Perineal hernia

A perineal hernia ( syn. Perineum fracture , middle flesh break ) is a prolapse of the abdomen viscera through the body wall - referred to in medicine as a break or hernia - in the area of the perineum ( Latin perineum ). In humans, a perineal hernia is a relatively rare complication after perineal surgery. In dogs, on the other hand, it occurs frequently for an as yet unexplained cause and occurs especially in uncastrated older males. Perineal hernias are extremely rare in other animals.

A perineal hernia is caused by the decrease in the stability of the pelvic floor ( Latin: diaphragm pelvis ), referred to as the pelvic outlet in quadruped animals, so that the peritoneum bulges as a result of internal abdominal pressure . The hernial sac created in this way bulges out laterally below the anus . It usually contains fat, but internal organs such as a large network , intestinal parts , prostate or urinary bladder can also appear. A perineal hernia can be unilateral or bilateral. Affected dogs show a strong urge to defecate as well as difficulty and pain when defecating. If the urinary bladder prolapses, life-threatening urinary retention can also occur. The treatment is performed surgically.

Perineal hernia in the dog

Occurrence and development of the disease

The incidence of illness in domestic dogs is between 0.1 and 0.4%. About 95% of all perineal hernias occur in non-castrated males from the age of five. In two-thirds of cases, the hernia occurs on one side, preferably on the right. A race-related disease inclination there for Cardigan Welsh Corgi , Pembroke Welsh Corgi , Boston Terrier , German Boxer , German Shepherd , Collie , Australian Kelpie , dachshund , Bobtail and Pekingese .

The cause of a perineal hernia is a loss of the muscles of the pelvic outlet, especially the levator ani muscle (lifter of the anus), which leads to a reduced stability of the body wall in the perineal area. What triggers this muscle wasting is still unclear. Congenital or race-related weaknesses of the perineum muscles , hormonal disorders, diseases associated with the urge to defecate or difficult excretion (especially benign prostate enlargement ) or damage to the pelvic nerves ( pudendal nerve , caudal rectal nerve ) are assumed . The increased relaxin produced in the enlarged prostate could also trigger the weakness of the perineum. In sick animals, the relaxin receptor 1 (RXFP1) occurs more frequently in the perineum muscles, which could explain the muscle atrophy.

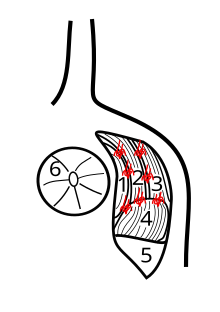

As a result of muscle atrophy , abdominal tension forces peritoneum , abdominal fat and fat from the retroperitoneum through the hernial opening. The hernial orifice is usually between the external anal sphincter and the levator ani muscle, sometimes between the levator ani muscle and the coccygeus muscle . With the progressive enlargement of the hernial sac, internal organs such as the large mesh , intestine , prostate or urinary bladder can also collapse.

Clinical picture and examination

Almost all animals show a strong urge to defecate as well as difficulty and pain when defecating. The skin bulges to the side below the anus. This increase in circumference is initially soft and fluctuating . Usually the contents of the fracture can be pushed back ( repositioned ), but this can be painful. Lifting the back of the body also usually empties the hernial sac. If the bladder has prolapsed, it can lead to urination problems and urinary retention . In the advanced stage, the skin overlying the hernial sac becomes thin, discolored blue-reddish, shows water retention or even dies .

The hernial orifice can be identified with a finger during the rectal examination . In addition, the rectum often deviates to the affected side, sometimes there is a rectal diverticulum and very often the prostate is enlarged. Imaging procedures are usually not required; under certain circumstances an ultrasound examination to clarify the contents of the hernial sac may be indicated.

Above all, tumors of the perineum and pelvic cavity , abscesses and tumors of the anal sacs, as well as a primary rectal diverticulum and prostate diseases are to be excluded .

treatment

A perineal hernia can only be treated surgically. If left untreated, the hernia becomes increasingly enlarged and defecation disorders are disturbed. The prolapse of the bladder with urinary retention is an acutely life-threatening condition.

In the most frequently used surgical technique, the external anal sphincter, the levator ani muscle and the coccygeus muscle are sutured to one another using individual staples . In addition, the origin of the internal obturator muscle is detached from the ischium , the muscle is folded towards the tail (dorsal), sewn to the aforementioned muscles and thus used to cover defects in the lower area. During the operation, the pudendal and caudal rectal nerves must be spared, as injuring them would lead to fecal incontinence . The success rate is around 80%. The sacrotuberous ligament can also be used to cover the lateral defect , with the risk of injury to the sciatic nerve .

The standard technique is particularly problematic when the muscles are already severely regressed. A reinforcement of the pelvic floor outlet by a mesh made of polypropylene or by a piece of the thigh fascia , intestinal submucosa or vaginal skin obtained from the same animal can be indicated here. During the operation, a blunt approach can also expose any rectal diverticulum that may be present and correct it surgically. The success rate of using the gluteus superficialis muscle or part of the semitendinosus muscle to cover defects is significantly lower than that of the internal obturator muscle.

