearing panther skin at this time, so that it is therefore likely that the king's son performed the duties of "Sem". In the 5th Dynasty (2504–2347 BC) images on royal temple reliefs of the Old Kingdom show in particular a link between ancient Egyptian official titles and the panther skin; for example, on the Sedfest representations of the Sahure in connection with the king's son wearing a panther skin, the new priesthood of "Sem" is mentioned.

Forms of representation

In predynastic times (late 4th millennium BC) different types of panther fur are shown. Bruce Williams believes it is possible that the persons depicted on vases from the Naqada IIC period (3800-3300 BC) symbolize the wearer of a panther skin. He therefore equates the ceremonial activity with a functionary as well as with that of the Tjet , which are depicted in a tomb in Hierakonpolis . However, it remains unclear in this context whether it is the fur of a panther, cattle or a cattle- like species.

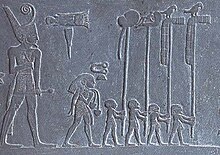

Undoubtedly the oldest illustration is on the club head of Scorpio II around 3100 BC. Occupied. The panther skin bearer is in the immediate retinue of the king. He probably carries a sheaf of ears of corn and follows a person who is throwing seeds from a basket into the ground. Further evidence is documented on the Narmer pallet and the club head of the Narmer.

On many relief representations, no spots can be seen for the panther fur, although in many cases it was certainly present in painted variants. On the few surviving colored versions in the Ramesside tombs of the kings (1292–1070 BC), the background color of the panther skin is always yellow. The characters are applied to the background color in black or white. In the Theban royal tombs are found for the panther skin in some cases additional representations with stars , reflecting the sky symbolism recalls the Panther fur.

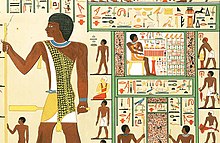

The most frequently used iconographic motifs show a fur robe that covers the entire upper body and a fur cape that only partially covers. The fur cape can be attached to the body in different ways; One possibility is to pull the fur under one arm while the two front paws are only attached to one shoulder. The other shoulder remains free. The trunk, on the other hand, is completely covered by fur.

Other variants show a front paw and the head of the panther on the shoulders or the crossing of the front paws on the chest, with both paws being carried under the arms. The panther head is usually placed over the shoulder past the neck, with the belly then uncovered. The associated hairstyle represents a side braid curled forward, often in combination with a cap-like short hairstyle. Especially in the 18th dynasty (1550–1292 BC) this manifestation was, for example, from Amenhotep I to Thutmose III. used based on ancient traditions.

Historical meaning of the panther skin

The panther skin wearer also wore the youth lock that identified him as the king's son. In iconography , the youth lock was also used in the further course of ancient Egyptian history to identify primarily those royal descendants who could be designated heirs to the throne . The eldest prince, wearing the panther skin, appeared as a mediator between the king and the world of gods as part of his priestly function as Tjet or “Sem” and as the embodiment of Sameref .

Early period (3100–2707 BC)

From the area of the earlier Hathor Temple in Gebelein comes a fragment of a relief on which the panther skin carrier can be seen in the cult of the king. The limestone block that is in the Museo Egizio Turin is mostly dated to the 2nd or early 3rd dynasty. Egyptologists interpret the actions of the panther skin wearer as a founding or hunting ritual and as a ceremony within the Sedfest. Without a doubt, however, it was a symbolic act, as the crown goddess Wenut was also involved in the event. The panther skin wearer was active in the environment of the escort of Horus , in which the exercise of royal office as the maintenance of royal rule was the dominant motive of the solemn acts.

Old Kingdom (2707–2216 BC)

In royal ritual acts of the Old Kingdom from the 5th dynasty onwards, the panther skin was exclusively the costume of the Sem priest, who among the king's priests was the person who walked in processions immediately in front of the king's litter . Wolfgang Helck makes it clear that only the eldest prince's son had the royal consent to stay in his immediate vicinity. This connection is also illustrated by the festival scenes of the Pepi II pyramid , which is why it can be assumed that the office of the panther skin wearer as Sem priest in the associated ceremonies was either occupied by the prince's son or symbolically identified as an acting person.

