Seymour Hersh

Seymour Myron "Sy" Hersh (born April 8, 1937 in Chicago , Illinois ) is an American investigative journalist ; Until 2015 he was a regular contributor to the weekly magazine The New Yorker .

Seymour Hersh became world famous in 1969 when he exposed the US Army's war crimes in the My Lai massacre during the Vietnam War . In 2004 he published on the torture scandal of the US Army during the Third Gulf War in the Iraqi Abu Ghuraib prison .

Live and act

youth

Seymour and his twin brother Alan Hersh were born into a Jewish Eastern European family with older sisters, also twins. His father Isador Hershowitz came from Lithuania and emigrated to America in 1921. At that time he had changed his name to Hersh and had received American citizenship in 1930. Hersh's mother, Dorothy Margolis, immigrated to the United States from Poland . The parents ran a dry cleaner in the South Side district , the Hershs apartment was in Chicago 's Hyde Park district . Yiddish was spoken in the household and with customers , but Judaism did not play a major role in family life. The family deeply rooted belief in American values shaped Hersh's idealistic attitude to want to expose grievances. Hersh graduated from the University of Chicago and graduated as a historian in 1958. There he met Elizabeth Sarah Klein, a psychoanalyst, whom he married in 1964. After studying history, Hersh worked in the drugstore chain Walgreens , began studying law, but dropped out due to poor performance, whereupon Walgreens hired him again.

First journalistic work

In 1959, the year his father died, Hersh began his journalistic career as a police reporter at City News Bureau (CBS). 1960 Hersh joined the military service in Fort Leavenworth ( Kansas ) and completed a three-month basic training. Because of his graduation and work at CBS, Hersh then served as an Information Specialist in Fort Riley , Kansas. Here he got to know firsthand the public relations of the US military, which was useful in his later work as a Pentagon correspondent for the Associated Press (AP) news agency .

In 1961, Hersh returned to Chicago and co-founded the neighborhood newspaper Evergreen Dispatch with former CBS editor Bob Billing . After a year he gave up the company. He was at odds with Billing, who was doing the editorial , about the direction of the paper and there were financial difficulties so the paper was shut down. The following year, America's second largest news agency United Press International (UPI) hired him in South Dakota . Hersh was proud of a series of articles about the Sioux Indian tribe whose poor living conditions on the Pine Ridge Reservation he described, which was picked up by the Chicago Tribune .

Pentagon correspondent for the Associated Press

Because South Dakota Hersh was too provincial, he returned to Chicago and found employment with the Associated Press (AP) in 1963 . Together with later Pulitzer Prize winners such as James Polk, Gaylord Shaw and others, Hersh began work as a newcomer to the revision of texts by established journalists. Over the next few years, his reputation rose thanks to good stories that were regularly featured in the AP's internal newsreel. In 1965, AP transferred him to Washington, DC. He reworked the stories of other journalists, but Hersh found stories himself with a flair. For example, he did an exclusive interview with Martin Luther King Jr. His initiative and instinct made headlines for his articles .

In addition to the civil rights movement , the reporter dealt increasingly with the military and influenced the debate on the selection of conscripts during the Vietnam War with his articles . In 1966, he continued to delve into the military as a Pentagon correspondent for the Associated Press. He earned a reputation at the Pentagon for preferring to meet his sources in the officers' mess rather than appearing at press conferences.

His reports that at the beginning of 1967, for the first time, more soldiers were deployed in Vietnam than in the Korean War and that the civil infrastructure was being bombed, worried his superiors. His reporting was made more and more difficult by AP internal text abbreviations. Still, Hersh revealed that the US Army was storing poison gas abroad . The editors of the AP demanded to weaken the story (reduction to 1/10 of the original text), which Hersh refused; he resigned and sold the item to the New Republic .

Campaign advisor

1968 committed Hersh for the nomination of the Democratic Senator Eugene McCarthy for the presidential candidate as his spokesman. He worked, so to speak, as a public relations agent for the “dark side” from the point of view of journalism. He hoped for an end to the Vietnam War from McCarthy , as he was one of the most prominent rejecters. However, three months later, Hersh left the campaign team after an argument with McCarthy.

Freelance journalist

Following on from his research on chemical and biological weapons , Hersh worked as a freelancer for the New York Times and New Republic . The US government tried to prevent publications on the subject. Undeterred by this, after several series of articles, Hersh published his first book in 1969: Chemical and Biological Warfare: America's Hidden Arsenal . Among other things, he described in it that the United States of America had become the largest producer of the weapons banned under the Geneva Conventions and that these were specifically used in Vietnam. Scientists like Charles J. Thoman as a representative of the " military-industrial complex " criticized Hersh as a proponent of disarmament. Nonetheless, the book gave him an informed commenter status, who commented on the subject in other articles. President Richard Nixon stopped the production and storage of such weapons in response to Hersh's book, among other things.

According to scientist John Ellis van Courtland Moon, who studied America's biological arsenal, Hersh has cast the public voice on a pre-existing sentiment of chemical and biological weapons disarmament. The critic David Rubien wrote in retrospect in 2000 that Hersh's book already represented the typical character traits of his oeuvre. On the positive side, according to Rubien, there is the extremely meticulous research and the complete penetration of the topic, as manifested in the source apparatus and footnotes. On the negative side, Rubien records a writing style that takes anything but a neutral standpoint, so that Hersh exposes himself to the accusation of bias without need. Nevertheless, Rubien thinks that Hersh's work "survived" because of the positive aspects.

My Lai massacre

Also in 1969, Hersh had his breakthrough on an international level. Hersh got a tip from the journalist Geoffrey Cowan , who at the time reported in an article about Operation Phoenix details, including the fact that the CIA had murdered Vietnamese civilians suspected of helping the Viet Cong . Cowan had an informant at the Pentagon who informed him, and thus Hersh, that a US officer had been charged with the murder of civilians in Vietnam and that this case should be covered up. Hersh followed up on the trail after protests by the peace movement had recently taken place and President Nixon was trying to win public opinion for the continuation of the Vietnam War , with the media obediently following along, although critical voices rose. To investigate the story, Hersh asked philanthropist Phillip J. Stern for money. Hersh managed to track down the lieutenant ( William Calley ) who was officially charged with killing over 90 people. He learned the whereabouts of Fort Benning , not least because the lieutenant's deed was known to many GIs at the base. Later in the story it turned out that Calley, as the commander of a unit, was jointly responsible for the massacre of more than 500 people, including 182 women ( in the language of the US soldiers, My Lai 4 ) in March 1968 in the Vietnamese town of Son My ( 17 pregnant women), 173 children (56 infants) and 60 men; there had also been rapes.

