Wiener Neustädter Canal

The Wiener Neustädter Canal is an artificial watercourse that was put into operation in the Archduchy of Austria under the Enns in 1803 and extended to 63 km in length , on which mainly wood, bricks and coal were transported from the area south of the Danube to Vienna . Since later, private owners primarily pursued railway projects and reallocated important parts of the waterway to the railway line, canal shipping declined sharply from 1879 and ceased completely before the First World War.

The drainage of the watercourse operated by these owners between the world wars was partially averted by those authorized to use the canal water, until after the Second World War the state of Lower Austria took over the majority of the watercourse, which was shortened to 36 km and gave it a new main function as a recreational area. In much of the rest is available as a monument under monument protection .

The history of the waterway

The history

In 1761, the 23-kilometer Bridgewater Canal was opened in north-west England , connecting Sir Francis Egerton's coal mine with Manchester . While two horses could only move two tons on the road, one horse was enough to bring a boat filled with 30 tons of coal to its destination at the same speed. It wasn't long before the new means of transport brought the price of coal in the target area down by almost two thirds. This spurred the local industrial development to such an extent that the city was given the exemplary function that was supposed to show its darker side in “ Manchester capitalism ”.

In the Austrian Empire, shaken by permanent wars , a similar revolution was still a long way off. They had only just begun to compensate for the loss of the Silesian industrial areas that fell to Prussia in the Seven Years' War by promoting industry in Vienna and in southern Lower Austria. When these measures began to take effect in the last third of the 18th century, they soon showed their downsides. The high energy demand in this region, which was mainly met by wood or charcoal well into the 19th century, drove up the prices of these products on the one hand, and on the other hand the lucrative demand coverage led to overexploitation of the forests, which initially did not legal barriers were set. In 1803 the travel writer Joseph August Schultes wrote in one of his hiking reports about the range of hills in the foothills of the Alps in front of him:

- “They have been cut down from the summit to the foot, no trunk has been spared from the murderous ax to give the forest the opportunity to rejuvenate itself. What a forest scandal to drive away mountains completely ... This sad prospect of the future can be found almost in all mountains in Lower Austria in stately forests. "

All attempts to establish mineral coal as the main energy supplier following the British example were initially unsuccessful, despite state subsidies (distribution of free coal, exemption of coal from customs duties and taxes). Still convinced of the future of coal, Anton David Steiger founded the “Wiener Neustädter Steinkohlengewerkschaft” together with dignitaries of the statutory city of Wiener Neustadt in October 1791. The coal mine on the Brennberg , owned by the royal Hungarian free city of Ödenburg (Sopron) , was leased under disastrous conditions (virtually unlimited coal deliveries to the citizens of the city at prices that should not prove to be cost-covering) and mining began, due to the lack of experienced Miners and a lack of sales made slow progress at first. The company became more dynamic when Bernhard von Tschoffen , Joseph Reitter and Count Apponyi joined the company, took them over and acquired additional mining rights for hard coal in the Wiener Neustadt area. There were customers in the local area, but hardly in Vienna because of the expensive transport.

In order to make the transport of goods from southern Lower Austria to Vienna more efficient, in 1794, on Tschoffen's advice, the company presented Emperor Franz II with a plan to build a shipping canal. Emperor Franz II sent one of his officers of genius , the engineer lieutenant colonel Sebastian von Maillard, on a detailed investigation. After his positive report, the emperor sent him to England with Tschoffen to study canals there. Impressed by the high economic efficiency of these facilities, Franz II granted the applicants by court decree in July 1796 permission to build a canal to the Adriatic Sea .

The "kk privileged Steinkohlen- & Canalbau AG" was founded, which initially only aimed at building the canal from Vienna to Ödenburg or Raab (Győr). A quarter of the estimated 2 million guilders came from the "trade unionists" and the emperor, the rest could be raised through share sales. The company appointed Maillard "director of the hydraulic company" and entrusted him with the preparation of the plans and the construction management. His most important employees were Captain Swoboda, professor at the Theresian Military Academy , and engineer Josef Schemerl , at that time regional construction director for Krain . While Swoboda was laying the route to Ödenburg, Maillard and Schemerl devoted himself to the more difficult route work towards the Adriatic via Ljubljana . At Oberlaibach ( Vrhnika ), however, according to Maillard, the limit of what was technically feasible at the time had been reached. Maillard:

- "Since finally nothing but bare, porous rocks consisting of many cavities were encountered on the rest of the way from Oberlaubach to Trieste, no canal can be made on this route."

The construction of the canal (1797–1803)

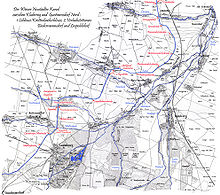

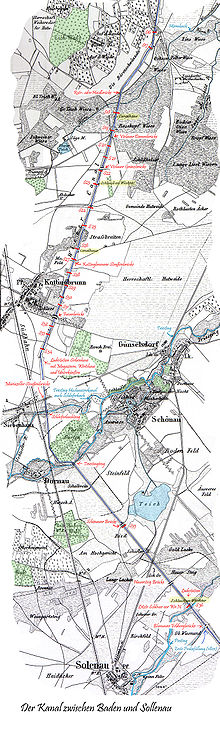

After the alignment, the purchase of land, the leasing of quarries , brick and lime kilns in the Guntramsdorf and Mannersdorf area and an iron smelter in Pitten , the implementation of the plans began on June 19, 1797. It should be more difficult than a quick glance at the map of the Vienna Basin would suggest. This basin is by no means shallow, rather it has a height difference of 200 meters over 60 km from Neunkirchen to the Danube, which is considerable for canals. In addition, the route could not follow the course of the valley, but was faced with the task of crossing numerous small but high watercourses. In addition, there was the often extremely water-permeable subsoil, which required complex sealing measures. The main problem, however, was and remained the lack of water, which, in addition to a complex feed system, forced a narrow canal, small lock chambers and thus small barges, which should make the waterway less competitive in the medium term.

The first 48 civilian workers who were not employed in a specific field left the workplace very soon. They were replaced on July 8 by 100, later 200 soldiers. The slow construction progress criticized by the Emperor on October 26th led to the assignment of 1260 construction soldiers the following year. However, the storm of August 20, 1798 destroyed much of their work.

When these soldiers were withdrawn in 1799 in the course of another campaign against Napoleon , they were replaced by convicts, with the difficult cases having to work in chains. This war-related shortage of labor, storm damage and the inflationary development in construction costs hampered construction progress and led to tensions between construction management and financiers. The sewer company, which in 1799 merged with the “ Innerberger Hauptgewerkschaft ” to form the “kk privileged Hauptgewerkschaft” (kk privileged main union), ultimately attributed these conditions to the mistakes of the site manager Maillard. The court commission (chaired by Count Saurau ) intervened. Construction planning (Maillard) was separated from construction ( Joseph Schemerl von Leythenbach ) and on August 27, 1798 Maillard was asked to submit a general plan. Despite fulfilling requirements, the shareholders parted from the site manager in 1799 without any clearance. The fact that Maillard received 8,000 guilders (officially for his children) from the emperor and was promoted by him in the following years as head of the imperial genius (pioneer) troops to field marshal may serve as proof that his reputation at least at court had not suffered.

Nominated as site manager on October 1, 1799, Joseph Schemerl also had to accept convicts on the construction sites the following year. Locking the objections of the barons Brown and Moser had an impact in this building season, resulting in Schonau an der Triesting initially refused to cede land for the canal construction and were able to round enforce route changes to a pheasant garden.

In 1801, Count Rottenhan took over the canal committee of the court chamber . After inspecting the finished sections, he ordered straightening of the route and renewed the Liesing aqueduct , which was in danger of collapsing . From May 1, 1801, he was able to provide the site manager with a few hundred pioneers for renovation and further construction, with whom the work proceeded rapidly for the first time under the direction of four additional engineers. Since the court chamber had to pay for the cost of this renovation work again, Rottenhan endeavored to take over the canal in its entirety. He succeeded in using the disagreements within the new "main union" to reverse the merger that took place in 1799 and, after tough negotiations, to pay off Tschoffen, Graf Apponyi and Reitter, which was sealed on April 13, 1802.

