Economic history of Chile

The economic history of Chile is seen in its early phase as a continuous process of adaptation to the natural conditions of a country with extremely different climatic zones and therefore also extremely divergent flora and fauna , which resulted in a wide variety of cultures of hunters and gatherers , then fishermen and farmers in a small area . The economy of Chile has changed over the course of time from the heterogeneous economic methods of the various indigenous peoples to a colonial economy geared to the needs of Spain to an economy with a focus on raw material extraction and export, which was industrialized in the course of the 1930s . Chile's recent economic history is at the center of an intense debate in the course of which neoliberalism gained its modern significance.

The societies of Chile in the pre-Columbian period were based on fishing and farming cultures in the north and hunter cultures in the barren south. From the 16th century onwards, Spanish colonization forced economic integration into the Habsburg Empire. With the Spanish haciendas , the foundation stone was laid for the economically and politically dominant landed property in Chile and the mass of agricultural workers with almost no rights. The trade monopoly of the crown was eroded by smugglers as early as the 18th century , but formally ended only in 1810 with the independence of Chile. The Chilean economy went through different cycles. In the 17th century cattle breeding was the most important branch of the economy, in the 18th century wheat was grown. From 1873 to 1914 the rise and decline of Chiles nitrate production had a major impact on economic development. After that, copper mining became the dominant industry.

Due to the sharp collapse in world trade as a result of the global economic crisis and the subsequent Second World War , import-substituting industrialization took place in the 1930s and 1940s . After the normalization of world trade, this strategy was pursued with varying intensity in the 1950s and 1960s and aligned with the recommendations of the structuralists .

From 1973 to 1982, Chile was the first country to experience a radical turn in economic policy towards the economic liberalism of the New Right (commonly known as neoliberalism), primarily through the liberalization of foreign trade, privatization, deregulation and the dismantling of the (rudimentary) welfare state . A gradual change of course took place in 1983–1990 with the turn to “pragmatic neoliberalism”. Since the democratization of speech in 1990, there has also been a correction of course in social policy.

Pre-Columbian History (12,500 BC - AD 1541)

Hunters and collectors

Archaeological finds suggest that there was human settlement as early as the Pleistocene . The oldest finds in Monte Verde in southern central Chile could be dated to 12,500 BC. Found in Fell's Cave in Patagonia and Pali Aike in the extreme south to 11,000 BC. The first people lived as hunters and gatherers a . a. from hunting giant sloths , mastodons and guanacos , but also as fishermen.

Chinchorro: early fishing culture, first agriculture

One of the earliest cultures is the Chinchorro culture , which could be located in the extremely dry Atacama Desert . Although it did not develop a complex social organization comparable to that of the Egyptians or Incas , it was one of the first cultures to practice mummification . The oldest mummies could be dated 7000 BC. To be dated. Since the Chinchorro lived from fishing in the Pacific from the beginning, they mainly developed tools that were used for this kind of livelihood. Fishhooks were made from bones, shells or cactus spines. They used stone weights for deep sea fishing, stone knives, awls , harpoons and spear throwers. Despite the extreme drought, plant fibers were available to them because some of the rivers flowing from the highlands that touched the Atacama Desert formed alluvial cones . In these a reed-like grass grew, the fibers of which were used to make clothes, as an aid in the preparation of the dead and to make nets and fishing lines.

In the late Rivera III phase , i.e. between 2000 and 500 BC BC, the dependence on marine resources diminished. Instead, the importance grew cotton and wool, yucca and cassava were planted, but also the well-known as quinoa quinoa , which in the language of Quechua kinwa is. In the stomachs of some mummies there were remains of a small species of fish that had not yet been identified, but also of shellfish . In addition, there were large numbers of monocotyledons , more precisely the fibers of their rhizomes . However, the most common were pond rush fibers . Quinoa, however, was only found in one case, possibly also the potato.

Ethnic diversity, fishing and farming cultures in the north, hunters in the south

Around 80,000 indigenous people lived in northern Chile at the time of the Spanish conquest . The deserts near the coast of northern Chile were populated by the nomadic Chango . They went out to sea on canoes covered with sealskin to fish; The menu was also supplemented with crabs, game, seeds, berries and nuts. The sedentary Aymara lived inland . In the canyons on the Altiplano , they dug irrigation ditches to grow corn, kidney beans, quinoa (a type of grain) and pumpkin. On the Altiplano, they grew potatoes and raised llamas . It is believed that the Aymara formed the Tiahuanaco culture. Around 1500 they had to submit to the Inca , but retained a certain autonomy. The Atacameño lived a very similar way of life in the canyons of the Andes. In the semi-arid north of Chile, the sedentary Diaguita lived by permanent streams, where they developed an agriculture similar to the Aymara.

The auraucan peoples (Picunche, Mapuche, Huiliche, Pehuenchen and Cuncos) lived in the fertile and climatically favored central Chile, who had the same language but different ways of life. At the time of the Spanish conquest, between 0.5 and 1.5 million indigenous people lived in this region. The Picunche lived in large permanent villages. They built smaller irrigation canals to intensify agriculture. The Mapuche and Huilliche, on the other hand, lived in small settlements in river valleys. They burned down a small piece of forest near the settlement ( slash and burn ) to grow corn, kidney beans, quinoa, pumpkin, chilli and white potatoes. As a result of the slash and burn, the soil was enriched with nutrients and the sunlight was able to penetrate to the ground. After three to four years the soil was exhausted, so that the settlers had to move on ( shifting cultivation ). They also raised llamas for meat and wool. There was also a highly developed pottery and textile weaving mill. The Cuncos populated a coastal area and the island of Chiloe. They lived mainly from fishing and catching crabs. The Pehuenchen lived nomadically, they collected the nuts of the Chilean araucarias and hunted guanacos, from whose skins they made their clothes. The name Pehuenche means auraukarium nut people.

The south of Chile ( Patagonia ) was sparsely populated. Nomadic hunters and gatherers who used canoes lived on the fjords and rivers . These include the Chonos , Kawesqar and Yámana , who differ from one another in language and culture.

In contrast to the Europeans, the indigenous peoples do not use metals on a larger scale for making tools, but mainly for making jewelry. Animal labor was also used to a much lesser extent. Llamas were only used as a means of transport on the Andean trails. Wherever possible, the indigenous people preferred to transport their goods in canoes.