Middle Kingdom (2137–1781 BC)

In the Middle Kingdom, a granite document for Amenemhet III. manufactured torso the possibility that a designated king could appear as a panther skin carrier. Before his sole accession to the throne, Amenemhet III ruled. with his father Sesostris III. about twenty years together. On the granite block is Amenemhet III. with a strand of wig and a strand of pearls , the "menit". The panther skin, worn mainly on his back, ends on his shoulders.

Wolfhart Westendorf emphasizes that the iconography of the Middle Kingdom corresponds to the traditional priestly clothing of the Tjet and Amenemhet III. shows in the mythical phase of the divine Horus before he took the place of his father. In addition, Amenemhet III. the principle of the young Horus in Chemmis , embodied by the deity Iunmutef . The background was the mythological idea that the young Horus stayed at the secret place Chemmis in order to grow into a man hidden from Seth of Isis , with the panther skin Amenemhet III. as young Horus and ritual experts.

New Kingdom (1550-1070 BC)

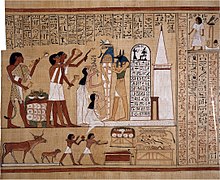

The New Reich was marked by great upheaval. Texts of the dead and coffin were combined in the Book of the Dead . The afterlife and the journey to Sechet-iaru in the Duat were now possible for everyone who was financially able to have a personal book of the dead written. Correspondingly, the panther skin belonged to the regalia of various high priests without being tied to a specific deity ; In addition, simple priests of subordinate rank were also allowed to wear panther skin.

Mainly, however, the costume of the panther skin was still associated with the office of the Sem priest. Seti I elevated the figure Horus Junmutef , previously only revered as a mystical figure, to the new deity of the dead and was appointed his panther-skin high priest. In addition, Seti I is depicted in the Amun temple in Karnak as the high priest of Amun , who accompanies the royal barge in his role as the son of gods during a procession :

“Amun sees his son who carries him, the King lifting up him who created him. My hands carry my glorious father (Amun). My body is pure because of the panther skin that's on me. "

As in the case of Amenemhet, Ramses II later, as the son of Seti I and co-ruling king, also wore the panther skin at a young age. In the mortuary temple of Seti I in Abydos , the Sameref priests of Ramses II were active in the sacrificial cult for his father Seti I in front of the royal ancestors as bearers of the panther skin. Ramses II is positioned there in the associated images behind Seti I and refers as the legitimate heir to the dynasty of the kings who ruled before him, subtitled by name .

Late period (664–332 BC)

In the late period , an expanded group of panther skin wearers was added to the mythological interpretation. It was now the dress of the queens of the kingdom of Cush in particular . The Cushitic royal mothers saw themselves in the role of the goddess Isis, who, as the mother of Horus, was responsible for the royal successors.

The queens had a decisive influence in the coronation ritual . Therefore they took over the ritual execution of the necessary ceremonies in reinterpretation of the earlier function of the Sameref as panther skin wearer. In doing so, they made the contents of the Osirism myth their own and adopted the attributes of the deity Horus-Junmutef.

The panther skin in the cult of the dead

Already in the Old Kingdom, the grave owner was often seen wearing a panther skin cloak on false doors and the entrance areas of burial chambers . In addition, there are cult acts in connection with the showing of the cattle and the provision of offerings . The panther skin does not represent an earthly office in the cult of the dead, but shows the ideal rank of the grave owner, which is achieved with the completion of the burial and enables him as the wearer of the panther skin to continue to live in the holy land of the deceased with magical powers. In the Middle Kingdom, further functions of the panther fur were added with the practice of the cult of the dead. It is a supplement to the standard equipment of the people who work in the area of the dead sacrifices; mostly the eldest son or the Sem priest, who were raised to the rank of magician and thus received the status of “divinely endowed and recognized spirits of the dead ”. Grave reliefs and steles show the newly added ritual costume parallel to the grave owner in the traditional role. With the beginning of the New Kingdom, the images of the panther fur predominate with regard to its connection in the priestly cult of the dead as a “ loving son ” and “ first of the sacrificial corps ”. In the mouth opening ceremony, however, the panther skin still retains its central role as a cult object of the deceased.