As one 1801 - still without feed water - had reached Wiener Neustadt, the impatient Schemerl for testing led the Piesting one. This could only be done for 24 hours at a time, as the stucco (artillery) boring mill in Ebergassing, which was important for the war effort, was dependent on this water . After all, the test water reached the outskirts of Vienna to the north, and in an attempt to the south it seeped away after just a few kilometers. In order to counteract the “seizure” (seepage), Schemerl had the channel bed “pod” in the area of the water-permeable pebble layers. After the canal bed had been plowed up, a mixture of two-thirds of pebbles and one-third of earth was brought in and compacted by riding horses.

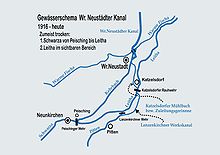

In order to finally have permanent water to fill the canal, the canal was led in 1802 from Wiener Neustadt in the direction of Pöttsching to over the Leitha into the Heutal, where the Leitha water diverted in the then Hungarian Neudörfl could flow into the canal via the "Neudörfler Rigole " (see sketch 8). . To protect against siltation and flooding, a large sludge settling basin was created just before the feed into the canal and a flood canal was led to the Leitha immediately after the Hungarian border.

The longer test fillings from 1802 to spring 1803 revealed further sealing defects, this time not only affecting the building itself, but also the residents. Water from broken dams and leaking canal parts, swamped fields and meadows, contaminated local wells, penetrated basements and put buildings at risk of collapse. The coffins floated in the Franciscan crypt in Maria Lanzendorf . In addition, on July 29, 1803, another bad storm occurred in which the Peischinger weir was torn away from the Schwarza and the Kehrbach and the “Neudörfler Rigole” were filled with gravel and mud. The damage from canal water and storms not only delayed completion, they also resulted in lengthy and costly legal proceedings, which helped to increase the construction costs calculated by Maillard from two million to over 11 million guilders.

Operation until the official cessation of shipping operations (1803–1879)

The canal operation under state administration (1803-1822)

At the beginning of March 1803, the slow filling of the entire canal began. Until March 15, the canal sections between the locks, called “positions”, were stretched to Lanzendorf ; on March 29th, the churchyard lock at Sankt Marx on Wiener Linienwall was opened. However, before the first water could reach the Vienna harbor, a dam broke near Simmering , which took six weeks to repair. As a result, the first official inspection of the “Canal Construction Court Commission”, which was scheduled for mid-April, had to begin at the churchyard lock on the outskirts of Vienna. This trip lasted from April 18th to the evening of April 21st. The main reason for the slow pace was the enthusiasm of the population in the neighboring communities.

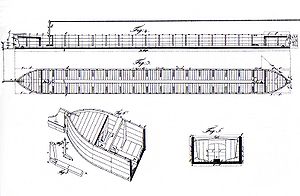

The watercraft were replicas of the British narrowboats . They had a length of 22.8 m and a width of 2.05 m and were manufactured in Wiener Neustadt (shipyard see sketch 8) and Passau . Due to their symmetrical construction, they did not have to be turned at the target point; only the rudder and the rod for the cable were repositioned. The crew of a tow train consisted of three men who took turns in their functions. The boat, steered by the helmsman, pulled a horse, which was led by the horse guide (" towler ") along the towing or towing path that ran along the east bank and below the bridges. Incoming traffic was grained at almost four kilometers per hour, the empty ship or the downhill ship had to avoid. Since there was only one stairway, oncoming traffic and overtaking were associated with some rope maneuvers (see picture). Due to the low current in the reaches, the carts had to be pulled in both directions. The route from Vienna to Wiener Neustadt took an average of one and a half days. At night, the canal was idle, and the boatmen had berths in the "canal houses". The shipping operations ran from the beginning of April to the end of October, the remaining frost-free time was used for maintenance and repair work. To this end , the canal was largely drained.

Freight operations started on May 12, 1803; due to delays in delivery of the barges, it did not start at 16, but only with four ships. During the first filling of the sections between the Kirchhofschleuse and the Port of Vienna, the already well-known leakage problems arose, which could also only be resolved with careful “podding”. Since Schemerl had estimated 1803 as a mere trial year, he was satisfied with an initial balance of 400 freight trips. In the spring of 1804 the transport was able to start with 55 ships, but there was another dam breach, this time at the churchyard lock and immediately after the damage was repaired, another canal blockage due to the washing of some buildings at the line office and the contamination of wells, which reduced the traffic between the Krottenbach and the Port of Vienna for a further six weeks. The balance of the second year of operation was 1,713 shiploads, half of which were only brick transports from Guntramsdorf to Vienna.

The third year of operation (1805) began with the third severe weather disaster. A sudden thaw caused the rivers and streams in the Alpine foothills to swell. Fischa and Piesting united in the Steinfeld north of Wiener Neustadt and tore up the canal embankment between Lichtenwörth and the Untereggendorfer Bridge, at the same time the Kehrbach brought again large amounts of sludge into the Neustädter Hafen. The war against Napoleon was devastating in other ways. On August 14, 1805, the experienced boathands from northern Germany were thrown into battle so quickly that there was not even time to bring the barges to their destination. In order to avoid liability claims by customers, a poorly trained replacement was used, which caused some damage, but with the help of which the annual balance of this disaster year could still be increased to 2,103 trips and 42,000 tons of freight. In 1806 the operation was still in the hands of these amateurs, but this had less of an adverse effect than the poor condition of the locks, from which the cheap brick locks began to crumble. During the renovation, they were widened by a foot (32 cm), which enabled the use of 2.30 m wide barges with a significantly higher loading capacity. In 1807 experienced “pontoniers” came to the canal again, but in 1809 they too had to take up arms again. Since the Napoleonic troops were also advancing south during this campaign, the company was directly affected this time. After the shipments and warehouses were looted, the canal houses were occupied and the ships were confiscated, canal operations came to a complete standstill during the first months of the occupation.

In 1810, the “Canalfonds” received the funds to continue building the route from the confluence of the Neudörfler trench to the Pöttschinger Sattel. This 3.8 km long section of the route was built by 500 soldiers between August 1 and December 15, 1810 and went into operation in the spring of 1811. The continuation to the coal mines near Ödenburg, which is so important for profitability, failed due to the resistance of the Hungarian landowners, which even a personal intervention by the emperor could not break. It was feared that there would be a drop in sales in horse breeding - after all, 40,000 horses were traveling between Vienna and Trieste every day - as well as cheap imports of agricultural products and the impairment of the mills around Ödenburg due to the deprivation of the scarce water available. In addition, there were the political relations between the imperial family and the Hungarians, which were by no means unclouded, and which were to deteriorate considerably after the brutally suppressed revolution of 1848 . This meant that the plans to continue the canal via Ödenburg to Raab or even Trieste were to be regarded as having failed. The Pöttschingen canal branch was soon shut down again for nine years due to a lack of freight and only reactivated under the tenant Fries.

After three well-balanced years, the state-owned operating company fell again in the red in 1815. The mining industry remained a source of losses, and urgent repairs to the locks drained profits. In addition, there were extensive acts of fraud by imperial officials. On May 11, 1819, Minister Graf Stadion therefore proposed that the court chamber should limit itself to maintaining the structure and possibly continuing the route, but leasing the shipping operations themselves.

The canal under the lease of the Fries bank, under Matthias Feldmüller and Georg von Sina (1822–1846)

When the Fries bank suggested that the Hofkammer take over the lease in 1822, an agreement was reached relatively quickly. The contract was concluded on May 14, 1822 for twelve years. The annual rent was set at 6,000 guilders and should only be increased to 12,000 guilders after the canal was extended to Ödenburg. In addition, the tenant had to undertake not only to pay for the costs of all repair work, but also to build two large objects (locks, aqueducts) each year, which should add up to a multiple of the rent. Furthermore, Fries felt compelled to enter into the long-term contracts with Count Hoyos (wood transport on his own), the wagon entrepreneur Neilreich, the brick kiln leaseholder Gansterer and the shipbuilding leaseholder Ledl. In view of the high creditworthiness of Moritz Reichsgraf von Fries - he was considered the richest Austrian - the court refrained from providing a deposit. The first annual report of the court chamber on the conduct of the "Niederösterreichische Schiffahrtskanal-Lachtungsgesellschaft" was extremely positive. In addition to the ongoing repairs, the company had produced several larger objects, put the stretch from Wiener Neustadt to Pöttschinger Sattel, which had not been used for nine years, back into operation and spent a total of 27,000 guilders on it. The negotiations regarding the further construction of the waterway in the direction of Ödenburg, which Fries had led with Prince Nikolaus II Esterházy and the Ödenburger Obergespan (head of the county administration), were unsuccessful. Although the emperor himself had failed because of this problem, Fries had to fear that he would lose the lease because he could not start construction in the direction of Ödenburg within the contractually agreed six years - the court chamber refused to extend the deadline. But before this could happen, Fries slipped into bankruptcy for other reasons.