Among the cultivated plants, maize was of particular importance as it was one of the few foods that could be stored for several years. Therefore, the indigenous people accepted that complex terraces and irrigation systems had to be built for its cultivation in the Andes. On the basis of necklaces made of bones, gold and copper pieces, a certain social hierarchy is inferred.

Inca

The Inca origin was in what is now Peru . Probably 70 years before the arrival of the Spaniards, the Inca under Túpac Yupanqui (1438–1491) began to conquer northern Chile as far as the Río Maule . The main settlements were on the rivers of Aconcagua , Mapocho and Maipo , Quillota in the valley of the Aconcagua is possible as the southernmost settlement . In 1563 Santillan sees the southern border on the Rio Cachapoál south of Santiago. José Toribio Medina reported in 1882 about a fortress ruin on Cerro de la Angustura. A further expansion failed due to the determined resistance of the Auraucan tribes in the battle of the Maule, which lasted several days and is mentioned in Spanish sources, for example in the work of Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (Libro 2, Cap. 18-20), especially the Diaguita and Picuncha (The Spaniards called them “Promaucaes”) Central Chile was conquered, in the north the fighting was so fierce that some areas were temporarily depopulated. The influence of the Inca reached as far as bio-bio in the south.

The Inca left their religion and customs to the subjugated tribes, but demanded tributes in the form of metals (especially gold) and labor. Occasionally there were relocations. The rulers of the four parts of the empire bore the title Apukuna ("Lords"), Chile belonged to the partial empire Qullasuyu.

In the absence of money, trade and military alliances were based on the system of reciprocity . When the opponents voluntarily submitted, they were integrated into the ritual exchange system. Accordingly, the generous new masters expected, as a kind of gift in return, that the underdogs should build and fill storehouses to supply the capital; the local authorities were not disempowered, but strengthened to cooperate. The Inca moved local dignitaries to Cuzco , where their children were raised as Inca.

At the same time, indirect rule served to leave the distribution of work in the Mita system to the rulers of the individual ethnic groups. The principle of reciprocity was also used when the Inca state provided food, clothing, living space and tools for the conscripts as compensation for the obligations of the Mit'a and Mitmay , and organized ritual festivals at which not only the provincial nobility but also the communities were entertained . The mutual support in field work, called Ayni , still existed in rural areas in the post-colonial period and continues to this day. The vertical economy that existed before the Inca was also continued. She linked various usage zones with her respective products through family relationships. But a third of the area was used for the state and the Inca nobility and their bureaucracy, and another third for the clergy. Only the last third was available to the local subsistence economy. Individuals continued to own no land.

Chile as a Spanish colony

Spanish conquest (1541–1600)

The colonization of Chile did not take place directly through the Catholic Spanish crown, but rather with the help of Spanish explorers and adventurers like Pedro de Valdivia . It was he who founded today's capital Santiago de Chile as part of an expedition in 1541 . Another important city, La Serena , was also built by a Spanish explorer in 1544. However, it initially fell victim to an uprising by indigenous peoples, until La Serena was re-founded in 1549 and other cities in southern Chile a little later. This wave of founding came to a temporary end in 1553 after Valdivia's death, who fell in the Arauco War against the Mapuche. Due to the fighting and the organizational structures that went on until 1583, the Chilean colony developed into the most homogeneous and most centralized of the Spanish empire.

The original driving force behind the conquest of Chile was the procurement of gold as most of the European mines were depleted or inaccessible and the economy had seen strong expansion. Many of the Chilean deposits that were subsequently opened up and exploited by indigenous forced laborers, however, were exhausted after a short time. Remaining gold mines had to be abandoned as a result of the uprisings of the Auraucan peoples from 1599. For this reason, the colonizers were forced to live mainly from agriculture and cattle breeding from 1600 onwards. An exception was the Chiloé Archipelago , conquered in 1567, and its specialization in wood extraction from the Patagonian cypresses .

The Spanish colonization of America was marked by the establishment of cities in the center of the conquered areas. With the foundation of a respective city, some conquistadores became Vecinos , who received a building plot in the city and mostly a farm. Farms in the urban area (chacras) produced food, the more distant farms ( haciendas or estancias ) were mainly used for cattle breeding in the 16th century. In addition to the land, the conquistadors were also left as slaves to cultivate the land. This laid the foundation stone for Chile's economically and politically dominant landed property and the mass of agricultural workers with almost no rights for centuries. In addition to subsistence farming , Chile was also characterized by large-scale production (in haciendas or estancias) for export in the 16th century. The colonizers used the indigenous people as slave labor , but due to the poor living conditions, the indigenous population fell sharply. The Crown introduced the encomienda system to stop the worst excesses. But the settlers actually managed to continue slavery. Resistance to the exploitation came from Jesuits , officials and the Mapuche .

As a colony, Chile was also subject to the Spanish trade monopoly. Chilean foreign trade had to go through Peru, where transatlantic ship convoys were put together every year. The goods were then first brought to a Spanish monopoly port (first Seville, later Cadiz), and only there were they resold. So Spaniards and Peruvians could largely dictate the terms of trade. Foreign trade was associated with high costs for Chile.

Century of suet (1600–1687)

The destruction of the seven cities as part of the Arauco War meant for the Spaniards the loss of the two most important gold districts and many indigenous slave workers. In the following period, the Spanish settlement concentrated on the central zone around Santiago de Chile, which was increasingly explored, settled and economically exploited. As in the other Spanish colonies in America, agriculture and ranching became more important than mining over time. Mining was also less productive in the 17th century than in the 16th century and later from the 18th century. When the conquistadores realized that the Mapuche could not be subjugated for the foreseeable future, the enslavement of captured Mapuche was forbidden in 1683. With the decline of the indigenous population in the course of the 17th century, the importance of the encomienda system declined. In some cases, Indians were bought by the Huarpe people from what is now Argentina and brought over the Andes to work in Chilean haciendas.