Hersh interviewed Calley, who, while drunk, did not even have a complete picture of the extent of the incident. With Calley's attorney, he denied proofreading of his article. For the report, Hersh relied on the statements of eight out of ten anonymous sources that he had found within another five months of research. As part of an effort to get the story out, the magazines canceled Life and Look . Hersh then offered the story to David Obst at the Dispatch News Service . Claiming other newspapers interested, the November 15 article about the My Lai massacre made it to 35 newspapers including the Boston Globe , Miami Herald , Chicago Sun-Times , Seattle Times and New York's Newsday . As the historian Kendrik Oliver noted, major newspapers stayed a few days away from reporting because other events distracted attention from the article - for example, the moon landing of Apollo 12 on November 19 was a major event. Hersh then interviewed other participants in the company involved in the massacre and wrote follow-up articles.

Hersh got "exclusive access" to Paul Meadlo, one of the soldiers involved, of whom he was an agent. Meadlo described his experiences on the television station CBS with great public attention. Hersh's research and publications were followed by a counterattack by the US government. From President Nixon's standpoint, war critics like Hersh should be discredited . Hersh's client Meadlo was denigrated as untrustworthy because the interview was accompanied by a payment of US $ 10,000 , which Hersh and Obst used for research. In addition, pro-government newspapers accused Hersh of being an unpatriotic traitor and communist . Regardless, Hersh's coverage of the Calley Trial and his reports on eyewitnesses to the massacre raised the pressing question of whether the soldiers had received instructions. On December 8th, Nixon announced that My Lai was an "isolated incident". It turned out that the army leadership knew about the massacre but looked the other way and tried to cover it up.

The reports on the My Lai massacre subsequently brought not only Hersh fame, but also the definitive change in sentiment in America regarding the Vietnam War. From 1961 to 1967 the press was by no means a “ watchdog of freedom, ” the independence of the media was very limited, stated the political scientist Daniel C. Hallin in his book on the press during the Vietnam War. A change began with Hersh. Newspapers now ran reports on similar incidents. 1970 appeared Hersh's detailed book My Lai 4: A Report on the Massacre and Its Aftermath , which he had published by Random House ; He received $ 40,000 for the reprinting rights alone. In the same year he received the Pulitzer Prize for his work .

Hersh accompanied Calley's trial and described the investigation in the 1972 book Cover-Up: The Army's Secret Investigation of the Massacre at My Lai . The book was not selling well. Hersh blamed a mood in which, given the imminent defeat of the USA, nobody was interested in the subject of Vietnam anymore.

All of Hersh's articles at the time were based on research in Washington and the United States. It was not until 2014 that he traveled to My Lai for the first time and had conversations with survivors and local experts. Robert Miraldi as well as the historian Oliver describe the disclosure of My Lai as a turning point in the Vietnam War. She also changed the press work and created an agenda in which Hersh followed the story while the press ignored it and reporters in Vietnam did not touch it either. Oliver goes on to say that without Hersh the incident would have been a mere piece of news, such as a report on the Calley trial or just a description of the incident by a later historian. The circumstances made the event a sensation.

At the New York Times

From 1972 to 1978 Seymour Hersh worked for the New York Times , first for the Washington DC branch and from August 1976 at the headquarters in New York City .

Lavell affair, Watergate

Hersh's first assignment as Washington correspondent for the New York Times was to accompany the peace talks on the Vietnam War in Paris. As part of the John D. Lavelle affair, Hersh revealed that the Air Force officer had been ordered from the highest level to bomb North Vietnam. The fact that Lavelle was following orders from superiors only came to light much later, because the Nixon government initially did not exonerate Lavelle. The officer's family resented Hersh's six-month period of accusations. As part of a 2007 investigation, the rank and reputation of Lavell, who died in 1979, was posthumously restored. Hersh got at this time the stamp "Troublemaker" (English for "troublemaker, troublemaker"). That same year, Hersh revealed in an editorial that the CIA had attempted to censor a book by historian Alfred W. McCoy about the agency's extensive drug trafficking activities during the Vietnam War . In June 1972, the coverage of the Watergate affair developed . The trigger, a break-in, was already the capital's house paper, the Washington Post , on the trail of Hersh's eternal competitors Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein . Hersh joined the New York Times in January 1973 with the first headline article . He had a decisive influence on the reporting of 1973 and '74, he had written the hardest articles, according to the judgment of John Deans , who was an advisor to President Richard Nixon at the time; at the end of the Watergate scandal, Nixon was forced to resign. Others see his contribution, but it is behind the competitors of the Post . From the perspective of the CIA, Timothy S. Hardy says that while Hersh doesn't get a footnote in the story for not removing any of the players, he initiated President Richard Nixon's resignation.

see section: CIA wiretapping scandal and family jewels

Secret bombing of Cambodia

In 1973, Hersh dealt with secret bombings in Cambodia . During Operation MENU between 1969 and 1970, suspected hiding places were attacked by Viet Cong troops, including hospitals. An informant, Hal M. Knight, who had been following the reports of the Lavelle affair, realized his responsibility and wrote a letter to Wisconsin's Senator William Proxmire , which indirectly reached Hersh. The revelations embarrassed the Pentagon and the White House . When the articles appeared, the US administration admitted the operation and a committee of inquiry was established. It was also revealed that President Nixon had been tapping National Security Council and Pentagon phones since 1969. As part of the investigation, which Hersh accompanied with articles, US Secretary of Defense Melvin R. Laird pointed out that the orders for the bombing had come from the highest level of government, that is, directly from President Nixon and Henry Kissinger . An impeachment procedure was then sought by members of the Congress , but this was not voted on.

Government overthrow in Chile

Referring to the previous revelations, in 1974, according to Robert Miraldi Seymour Hersh, was the " Golden Boy " of the New York Times . That same year, the journalist revealed that the CIA in Chile the local coup against the democratically elected socialist president Salvador Allende funded with eight million dollars. The "Committee of 40" , Kissinger was a member, had given permission for destabilization. Again the White House denied participation. But Hersh was able to confirm involvement in the coup with the allegations of CIA insider Ray S. Cline . In a "smear campaign" against the US Ambassador to Chile Edward M. Korry , the allegations escalated in an attempt to prove his responsibility to Kissinger. It wasn't until later that it was discovered that Hersh had been wrong and Korry had been passed over. The New York Times printed an apology in the longest front-page article to date. Hersh's main target, Henry Kissinger, whom he had viewed as a war criminal since Vietnam , got away unscathed.

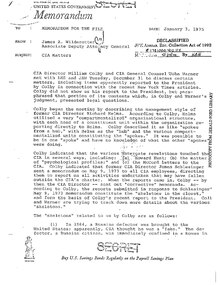

CIA wiretapping scandal and family jewels

Another 1974 issue was domestic spying by the Central Intelligence Agency, code-named Operation CHAOS . A CIA insider drew Hersh's attention to the action in April. After researching scattered details, Hersh presented the existence of the " family jewels " of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to public opinion for the first time with the article: Huge CIA operation reported in US against antiwar forces, other dissidents in Nixon years of December 22, 1974 , it was a 693-page collection of files that mostly brought together illegal operations by the agency from the 1950s to the 1970s. There were 34 follow-up articles in the New York Times alone .