Since the bankruptcy administration of the bank was able to win over the timber merchant Matthias Feldmüller Junior, son of the shipmaster and "Danube general" Matthias Feldmüller as a sub-tenant from March 1, 1827, it was able to continue to transfer the lease payments and the court chamber's application for restitution of the canal to reject. Feldmüller's father was a highly respected businessman, also at court, who had acquired his fortune as a transport company on the Danube during the Turkish wars and was operating 1,225 Danube ships at the time the lease was taken over. When the deadline for further construction of the canal passed without construction work, the court chamber put the lease out to tender again. Feldmüller Junior was awarded the contract for the period from January 1, 1829 to the end of 1834. The lease schilling remained the same, apart from the repairs, only one large object had to be rebuilt each year, and the obligation to continue building was no longer included. However, should an entrepreneur or a company be found to continue the canal through a canal or a railway , the tenant was not allowed to "create an obstacle". Although Feldmüller invested a lot in the canal, which put it in better condition than ever before, he was the first tenant to make permanent profits from the company.

At the auction of the lease on September 17, 1834, Baron Georg Freiherr von Sina , the owner of a large bank, was awarded the contract for 13,085 guilders annually until 1846, with a deposit of 12,000 guilders. Although Sina by no means neglected the canal, for him it was primarily a means to another end. Since he saw the future of transport more on the railroad, he expected an exemplary canal lease to provide a better starting point for his rail projects from Vienna to the south and east. On February 16, 1839, Sina actually succeeded in obtaining the concession for the northernmost section of the southern railway , the Vienna - Wiener Neustadt - Gloggnitz railway . For construction and operation he founded the "kkprivilegierte Südbahngesellschaft", the first train on the Vienna - Gloggnitz route ran on May 5, 1842. On June 6, 1840, he also succeeded in obtaining the concession for the Wiener Neustadt - Ödenburg route, which went into operation in 1847. The construction manager for both railway constructions was Matthias Schönerer , who had already built the Budweis – Linz – Gmunden horse-drawn railway , which had been in operation since 1832 , for Sina and the like . Sina was not spared from sewer problems either. First of all, the coal storage area for the construction of the mint in the port of Vienna was withdrawn from him, which made it much more difficult to manipulate the goods. He solved the problems with the Brennberg by sub-leasing the pits to Alois Miesbach, who endeavored to cover the fuel requirements for his brick kilns at low cost.

The canal under the "brick barons" Miesbach and Drasche (1846–1871)

When no offer was received at the verbal auction of the canal lease on November 9, 1846 at the calling price of 10,975 guilders, Alois Miesbach was awarded the contract with his written offer of 15,551 guilders. Miesbach was also one of the greats of the Austrian economy. In 1826, with the rule of Inzersdorf, he had acquired rich clay deposits, which served as the basis for a building materials company that last comprised 30 mines, a terracotta factory and nine brick factories, thus laying the foundation for the building materials group Wienerberger , which is now active worldwide . Under Miesbach, the problems escalated with the town of Ödenburg, where speculative companies had settled, which asserted the contractual claim to cheap coal for Ödenburg citizens and were given justice in the Hungarian courts. When Miesbach refused to deliver coal to such companies, execution was obtained, which, however, was prevented by the court chamber. There was also trouble at the other end of the canal shops, in Vienna. There, the company under the direction of Carl Ritter von Ghega , who later built the Semmering Railway , was awarded the last two kilometers of the canal as a railway line for the construction of a connecting railway between the individual Viennese railway stations. On May 24, 1848, construction work began on the new canal port and the feed channel for the factory owners under the new port who were in a contractual relationship with the canal company. On April 24, 1849, the sections below the disused Rennweg sluice were lowered and the canal bed was redesigned into a railway body. From June 11th, the factory owners received their canal water again.

Miesbach, who was damaged several times by the shortening, did not file a lawsuit, as he was awarded a lease reduction to 6000 guilders and the lease was extended. With the construction of a branch canal to the Biedermannsdorfer brick kiln, he was able to improve his competitive position, but he had to accept that in 1855 he lost an important canal customer, Count Hoyos. When Miesbach died in 1857, his nephew Heinrich Drasche, later Heinrich von Drasche-Wartinberg , took over the business.

The sale of the canal and the official cessation of shipping operations (1871–1879)

The lost Prussian-Austrian war of 1866 had brought the state into financial difficulties, which they tried to resolve not least by selling state property. The channel was also made available for disposal. When calculating the sales amount, the value of the objects built, the value of the shipping lease, the income from ice extraction, the provision of plant and industrial water, as well as servitude rights, the sale of "overstuffed" trees, the income opportunities from unused slopes and the Contractually guaranteed feed water (Leitharigole, Kehrbach, Guntramsdorfer factory water) is used. Property tax, long-term leases, maintenance and personnel costs were accounted for, resulting in a net present value of 279,855 guilders. On February 16, 1869, a preliminary contract was signed with the “kk privileged Österreichischen Vereinsbank”, which led to the establishment of the “Erste Österreichische Schiffahrts Kanal AG”, which paid a purchase price of 350,000 guilders. Since this sale was not in accordance with the lease, the surprised Drasche brought a lawsuit against the court chamber, which led to a settlement and Drasche's exit from the contract. The legally valid change of ownership took place on May 15, 1871.

Although the new owners made net profits on the canal in the following years (1872: 15,560 guilders, 1873 over 30,000 guilders), their focus on railway construction remained fixed. On October 19, 1872 the authority was given to build and operate railway lines. The company was thinking primarily of building a railway from Vienna to Neusatz an der Donau (now Serbian: Novi Sad), where it was hoped to connect to the Saloniki - Mitrovica line, which has existed since 1873, and thus to establish a connection between Saloniki and Vienna . In 1874 the permit for preparatory work for the Vienna– Aspang - Friedberg - Radkersburg route , the Aspang Railway , was granted. In 1876 the company applied for a concession to build as far as Aspang and received it. With regard to financing, an agreement was reached with the “ Société belge de chemin de fer ”, the Belgian state railway company, which has now taken over the helm. First, the “Erste Österreichische Schiffahrts Kanal AG” was renamed the “Austro-Belgische Eisenbahngesellschaft” (“Austro-Belgische” for short). Then the Belgians founded the Aktiengesellschaft Eisenbahn Wien-Aspang (EWA), to which not only all the concessions and rights of the Austro- Belgians relating to railway construction were transferred, but also the port area and the seven-kilometer-long canal stretch to Kledering including the Liesing aqueduct. The "Austro-Belgische", which had just been renamed "Eisenbahngesellschaft", thus became a pure canal company again, which continued to be responsible for the water supply to the contractual partners. The canal therefore remained water-bearing in this part until 1930, but had to share the bed with the single-track Aspang Railway. When, after this extensive adaptations the flume below Kledering filled again in May 1881 there were similar problems in 1803, leaking or ruptured water channels forced several times to drain the long attitude to Krottenbachschleuse.

The canal after official shipping operations ceased (1879–2000)

The long farewell to shipping (1879–1914)

Although shipping was no longer officially started after the renovation work, it did not come to a rapid end even after the second shortening of the canal and the completion of the Aspang Railway, which began operating as far as Pitten in 1881. A letter from the director of the "Austro-Belgische", Tunkler von Treuimfeld, from the year 1887 (!) Shows that

- "Shipping operations for the purpose of transporting third-party loads ... are ordered by the headquarters on a case-by-case basis."

Since in the course of this "occasional" operation, goods were still taken over at eight charging stations and transported by company staff, this does not seem to have been rare. The only restriction: In the case of non-regular transports, the company only provided the boat, the towing gear and, for new customers, a pilot.

Despite the limited operation, the canal was able to keep a positive balance until 1890, when the rail competition made itself more and more noticeable through falling freight rates. The decay of the canal due to lack of money continued and restricted shipping traffic even further. The reduced supervision and maintenance was also felt by the users of sewer water, who complained about reduced water quantities due to leaks and unauthorized withdrawals and also complained about the increasing weed growth.