Economic focal points in the Viceroyalty of Peru in the 17th century were the mining towns of Potosí (in today's Bolivia) and Lima (in today's Peru), while Chilean agriculture and animal husbandry played a subordinate role. The bulk of Chilean exports to the rest of the Viceroyalty consisted of beef kidney fat , charqui (dried meat) and leather . For this reason, the Chilean historian Benjamín Vicuña Mackenna called the 17th century the century of suet. Other export products were dried fruits, mules , wine and small amounts of copper. Trade with Peru was controlled by merchants from Lima, who enjoyed the protection of the local authorities. In addition to sea trade, there was also land trade from the port of Arica . Inner Chilean trade was insignificant as the cities were small and self-sufficient . The logging was of little importance in the colonial era. An exception was the Chiloé Archipelago , from where the Viceroyalty of Peru was supplied with boards made from the wood of Patagonian cypresses .

Century of Wheat (1687-1810)

In the period 1650–1800, the Chilean underclass grew considerably. Therefore the settlement policy was intensified. New villages and towns were founded and the surrounding land was distributed for cultivation. A settlement in the vicinity of the old cities ( La Serena , Valparaíso , Santiago de Chile and Concepción ) was preferred by settlers because there was a larger market there than in the new cities. The haciendas ( latifundia ) did not serve the local supply, but produced on a large scale for international export. After the earthquake of 1687 and a black rust epidemic in what is now Peru, Chilean grain exports to Peru began. These intensified in the period that followed, as the Chilean soil and climatic conditions for grain production were better than in Peru and the wheat was therefore cheaper and of better quality. The earthquake of 1687 also damaged wine growing in Peru for a short time, which led to wine growing in Chile.

The labor shortage in the haciendas ended around 1780, after which a population surplus emerged that could no longer find employment on the large estates. This “surplus population” settled partly in the outskirts of the big cities, partly they settled in the somewhat more northern part of Chile. There was also an expansion of mining. During the 18th century the annual gold production increased from 400 to 1000 kg and the annual silver production from 1000 to 5000 kg.

The shipbuilding industry in Valdivia peaked in the 18th century when numerous ships including frigates were built there. Other shipyards were built in Constitución and the Chiloé archipelago. For the Spanish crown, however, Guayaquil in today's Ecuador remained the most important shipyard in the Pacific region.

Direct trade with Spain via the Strait of Magellan or Buenos Aires began in the 18th century primarily as an export route for gold, silver and copper from Chilean mining. Since 1770 trade with the neighboring colonies of Peru and Ecuador declined. Instead, trade with Argentina, Paraguay, and Europe expanded. Spanish trade with the colonies came to a standstill at times due to international conflicts such as the American War of Independence and the Napoleonic Wars . In addition, the trade monopoly vis-à-vis the colonies was increasingly being undermined by smugglers from England , France and the United States . The Crown was forced to allow US flag vessels to fish in the Pacific. Under the pretext of buying provisions and having repairs carried out, these ships could legally stay in Chilean ports and secretly trade there.

Inner Chilean trade may not have been very important around 1800 either. There were hardly any developed roads, so the easiest transport and travel route were ship routes. In 1795 a road from Santiago de Chile to Concepción was completed, but it was initially little used.

The indigenous economies (Mapuche, Aymara, Quechua)

The Mapuche served up in the 16th century as hunter-gatherers, domesticated camelids and operated an extensive subsistence farming on Spent forest floor. The women now worked in the houses and made ceramics and textiles. This economy changed drastically through contact with the Spaniards. The colonial war that was imposed on them spawned a kind of war economy in which raids and robberies contributed significantly to the Mapuche economy. Horses played an important role in this, and horse breeding became a traditional part of their economy.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, a process called "Araucanization of the Pampas" began. The Mapuche became cattle breeders and developed a trading system on the Chilean-Argentine border. They even became Chile's leading horse and cattle traders. As a result, textile production also became a central factor, as well as basketry and ceramics, but above all silversmiths. These silver workers were called ngutrafe or retrafe . They achieved the highest expression of their art in the 19th century.

The defeat of 1881 put an end to this successful economy. The Indigenous Settlement Commission distributed the land in the form of now private, no longer collective land titles among a limited group of owners (títulos de merced). By 1900 the Mapuche were very impoverished, but used communal land rights, returned to subsistence farming, but kept their herds, albeit in a reduced form.

The few common economic activities included sharing the common harvest (mediería) and building a house ( mingaco ; 'to return the favor'), or to work together when many hands were required. However, their forests were decimated, hardly ever reforested, and the soil was gradually becoming depleted. In addition, separate communities formed through emigration, many of which consisted predominantly of men; This also led to family or individual integration into Chilean society and economy, so that most Mapuche today live in cities, apart from the elderly, who often stick to their accustomed way of life. The productive strengths are their work ethic, land ownership and their strong internal solidarity.

A different development took place among the Aymara . It is not only characterized by reciprocity , which is reflected in joint work ( Minka ), for example in cleaning the irrigation channels, but also by complementarity : They used different biotopes, each of which suggested a certain management. On the plateaus, it was only possible to keep livestock, such as llamas and alpacas, and recently also sheep. On fertile Andean slopes carried terrace cultivation . Agriculture and horticulture took place on the levels. Since different products were made in each of the biotopes, the Aymara exchanged these with one another. In the economy of the Aymara, rituals and symbols play a major role, which are supposed to keep life in a fragile balance.

The Quechua also worked according to the geographical zone in which they lived. Around Ollagüe and San Pedro de Atacama they devoted themselves to animal husbandry and limited farming. In addition to collecting, they also looked for minerals and metals while the communities in the Tarapacá region engaged in agriculture. The former worked on terraces in ravines that were less prone to frost, others grew potatoes and alfalfa . In the oases of Tarapacá, Mamiña, Quipisca and Miñe Miñe, the agricultural economy was very differentiated, so that in addition to potatoes and alfalfa, they grew maize, oregano and fruit. Some groups practiced subsistence farming, others sold part of the harvest, and still others almost the entire harvest. Only a few families around Ollagüe still practice transhumance ; migration to the cities is also pronounced here.

War of Independence and the Young Republic (1810–1873)

The wars of independence in Chile (1810-1818) and Peru (1809-1824) had a negative impact on the Chilean economy. The country was sacked by the armies and trading became a risky business. Peru, at that time the main buyer of Chilean export goods, remained under Spanish rule until 1824 and was therefore temporarily canceled as a trading partner for independent Chile. Chilean mining suffered relatively little damage.