For exposing the illegal activities of the CIA, Hersh was initially attacked by the American press, for example by the Washington Post or Newsweek . Hersh and his editor Abraham Michael Rosenthal , who offered Hersh support, stood alone at this point. To investigate Hersh's allegations, President Gerald Ford appointed the Rockefeller Commission of Inquiry . In addition, the Pike Committee was set up in early 1975 to investigate the activities of the CIA, after which the United States House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence was established as a permanent secret service committee. Hersh's revelations were also a major reason for the appointment of the Church Committee of the US Senate , which for the first time systematically examined the activities of the US intelligence services . As a result of the exposure, the CIA underwent extensive reforms.

Walter Pincus wrote in the New Republic that nothing since Watergate has made such an impact on the government as Hersh's article. In Timothy S. Hardy's assessment, Hersh alone managed to make intelligence-gathering a major topic of 1975, which neither President Ford nor Congress could have eluded. It was precisely because of this that Watergate became the event in the United States that it represents today. According to Robert Miraldi, as a result of his discovery, Hersh became a favorite of the American media at the time. The journalism changed now, with Hersh's presence was of investigative journalism to fashion. Times editor Arthur Sulzberger wrote to his newsroom, "All reporters should be 'investigative reporters,' whatever that stands for." Teams of investigative journalists became the norm and an organization called Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE) was formed in 1975 .

Project Jennifer

Hersh researched the circumstances of the Azorian project , which he named the Jennifer project . The CIA had the Hughes Glomar Explorer converted in complete secrecy to lift the Soviet submarine K-129 , which sank in 1969 . The CIA convinced the Washington Times editor-in-chief Clifton Daniels to withhold the story "in the national interest." A confrontation with the USSR was feared if it learned that missile technology and launch codes were being recovered. In August 1974 an attempt at elevation was made. Documents had been stolen from a break-in beforehand, so that the first details leaked to the public in February 1975 through reports in the Los Angeles Times . Hersh published the article on the subject in March 1975, previously he had not been allowed to write about it; this was the first detailed account of what happened. The files on the project were released in 2012.

Change to the headquarters

In 1976, Hersh followed his wife Elizabeth to New York to study at the University's Medical School . During his time as a reporter at the headquarters of the New York Times , he and his colleague Jeff Gerth published articles on Sidney Korshak about his mafia involvement in bribery, fraud and extortion. In his last tenure, he used several key articles to discredit the business practices of the Gulf and Western Industries concern; After investigations by the US Securities and Exchange Commission, they led to two lawsuits. In 2015, the journalist Mark Ames took up these revelations about unbridled companies in order to express criticism of today's Muckraker journalism, which is only aimed at government misconduct, but is no longer in the original meaning of criticism of companies and corporations; it is remarkable what Hersh did at the time. Hersh's biographer Robert Miraldi noted that corporate disclosures were both an attempt and a failure.

The Price of Power

Hersh wrote his book The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House over the next four years . In it he expressed his controversy with Henry Kissinger, which had lasted for over a decade, and whose “ nemesis ” he was after his biographer Robert Miraldi. Kissinger declined to conduct an interview with Hersh, but the journalist included over 1,000 other interviews in the book, some by name and, according to his custom, also as anonymous sources. The historian Walter LaFeber wrote that Kissinger had left behind an astonishing number of dissatisfied former confidants, all of whom Hersh probably found. His book became a bestseller as early as 1983, for example it was awarded the American Book Critics Circle Prize as best book of the year . It was the culmination of Hersh's anti-Kissinger work. He justified his opposition to Kissinger with his orders to bomb civilians in Vietnam and Cambodia. Hersh commented on this engagement with the following words:

"When the rest of us can't sleep we count sheep, and this guy [Kissinger] has to count burned and maimed Cambodian and Vietnamese babies until the end of his life."

"If the rest of us can't sleep, we count sheep, and this guy [Kissinger] has to count burned and mutilated Cambodian and Vietnamese babies by the end of his days."

More revelations

In 1985, after six months of research, Hersh published that Pakistan had tried to obtain devices that could be used as detonators for nuclear weapons , and accused the government of Pakistan of trying to become the seventh nuclear power in the world. Pakistan denied this, but actually developed the weapon and successfully tested it for the first time in 1998.

In 1986, Hersh published an article in the New York Times about Manuel Noriega , the ruler of Panama , who was also involved in the Iran-Contra affair . According to Hersh, Noriega received secret documents in the mid-1970s and passed them on to Cuba; he also sold American technology for three million dollars to Eastern European countries, which at the time were members of the Warsaw Pact military alliance . Three years later, Noriega, who had cooperated with the CIA since 1967, was overthrown and taken into custody by the US military during the US invasion of Panama and then tried and convicted. Hersh followed up and published articles about him in Life magazine.

In the same year his book The Target Is Destroyed: What Really Happened to Flight 007 and What America Knew About It was published , in which he investigated the downing of the South Korean passenger plane by the Soviet Union . For his research he was invited to Moscow for five days , where they wanted to convince him that it was a secret US operation. However, Hersh rejected this and described in great detail in the book that it must have been a programming error that brought the plane into the airspace of the Soviet Union, whereupon it was accidentally shot down as a spy plane. The reviews have been positive, despite the use of even more anonymous statements than ever before.

Israel's nuclear weapons program

Hersh dealt with one of Israel's open secrets in The Samson Option , which appeared in 1991 and which brought the public's attention to Israel's secret nuclear weapons program . Israel, which had received nuclear technology from France for civil use, built a nuclear research center in the Negev desert near Dimona . After long negotiations, Israel allowed IAEA inspections , but Hersh's research only entered a dummy control room. This double game of Israel and its unexpectedly large nuclear weapons potential as well as the tolerance by the United States was shown by Hersh. Some larger newspapers such as the Times brought further articles and picked up on Hersh, who had dealt with much that was already known, but added it in great detail. The book became a bestseller in Europe, but in Hersh's home country interest quickly fell after a good sales start. Last but not least, Hersh was accused of being a self-hating Jew . This emerging attitude was reflected in the reception of the book. Now the so often used anonymous sources were interpreted negatively. There he referred to press magnate Robert Maxwell and his colleague Nicholas Davies as Mossad agents. Hersh was charged with defamation , but the two lost the ensuing trial.

Kennedy biography

In 1997, Hersh attempted a comeback with the Kennedy biography The Dark Side of Camelot . In it he accused the Kennedys of being involved in organized crime , such as the Irish mafioso Kenny O'Donnel, or of being involved in election fraud . But Kennedy's affairs were also part of it . Hersh received documents from a Lawrence X. Cusack via a Thomas Cloud, which were supposed to show that Kennedy had an intimate relationship with Marilyn Monroe . In the run-up to the book publication, there should be a report by the broadcaster ABC . As ABC pressed for confirmation of authenticity, the documents were examined and turned out to be falsified. Hersh had followed a wrong track. Nevertheless, the book became a bestseller and the reactions were far more extensive than the book itself. Its reputation was now considered ruined, its credibility suffered. The majority of the reviews were bad, such as that of the Kennedy's house historian Arthur M. Schlesinger , who wrote that he was "the most gullible investigative reporter [he] has ever met." political content, like Thomas Powers or Voices from the Center for Presidency and Congress Studies , found that the book had improved understanding of Kennedy's tenure.