The First World War and the Kehrbach Umlauf (1914–1918)

Since the main water supply for the canal still had to be via the “Leitha-Rigole” and the Pöttschinger branch, draining this stretch was initially out of the question. In 1903, the already desolate wooden structure of the Leitha aqueduct was replaced by a steel structure with concrete foundations. When a flood destroyed the unfinished foundations in 1905, only the wooden structure was repaired and the shortened iron structure was used for the reconstruction of the Schwechat aqueduct near Baden . After the "Kehrbachumlacement", the Pöttschinger branch was drained on April 18, 1916. The dams and bridges in the corridor areas were not removed until 1964, with 20 hectares of arable land being gained. When the port was filled in and the approach to the port in Wiener Neustadt in 1926/1927, the canal was shortened by a further 600 m and has since ended or started on the northeastern edge of Wiener Neustadt at the Ungarfeld power plant.

The decline of the canal (1918–1956)

Because of the involvement of members of an "enemy state", the "Austro-Belgische" was placed under state supervision during the First World War . The maintenance of the canal suffered due to the recruitment of operating staff and the confiscation of horses, which led to water shortages and corresponding lawsuits from the plant owners. As these deficiencies were taken seriously by the authorities because of the armaments contracts of these companies, the Kehrbach Umschlag was forced, which brought an improvement from 1916 onwards with more water in the canal.

Inflation and the decline of many businesses on the canal after the collapse of the monarchy aggravated the financial situation of the company, which from April 15th called itself "Austro-Belgische Eisenbahn- und Industrie AG". The lack of funds for maintenance led to supply shortages, to which the factory owners reacted by discontinuing the lease payments. In addition rubbers:

- “Finally the channel got into complete neglect. The canal was swampy, silted up and covered with reeds several meters high. In 1926 it was so bad that the factories could hardly be kept running. "

When the "Austro-Belgische" decided to open the canal, they found a lot of support from the neighboring communities, who expressed interest in the property. However, since the users of the canal insisted on their contracts, the state of Lower Austria intervened and had the canal from Vienna to the Krottenbach drained and the remaining channel rehabilitated with the support of the state and the plant owners. This work was completed in 1930. The negotiations with the municipality of Vienna and the local beneficiaries dragged on until 1933, with the city receiving the remaining municipal land of the company for assuming all liabilities of the canal company.

From 1931 the "Austro-Belgische" presented itself under new management. Leo Grünberg made an effort to put the operation of the now renovated sewer on a better financial basis. As part of the government's job creation program, he managed to raise funds for the construction of 13 small hydropower plants. These systems were built in 1935 and 1936 between Baden and Kottingbrunn at locks numbers 18 to 33, locks 26, 30 and 31 being canceled because their slopes had already been used for another purpose.

The canal suffered severe damage during World War II . Because the "Alpen- und Donaureichsgaue" (Austria) were initially spared from air raids, numerous industrial companies from the "Altreich" were relocated here from 1942, with the canal proximity being sought mainly because of the extinguishing water supply. The largest industrial company on the waterway, Flugmotorenwerke Ostmark , whose 200 hectare area is identical to today's industrial center Lower Austria South , had already acquired the section between the Krottenbach and the canal 300 m south of the Haidbachablass in 1942. When bombs began to fall in Austria on August 13, 1943, they initially targeted the aviation industry. This had its most important operations with Wiener Neustadt ( Messerschmitt ), Bad Vöslau (Messerschmitt) and Wiener Neudorf (Flugmotorenwerke Ostmark) in the immediate vicinity of the canal. During these attacks, the canal was hit directly by 127 bombs and was largely dry from the end of April 1944. The ground fighting in the first days of April 1945 between parts of the German 6th SS Panzer Army and the Soviet 3rd Ukrainian Front caused further destruction . Several bridges were blown up, lock systems and small power plants were destroyed and industrial companies with canal connections were devastated. The aqueduct over the Liesingbach was provisionally repaired with steel girders to guide the Aspang Railway . After the relocation of the Aspang Railway with its integration into the Eastern Railway, the remains of the structure were removed around 1980.

Since the necessary general renovation was in no relation to the available funds and possible income, the "Austro-Belgische" decided again to shut down and fill the canal.

New owners and new functions

Shortly before the drainage was implemented, the Lower Austrian Chamber of Commerce intervened and acquired the canal shares and all liabilities in the interests of several chamber members, but could not bear the burdens associated with maintenance in the long term, as the desired waterworks cooperative, which was supposed to take over the canal operation, did not materialize . In 1956, the province of Lower Austria took over the southern part of the canal, and the purchase agreement was signed on July 12, 1956.

The section that was owned by the aircraft engine works was largely dry even after the partial renovation of the southern section of the canal, as the canal water in the area of the Guntramsdorf – Laxenburg municipal boundary was diverted at the so-called “Haidbachablass” into the nearby Haidbach ( Badener Mühlbach ). After the ownership rights to the property of the Flugmotorenwerke had been transferred to " Industriezentrum Niederösterreich Süd GmbH" (IZ NÖ-Süd), the obligation to maintain the canal anchored in the original purchase agreement was issued. In view of the massive destruction, especially in the northern part, a compromise was reached after lengthy negotiations. The part of the canal up to the Mödlingbach was renovated in the early 1970s, but the section up to the Krottenbach was finally closed. In 2007, the canal part of the "IZ-Süd" became the property of the " ECO-Plus operating management companies ".

The historical functions of the canal

Freight transport

- The coal

Despite the intentions of the Wiener Neustädter Hard Coal Union , coal by no means became the dominant cargo. The product from the Ödenburger Brennberg remained too expensive due to the unfavorable contracts and the lack of a sewer connection, and the leased deposits in the Wiener Neustadt area soon turned out to be unproductive. The contribution made by the canal operator to the triumphant advance of this energy source in Austria was therefore small. Its steep rise did not begin until the railway boom in the second half of the 19th century, with the railway taking part in it several times. Through its own needs, it stimulated coal production itself, it made steam engines generally popular and also created the common energy source itself. Tall, smoking factory chimneys became a trademark for progress and success. When in 1870 the coal consumption of the Viennese rose from 50,000 tons to 200,000 tons, this coal came mainly from Bohemia , Moravia and Silesia and not from the south.

- The wood

Instead of coal, wood , and mostly firewood, was at the top of the transport list. This product mostly came from the forests of the region around Rax and Schneeberg , which were mainly owned by the Counts of Hoyos . In Georg Hubmer , a brilliant washer was found who contracted in 1805 to bring 10,000 fathoms (approx. 35,000 cubic meters ) of firewood to Wiener Neustadt and Vienna annually from 1807 . Hubmer not only organized the moving (bringing) of wood , with the help of the Count he also received the flood privilege on the Schwarza, the permit to adapt the Kehrbach as an alluvial canal and the permit to use the canal with his own ships at a flat rate of 20 guilders per boat (outward and return).

Since the annual average of the amount of wood delivered on the canal to Vienna between 1808 and 1827 was 28,000 fathoms, it is clear that Hubmer alone contributed half of this amount. In total, between 1840 and 1852 it delivered 240,519 fathoms to the capital and residence city, which corresponded to an annual output of over 20,000 fathoms (or 70,000 cubic meters). When the canal became continuously navigable for the wider ships at the beginning of the 1850s, the court chamber of Hoyos wanted more money for the transport. But Hoyos, who suffered from the drop in the price of logs due to the conversion of the Viennese factories to coal, canceled the contract on February 14, 1856, which meant a considerable reduction in income for tenant Alois Miesbach.

Not inconsiderable amounts of wood also came from the Schwechat catchment area . This wood was initially carried by means of the hermitage in Klausenleopoldsdorf to the western edge of Baden and via the hermitage near Urtelstein on to the wood rake in Möllersdorf an der Reichsstraße, from where it was transported to Vienna by cart. However, since a lot of wood was lost between Baden and Möllersdorf, a new wooden rake was set up just after the Urtelstein in 1804 and the logs were transported from there on July 7, 1804 to Baden- Leesdorf , where they were at the loading station at lock 15 of the canal were loaded onto barges for transport to Vienna.

- Other goods to be transported

When the timber transport declined with the termination of the contract by Count Hoyos, bricks became the most important cargo. At the beginning of the 1870s, for example, there was only one ship a day from Wiener Neustadt to Vienna, while 10 barges from the brickworks were dispatched from Guntramsdorf. Roof tiles, lime, pig iron as well as resins and pottery were also shipped to Vienna. In the opposite direction, iron goods, clay, graphite, barite, salt, sugar, wine and Mauthausen granite were transported with which the streets of Wiener Neustadt were paved.