During the War of Independence, the weapons needed could not be produced by the Chilean economy alone. Larger quantities had to be bought abroad. In addition to the Chilean army, the Chilean-Argentinian Andean Army had to be financed, as well as the expedition to liberate Peru . A loan of ₤ 1,000,000 was taken out in London in 1822 to finance the War of Liberation . This loan, along with its installments and interest, weighed heavily on the Chilean state. Finance Minister Diego José Benavente tried to make the tax system more productive, but met with resistance from citizens with many measures. Diego Portales Palazuelos offered to pay off the debt in return for granting a trade monopoly for tobacco , but the project failed because a monopoly could not be implemented in the chaotic post-war period.

When it gained independence, the Spanish trade monopoly fell; Chile opened its market to all nations from 1811 onwards. Foreign trade grew significantly. English, Italian, German and North American traders set up shop in Chile. Even after the independence of Peru, the Chilean-Peruvian trade did not regain its former importance, but trade with the United States , France and Great Britain increased sharply. Despite the basic free trade policy, domestic production was selectively protected by tariffs. The period from 1830 to 1870 was one of the fastest growing periods of the Chilean economy, mainly due to the booming silver mining industry and the resurgence of wheat exports. Silver deposits were discovered and mined from 1811 to the 1840s. Prosperous mining towns such as B. Copiapó . But the silver deposits were largely exhausted by the end of the 1840s. The mine owners who had become rich had accumulated a great deal of capital, which was invested in banks, agriculture, trade and commerce.

By overcoming the Spanish trade monopoly, Chile gained access to the Californian and Australian markets. As a result, wheat exports rose sharply. For their part, California and Australia experienced a gold rush in the middle of the 19th century, as a result of which numerous workers from agriculture and large parts of North America and Europe were lured into mining. As a result, the demand for wheat imports rose sharply. Chile was the only major wheat exporter in the Pacific at the time. The wheat boom did not last long, however, because with the end of the gold rush in the Pacific, wheat exports shifted to England in the 1860s. Between 1850 and 1875, the area on which wheat and barley was grown for export increased from 120 to 450 hectares. Chilean wheat exports fell sharply in the 1870s when agricultural production in the United States and Argentina became more productive due to increased technology and there was also competition from Russia and Canada .

By the middle of the 19th century, more than 80% of the Chilean population was employed in agriculture or mining.

Saltpetre era (1873-1914)

Even during the Saltpeter Republic there was an extremely pronounced, but not very efficient, large estate. By 1900 the haciendas owned 3/4 of the land, but only made 2/3 of the agricultural production. Agricultural export products were produced almost exclusively in haciendas. From 1873 Chile got into an economic crisis. Due to competition from more modern and efficient agriculture in Canada, Russia and Argentina, Chilean grain exports declined.

Silver mining income also fell. By the mid-1880s, the easily exploitable copper deposits were exhausted. Copper mining would have been possible at greater depths or with less valuable deposits, but this would have required major investments in modern technology. The Chilean mining companies avoided the risk and preferred to invest in the booming saltpetre industry (in Peru and Bolivia). Saltpetre production was less capital-intensive than modern copper mining, but it was more labor-intensive and higher profits could be expected with a lower investment risk. The world market share of Chilean copper production fell from 33 to 4% by 1911.

Contemporaries saw the economic crisis as the worst since Chile's independence. Mass corporate bankruptcies were expected. President Aníbal Pinto Garmendia said in 1878:

"Unless new deposits of natural resources are discovered or some other innovation of this kind occurs and the situation improves, then the crisis that has long been looming will worsen."

In the mid-1870s, Peru nationalized the nitrates industry, hurting British and Chilean interests. This procedure served as the occasion for the saltpeter war (1879–1883). By conquering Bolivian and Peruvian lands, Chile acquired most of the South American saltpetre and guano deposits - the latter was an important fertilizer - which led to renewed prosperity. The conquest of the saltpeter deposits is the main reason for the saltpeter war. Another response to the economic crisis was the conquest of Indian lands in the Región de la Araucanía . Great Britain had supported Chile financially and logistically in the saltpeter war. After the war the British share in the nitrates industry increased from 14 to 70%. The Chilean President José Manuel Balmaceda tried to exert state influence on the nitrate industry in order to increase the Chilean profit share from the mining of saltpeter and guano. As a result, Britain supported its political opponents, who overthrew him in the Chilean Civil War of 1891 . At the outbreak of World War I in nitrate export (wore Salpeterfahrten ) to 2 / 3 in the Chilean national income. The main customers were Europe, especially Great Britain and the German Empire. Saltpetre was used in Europe for the manufacture of artificial fertilizers and for the production of explosives .

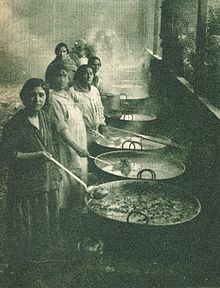

Between 1880 and 1910, the need for consumer goods for the growing urban population and the saltpetre workers increased sharply. The import of consumer goods increased by 250%, the import of machinery increased by 300%. In the 1870s, sugar factories, confectioneries, shoe and textile factories sprang up. Some economic historians conclude that Chile was on the way to becoming an industrialized nation even before 1914. Others see no industrialization yet, just a modernization process. By 1915, 7,800 mostly small factories had been set up, employing 80,000 workers and producing 80% of Chilean consumer goods. In terms of economic policy, a more mercantilist policy was pursued. In 1897 import tariffs on consumer goods were increased and tariffs on raw materials and machinery were reduced.

With the establishment of the Argentine railway line between Buenos Aires and Mendoza in 1885, cattle could be transported faster and more cheaply because a cattle drive was only necessary for the last stretch across the Andes. As a result, meat prices in Chile fell. The farmers then campaigned for the tariff on Argentine cattle to be increased. Such a law was finally passed by the Chilean parliament in 1897. The rise in the price of meat aroused resentment among the population, which led to demonstrations and unrest in Santiago de Chile in October 1905. Wine exports to Argentina increased after the inauguration of the Transand Railway in 1909, which simplified trade across the high mountain range. However, a free trade agreement negotiated between Chile and Argentina failed due to resistance from Chilean cattle breeders and Argentinian winemakers.