Gulf War Syndrome

In 1998, Hersh published Gulf War Syndrome: The War between America's Ailing Veterans and Their Government on Gulf War Syndrome . It describes the mysterious syndrome that afflicted veterans of the Second Gulf War in 1990/91 and their problems with the US military bureaucracy . In it he asked whether the 15% returning soldiers only suffered from war fatigue or were exposed to B and C weapons. Ultimately, the question went unanswered and there was no clear culprit. The book was unsuccessful.

Massacre during the second Gulf War

In 2000 he published in The New Yorker magazine that during the second Gulf War an American unit led by two-star General Barry McCaffrey was involved in several massacres of Iraqi units that had already surrendered and of civilians. McCaffrey publicly protested against allegations that he had ignored his superiors' orders for a ceasefire . However, the allegations were substantiated by the large number of interviews. Hersh also indicated in his 34-page article that several previous military investigations into the allegations had been inadequate and one-sided.

9/11 and Abu Ghuraib

After the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 , Hersh got buoyant again. 20 stories about background and sloppiness were created in this context. In the New Yorker , for example, the article King's Ransom appeared , which deals with the financing of al-Qaeda and other extremist groups by the Saudi Arabian royal family . The article also analyzes the relationship between the royal family and the administration of President George W. Bush . With a report about a badly planned operation to capture Mullah Ommar by the special forces of the Delta Force , who got into an ambush, Hersh caused a stir again. With his articles on the Near and Middle East he became a voice against the embedded journalism of the Pentagon. Once again, his reports were unmasking for those in power, this time the administration of George W. Bush. In the Who Lied to Whom? he investigated the false claims about weapons of mass destruction that served as legitimation for the Iraq war .

In the spring of 2003, Hersh was first told by a two-star Iraqi general that abuse was taking place in US prisons. Hersh's dissatisfaction with the White House's account of the course of the war in Afghanistan since 2001 was supported by a source in 2004. Al-Qaeda continued to control large areas of Afghanistan and the heroin trade was flourishing. Outside of smaller articles and human rights organizations , little was known about the mistreatment of prisoners. Hersh knew about the media effect of images since his My Lai report. Through a woman whose daughter was a guard in Abu Ghraib, Hersh was given access to photos documenting the abuse of prisoners. On April 28, 2004, Hersh was the first reporter to write an exposé on torture and dehumanization in the US prison in Abu Ghraib . Three more articles in the New Yorker followed: “No apologetic statements or political spin last week could cover up the fact that President Bush and his chief advisors have been embroiled in a war on terrorism that the old rules don't have since the 9/11 attacks apply more. ”With his report, Hersh won the fifth George Polk Award from Long Island University in New York.

Hersh summarized the reports in the book Chain of Command: The Road from 9/11 to Abu Ghraib . The Canadian historian, politician and journalist Michael Ignatieff wrote in the New York Times about the book that it was comparable to the revelations of My Lai and that questions arose again about compliance with the Geneva Conventions for prisoners of war. Hersh himself considered the crimes in Iraq to be more serious than Vietnam in the long term: “My Lai was bad, but the Vietnamese do not want to be our enemies forever. Strategically speaking, Abu Ghraib is much more dangerous ... The Arabs will never forgive us, especially not the moderate ones who matter. We have drawn the hatred of 1.3 billion Muslims "()

At the same time as Chain of Command , the second book of his longtime competitor Woodward, Plan of Attack, was published . Woodward describes the story from the perspective of the White House. Mark Danner, author of a book on the Abu Ghraib torture scandal, said Woodward's book was an important official account that provided deeper insights into the government. On the other hand, Hersh's report is the version that the government wants to withhold from the public - "a version that contradicts the official story, so to speak." After 10 years of working with Hersh, David Remnick, editor of the New Yorker , said that he had transformed the magazine into a source of information that could unleash great national defense stories and thus influence war.

Lebanon War 2006

On August 14, 2006, an article appeared in the online edition of The New Yorker magazine in which Hersh contradicted the official account of the Israeli attack on Lebanon in July 2006. He cited numerous anonymous American and Israeli sources from close government circles that Israel had planned the war months in advance. The US government had also been consulted by Israel months in advance. This account blatantly contradicted the official version, according to which the Israeli attack came as a kind of spontaneous reaction to the kidnapping of two Israeli soldiers. Hersh also reported that the US government saw and promoted the campaign against Hezbollah as a test case for an American attack on Iran, which was planned before the end of President George W. Bush's term in office . Hersh had already obtained the official denial of the US government to his core statements in advance and incorporated it into his article.

In September 2007 Seymour Hersh received the paper's democracy prize for German and international politics .

Political killings under the administration of George W. Bush and Barack Obama

On March 10, 2009, during a speech at the University of Minnesota , Hersh announced that he had intelligence on a secret execution unit. The latter is committing murders abroad on behalf of the US government and reports directly to Vice President Dick Cheney . Another participant in the event was former US Vice President Walter Mondale , who stated, “Cheney and the others ran a government within the government that was not accountable to Congress. That is worrying. ”The special unit had been active in at least 14 countries in the Middle East, Latin and Central America and had liquidated target persons on the basis of a list. Stanley McChrystal , who previously headed the special command from 2003 to 2008, was responsible for the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) from mid-May 2009 . There was a commitment to carry out executive actions . This term has been synonymous with political murders since the 1950s . President Gerald Ford had banned executive action by decree EO 11905 of February 18, 1976 after the Church committee in which CIA murder plans of statesmen and important people were exposed . This ban was reaffirmed by President Ronald Reagan's successor in 1981. Even under McChrystal's successor, the three-star Admiral William H. McRaven, the JSOC unit carried out such actions. On the day of the lecture, an article appeared in the New York Times that reported that McRaven ordered command operations to be suspended for two weeks because of "so many collateral deaths."

The existence and mandate of the execution unit have been confirmed by employees of the Bush administration. According to Vice President Cheney's former security advisor, John Hannah, the practice was "completely constitutional and completely legal." He confirmed that there was "the list of authorized targets who can be killed without a trial." During the presidency of George W. Bush, attempts were made to circumvent the prohibition on the grounds that political murders do not occur in wartime because one is at war with al-Qaeda. As early as 1989, under the Bill Clinton administration, there was a secret paper, which came from the legal department of the United States Department of Defense, in which it was argued that the murder prohibition only applies to an "intentional killing" of foreign leaders, but to an "accidental death". Killing ”during a coup or an invasion is invalid. The spokesman for the United States Special Operations Command , to which the execution unit was subordinate, denied Hersh's charge, stating that the special units operated “under established rules of engagement and the law of armed conflict”. When and to what extent the executive unit in Afghanistan - after Vice President Cheney was no longer in office - continued to operate was unclear until then.