- Passenger transport

In addition to goods, people were also transported. Three times a week a “pleasure ship” ran from Vienna to Laxenburg , which aroused interest as the imperial residence ( Laxenburg Palace ) and the large public park. At the time of the autumn maneuvers, daily trips were made and up to 80 people were transported per boat. You paid 36 cruisers for the return trip. Due to the long journey time, interest in this entertainment died out in the 1830s.

- freight charges

The freight prices were graded according to weight, cargo and distance. In 1868, for example, you had to pay a total of 24 guilders for the transport of a shipload of firewood from the Siebenhaus loading station (lock No. 34) to Vienna. For a hundredweight (approx. 56 kg) of delicate freight, 7 cruisers had to be killed on the same route, which meant 38 guilders for a shipload (30 tons).

The canal as a source of energy and water

The interest in the canal as a source of energy and water was great from the start, after all, using the "gradient" (lock steps), one could operate mills, saws and drills relatively inexpensively without having to rely on expensive fuel. The only disadvantage was the fact that the applicant was not guaranteed a constant water supply; in the event of damage and renovation work on the channel, one had to reckon with having to do without this energy source for weeks and months, and without any claim to replacement. Water was also popular for filling fish ponds, watering gardens, and meeting paper mills' water needs. Since the applicants had to bear considerable initial investment, the contracts were concluded on a long-term basis, which should prove to be a heavy mortgage if parts of the canal were abandoned. A total of 19 canal-related businesses settled here.

At the end of the 1850s, the supply of drinking water to the rapidly growing metropolis of Vienna became an ever greater problem. After the canal was ruled out as a source of drinking water, the municipality of Vienna announced a competition to solve the problem at the end of 1861. On July 7, 1864, the project was implemented that wanted to convey high-quality water from the Rax and Schneeberg area to Vienna. Since this water was withdrawn from the Schwarza, the canal fund protested against the discharge of these springs, as well as other victims. To compensate for the loss of water, it was demanded that the water from the Pitten be discharged into the Kehrbach, which was rejected (at that time) due to the high costs. In view of the primary interests of the capital and residence city, the canal owners had to accept a one-off compensation of 100,000 guilders.

The first Viennese hydropower plant was located in the outflow channel on Linke Bahnzeile in Vienna (research status 2016): A turbine was installed in rooms next to the route of the connecting railway or today's main S-Bahn line , which drove a generator via a transmission belt . The lighting of the Beatrix baths, built in 1888/1889, was supplied with electrical energy from this power plant.

Ice extraction on the canal and other uses

The function of the canal as a supplier of ice should not be underestimated either. In winter, due to its shallow depth, the canal was an ideal place to cut blocks of ice, which were of great importance to innkeepers and breweries as a source of cold in summer. In the cities canal water was also valued for sprinkling streets, watering gardens and flushing rubbish canals.

The canal's infrastructure

Length of the channel

The length of the canal (carrying water) was 56 kilometers in 1803 (Port of Vienna to Port of Wiener Neustadt). It was expanded to 63 kilometers in 1811 with the expansion to the Pöttschinger Sattel and in 2007 it is 36 kilometers long.

Water supply

The seasonally strong fluctuations in the amount of water in the surface water in the Vienna Basin made sufficient filling of the canal one of the main problems of the project, especially since the loss of 2/5 of the amount of water due to evaporation and "seizure" had to be expected. Maillard therefore planned an "economic" canal, which he mainly understood to be narrow lock chambers, which were supposed to keep the loss of water low during the lock. Despite these precautions, a complex feed system became indispensable, including ponds that temporarily stored the water required for the locks at the triple lock in Guntramsdorf.

- Infeed 1801-1916

From the sample fillings in 1802 onwards, the Leitha was the main source of water. But water from the Kehrbach, the Hirm and factory water from Guntramsdorf and Gumpoldskirchen had also been secured. With the Schwarza coming from the Rax-Schneeberg area and the Pitten from the Wechsel area , the Leitha has two source rivers that flow together at Haderswörth , the "Leitha origin" (see sketch 10). The Leitha water for the canal was diverted from the Neudörfler Leithamühlbach near Neudörfl after the mill and led over the 3 km long “Neudörfler Rigole” to the east into the Heutal (see sketch 10). Here it met the temporary end of the Pöttschinger branch of the shipping canal, which was only built in 1810 to the then Hungarian border. The water flowed in the canal over the mighty Leitha aqueduct back towards Wiener Neustadt, where it also filled the Vienna branch of the canal from the "triangle". In order to ensure a permanent water supply in the central and northern part of the canal, water was also introduced from the Hirm and 16 smaller inlets between Baden and Guntramsdorf when shipping was in operation. As far as the Kehrbach water is concerned, the Neunkirchen district administration stipulated on May 15, 1876 that it could only be used to feed the sewer in the event of insufficient water flow from the Leitha.

- Feed-in from 1916

Since the "Neudörfler Rigole" partly ran over royal Hungarian territory, which repeatedly caused problems, the "Leitha-Fischa-Wasserwerkverein", an association of 37 factory owners at Kehrbach, Fischa and Leitha, agreed on the "Neudörfler Project". No longer the Leitha, but the Kehrbach should supply the majority of the club's members with water. To ensure that there was sufficient water even in dry times, the "Katzelsdorfer Mühlbach" should no longer be returned to the Leitha at the end of the village, but instead should be routed via the "Katzelsdorf supply channel" through the park of the Theresian Military Academy into the Kehrbach. In addition to a better water supply, this project also offered the canal company the opportunity to drain the Pöttschinger canal branch. The project was submitted in 1907 and accelerated after the outbreak of war, as the fulfillment of war-important orders was endangered by a lack of water. The new feed came into force in 1916, initially without "approval".

Today the Kehrbach carries up to 7,000 liters of water per second on its 16 km long course from Peisching to the northeast edge of Wiener Neustadt, which is taken from the Schwarza. The gradient of over 90 meters is used to operate the Föhrenwald, Brunnenfeld, Akademie and Ungarfeld power plants. In front of the Ungarfeld power plant, an annual average of another 3,000 liters / sec, coming mainly from the Pitten, are introduced into the Kehrbach via the “Katzelsdorfer supply channel” . At the Ungarfeld power plant, the Kehrbach conducts at least 1000 to a maximum of 1440 liters per second into the Wiener Neustädter Canal.

- Feeding details

The locks

The canal locks consisted of the lock chamber and the upper and lower lock heads that supported the single-winged upper and double-winged lower lock gates . The gates were moved with the integrated rotating beams .

In the locks, the ships were raised or lowered by 6 feet (1.9 m). Lock No. 34 was an exception at 7 feet 2 inches (2.34 m). The locks divide the channel into conversations , with name / number of attitude corresponds to the upper water. The locks were also used in the regulation of the water level of the upstream water, wherein the prescribed voltage (filling) of the respective attitude was reviewed by the lock guards by means of levels and regulated by the insertion of weir boards in the circulation channels. After the dams were sufficiently consolidated, the tension was increased by one foot (32 cm) to 5 feet (1.58 m). In addition, from 1820 onwards, as part of the annual repairs, the locks were not only gradually renewed, but also widened by a foot (32 cm). When this measure was completed in 1850, the entire canal could be used with wider barges, which could load 30.8 tons instead of 22.4 tons.

The number of locks was initially 50, with which 103 meters of altitude were overcome. In the part that is still water-bearing today (86 meters above sea level) there are still 40 lock structures in varying degrees of conservation. Of the locks in the abandoned area, only the one on Krottenbach has been preserved. Basically, it was a single lock. To overcome greater differences in height, three double locks were built in Vienna and a triple lock near Guntramsdorf. With these multiple locks, the lock chambers were located directly behind one another, which saved 1 or 2 gates. The locks were given names from Vienna to Guntramsdorf (sketches 3, 4, 5), and from Gumpoldskirchen were numbered from 1 to 36 (sketches 6, 7). The chamber of a single lock had a two-winged lower gate, which was designed as a mitred gate . With this design, the wedge-shaped upward-pointing gate leaves (Fig. 1) are pressed against each other by the water pressure. The single-leaf upper gate was two meters shorter. The chambers of the named locks were built from the beginning in stone block construction, the rest in a mixed construction method, whereby the long chamber walls between the heads were built in cost-saving brick construction. Since the mortar used in the brick sluices proved to be insufficiently waterproof, repairs were required in relatively short periods of time. At the beginning of the lease, the Hofkammer began to oblige the leaseholders to build at least one object per year in a square construction as part of the lock widening project. This project was only carried through to lock 25.