The extreme south also experienced an economic expansion in the late 19th century when a gold rush broke out on Tierra del Fuego in 1884, which also contributed to the growth of the regional metropolis of Punta Arenas . The sparsely populated Magallanes region was first used for sheep breeding in the 1880s.

The peso was subject to the gold standard in the second half of the 19th century . However, the gold standard was suspended during the economic crisis of the late 1870s and the Saltpeter War. To save the banks and to finance the war, a lot of paper money was printed, the monetary base increased significantly, and interest rates fell. This stimulated the economy. In the Chilean Civil War of 1891, the monetary base increased by 50% because President José Manuel Balmaceda had 20 million pesos printed in paper money. After the introduction of the nitrate tax, i.e. the tax on saltpeter exports, the government had a relatively rich source of tax at its disposal. From 1892 the adherents of the gold standard, the oreros , prevailed and Chile returned to the gold standard. The government took out a loan of 3 million pounds sterling to guarantee the exchange of paper pesos for gold. In the period that followed, 44 million paper pesos were exchanged for gold. However, the contraction of the monetary base caused a monetary debt crisis, which resulted in four banks going bankrupt. Shortly thereafter, border disputes with Argentina caused a costly arms race that depleted Chilean gold stocks. After the end of the arms race there was an economic crisis, the supporters of paper money, the papeleros, prevailed with the argument that paper money had to be issued again to support the economy and the banks. As a result, interest rates fell and the economy recovered, which the papeleros confirmed in their views. In the period that followed, additional paper money was issued more and more frequently. The economic recovery made it possible to return to the gold standard in 1918.

Crises and the beginning of industrialization (1914–1952)

The opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 caused a shift in maritime trade routes, which resulted in a sharp drop in traffic in the Chilean ports.

The First World War had a very strong economic impact on Chile. On the one hand, shipping traffic was hindered, on the other hand, all available capital in the European industrial countries was invested in the war industry, and the production of export goods declined. This caused exports and imports to decline worldwide. In addition, Chile raised its import tariffs by another 50 to 80% in 1916. Chilean industry was able to expand almost unhindered by foreign competition. By the end of the war (1918), Chilean industrial production rose by 53%.

Shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, the Haber-Bosch process was invented in the German Reich , so that Chile's nitrate was no longer required for the production of fertilizers and explosives. The enormous production of explosives during the war saved the Chilean saltpetre industry from collapse only for a short time; from 1919 onwards, saltpetre production gradually declined. The saltpeter developed into a resource curse for Chile . From 1914 the world market price for saltpeter fell, this reduced the income from the nitrate tax, which had previously generated half of the Chilean state income. When the volume of saltpeter exports also fell, government revenues fell dramatically. The government did not succeed in opening up sufficient new sources of taxation, and the state was financed to a large extent by issuing promissory notes, which increased inflation.

From 1922, however, copper mining began to expand, and in 1929 the value of copper exports already corresponded to the value of saltpeter exports. In 1937 copper exports made up 55% of total exports from Chile, while saltpeter exports only made up 18%. As early as 1912, the American Braden Copper Company, a company of the Guggenheim family , had introduced the flotation process in its Chilean copper mine El Teniente . Other American entrepreneurs invested significant capital in Chilean mines, which in turn contributed to the expansion of copper mining. The public reaction was mixed. On the one hand, the new production methods were less labor-intensive. Most of the sales from copper mining were spent on American machines and materials or distributed as surpluses to the American shareholders. The local economy benefited less from mining than before. It was exaggerated that mining would only create holes in Chile. Others praised the relatively good working conditions at American mining companies and the fact that without these companies there would have been no business activity in the region.

President Emiliano Figueroa Larraín took advice from the American economist Edwin Walter Kemmerer and reformed the tax system around 1926 to make it more efficient and productive. He created the Banco Central de Chile as an independent central bank . This allowed a return to the gold standard. Kemmerer then advertised Chile's creditworthiness at American banks. In the following years there was a sharp increase in capital imports from the USA, Great Britain, Switzerland and Germany.

The subsequent President Carlos Ibáñez del Campo used the opportunity to borrow money for his construction projects (railways, bridges, ports, etc.) in the USA. The policies of these two presidents in particular brought Chile apparent prosperity, but led to an awkward situation in the wake of the global economic crisis . The world economic crisis hit Chile, which was relatively well developed and prosperous by South American standards. The country was one of the hardest hit countries in the world. The decline in foreign trade by more than 90% (from 1929 to 1930) had fatal consequences for export-dependent agriculture and the global collapse in industrial production resulted in a sharp drop in demand for copper and saltpetre. Production in the mines had to be cut back and many workers were laid off. The unemployed miners migrated from the north to the south of Chile, where they could not find work. The weak exports meant that the loans taken out in the USA could no longer be serviced and there was no longer any money available for imports. Ibáñez tried at all costs to maintain the gold standard and to rehabilitate the state budget by cutting spending and laying off state employees. This made the crisis worse. When the gold reserves ran out in 1931, Chile had to give up the gold standard and declare its insolvency to the foreign lenders. When unemployment rose dramatically, riots broke out. Ibáñez then resigned on July 26, 1931 and fled to Argentina.

The deflation has been overcome yet in the course of the 1931st After a few short-lived governments, economic stabilization took place under President Arturo Alessandri . Most successful in the short term was the temporary tax exemption introduced in 1933 for construction projects that would be completed by 1935. This led to a strong recovery in the construction industry and a reduction in the number of unemployed. Structurally, economic policy changed insofar as mining and agriculture were no longer seen as the main engine of growth, but rather the still very small industrial sector. Business and the state switched to a strategy of import-substituting industrialization . In 1939, the Corporación de Fomento de la Producción (CORFO) was founded to specifically promote the economy, u. a. through technological research and the exploration of natural resources. The growth of the industrial sector made it possible to reduce mass unemployment again in the 1930s and 1940s. The number of people employed in industry doubled. Until the beginning of the 1950s, strong growth in the industrial sector ensured that the industrial goods that could no longer be imported due to the collapse of foreign trade could largely be produced domestically.