When reporting on Hersh's allegations, Horst Schäfer noted that these only played a marginal role in the American media and, with the exception of this, only reported on MSNBC and CNN . Even three weeks after Hersh's speech, the National Intelligence Examiner found that the lack of reporting led to a lack of argument. With a few exceptions, according to Schäfer, established German media also "fell into a comatose, almost unmasking silence."

Journalist and extrajudicial execution expert Jeremy Scahill said these things were taboo "in political America" when asked by news channel n-tv about his book: Dirty Wars. America's secret commando operations , which provide evidence of the existence of the execution units and the responsibility on the part of Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld . He explained, “They put the unit on steroids and released it into the world. That went on for many years [...]. ”Also after Barack Obama took office, the JSOC had become even more important than it already was, and would be a central method with the motto:“ We will bring about victory. ”

Poison gas attacks in Syria in 2013

Originally ordered by the New Yorker , but then rejected by the Washington Post , the article Whose sarin? on December 19, 2013 in the literary journal London Review of Books . Hersh examines the Ghouta poison gas attack in Syria on August 21 and questions the official account of the American government. According to Hersh, despite claims to the contrary, the Obama administration had no evidence of an impending attack with the poison gas sarin . The media had failed, they accepted the White House statements without further inquiry and ignored the findings of scientists. The weapons expert Theodore Postol from MIT stated in a study that the missiles used were "very likely" manufactured on site. However, this contradicted the official presentation of the US government and was therefore not taken up by the New York Times , but Postol previously published an article in collaboration with Richard Lloyd, which reported on the evidence of sarin. Before the attack, the US secret services had reports that showed that the Al-Nusra Front was able to produce large quantities of the war gas. Obama argued in his TV address on September 10th, however, that intelligence service witnesses and UN inspectors had identified the government under Bashar al-Assad as the perpetrator, although the Al-Nusra Front should have been included in the group of suspects. The UN report of September 16, however, leaves the perpetrators open, according to Hersh. The investigators carefully noted that they had only been granted access to the sites of the attack five days late and only under the control of the rebels. “As in other locations,” the report warned, “the premises had been well visited by other people prior to the mission's arrival ... During the time at these locations, persons carrying other suspicious weapons arrived, an indication that such potential evidence is postponed and possibly manipulated. " Frank Nordhausen , Turkey correspondent for the Berliner Zeitung , doubts the account that Ankara has equipped groups close to al-Qaeda with poison gas:" Hersh does not provide any hard evidence for this. He only refers to conversations with his US informant, whose name he does not give. Hersh also works primarily with insinuations, hearsay statements and unidentifiable sources. Wherever it becomes concrete, its arguments are weak or demonstrably wrong. "()

Killing of Osama Bin Laden

Hersh published the investigative report The Killing of Osama Bin Laden in the London Review of Books on May 10, 2015 . The text appeared in German in Lettre International No. 109 in June. Hersh wrote that the Obama administration had systematically deceived the public about the finding and shooting of Osama bin Laden on the night of May 2, 2011. The killing of bin Laden was an important factor in Barack Obama's re-election, Hersh said, and he denies the portrayal that it was purely American action. According to the government version, US secret services tracked down bin Laden after long, meticulous work without the knowledge or help of the Pakistani authorities; Soldiers from the SEALs special forces unit single-handedly shot bin Laden in a firefight during Operation Neptune's Spear . His body was buried at sea on the US aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson according to Islamic rules . According to the government narrative, this happened without the knowledge or assistance of the Pakistani secret service or the military.

Contrary to the representation of the US government, according to Hersh, bin Laden was by no means hiding in the complex in Abbottabad , but had been a prisoner of the Pakistani military intelligence agency Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) since 2006 after tribal leaders in the Hindu Kush had betrayed him. He lived under house arrest at the property with his wives in the middle of the military secure zone in Abbottabad, two miles from Pakistan's Kakul National Military Academy, three miles from a Pakistani Army command post and an intelligence base. That was the reason for bin Laden's placement in Abbottabad, the ISI kept him under "permanent surveillance," explained Hersh. The ISI used bin Laden as leverage in negotiations with the Taliban and al-Qaeda ( quid pro quo ).

Hersh describes that in August 2010 a former ISI officer provided Jonathan Bank with information about bin Laden's whereabouts to the station chief of the CIA at the US embassy in Islamabad, Jonathan Bank . In return, he received part of the $ 25 million bounty that the United States had abandoned after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 for evidence of arrest, and he was granted US citizenship for himself and his family, and lived in the Washington area , DC and became a CIA advisor. It was through him that bin Laden's whereabouts became known to the Americans. The whereabouts were not revealed through waterboarding or any other form of torture .

According to Hersh, Pakistan's army and secret service also played a stronger role than had previously been admitted in the preparation and execution of the US military operation Neptune's Spear by the SEALs. The Pakistanis agreed to the formation of a four-man cell - a SEAL, a CIA agent and two communications specialists were allowed to set up a liaison office in Tarbela Ghazi, the location of an ISI base for covert operations. Before the access, the Pakistanis withdrew their guards from the property and the electricity in the city was switched off. An ISI agent is said to have then led the US soldiers into the property and to bin Laden's quarters. A former SEAL commander who was involved in similar missions told Hersh that bin Laden was not allowed to live and that the soldiers on such missions would be aware that they would commit murder. The United States government, on the other hand, had repeatedly declared since bin Laden's death that he would have been left alive if he had surrendered immediately. According to Hersh's account, bin Laden did not reach for a weapon when he was shot, nor did he try to use one of his wives as a human shield. Rather, he was seriously ill and there should have been no resistance to his arrest. Likewise, no “real treasure” of terrorist documents had been seized by the SEALs, as Obama told the press after the operation, which provided insight into al-Qaeda’s activities and proves that bin Laden is still “within the network” played an important operational role ”.

According to Hersh, the burial at sea never took place, as two long-time advisors to US special forces would have confirmed. One of the two told him that the killing of bin Laden was “political theater to polish up Obama's military credibility ... Bin Laden became a working tool.” The other reported that he was flying over the mountains of the US military airfield in Jalalabad, Afghanistan Hindu Kush bin Laden's body parts, including his head, which had "only a few bullet holes", were thrown from the helicopter. Because according to the legend constructed before the operation, it was agreed between the ISI and the CIA that bin Laden was killed in a drone attack in the Hindu Kush on the Afghan side of the border. However, after the helicopter crash, the question of the whereabouts of the corpse and thus another cover-up story was invented, which then included the burial at sea.