During the passage (using the example of a barge moving uphill ) the ship was first pulled into the lock chamber and the lower lock gate was closed with the rotating booms . Then skippers or lock keepers opened the two "gates" (sliders) on the gate passages (inflow channels) on the upper main lock. This was done with the help of a crank and the rack gear attached to the winch columns (Fig. 4). The water then flowed through the semicircular openings, which are located on the left and right in the S. walls of the upper lock head (Fig. 3), via the mentioned gates into the lock chamber, which was filled within three minutes. Lock chambers were not emptied, as shown in Maillard (sketch 12), by elaborate gate passages in the side walls, but generally by gates in the lower gate wings. (Fig. 1)

- Lock details

Water crossings, bridges

- Water crossings

Smaller channels are carried out with culverts or culverts (there were 26 in 1803) under the canal. The canal crosses larger watercourses with the help of aqueducts . Of these 16 structures of the final expansion stage in 1911, seven are still in operation. These are the aqueducts over the Kehrbach , the Warme Fischa , the Piesting , the Triesting , the Triestinger Hochwassergraben (also called Schleiferbach), the Schwechat and the Badener Mühlbach. The water flowed in wooden troughs, which were mostly replaced by concrete troughs. The Liesing and the Fischa were / are crossed in bridges made of brickwork.

- bridges

At the time of commissioning, 54 bridges crossed the canal, nine of which have been preserved in their original state, at least visually. They were mostly built as brick vaulted bridges, but there are also pure stone bridges. From lock 22 uphill, the span of the crossings was increased by almost one meter (see sketch 14) and provided with two stairway paths. With the rise of the water level by one foot in the years after 1820 and the widening of the locks by one foot, the stairways had to be raised accordingly and the passageways widened, which led to the omission of the second stairway on the southern bridges. Since the supporting structures were only designed for loading with horse-drawn vehicles, they were replaced by more stable structures made of other building materials in the course of the motorization. Thus the old bridge structures were only preserved in the field path area. When these structures were transferred to the responsibility of the respective municipalities in the 1980s, they were partly removed for safety reasons or, while preserving the monumental character, they were costly adapted to current traffic requirements by inserting a reinforced concrete slab. The names of the bridges are inconsistent.

Loading and unloading points

The port at the end of Vienna was initially near the confluence of the Wien River with today's Danube Canal (today Wien Mitte station ), but in 1849 it was moved just under two kilometers south to the point where the Aspang station was later built. In Wiener Neustadt the harbor was on Ungargasse opposite the Neuklosterkirche. In winter, the barges were housed in the shipyard (see sketch 8), which also served as a winter harbor. There were up to ten additional loading stations along the canal, some of which provided accommodation for the ship's crews and operating personnel as well as stables and feeding places for the draft horses. The most important of these loading points were Leopoldsdorf (branch canal to brickworks), Biedermannsdorf (branch canal to brickworks), Guntramsdorf (branch canal to brickworks), Leesdorf (lock 15 with branch canal), Siebenhaus (lock 34) and Sollenau (lock 36). The importance of Pöttsching remained minor.

The canal in the 21st century

The current functions of the channel

- Ecological function

The canal shapes the landscape with its rows of poplar trees ( designated as a natural monument near Baden ) and engineering structures. Since the canal embankments are usually only mowed on one side, the canal area represents a refuge for not a few, in some cases rare and threatened, plant and animal species. The canal area is also in the biotope network with the adjoining habitats, among which there are some interesting wet areas and especially in the Kottingbrunn area with large-medium there are extensive dry areas. Poplars are predominant on trees, willow is rarer. Shrubs are mainly represented by dogwood species ( Cornus sanguinea and Cornus mas ), blackthorn , scapular cap , hawthorn and dog rose . They are often entwined with clematis (mostly Clematia vitalba ). In the smaller plants are in water near the marsh marigold , the attractive water iris and reeds , the great water dock , the Common butterbur , tape grass, the water-sweet grass with his big panicles of rape and reed canary grass to name. Also marsh sedge , purple loosestrife , meadowsweet and comfrey are not uncommon. In the higher embankment, dam and bank path areas, plant species of the dry meadows predominate. To name are u. a. Meadow goat whiskers , wound clover and other types of clover , sage , thyme , sun rose , field stone seeds and the upright trespe . With the nettle , the dandelion and the mugwort , members of the ruderal society are also represented.

In addition to fish, the main animal species are waterfowl such as the mallard duck and the coot, which are always present .

- Water management functions

Water is taken from the canal for irrigation, for fishpond feeds (Schönau an der Triesting, Guntramsdorf) and for industrial purposes. The function as a source of extinguishing water should not be underestimated. When snowmelt and heavy thunderstorms , the canal between Baden and Guntramsdorf takes on some streams such as the Thallernbach in Gumpoldskirchen , it also serves as a receiving water for various sewage treatment plants.

Of the 13 small power plants built in 1935 and 1936, almost half were destroyed or devastated during the war or during the occupation. Today, the state of Lower Austria operates locks 18, 20, 21, 22, 24, 27 and 32, which feed an average of 600,000 kilowatt hours per year into the Wiener Stadtwerke network ( Wien-Strom ). In the attitude of 13 produced Casinos Austria electricity for their own use of their central warehouse, in the attitude 9 in space Pfaffstätten is in March 2006 as a pilot project of the Viennese inventor Adolf Brinnich a dynamic pressure machine in operation, of which one a higher efficiency in small power stations is expected.

- Use for fishing purposes

The fishing rights holders (Province of Lower Austria, ECO-Plus) have leased the fishing rights to the sport fishing associations of Baden and Guntramsdorf. The association from Baden uses the districts Wiener Neustädter Kanal DI / 1 and DI / 2, the districts DI / 3 and DI / 4 (ECO-Plus) that from Guntramsdorf. Zander , trout , pike , carp and white fish are released and caught . Out of consideration for fishing, the canal is not completely drained during the annual “turnaround”, but fishing in the then very restricted habitat is prohibited.

An ice jam at the weir system Peisching caused fish deaths in the winter of 2012 because the canal with no inflow from Wiener Neustadt to Sollenau was without water for three weeks. More than 20 species of fish have died.

- Use as a recreation area

Because of the mild winter and the current, ice skating is no longer in the foreground. Rowing is interesting, but because of the many locks, it is only interesting in the lock-free area between Wiener Neustadt and Sollenau. A boat rental is located at the "Triangel". Today, the waterway is most popular with hikers and cyclists. The latter find ideal conditions on the now paved stairway. Both the Thermenradweg and the EuroVelo 9 use this.

Condition and maintenance of the sewer

After shipping on the canal had been suspended since the First World War, the lock gates that were no longer needed were removed and, instead of the upper gates, some gates or fixed thresholds were installed to keep the water level in the reaches to a certain (in practice very different) To maintain level. The inflow and outflow openings for filling the chamber were bricked up many times, as damaged inflow channels endanger the lock walls themselves. Repair work on the locks only has a conservation character, while attention is paid to full functionality of the aqueducts.

The canal and its catchment area are maintained by two employees from the hydraulic engineering department of the Province of Lower Austria. The Kehrbach, Katzelsdorfer Mühlbach and the canal to Schönau an der Triesting are managed from Wiener Neustadt, the rest of the area including the canal parts owned by Ecoplus are managed from Kottingbrunn . Maintenance means ongoing checks of the condition, the elimination of minor defects and defects, mowing the canal embankments and inspecting the small power plants. These maintenance bodies receive reinforcement for major construction work and for the annual "sweeping" of the canal (removal of mud and gravel as well as debris). The costs for these activities are borne by the state of Lower Austria, they are reduced by contributions from the federal government, the municipalities and the economy, furthermore by income from permits (servitude and land rent, fishing lease, etc.) as well as the income from the electricity generation of the seven small power plants.

Traces in the abandoned area

In the abandoned areas, the existence of the Wiener Neustädter Canal can at least partially be traced. In Vienna, traffic areas such as "Hafengasse" and "Am Kanal" are reminiscent of shipping times. The last-mentioned street runs between Rennweg and Kledering for several kilometers along the railway line that used parts of the canal bed from today's Wien-Mitte train station. Archaeological excavations in 2009 on the site at Hafengasse in the 3rd district of Vienna (area of the former Aspangbahnhof ), which were carried out as rescue excavations before the construction of new residential complexes, found remains of the former harbor basin. The mouth of the canal into the harbor basin and the eastern and southern harbor walls were still well preserved. In addition, a pit with Roman ceramic remains was found in this area, which was considered to be a material extraction point for brick production. In addition to the remains of the canal harbor and the course of the canal, further excavations documented a Roman grave building in this area.