Unas (2380–2350 BC)

As the first king ( Pharaoh ), Unas had the underground pyramid chambers inscribed with reciting dead texts in the form of " death sayings ". With the use of the pyramid texts Unas established a tradition that ran through the pyramids of the kings and queens of the 6th dynasty and formed the basis for later liturgies of the dead such as the coffin texts and the ancient Egyptian book of the dead . The panther skin appears in the texts of Unas in direct relation to the cosmic rebirth of the king. The later Nutbuch describes the daily journey of the sun god Re. The dead texts that serve as a basis report parallel to the deceased king who, like Re, commutes between the horizons in order to clean himself at night after sunset in Sechet-iaru in Merencha , in order to start the day again the next morning with Re .

“It is perfect (the panther skin) for Unas and his Ka . The door leaves of the starry sky are opened for this king, that he may pass through them. His panther skin is on him, his Ames scepter is in his arm, his Aba scepter is in his hand. This king is unharmed with his flesh, it is perfect for this king with his name, this king lives with his ka. A sacrifice that the king gives so that the son will be on your throne. Let your dress be the panther skin, your dress be the chesed apron, may you walk in your sandals. "

The contents of the dead texts show that the panther skin is connected to the heavenly rule of the deceased king and also to his integrity. For the heavenly existence of this condition was necessary, given the lack of Panther Fells negative impact on the otherworldly had continued life of the deceased. With the sacrificial formula, the king is given reign over the areas of Horus and Seth, which are in the eastern sky .

Tutankhamun (1332-1323 BC)

The tomb of Tutankhamun is particularly noteworthy because of the location of the panther skin. The wall painting depicts the opening ceremony of the mouth, in which Tutankhamun's successor Eje II himself functions as a panther skin bearer and Sem priest. In addition to the numerous additions, two panther skins were found in the grave: one made of real panther skin, decorated with gold stars, with the head made of wood and covered with gold, the other is a replica made of linen .

The same motif can be seen on a group statue in the Louvre , where Tutankhamun is clad in a star-covered panther skin cloak and stands between the legs of a statue of Amun that surrounds him from behind. Both arms of the god lie on Tutankhamun's upper arms. In this representation, the symbolic father-son relationship is clearly recognizable, in which Tutankhamun appears as the “loving son” of his “father” Amun. The panther skin is the visual symbol of the family ties of Tutankhamun and Amun. In his capacity as the divine son, Tutankhamun is entitled to wear panther skin.

literature

- Jan Assmann : Death and the afterlife in ancient Egypt . Beck, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-406-49707-1

- B. Brentjes : The leopard skin in the ancient Orient . In: Das Pelzgewerbe No. 6, 1965, Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps, Berlin et al., Pp. 243-253

- Rainer Hannig : Large Concise Dictionary Egyptian-German: (2800–950 BC) . von Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-1771-9

- Ute Rummel: The panther fur as a garment in cult: meaning, symbolic content and theological location of a magical insignia. In: Alexandra Verbovsek, Günter Burkard, Friedrich Junge: Imago Aegypti, Vol. 2 - International magazine for Egyptological and Coptic art research, image theory and cultural studies. In cooperation with the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2009, ISBN 3-525-47011-8 , pp. 109–152.

- Elisabeth Staehelin: Investigations into the Egyptian costume in the Old Kingdom . Hessling, Berlin 1966.

- Jacques Vandier: Le Papyrus Jumilhac . Center National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris 1962, pp. 113-114.

- Bruce Williams: The wearer of the leopard skin in the Naqada Period . In: Jacket Phillips (ed.): Ancient Egypt, the Aegean, and the Near East. Studies in honor of Martha Rhoads Bell, Vol. 2 . Van Siclen, San Antonio 1997, ISBN 0-933175-44-2 , pp. 483-496.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Rainer Hannig: Large Concise Dictionary Egyptian-German: (2800–950 BC) . P. 470.

- ↑ Carl Richard Lepsius: Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia: Vol. III: Thebes . Hinrichs, Leipzig, 1900, pp. 301–302: private grave no. 110 according to the numbering by Carl Richard Lepsius. The proper name of the king was up to the beginning " Amun scraped" (leaf 118); no signs of the throne's name have survived. Lepsius reconstructed the cartouche entries on the assumption that the wall depiction in the private grave 110 was Tutankhamun because of the received characters for “Amun” .