In his article, Hersh quoted Carlotta Gall , Afghanistan and Pakistan correspondent for the New York Times for almost twelve years , who wrote in 2014 that the ISI knew of Bin Laden's whereabouts. Gall wrote, referring to Hersh's article in the LBR: “Hersh's scenario explains a detail about the night bin Laden died that has always puzzled me. When one of the helicopters crashed, calls were received by the Abbottabad police. They could have been there within minutes - but were called back by the army. So it happened that the Seals were able to stay undisturbed in the property for 40 minutes until a reserve helicopter arrived. Only then did the army show up. ”And Hersh referred in his article to Imtiaz Gul, a Pakistani security expert and head of the think tanks Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS) in Islamabad , who in his book The Most Dangerous Place, and Pakistan: Before and After Osama bin Laden had already published in 2012 that four agents had informed him that the Pakistani military knew about the US operation in advance. Hersh finally quoted the former head of the ISI, General Asad Durrani : "What you are telling me is basically what I have heard from previous colleagues who have dealt with the matter".

The "biggest lie" for Hersh was that General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani , head of the Pakistani army at the time , and General Ahmed Shuja Pasha , head of the ISI , had not been informed. Seymour Hersh summarized at the end of his article: "Lying at the highest level remains the modus operandi of US politics, including secret prisons, drone attacks, night operations by US special forces, evasion of official channels and the exclusion of those who say no."

Central points of the portrayal of Hersh had already been published in 2011 in the blog of Raelynn Hillhouse , a former professor of political science and "intelligence expert ", based on other sources. She also sticks to her statements and adds that her sources differ from those of Hersh. And in Germany, too, the Pakistan expert Hein G. Kiessling wrote in a book back in 2011 that “The Americans' Abbottabad Operation [...], even if officially different declarations come from Washington and Islamabad, most likely after prior agreements of the CIA with the ISI leadership ”. The BND also assumed that a small circle within the ISI had knowledge of Bin Laden's presence in Abbottabad. Carlotta Gall also wrote that he had learned from credible sources "that it was actually a Pakistani army officer ... who told the CIA where bin Ladin was hiding." Part of Hersh's report was also supported by NBC . Two intelligence sources had confirmed the version of the "walk-in", ie the disclosure of the informant about the bin Laden's hiding place, to the CIA employee at the US embassy. This report was later corrected so that the defector was just one of several sources that led to the capture of bin Laden. In an interview on a radio show on KPFK Pacifica Radio hosted by Ian Masters, Middle East expert Robert Baer found the Hersh story plausible and gave it substantial credibility. Former CIA officer Philip Giraldi claims in The American Conservative magazine that Hersh's account is credible.

Reception and criticism of the “The Killing of Osama Bin Laden” report

The publication of the report was rejected by several US media outlets because of serious concerns. The White House, Pentagon and National Security Agency responded on May 11 with denials of Hersh's allegations. Obama's spokesman, Josh Earnest , dismissed Hersh's account as an "article riddled with inaccuracies and blatant untruths," and National Security Council vice spokesman Edward Price said it contained "too many baseless allegations to investigate in detail" . Former CIA deputy and acting director Michael Morell said Hersh's source has no idea what she's talking about and of the journalist's allegations: "Every sentence I've read is wrong." Former CIA spokesman Bill Harlow said ; Hersh's report "makes absolutely no sense." Journalist Jon Schwarz states in an article for The Intercept that Bill Harlow remained unquestioned for his statement about Hersh, given Harlow's own statements about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq in 2003. Rob O'Neill, a former Navy Seal who claims to have shot bin Laden also contradicted Hersh's account in an interview with Fox News .

The bin Laden expert Peter Bergen described Hersh's version as a "mishmash of nonsense". When asked about Bergen, Hersh replied: “The media quote him. He sees himself as the trustee of all bin Laden affairs. "

To observers, Hersh's publication appeared as if an aging investigative journalist had “lost touch with reality”. The publication was commented with "mockery and mockery". Paul Middelhoff wrote in the Tagesspiegel that Hersh was fighting for his credibility and that this was once again at stake because he had "repeatedly [...] but also got into untenable accusations". Critics complain about Hersh's report that it essentially refers to “the one secret service employee” who wants to remain anonymous. Although named sources would not contradict the version, there was no concrete evidence or documents to support Hersh's account. Ansgar Graw and Uwe Schmitt drew the conclusion in Die Welt shortly after publication: "Seymour Hersh will have to provide more evidence in his book than he did in his essay."

Trevor Timm , a co-founder of the Freedom of the Press Foundation , analyzed media coverage of Hersh's claims in the Columbia Journalism Review , calling them infamous. Instead of doing additional research to either corroborate or disprove the details of Hersh's account, the media coverage is mainly aimed at attacking the messenger.

On June 17, 2015, BBC 2 broadcast a 30-minute program entitled The Bin Laden Conspiracy? by Jane Corbin , an investigative documentary that investigated evidence of conspiracy theories surrounding Bin Laden's death. Hersh's allegations were examined in more detail. Tim Dowling believes that the documentation does not provide an answer as to which version is the right one.

2017 poison gas attack in Syria

On June 25, 2017, Die Welt am Sonntag and Welt Online published an article by Seymour Hersh, in which the latter claimed that the poison gas attack on the Syrian city of Khan Shaichun on April 4, 2017, which killed more than 80 people, was not caused by the poison gas Sarin , but caused by the explosion of a chemical warehouse as a result of a bombing by the Syrian Air Force. This representation and its publication by the world was criticized and questioned by several media shortly after it was published.

For example, Stefan Schaaf criticized in the taz that Hersh relied on very few sources for his allegations, all of which remained anonymous. In addition, the facts presented are extremely thin, lack concrete evidence and oppose a large number of concrete and well-documented observations and evidence. Since this has also been the case for other Hersh publications in recent years, his texts have now been consistently rejected by the established media, which had already seriously damaged Hersh's credibility. Schaaf therefore specifically accused the world of providing a platform for Hersh's ill-founded allegations without Hersh being able to provide a single verifiable source.

In the fact finder of Tagesschau.de , Nele Pasch and Wolfgang Wichmann accused Hersh of ignoring a large number of detailed reports, all of which had provided evidence of sarin or a similar chemical warfare agent from direct samples. In addition, he would reinterpret similar results from other reports without his own knowledge of the facts in order to incorporate them into his own narrative. Pasch and Wichmann also emphasize how alone Hersh is with his view of things, also with regard to previous dubious publications, and how questionable their publication by the world is consequently.

Eliot Higgins of the investigative platform Bellingcat also stated in a series of publications on Hersh's article that both his own arguments and those of the alleged experts on whom he relies were full of errors and discrepancies and could not be upheld. Thus, after his unfounded statements on the poison gas attack in Ghouta on August 21, 2013, he would ignore elementary facts for the second time and make false claims, all of which only based on anonymous and non-verifiable sources. He accuses the world of not taking a position on the allegations, despite the overwhelming facts, and of not publishing any rectification. This silence would help spread Hersh's falsehoods from propaganda websites and conspiracy theorists.

Two investigations by the UN Human Rights Council as well as the joint investigation mission of the United Nations and the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons also showed with certainty that the government of Bashar al-Assad was responsible for the poison gas attack in Khan Sheikhun and that it had used sarin in an air strike . Alternative theories to the attack that were published by Seymour Hersh and the world are thereby refuted and no longer tenable.