Beyond the old line wall, the construction of the central marshalling yard of the Austrian Federal Railways (ÖBB) has obliterated numerous traces. In the fields to the south, too, only the aerial photo provides information about the course of the canal. To the east of the S 1 , a section of canal with a length of 500 meters is still well preserved in 2007. It doesn't quite lead to the former aqueduct via the B 16, the old Ödenburger Straße . Immediately to the west of this street, on the crown of a 6 m high embankment, you will find the canal bed, kept free from undergrowth, which can be traced 300 meters to the former aqueduct over the Petersbach . Grain was also grown here on the basis of the fertile canal mud. After the Hennersdorf – Leopoldsdorf road, the initially clear traces of the waterway disappear after 200 m in the fields. In the wind protection belt, which runs 1,000 m further south before Achau towards the west, you come across a well-preserved, albeit overgrown section of canal that you can follow over a kilometer to the track of the Pottendorfer line of the ÖBB. 450 meters west of the railway, the row of trees continues to the west, it hides the water-bearing part of a towing canal that canal leaseholder Miesbach had built in the 1850s as a connection to one of his brickworks. At the east end of this approx. 1,200 m long channel, the retaining walls of the entry structure have been preserved. Today only four ponds and sparse remains of the foundations remind of the brickworks at the west end.

The main canal led from the east end of the brickworks to the south, where after 200 meters in the wood on the banks of the Krottenbach you can find the remains of the Krottenbach aqueduct, a lock and foundations of the paper and cardboard lid factory built by Karl Rheinboldt in 1812. In 1930 the canal at the southern end of this viaduct was bricked up and the water was directed into the Krottenbach. During the Second World War, the lock chamber was adapted as an air raid shelter with a solid concrete ceiling. If you follow the overgrown canal remnants further south, after a good kilometer you come to the Mödlingbach and the current end of the waterway.

In Wiener Neustadt a plaque in the Ungargasse indicates the existence of the former canal port. The Gasse Am Kanal accompanied the watercourse from the harbor to the Kehrbach. Its extension, the right channel line , leads next to the current channel to its sharp left bend, the "triangle". The Pöttschinger canal branch continued exactly as an extension of the right canal line . If you follow this line, defined by a driveway, you will first come across allotments that were built in the canal bed, the dam structure is still clearly visible here. Such traces are missing in the subsequent fields. After a good kilometer, only a stone between two trees reminds of the Kriegsfleck bridge (see picture). This name recalls the death of the last Babenberger who fell here in 1246 in the battle against the Hungarian king Béla IV . Following the imaginary straight 800 m further to the Hauslüsse forest , you come across a well-preserved section of canal which, after a bend, leads to the (mostly dry) Leithabett, over which the canal was led in a 65-meter-long wooden trough. Only the canal house on the right bank of the Leitha is reminiscent of this building. Traces of the rest of the waterway can only be seen in the aerial photo.

Geospatial data

- Canal port of Vienna (1803 to 1849): 48 ° 12 ′ 23 ″ N , 16 ° 23 ′ 5 ″ E

- Canal port of Vienna (1849 to 1879): 48 ° 11 ′ 25 ″ N , 16 ° 23 ′ 41 ″ E

- Northern end of the canal (current): 48 ° 4 ′ 45 ″ N , 16 ° 21 ′ 31 ″ E

- South end of the canal (currently): 47 ° 48 ′ 53 ″ N , 16 ° 15 ′ 25 ″ E

literature

The most important basis of the present article was Valerie Else Riebe's work Der Wiener Neustädter Schiffahrtskanal (Gutenberg Verlag, Wiener Neustadt 1936). Riebe relied primarily on the files of the court chamber archive and the Austro-Belgian Canal Society. Beside her there is also Fritz Lange, a well-founded expert on the history of the canal for our time, who wrote the monograph From Vienna to the Adriatic - The Wiener Neustädter Canal (Sutton-Verlag, Erfurt 2003, ISBN 3-89702-621-X ) In addition to Riebe's work, it also brings in the development from 1936 to 2003.

- Josef August Schultes : Excursions to the Schneeberge in Lower Austria. A paperback on trips to the same. The Vormärz in the district under the Vienna Woods. A sociopolitical illustration . New edition of the Vienna 1802 edition. Rotary Club Wiener Neustadt, Wiener Neustadt 1982, OBV .

- Sebastian von Maillard: Instructions for the design and execution of navigable canals . Hartleben, Pesth 1817, ÖNB .

- Administration of the kknö. Schiffahrts-Kanal (Ed.): Regulations for the acceptance of freight at the kknö. Shipping Canal . Vienna 1866.

- Friedrich Umlauft: The Wiener Neustädter Canal . In: Communications from the KK Geographical Society in Vienna . Volume 37.1894. KK Geographische Gesellschaft in Wien, Vienna 1894, OBV ( Memento from July 26, 2013 in the web archive archive.today ).

- Valerie Else Riebe: The Wiener Neustädter Schiffahrtskanal. History of a Lower Austrian building from its creation to the present according to archival sources . Gutenberg publishing house, Wiener Neustadt 1936, OBV .

- Josef Knoll: Heimatbuch Guntramsdorf . Guntramsdorf 1977.

- Paul Slezak, Josef Otto Friedrich: From ship canal to railroad. Wiener Neustädter Canal and Aspangbahn . International Archive for Locomotive History , Volume 30, ZDB -ID 256348-4 . Slezak, Vienna 1981, ISBN 3-900134-72-3 .

- Helmut Feigl (Hrsg.), Andreas Kusternig (Hrsg.): The beginnings of industrialization in Lower Austria. Lectures and discussions at the second symposium of the Lower Austrian Institute for Regional Studies, Reichenau an der Rax, October 1st to 3rd, 1981 . Studies and research from the Lower Austrian Institute for Regional Studies, Volume 4. Self-published by the Lower Austrian Institute for Regional Studies, Vienna 1982, ZDB -ID 581360-8 .

- Ernst Katzer: The “Wiener Neustädter Hard Coal Union” . In: Our new town. Papers of the Wiener Neustädter Monument Protection Association . Volume 26, episodes 2-4, and Volume 27, episode 1. Wiener Neustädter Monument Protection Association, Wiener Neustadt 1982/1983, OBV .

- Harald Ruppert: The Wiener Neustädter shipping canal . In: Simmeringer Museum Papers . Issue 12. Museumsverein Wien-Simmering, Vienna 1982, ZDB -ID 581530-7 .

- Rudolf Hock: Sollenau story (s). The Wiener Neustädter Schiffskanal. In: Nachrichten der Marktgemeinde Sollenau , S. a. , Issue 3–4. Sollenau 1986, OBV .

- Andreas Kusternig (Ed.): Mining in Lower Austria. Pitten, 1st – 3rd July 1985 . Lower Austrian Institute for Regional Studies, Vienna 1987, ISBN 3-85006-005-5 .

- Ludwig Varga, Robert Schwan, Davor Vytopil: The Wiener Neustädter Canal. History, description, inventory . Exercise, Institute for Monument Preservation of the Vienna University of Technology, Vienna 1989.

- Paul Slezak, Josef Otto Friedrich: Canal, nostalgia, Aspangbahn. Supplementary volume to the book "From the ship canal to the railroad" . Slezak, Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-85416-153-0 .

- Gertrud Gerhartl: Wiener Neustadt. History, art, culture, economy . Braumüller, Vienna 1993, ISBN 3-7003-1032-3 .

- Inge Podbrecky: The Wiener Neustädter Canal. In: Preservation of monuments in Lower Austria. Volume 10, traffic structures for roads, railways and canals. Vienna 1993.

- Karl Gutkas (Ed.), Josef Aschauer et al. : State history of Lower Austria. 3000 years in data, documents and images . 2nd updated edition. Brandstätter, Vienna / Munich 1994, ISBN 3-85447-254-4 .

- Silvia Hahn (ed.), Karl Flanner (ed.): "Die Wienerische Neustadt". Crafts, trade and the military in Steinfeldstadt . Böhlau, Vienna (inter alia) 1994, ISBN 3-205-98285-1 .

- Felix Rupp: Redesign options on Wiener Neustädter Canal in the Wiener Neustadt area. Development of the basics for improving the recreational value with special consideration of the ecological situation . Diploma thesis, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna 1996, OBV .