When world trade returned to normal in the 1950s, new problems developed. The stagnation of the export industry and agriculture resulted in trade deficits. The UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean , founded in 1948 with its seat in Santiago de Chile, tried to develop strategies against these problems under the influential General Secretary Raúl Prebisch ( structuralist economic policy ). In the 1950s and 60s, these strongly influenced the economic policy of a number of Latin American countries, including Chile.

Attempts to stabilize monetary policy (1952–1964)

An export-substituting economic policy continued under President Carlos Ibáñez del Campo . However, the strong expansion in demand was overshadowed by rising inflation and foreign trade deficits. Inflation raised the cost of living for citizens and the foreign trade deficits endangered the policy of export substitution, which required the purchase of machines and raw materials abroad. President Carlos Ibáñez therefore initiated a sharp cut in government spending and a markedly contractionary monetary policy. The resulting recession led to a partial withdrawal of the measures.

In keeping with the Keynesian strategy, President Jorge Alessandri tried to limit state interventions largely to fiscal policy in order to stimulate economic growth through a climate of investment confidence and confidence. He tried to stabilize monetary policy, in particular by pegging the peso to the dollar , as well as liberalizing foreign trade. Thanks to the dollar peg, it was possible to substantially reduce inflation between 1960/61, but the foreign trade deficits increased, which resulted in a currency crisis . In 1962 the peso had to be devalued and the political measures reversed. The inflation rates rose again to the previous level. Investment increased, but while the industrial sector grew, the agricultural sector stagnated.

Structural reforms

Presidency of Frei Montalva (1964–1970)

President Eduardo Frei Montalva , elected in 1964, initiated a tax reform in 1965 that reduced tax avoidance and evasion and significantly increased tax revenue. Public financing by issuing new promissory notes was cut back. The value of the peso was supported by an exchange rate peg with moving parities . This turned out to be at least less damaging to the export industry than a fixed exchange rate peg and, by overvaluing the peso, allowed relatively cheap imports of the necessary machinery and raw materials. Very sharply rising wages partially thwarted the monetary stabilization policy, but despite the rise in inflation, there was also a sharp rise in real wages during this period. Industrial development was driven by state investments, especially in the telecommunications sector and in the petrochemical industry. The agricultural sector saw the first signs of land reform . The process of nationalization of the mostly foreign-owned copper mines began under Frei Montalva. By 1970, the proportion of Chilean ownership in Chilean copper mines had risen to 51%.

Allende Presidency (1970–1973)

President Salvador Allende attempted an aggressive expansion strategy. Government spending and wages rose sharply. Due to an underutilization of the economy, politics caused economic growth of 8% in 1971 without inflationary pressures. In the period that followed, however, overall economic demand rose much faster than production capacities, as the investment quota fell. There were macroeconomic imbalances due to high government budget deficits, a sharp increase in the money supply and hyperinflation . This reduced economic growth in 1972, and in 1973 production even decreased by 4%.

Under Allende, land reforms were pushed ahead and the nationalization of copper mines in foreign ownership was completed. There were also attempts to nationalize banks. However, the nationalization of American copper mines without compensation led to a political conflict with the USA, under whose pressure the Inter-American Development Bank , the World Bank and American banks stopped lending to Chile. However, loans were still granted by some institutions and the like. a. awarded by the International Monetary Fund .

With the system developed by Stafford Beer consisting of a supercomputer and connected teleprinter called Cybersyn , Allende tried to centrally coordinate the decision-making of state, nationalized and private companies. Managers could use it to send production capacities, bottlenecks and other information to the government. The information was then evaluated by the government. After the military coup, there was no longer any interest in coordinating the economy and thus no longer in CyberSyn.

Aftermath of the reforms

The lasting effects of the economic policy under Eduardo Frei Montalva and Salvador Allende include land reforms and the nationalization of the copper mines. The latter remained state-owned under the aegis of the Chicago Boys , were grouped under one company as Codelco and still make a major contribution to public financing today (Codelco, for example, contributed 20% of state revenue in the mid-1980s, in 2004 it always was still 14%). Furthermore, a policy of export diversification began under Eduardo Frei Montalva, which later governments continued.

“Neoliberal Reforms” under General Pinochet

Radical Reforms (1973–1982)

After the coup in September 1973 , all important ministries were initially headed by the military. From September 1973 to April 1975, the regime, led by Augusto Pinochet , essentially reversed Allende's economic policy decisions by lowering tariffs, freeing up prices, devaluing the currency and privatizing state-owned companies. The regime was politically divided. Some generals, called duros , advocated an authoritarian corporatism in the style of Spanish Franquism . Another group were the blandos , who did not strive for a permanent military dictatorship, they supported the Chicago Boys.

Monetarian shock therapy

By the end of 1974, the most important ministries were occupied by economists who had studied at the University of Chicago and were therefore known as the Chicago Boys . According to the monetarist theory taught at the University of Chicago of the 1970s, it was assumed that moderate growth in the money supply could ensure constant economic growth and low inflation. A rather restrictive monetary policy was therefore at the center of economic policy considerations. The Chicago Boys' role models were Milton Friedman and Friedrich August von Hayek , a representative of the Austrian school . General Pinochet thus preferred the monetarist ideology of the Chicago School to the ideology of structuralism that had been traditional in Latin America until then and to a nationalist economic policy of the duros. The theoretical program of the Chicago Boys had already been put together before Pinochet came to power under the name El ladrillo (Spanish for the brick). Under the conditions of the military dictatorship, this technocratic-rigid program could be implemented regardless of the citizens and most economic interests.

This first generation of Chicago Boys consisted of hardliners. On Friedman's advice, they conducted monetarist shock therapy . To reduce inflation, government spending was cut by 27% and tariffs were cut from 70 to 33%. The central bank raised interest rates from 49.9 to 178%. The consequence, predicted and accepted as inevitable, was the 1975 recession, which caused gross domestic product to shrink by 15% at its lowest point. Real wages fell by around 60% and unemployment doubled. In the short term, 210,000 people were employed in public work programs. As part of a radical tax reform, wealth and capital gains taxes were abolished. The corporation tax was lowered, this was financed by the introduction of the value added tax . The bottom line was that higher incomes and assets were relieved at the expense of lower incomes and assets.