Elliot Higgins commented in Newsweek in February 2018 that the OPCW report on the Khan Sheikhun attack showed that Hersh's version was made up in such a way that not even Russians and Syrians picked it up. Hersh himself replied to the criticism that he had learned to write what he knew and then did not care.

Journalistic working style

Hersh was inspired by the work of Carl Sandburg , Arthur Schlesinger , Pulitzer Prize winner David Halberstam and the icon of investigative journalism in the USA, Izzy Stone .

At the City News Bureau of Chicago, Hersh learned the trade of interviewing witnesses, extracting facts, verifying and "correctly" reproducing them; this according to the specifications of editor-in-chief Arnold Dornfeld: "Don't tell me what you think - tell me what you know". The thorough research required here was a lifelong lesson and the most important tool in later controversies. However, at CBS he also acquired questionable journalistic methods to get information, such as pretending to be a different person. At United Press International , Hersh found access to investigative journalism. UPI's motto was: "Do it quickly, do it right, make it understandable." He followed Izzy Stone's principle: "You can't write without reading." Deception, exaggeration and bluffing expanded his repertoire. His responsibility at the Associated Press for shortening articles so that they could be read out as radio news shaped his condensed style of reporting. At AP he got to know the " establishment journalism" according to the AP motto: "Accuracy, impartiality and integrity." Objectivity in reporting, as it has been strongly demanded since the 1950s, Hersh disregarded, which he often did with his editors offended. He was still not considered a "sinner" because his stories always had a profile and were "balanced on the knife edge." Over time, Hersh collected material and articles. This comprehensive collection of reports and documentation is the basis of his research, such as his revelations about the CIA. Access to stories told by soldiers is the key to good war coverage. He did not leave the country to do research, but sought out soldiers returning home.

Hersh's main means of getting information is through the telephone. His phone style is relentless, dynamic, deceptive, intimidating. He is notorious for his quick talk. Bill Kovack, editor at the New York Times, commented, "In Sy's hands, a phone was an improvised explosive device."

Hersh built a large network of anonymous informants, particularly non-conformist people and officials who have been retired. Since his notoriety rose, he was also contacted directly by sources. The use of anonymous sources became one of his trademarks. His passions are baseball, poker and golf, with which he maintains his contacts.

Characteristics of Hersh

According to historian James Boylan, Hersh led the way in a journalism that "got out of control" in the mid-1970s. The biographer Robert Miraldi describes Hersh as friendly but aloof, cheeky, passionate, obsessed, rough, productive, successful and downright controversial. Together with his rival Bob Woodward , he is certainly America's best-known investigative journalist. Thomas Powers commented: "If a pantheon of American journalism were to be established, Hersh would be in it."

criticism

Numerous people were damaged in their public reputations by Hersh, such as John Lavelle, Ed Korry, Henry Kissinger , Manuel Noriega and Dick Cheney . He was hostile to six US administrations from Lyndon B. Johnson to Barack Obama. “There has never been a president who liked me. I take it as a compliment, ”said Hersh in an interview. He also exposed spies like James Jesus Angleton in the course of his CIA revelations. Critics see Hersh as a personality assassin, a politically left-wing and unreliable journalist and anti-Semite . Death threats were made against him . His family life is therefore a private matter for Hersh. Hersh's biographer Robert Miraldi notes that critics wrote articles about “King Sy's” mistakes and others about his delusions. One reviewer said Hersh made offbeat allegations but did not write them down. Bill Arkin said, "He can have any fact wrong, but the story is correct."

Use of anonymous sources

There has been ongoing criticism of Hersh's use of anonymous informants. Critics like Edward Jay Epstein and Amir Taheri say he over-trusts their statements. For example, Taheri describes in his reception of Chain of Command : “As soon as [Hersh] makes an allegation, he cites a source to support it. In any case, it is either an unnamed former official or an unidentified secret document that came to him under unexplained circumstances [...] According to my count, Hersh has anonymous sources in 30 foreign governments and almost everywhere in US government agencies. "

The New Yorker editor David Remnick said he knew the identity of any unnamed sources Hersh. This is what he told the Columbia Journalism Review . He explains: "I know every single source in his work [...] every retired intelligence worker, every general with a reason to know him, [...] I ask [Hersh]: 'Who is this?" What is his interest. ' And we'll talk it through. "

Talk

In an interview for New York Magazine , Hersh made the distinction between standards and strict objectivity for his printed work. He leaves room for maneuver in which he speaks unofficially about stories that are still in progress, and blurs them to protect his sources. “Sometimes I change events, times and places in the best possible way to protect people [...] I can't tweak what I'm writing. But of course I can make up what I say. "

Awards (selection)

- 1970: Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting

- 1969: George Polk Award (as well as 1973, 1974, 1981, 2004)

- 2005: Prize for the freedom and future of the media from the Media Foundation of the Sparkasse Leipzig

- 2005: The Ridenhour Courage Prize

- 2017: Sam Adams Award for Integrity

Works (selection)

- Chemical and Biological Warfare: America's Hidden Arsenal . Anchor Books, Garden City 1968

- My Lai 4: A Report on the Massacre and Its Aftermath . Random House, 1970

- Cover-Up: The Army's Secret Investigation of the Massacre at My Lai . Random House, 1972

- The Price of Power: Kissinger in the Nixon White House . Simon & Schuster, 1983

- The Target Is Destroyed: What Really Happened to Flight 007 and What America Knew About It . Random House, 1986

- The Samson Option: Israel's Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy . Random House, 1991 (German nuclear power Israel. The secret potential for annihilation in the Middle East . Droemer Knaur, 2000)

- The Dark Side of Camelot . Little, Brown & Company, 1997 ( Kennedy: the end of a legend )

- Against All Enemies: Gulf War Syndrome, the War Between America's Ailing Veterans and Their Government . Ballantine Books, 2000

- Chain of Command: The Road from 9/11 to Abu Ghraib . HarperCollins, 2004. (Eng. The chain of command. From September 11th to Abu Ghraib . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2004; review )

- Foreword in: Robert Baer : See No Evil: The True Story of a Ground Soldier in the CIA's War on Terrorism . 2003

- with Scott Ritter : Iraq Confidential: The Untold Story of the Intelligence Conspiracy to Undermine the UN and Overthrow Saddam Hussein . Nation Books 2005

- The Killing of Osama Bin Laden . Verso 2016.

Essays, articles, reports (selection)

- The general's report. How Antonio Taguba, who was investigating the Abu Ghraib scandal, became one of his victims . Sheets for German and International Politics 8/2007, pp. 937–956

- Reporters in Washington. Vietnam, Iraq, Iran - The Power and Impotence of Journalists , In: Lettre International , LI 80, spring 2008.

- Red line, rat line. Poison gas, civil war and war - Obama, Erdoğan and Syria's rebels , In: Lettre International , LI 105, summer 2014.

- The death of Osama bin Laden. Lies, Logic, Facts - A Critical Reconstruction of Events , In: Lettre International , LI 109, Summer 2015.