- Michael Rosecker (Red.): 200 years of the Wiener Neustädter Canal. 1797-1997 . Industrieviertel Museum, Wiener Neustadt 1997, OBV .

- Fritz Lange: From Vienna to the Adriatic Sea - The Wiener Neustädter Canal . Sutton Verlag, Erfurt 2003, ISBN 3-89702-621-X .

- Fritz Lange: The Wiener Neustädter Canal - forgotten and rediscovered in unique pictures . Sutton Verlag, Erfurt 2018, ISBN 978-3-95400-986-2

- Gerhard Trumler (photo), Fritz von Herzmanovsky-Orlando : boat trip to Tarockanien. The Wiener Neustädter Canal . Edition Portfolio, Vienna 2010, OBV .

- Johannes Hradecky, Werner Chmelar, Wiener Neustädter Canal. From the transport route to the industrial monument (Vienna Archaeological 11), Vienna 2014, ISBN 978-3-85161-069-7 .

- Friedrich Hauer, Christina Spitzbart-Glasl: Side advantages and inheritances of a waterway. Significance and permanence of secondary uses on the Wiener Neustädter Canal in Vienna. Viennese history sheets . Published by the Association for the History of the City of Vienna , 72nd year 2017, issue 2/2017. ISSN 0043-5317 . Pp. 155-187.

- Heinrich Tinhofer: 40 waterfalls towards Vienna - The Wiener Neustädter Canal , 2017, Kral-Verlag, ISBN 9783990247136

- Fritz Lange: Ships, locks, railways. Viennese history sheets. Published by the Association for the History of the City of Vienna, Volume 73, 2018, Issue 4/2018. ISSN 0043-5317 . Pp. 359-363. (on the course of the canal or the railway line between Rennweg and Canal Harbor in Vienna).

Individual evidence

- ^ Lower Austria - immovable and archaeological monuments under monument protection. ( Memento from June 26, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) . Federal Monuments Office , as of June 21, 2016 (PDF).

- ^ Rosecker: 200 years of the Wiener Neustädter Canal , p. 7 f.

- ↑ Slezak: Vom Schiffskanal zur Eisenbahn , p. 7. - Duty exemption: September 21, 1792, free coal: 1759.

- ↑ a b c Riebe, p. 26.

- ^ Hermann Mayrhofer: Channel for Readers . In: Rosecker: 200 Years of the Wiener Neustädter Canal , p. 35.

- ↑ Lange: From Vienna to the Adriatic .

- ↑ Riebe, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Riebe, p. 20.

- ↑ Riebe, p. 21.

- ↑ Riebe, p. 23.

- ↑ Riebe, p. 67.

- ^ Knoll: Heimatbuch Guntramsdorf , pp. 8–9.

- ↑ a b Riebe, p. 28.

- ↑ a b Riebe, p. 29.

- ↑ Riebe, p. 33.

- ↑ Slezak: From ship canal to railroad , p. 15.

- ↑ Riebe, p. 34.

- ↑ Riebe, p. 41.

- ↑ Riebe, p. 45.

- ↑ Hradecky - Cmelar, p. 72.

- ↑ Riebe, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ Riebe, p. 56.

- ↑ Riebe, p. 76.

- ↑ a b Riebe, p. 79.

- ↑ a b Slezak, p. 25.

- ↑ Lange: From Vienna to the Adriatic , p. 123 f.

- ^ Hermann Mayrhofer: Channel for Readers . In: Rosecker: 200 years of the Wiener Neustädter Canal , pp. 35–37.

- ↑ Riebe, p. 106.

- ↑ Slezak: From ship canal to railroad , p. 26.

- ^ Remains of the Liesing aqueduct , accessed on November 30, 2014.

- ↑ Slezak: From ship canal to railroad , p. 27.

- ^ Hans Rosmann: From the shipping canal to the canal. In: Rosecker: 200 years of the Wiener Neustädter Canal , pp. 26–34.

- ↑ Alois Brusatti (Ed.): The Habsburg Monarchy 1848–1918 . Volume 1: Economic Development . Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1973, ISBN 3-7001-0030-2 , p. 151.

- ↑ Riebe, p. 62.

- ↑ Slezak: From ship canal to railroad , p. 17.

- ↑ Riebe, p. 71.

- ↑ Hauer, Spitzbart-Glasl: Neben Vorteil, pp. 175–176. (with a schematic representation of the turbine system for power generation installed in the casemates in front of the Beatrixbad in 1889)

- ^ Hans Rosmann: From the shipping canal to the canal . In: 200 years of the Wiener Neustädter Canal. 1797-1997 . Industrieviertel-Museum, Wiener Neustadt 1997, OBV , pp. 13-14.

- ^ Jutta Edelbauer: Wiener Neustädter Canal. Fauna and flora . In: 200 years of the Wiener Neustädter Canal. 1797-1997 . Industrieviertel-Museum, Wiener Neustadt 1997, OBV , pp. 15-17.

- ↑ Ice jams cause fish to die . In: noe.orf.at , March 1, 2012, accessed on July 26, 2013.

- ↑ Schifferlfahrt on Wiener Neustädter Canal , accessed on March 13, 2015.

- ↑ Thermenradweg . In: fahr-radwege.com , August 8, 2010, accessed June 14, 2011.

- ^ Nikolaus Hofer: Find report. In: Find reports from Austria. Published by the Federal Monuments Office . Volume 48, year 2009. Berger, Vienna 2010, ISSN 0429-8926 , pp. 514-515.

- ^ Find reports from Austria. Published by the Federal Monuments Office. Volume 49, year 2010. Berger, Vienna 2012, ISSN 0429-8926 , pp. 478-482.

- ↑ see picture, sketch 5 and aerial photo: 48 ° 6 ′ 24 ″ N , 16 ° 23 ′ 52 ″ E

- ↑ see aerial photo: 48 ° 5 ′ 36 ″ N , 16 ° 22 ′ 35 ″ E

- ↑ see aerial photo: 48 ° 5 ′ 50 ″ N , 16 ° 20 ′ 47 ″ E

- ↑ see aerial photo: 48 ° 5 ′ 32 ″ N , 16 ° 21 ′ 34 ″ E

- ↑ see aerial photo: 48 ° 5 ′ 21 ″ N , 16 ° 21 ′ 33 ″ E

- ↑ Lange: From Vienna to the Adriatic , p. 47.

- ↑ see aerial photo: 47 ° 48 ′ 47 ″ N , 16 ° 14 ′ 52 ″ E

- ↑ see aerial photo: 47 ° 48 ′ 59 ″ N , 16 ° 16 ′ 2 ″ E

- ↑ see aerial photo: 47 ° 49 ′ 2 ″ N , 16 ° 18 ′ 12 ″ E

- ↑ Lange: From Vienna to the Adriatic , p. 126 f.

Remarks

- ↑ * 1746 in Luneville; † 1822 in Vienna; 1797 colonel; 1801 major general; 1812 Lieutenant Field Marshal.

- ↑ This pole was located just in front of the helmsman at the end of the ship; if it had been attached further forward, the helmsman would have had trouble compensating for the horse's pull towards the bank and getting the boat far enough into the lock.

- ↑ Rosmann was the chief sewer engineer in 2007.

- ↑ In this work, the designations from Slezak (1981) pp. 225–227 were used, although their sources are not named.

- ↑ Revier DI / 1 extends from the end of the canal in Wiener Neustadt to lock 35 on the Sollenau – Schönau state road, Revier DI / 2 to lock 13 near the state road Pfaffstätten-Traiskirchen, Revier DI / 3 to the Guntramsdorf-Laxenburg municipal border, the district DI / 4 to the Mödlingbach.

- ^ Message from DI Lange.

- ↑ a b c Without evidence, requested on July 26, 2013.

Web links

- The Wiener Neustädter Canal. District Museum Landstrasse, archived from the original on January 6, 2014 ; accessed on January 3, 2018 .

- Johann Werfring: Wood and coal for the old imperial city. In: Wiener Zeitung. March 17, 2011, supplement “ProgrammPunkte”, p. 7.

- Heinrich Tinhofer: WalkingInside - Canal Forum Independent initiative for the documentation and revitalization of the industrial monument Wiener Neustädter Canal.

- Fritz Lange: The Wiener Neustädter Canal

Coordinates: 48 ° 4 ′ 31 ″ N , 16 ° 20 ′ 59 ″ E