The inflation rates fell significantly until 1981, but remained in double digits:

| year | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 | 1977 | 1978 | 1979 | 1980 | 1981 | 1982 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflation (%) | 508.1 | 376.0 | 340.0 | 174.0 | 63.5 | 30.3 | 38.9 | 31.2 | 9.5 | 20.7 |

"Seven modernizations"

In 1979, the Chicago Boys expanded their economic policy program to include the seven modernizations in labor, social security, education, health, justice, agriculture and regional administration. In labor market policy , efforts were made to equate human labor with a commodity. Unions were banned in 1973 and unionists have been politically persecuted ever since. In 1979, the formation of local unions was allowed again, but the right to strike was severely restricted. Health and safety laws have been abolished or weakened across the board. The health policy was to replace the public health insurance through private health insurance. The Chilean pension system has also been redesigned to replace public pension insurance with private pension insurance. In the education system and the judiciary, government spending was cut and some services were privatized. The military and police, who made up a large part of the dictatorship's staff, kept their state pension systems (until today).

Compared to 1970 ( before Allende's reforms) in 1975 spending on health was 33% lower, education 37% lower, housing 26% lower and insurance 39% lower. The dictator's new priorities become clear: instead of 59% (1970), the state spent only 32% of state funds on social issues in 1975. In 1980 (seven years after the coup) wages were 17% lower than before Allende.

The sharp recessions and reforms led to widening poverty and income inequality:

|

|

The suppression of the trade unions led to falling real wages and thus a sharp internal devaluation , which led to a decrease in export prices and a relative increase in the cost of imports. This, together with the decline in domestic demand, led to an export boom.

Due to the high number of corporate insolvencies, the share of the industrial sector in value added fell significantly. The Chicago Boys argued that these companies had only emerged as a result of the previous governments' economic policies ( protective tariffs as part of the strategy of import-substituting industrialization) and were not productive enough to survive in free world trade. The economist Ricardo Ffrench-Davis counters that the large number of bankruptcies are not necessarily due to a lack of competitiveness. The recessions of 1973 and 1975 as well as real interest rates averaging 38%, rapid liberalization of foreign trade and the exaggerated appreciation of the peso around 1980 were the decisive factors that caused great problems for Chilean companies.

The Chicago Boys privatized many state-owned companies. The companies were sold almost exclusively to large corporations and conglomerates that had good relationships with individual Chicago Boys. The companies were sold very cheaply, on average 30% below the respective company value. With the privatizations and laissez-faire tendencies in economic policy from 1975 to 1982, the economy experienced a strong concentration. The trend that has existed for decades to forge conglomerates and corporations (Grupos económicos). that were economically independent and politically influential (this was how the grupos survived the left UP government without damage), grew stronger in these years. In 1978, five groups controlled more than half of the 250 most important private companies, often through bank holdings. The copper mines were not privatized, however. The US mining companies were compensated for the expropriation that took place under Allende, but the operations remained state property. These state-owned enterprises were of very great financial importance; in 1982 alone, the profit distributed to the state corresponded to 25% of the gross domestic product. Extensive land reforms had been carried out under Frei and Allende , in which 40% of the cultivated area was redistributed and the previous owners were compensated. Pinochet gave back 29% of the expropriated land and ended cultivating cooperatives. Most of the distributed land was not returned to the often unproductive hacendados . That is why there is still a large sector of very efficiently working medium-sized farms (20-100 ha) in Chile. The regime cut subsidies and opened the markets to the world market. As a result of this abrupt, undamped shock, agricultural production fell for eight years.

From 1977 to 1980 there was an economic boom, which was, however, also driven by a real estate bubble and high foreign debt. The success of the reforms initially seemed to be confirmed. Alongside Margaret Thatcher's reforms, the Chilean experiment had become a showpiece for monetarists and market liberals. Friedman coined the expression miracle of Chile in his regular column in Newsweek on January 25, 1982 , when he described the development there as an "economic miracle".

1981/82 crisis

External triggers of the crisis were the high interest rate policy of the United States and the oil crisis. With the appointment of Paul Volcker as head of the Fed in 1979, a phase of monetarist disinflationary policy and thus high interest rates began in the USA . Since most of the Chilean foreign debt was floating rate, not only did new loans become heavier, but the overall interest burden. At the end of 1979 the Iranian Revolution caused the second oil price shock , which hit the oil importing country Chile on the one hand and drove the most important export markets into recession on the other. So the demand and the price of copper and other export products fell. The copper price fell by 17.5%. These external causes led to economic crises ( Latin American debt crisis ) in most Latin American countries .

Due to internal reasons, the crisis of 1981/82 in Chile was considerably more severe than in most Latin American countries. The structural reason for Chile's crisis lay in the exorbitant private foreign debt. In 1979 the Chicago Boys pegged the value of the peso to the US dollar ( fixed exchange rate ) to combat inflation . This led to a strong appreciation of the peso, which made exports more expensive and imports cheaper. This was exacerbated by the reduction in customs tariffs. The natural consequence were trade deficits . In the course of the debt crisis, the trade deficits had to be reduced significantly, so in 1982 the peso was devalued by 70%. This led to a sharp increase in the real interest rate on foreign currency loans , which in turn led to a deep recession. The deregulation of financial markets and the abolition of capital controls have also contributed to this crisis . The Chicago Boys were wrongly of the opinion that a currency crisis could only arise through government intervention and not through uninfluenced decisions by companies and citizens. Thanks to the capital market, the banks had borrowed heavily at variable interest rates abroad and were lending the capital in Germany. Then when the peso depreciated and interest rates rose, the banks ran into financial difficulties. Investors withdrew their portfolio investments for a short time and thus intensified on the one hand the devaluation and on the other hand the capital shortage of the banks. The banking crisis intensified the economic crisis.

The consequence of the crisis was that economic output fell by 14.2% in 1981 and unemployment rose to 30% in the following year. A third of the population was malnourished. In 1982 there were “hunger marches” and days of protest (Dias de protesta) in many cities . Their demand was: "Bread, work, justice and freedom" . Many observers expected Pinochet to fall. But this was prevented by the declaration of a state of emergency in 1983.