Books on Hersh

Autobiography

- Seymour M. Hersh: Reporter: A Memoir . Alfred A. Knopf, USA, New York 2018, ISBN 978-0-307-26395-7 (English).

Biographies

- Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh: Scoop Artist . University of Nebraska Press, USA, Potomac 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 (English).

- Oliver Burkeman: Scoopht . The Guardian , Manchester October 9, 2014 (English, theguardian.com ).

Related to Hersh

- Kathryn Signe Olmsted: Challenging The Secret Government . the post-Watergate investigations of the CIA and FBI. University of North Carolina Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8078-2254-X (English, limited preview in Google Book Search - Ph.D. dissertation: Challenging The Secret Government: Congress And The Press Investigate The Intelligence Community, 1974–1976 . University of California at Davis, 1993, AAT 9328863).

Web links

- Literature by and about Seymour Hersh in the catalog of the German National Library

- Seymour Hersh in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Thomas Leif: There is always an ex-wife. In: The daily newspaper . December 26, 2010, accessed December 27, 2010 (detailed interview with Seymour Hersh about investigative journalism).

- Literature list from un to Seymour Hersh as of November 13, 2007

- Article by Seymour Hersh in the New Yorker newspaper (1971-2015)

- Transcript: Jane Wallace Interviews Seymour Hersh (PBS, February 21, 2003)

- David Rubien, Seymour Hersh ( Memento from September 23, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) - The man who broke the story of Vietnam's My Lai massacre is still the hardest-working muckraker in the journalism business. (Salon.com, Jan 18, 2000)

- The general's report. How Antonio Taguba, who investigated the Abu Ghraib scandal, became one of his victims (" Blätter für deutsche und Internationale Politik ", 8/2007)

- “The fragility of democracy. Acceptance speech by Seymour M. Hersh " for the award of the" Democracy Prize 2007 "of the papers for German and international politics .

- Susanne Hofmann: Reporter legend Seymour Hersh - thorn in the flesh of the mighty Bavarians 2 radio knowledge . Broadcast on January 28, 2021 (podcast)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 45, 273 f . (English).

- ↑ Unknown: Seymour Hersh Biography. Internet Movie Database, May 20, 2015, accessed May 19, 2015 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Bernhard A. Drew: 100 most popular nonfiction authors: biographical sketches and bibliographies . Libraries Unlimited (Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.), Westport, USA 2008, ISBN 978-1-59158-487-2 , pp. 166–168 ( limited preview in Google Book Search - eng).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 274 (English).

- ↑ Jeff Wallenfeldt: Seymour Hersh. Encyclopædia Britannica , Inc., May 13, 2015, accessed May 20, 2015 .

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 351 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 55 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 57 f . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 59 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 60 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 67 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 66 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 70 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 72, 74 f . (English).

- ↑ a b Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 76 ff . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 78 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 79 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 80 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 86 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 88 f . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 100 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 12 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 2 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 90 (English).

- ↑ a b c d e f Investigating Power: Seymour Hersh: Career Timeline. 2011, accessed May 19, 2015 .

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 90 ff . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 95-97 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 28, 122 f . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 28, 123 (English).

- ↑ Seymour Hersh - The man who broke the story of Vietnam's My Lai massacre is still the hardest-working muckraker in the journalism business. ( Memento from January 30, 2011 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 1 f . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 3 ff., 23 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 7th ff . (English).

- ↑ a b Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 9 ff . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 15th f . (English).

- ↑ Calley was drunk while Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 13 (English).

- ↑ a b c Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 16 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 17 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 18 (English).

- ^ Seymour M. Harsh: The Scene of the Crime. In: The New Yorker. The New Yorker, March 23, 2015, accessed May 11, 2019 .

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 19 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 22 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 25-27 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 31 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 29 f . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 34 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 35 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 37 f . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 28 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 39 f., 41 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 40, 42 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 35 f . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 44 (English).

- ^ Seymour M. Hersh: The Scene of the Crime. The New Yorker online, March 30, 2015, accessed May 19, 2015 .

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 40 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 42 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 132,216,234 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 132-135 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 135 f . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 141-143 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 138 (English).

- ^ John Simkin: Alfred W. McCoy. Spartacus Educational, September 1997, accessed June 23, 2015 (updated August 2014).

- ↑ a b c Timothy S. Hardy: INTELLIGENCE REFORM IN THE MID-1970s. Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, accessed June 23, 2015 (APPROVED FOR RELEASE 1994, CIA HISTORICAL REVIEW PROGRAM, 2 JULY 96).

- ↑ a b Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 150 ff . (English).

- ↑ Timothy S. Hardy: INTELLIGENCE REFORM IN THE MID-1970s. Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency, accessed on June 23, 2015 (English, APPROVED FOR RELEASE 1994, CIA HISTORICAL REVIEW PROGRAM, 2 JULY 96): “Yet Hersh may not even merit a historical footnote, perhaps, because the ball he started rolling never really knocked down all, or even any, of the pins. The ending of the Post dynamic duo's story, after all, was the resignation of a reigning President. "

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 160, 165 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 160 f . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 163 f . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 165 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 167 f . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 169 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 171 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 176-178 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 179, 181 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 182 f . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 174, 155, 188 (English).

- ^ Seymour Hersh: Huge CIA operation reported in US against antiwar forces, other dissidents in Nixon years. (PDF) New York Times , December 22, 1974, accessed June 20, 2015 (Reproduced by permission of copy right holder; further reproduction prohibited.).

- ^ Karen DeYoung, Walter Pincus: CIA to Air Decades of Its Dirty Laundry. Washington Post , June 22, 2007, accessed June 20, 2015 .

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 187, 191 f . (English).

- ↑ Thomas Blanton: The CIA's Family Jewels. In: Electronic Briefing Book No. 222 National Security Archive , June 21, 2007, accessed June 20, 2015 (Update: June 26, 2007).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 190 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 193-195 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 195 f . (English).

- ↑ a b Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 192 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 197 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 197 (Eng., Quote: “ Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger actually told his newsroom to stop saying the paper had hired investigative reporters.“ All reporters should be ›investigative reporters‹ for whatever that means ”,“ he wrote.).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 201 ff . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 206 (English).

- ^ William Burr: Document Friday: The Origins of "Glomar" Declassified. The National Security Archive, June 15, 2012, accessed May 19, 2015 (eng, Project Azorian The CIA's Declassified History of the Glomar Explorer , Memorandum of Conversation, "[Jennifer?]" Meeting , March 19, 1975 ).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 221, 217-223 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 224 (English).

- ↑ Mark Ames: Seymour Hersh and the dangers of corporate muckraking. pando.com, May 28, 2015, accessed June 24, 2015 .

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 176, 235, 245 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 237, 240 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 242 f . (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 258 (English).

- ↑ Robert Miraldi: Seymour Hersh. Scoop Artist . 1st edition. Potomac Books, University of Nebraska, Nebraska 2013, ISBN 978-1-61234-475-1 , pp. 247-252 (English).