- ↑ Hartwig Altmüller: The Apotropaia and the gods of Middle Egypt: A typological and religious-historical investigation of the so-called "magic knives" of the Middle Kingdom. Part 2: Catalog. Dissertation, University of Munich, 1965, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Representation of the Ethiopian gorse cat ( Genetta abyssinica )

- ↑ Christian Leitz u. a .: Lexicon of the Egyptian gods and names of gods . Peeters, Leuven 2002, ISBN 90-429-1146-8 , p. 289.

- ^ Rainer Hannig: Large Concise Dictionary Egyptian-German: (2800–950 BC) . P. 955.

- ↑ a b c Elmar Edel : On the inscriptions on the seasonal reliefs of the "World Chamber" from the solar sanctuary of Niuserre. In: News from the Academy of Sciences in Göttingen. No. 8, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1961, p. 244.

- ↑ Christian Leitz u. a .: Lexicon of the Egyptian gods and names of gods, Vol. 1: 3 - y . Peeters, Leuven 2002, ISBN 2-87723-644-7 , p. 10.

- ^ Stan Hendrickx: Peaux d'animaux comme symboles prédynastiques. Speaking of quelques representations sur les vases White Cross-lined. In: Caribéens d'Egyptologie (CdE) 73 . 1998. pp. 203-230.

- ↑ Bruce Williams: The wearer of the leopard skin in the Naqada Period . In: Jacket Phillips (ed.): Ancient Egypt, the Aegean, and the Near East. Studies in honor of Martha Rhoads Bell . Vol. 2. Van Siclen, San Antonio 1997, ISBN 0-933175-44-2 , pp. 483-496.

- ^ Henri Asselberghs: Chaos en beheersing. Documents uit aeneolithic Egypt . Brill, Leiden 1961, panel XCVIII, figure 173.

- ^ Elisabeth Staehelin: Investigations into the Egyptian costume in the Old Kingdom . Hessling, Berlin 1966, p. 36.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Ute Rummel: Pillar of his mother - support of his father: Investigations into the God Iunmutef from the Old Kingdom to the end of the New Kingdom . Hamburg 2003, pp. 31-37.

- ^ Rolf Gundlach, Matthias Rochholz: Feste im Tempel. 4th Egyptological Temple Conference, Cologne, 10. – 12. October 1996 . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1998, ISBN 3-447-04067-X , p. 223.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: Investigations into the official titles of the Egyptian Old Kingdom . In: Ägyptologische Forschungen (EgFo) 18 , Glückstadt 1954, pp. 16-17.

- ↑ Wolfhart Westendorf: The ancient Egypt . Naturalis, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-88703-712-X , p. 94.

- ↑ a b Angelika Lohwasser : The royal women in the ancient kingdom of Kush: 25th dynasty to the time of the Nastases . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2001, ISBN 3-447-04407-1 , pp. 324-326.

- ↑ Hartwig Altenmüller : The wall representations in the grave of Mehu in Saqqara . Zabern, Mainz 1998, ISBN 3-8053-0504-4 , p. 40.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: Shaman and Magician In: Adolphe Gutbub: Mélanges Adolphe Gutbub . Université de Montpellier, Montpellier 1984, ISBN 2-905397-03-9 , p. 107.

- ↑ Regine Schulz: The development and meaning of the cuboid statue type: An investigation into the so-called cube stools . Gerstenberg, Hildesheim 1992, p. 475.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Death and Beyond in Ancient Egypt . Munich 2003, p. 323.

- ^ Ogden Goelet: A Commentary on the Corpus of Literature and Tradition which constitutes the Book of Going Forth By Day. Chronicle Books, San Francisco 1998, pp. 139-170.

- ^ Elisabeth Staehelin: Investigations into the Egyptian costume in the Old Kingdom . Hessling, Berlin 1966, p. 31.

- ^ IES Edwards: The treasures of Tutankhamun . Penguin Books, Harmondsworth 1977, ISBN 0-14-004287-3 , pp. 104-105.

- ↑ Louvre E 11,609th