In addition to wound infections and the aforementioned nerve injuries, a renewed break at the surgical site ( recurrence , incisional hernia) or, in the case of one-sided hernias, a break on the other side are possible complications. The urge to defecate, diarrhea or blood stools as well as constipation, urinary urgency and urinary incontinence have a beneficial effect . Simultaneous castration significantly reduces the risk of recurrence and leads to a significant prostate reduction within a few weeks. After the operation, the feces should be kept soft for one to two months using laxatives such as lactulose , docusate sodium or bisacodyl . With the normalization of the droppings, a fiber-rich moist food is recommended.

In complicated cases or with relapses, in addition to the standard operation, an opening of the abdominal cavity and fixation of the descending colon ( colopexy ), the vas deferens and / or the urinary bladder on the abdominal wall may be necessary. This procedure stabilizes the pelvic outlet by preventing the pelvic viscera embedded in it from shifting backwards.

Perineal hernia in humans

A perineal hernia is very rare in humans and occurs mainly in women. The first case description comes from the French surgeon Garengeot from 1743. The main causes are injuries to the perineum during operations in the perineum area ( rectal cancer operation, perineal prostate removal , tailbone removal ) or during childbirth . The prevalence after perineal surgery is 0.6 to 7%. Very rarely, a perineal hernia can also be congenital if the Douglas space in the fetus does not regress sufficiently.

The hernial orifice is either in front of or behind the transversus perinei superficialis muscle , passes through the parts of the levator ani muscle or lies between the levator ani muscle and the coccygeus muscle . The hernial sac can bulge into the labia majora . The perineal hernia can remain asymptomatic, but it can also cause chronic pelvic pain. In a differential diagnosis, all space-occupying processes ( tumors , abscesses ) in the perineum area must be excluded. The treatment is carried out surgically, with access via the perineum or laparoscopically . Nets on a synthetic basis or made from biomaterials as well as skin-muscle flaps are used for closure . Either the rectus abdominis muscle or the gracilis muscle is used to cover defects with the body's own muscles .

Perineal hernia in other mammals

In other mammals, the perineal hernia is very rare. There are only individual case reports for domestic cats , puma , striped skunk , domestic cattle , Nubian ibex and chinchilla .

literature

- MaryAnn G. Radlinsky: Perineal Hernias . In: Theresa Welch Fossum (Ed.): Small Animal Surgery . 4th edition. Mosby, St. Louis 2013, ISBN 978-0-323-07762-0 , pp. 568-573 .

- Friedrich E. Röcken: Perineal hernia . In: Peter F. Suter and Barbara Kohn (eds.): Internship at the dog clinic . 11th edition. Paul Parey, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-8304-1193-2 , pp. 773-775 .

- Robert Bendavid: Abdominal Wall Hernias: Principles and Management . Springer Science & Business Media, 2001, ISBN 978-0-387-95004-4 , pp. 635-636 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ perineal hernias , Aspen Meadow Veterinary Specialists, 2015

- ↑ a b c d e f g Friedrich E. Röcken: Perineal hernia . In: Peter F. Suter and Barbara Kohn (eds.): Internship at the dog clinic . 11th edition. Paul Parey, Stuttgart 2011, ISBN 978-3-8304-1193-2 , pp. 773-753 .

- ^ Stanley I. Rubin: Perineal Hernia. Merck Vet Manual

- ↑ R. Merchav et al .: Expression of relaxin receptor LRG7, canine relaxin, and relaxin-like factor in the pelvic diaphragm musculature of dogs with and without perineal hernia. In: Veterinary surgery: VS. Volume 34, Number 5, 2005 Sep-Oct, pp. 476-481, doi : 10.1111 / j.1532-950X.2005.00072.x , PMID 16266340 .

- ↑ a b M. Shaughnessy and E. Monnet: Internal obturator muscle transposition for treatment of perineal hernia in dogs: 34 cases (1998-2012). In: Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Volume 246, Number 3, February 2015, pp. 321-326, doi : 10.2460 / javma.246.3.321 , PMID 25587732 .

- ↑ a b c d M.G. Radlinsky: Perineal Hernias . In: Theresa Welch Fossum (Ed.): Small Animal Surgery . 4th edition. Mosby, St. Louis 2013, ISBN 978-0-323-07762-0 , pp. 568-573 .

- ↑ a b N. Khatri-Chhetri et al .: The Spatial Relationship and Surface Projection of Canine Sciatic Nerve and Sacrotuberous Ligament: A Perineal Hernia Repair Perspective. In: PloS one. Volume 11, number 3, 2016, p. E0152078, doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0152078 , PMID 27003911 , PMC 4803242 (free full text).

- ^ S. Szabo, B. Wilkens, RM Radasch: Use of polypropylene mesh in addition to internal obturator transposition: a review of 59 cases (2000-2004). In: Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. Volume 43, Number 3, 2007 May-Jun, pp. 136-142, doi : 10.5326 / 0430136 , PMID 17473019 .

- ↑ A. Bongartz, F. Carofiglio, M. Balligand, M. Heimann, A. Hamaide: Use of autogenous fascia lata graft for perineal herniorrhaphy in dogs. In: Veterinary surgery: VS. Volume 34, Number 4, 2005 Jul-Aug, pp. 405-413, doi : 10.1111 / j.1532-950X.2005.00062.x , PMID 16212598 .

- ^ AJ Lee et al .: Use of canine small intestinal submucosa allograft for treating perineal hernias in two dogs. In: Journal of veterinary science. Volume 13, Number 3, September 2012, pp. 327-330, PMID 23000591 , PMC 3467410 (free full text).

- ↑ K. Pratummintra et al .: Perineal hernia repair using an autologous tunica vaginalis communis in nine intact male dogs. In: The Journal of veterinary medical science. Volume 75, Number 3, 2013, pp. 337-341, PMID 23131842 .

- ↑ P. Szabo and G. Bilkei: Operation of the "rectal diverticulum / perineal hernia complex" in dogs with longitudinal gathering of the intestine . In: Berl. Münch. Veterinarian Wschr. tape 114 , 2001, pp. 139-141 .

- ^ JN Chambers, CA Rawlings: Applications of a semitendinosus muscle flap in two dogs. In: Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Volume 199, Number 1, July 1991, pp. 84-86, PMID 1885335 .

- ↑ HM Hayes, GP Wilson and RE Tarone: The epidemiologic features of perineal hernias in 771 dogs. In: J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. Volume 14, 1978, pp. 703-707.

- ↑ HN Brissot, GP Dupré, BM Bouvy: Use of laparotomy in a staged approach for resolution of bilateral or complicated perineal hernia in 41 dogs. In: Veterinary surgery: VS. Volume 33, Number 4, 2004 Jul-Aug, pp. 412-421, doi : 10.1111 / j.1532-950X.2004.04060.x , PMID 15230847 .

- ↑ a b D. Stamatiou et al .: Perineal hernia: surgical anatomy, embryology, and technique of repair. In: The American surgeon. Volume 76, Number 5, May 2010, pp. 474-479, PMID 20506875 (review).

- ↑ a b S. K. Narang et al .: Repair of Perineal Hernia Following Abdominoperineal Excision with Biological Mesh: A Systematic Review. In: Frontiers in surgery. Volume 3, 2016, p. 49, doi : 10.3389 / fsurg.2016.00049 , PMID 27656644 , PMC 5011127 (free full text) (review).

- ^ Robert Bendavid: Abdominal Wall Hernias: Principles and Management . Springer Science & Business Media, 2001, ISBN 978-0-387-95004-4 , pp. 635-636 .

- ↑ AM Goedhart-de Haan et al .: Laparoscopic repair of perineal hernia after abdominoperineal excision. In: Hernia . Volume 20, Number 5, October 2016, pp. 741-746, doi : 10.1007 / s10029-015-1449-3 , PMID 26643606 .

- ↑ C. Devulapalli et al .: Primary versus Flap Closure of Perineal Defects Following Oncologic Resection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. In: Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Volume 137, Number 5, May 2016, pp. 1602-1613, doi : 10.1097 / PRS.0000000000002107 , PMID 26796372 (review).

- ^ DG Ashton: Perineal hernia in the cat - a description of two cases. In: The Journal of Small Animal Practice. Volume 17, Number 7, July 1976, pp. 473-477, PMID 957624 .

- ↑ M. Galanty: Perineal hernia in 3 cats. In: Polish journal of veterinary sciences. Volume 8, Number 2, 2005, pp. 165-168, PMID 15989137 .

- ↑ M. Risselada et al .: Retroflexion of the urinary bladder associated with a perineal hernia in a female cat. In: The Journal of Small Animal Practice. Volume 44, Number 11, November 2003, pp. 508-510, PMID 14635964 .

- ↑ M. Anderson, ER Pope and GM Constantinescu: Perineal hernia in a cougar. In: Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Volume 201, Number 11, December 1992, pp. 1771-1772, PMID 1293125 .

- ^ N. Summa et al .: Successful diagnosis and treatment of bilateral perineal hernias in a skunk (Mephitis mephitis). In: Journal of zoo and wildlife medicine: official publication of the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians. Volume 46, Number 3, September 2015, pp. 575-579, doi : 10.1638 / 2013-0043.1 , PMID 26352963 .

- ↑ SM Ishaque: A case of perineal hernia in a bovine. In: The Indian veterinary journal. Volume 26, Number 5, March 1950, pp. 419-420, PMID 24537585 .

- ↑ A. Tadmor: Perineal hernia in a Nubian ibex. In: The Veterinary quarterly. Volume 4, number 3, 1982, pp. 142-144, doi : 10.1080 / 01652176.1982.9693855 , PMID 7147674 .

- ↑ M. Thöle et al .: Case report: Perineal hernia in a chinchilla . In: Small Animal Practice . tape 61 , no. 7 , 2016, p. 399 .