The economic and financial crisis has now turned the international assessment of economic reforms among the Chicago Boys. The development was no longer described as an economic miracle, but as a failure, even a debacle. In 1982/83 the Chicago Boys were replaced by Praktiker.

In response to the crisis, a gradual competitive devaluation of the peso was permitted and some import duties were increased. To curb the credit crunch and bank runs , the two largest banks were taken over by the state in 1982. In 1983 five more were nationalized and two more came under state supervision. In order to reassure international lenders, the central bank had to pay for the foreign debt. As a result, the state quota rose to over 34% and thus far higher than under the socialist Allende. Critics mocked this development as the "Chicago way to socialism".

"Pragmatic Neoliberalism" (1983–1990)

With Hernán Buchi , who at the Columbia University in New York had studied a pragmatic Chicago Boys in 1985 as finance minister. Büchi had no inhibitions about optimizing the market economy through state intervention. A new financial crisis should be avoided through banking regulation and the newly established banking supervision Superintendencia de Bancos e Instituciones Financieras (SBIF) as well as capital controls. The ProChile export promotion program was launched to overcome the shortage of foreign exchange . To this day, it offers Chilean entrepreneurs practical and concrete assistance, for example with information about the peculiarities of the target markets. A further diversification and an increase in exports could be achieved through discounted credits and subsidies for the export industries. The import duties have been differentiated and individual duties have been raised to up to 35%. Minimum prices have been guaranteed for individual agricultural products. The banks nationalized during the economic crisis and some profitable state-owned companies were privatized. In contrast to the 1970s, monetary policy was limited to a moderate, classic interest rate policy, with double-digit inflation rates being accepted. Since the mid-1980s, the economy has grown by an average of 7.9% annually

Income inequality also increased in the second half of the 1980s, and the proportion of the population below the poverty line only fell slightly. When Pope John Paul II visited Chile in 1987, he addressed the "drama of extreme poverty" and urged the Chileans to take quick and effective action in favor of the poor, as they cannot wait for a general improvement in prosperity for brings relief to the poorest.

Aftermath of the reforms

According to Anil Hira, the most important lasting effect of the Chicago Boys' economic policy is its contribution to the maturation of the Chilean capital market. Since 1985, Chile’s economic savings have risen sharply. More investment has been made and Chile has become less dependent on foreign credit. The increase in the national saving rate was by some economists as a direct consequence of the introduction of the funded system as part of the Chilean pension reform considered. Due to the Latin American debt crisis , it was very difficult to obtain foreign loans in the 1980s. Many Latin American countries have therefore tried similar pension reforms to increase domestic capital accumulation and thereby stimulate higher economic growth. However, a slight increase in the macroeconomic savings rate in coincidence with the pension reform could only be observed in Peru. In Argentina there was no change in the savings rate as a result of the pension reform. In Colombia and Mexico, the macroeconomic savings rate even fell after the introduction of the funded system. On closer inspection, the simple formula of the funded procedure = higher economic savings was based on a mistake in reasoning. For example, contributions to the Chilean pension funds in 1988 amounted to 2.7% of the gross national product, which had increased private savings accordingly. However, economic observers had overlooked the fact that conversion costs of around 4% of the gross domestic product were incurred at the same time, which had reduced public savings accordingly. Overall, contrary to initial assumptions, the change in the pension system did not have a positive, but rather negative effect on the Chilean savings rate. Peter R. Orszag and Joseph E. Stiglitz come to the conclusion that the introduction of a funded system does not in itself lead to an increase in the economy-wide savings rate; this depends on the further behavior of the citizens and the state. Against this background, it should be noted that reforms were carried out in other economic areas in Chile in the 1980s, which led to a maturation of the Chilean capital market and to strengthening of confidence in institutions of the Chilean capital market as well as to an increase in the willingness to save and invest to have. With regard to the core functionality of a pension system to secure the supply of the population, the privatization of the pension system had very negative consequences. Since the privatization of pension insurance, half of the Chilean population have no longer acquired any pension rights and for 40% of the other half of the population it has become difficult to at least meet the requirements for a minimum pension.

The radical market reforms of the Chicago Boys led to mass unemployment and a loss of purchasing power. The standard of living of many Chileans has deteriorated drastically. As a result, in the phase of pragmatic neoliberalism, Pinochet relied on economists who were at greater distance from Milton Friedman's economic model. It was not until after the crisis of 1981/82 that the doctrine of the Chicago Boys was abandoned , with re-regulations, cautious state interventions and to support important bankrupt companies, the economy got on a sustainable growth path.

Even after democratization, the strategy of an export-oriented economic policy and relatively low tax rates introduced by the Chicago Boys was pursued. Their successes were small, because an average economic growth of 2.9% was rather average in international comparison and was even low by Chilean standards. According to Ricardo Ffrench-Davis , advisor to the UN Economic Commission for Latin America , economic development remained well below growth potential both in Allende's reign and in that of Pinochet. Average wages fell during the Chicago Boys' tenure; the proportion of Chileans living below the poverty line also increased from 20 to 44%. Ffrench-Davis attributes these negative effects to the harmful radicalism of the shock therapy in question.

Economic policy after speech democratization (since 1990)

Setting the course during the transition

In the last months of the dictatorship the regime tried to establish the economic order. The central bank was granted independence and its president was to be determined by the military. In the phase of transition to democracy , the Concertación governments had to remain considerate of the military, with an implicit agreement with the military not to make any significant changes in economic policy. In particular, the export-oriented economic policy was continued. In social policy there was a tentative increase in social spending. The distribution of income , which had become extremely uneven since the reforms under Pinochet, converged very much in the first years after democratization. To reduce poverty, the government significantly increased social spending, particularly in the housing, education and health sectors.

| 1960 | 1965 | 1970 | 1974 | 1980 | 1985 | 1988 | 1992 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13.6 | 12.9 | 11.5 | 15.2 | 10.9 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 16.1 |

| 1987 | 1990 | 1992 | 1994 | 1996 | 1998 | 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45.1 | 38.6 | 32.6 | 27.5 | 23.3 | 21.7 | 20.6 |

In 1990, in agreement between the government, employers and employees, labor law was reformed, in particular the rights of trade unions were strengthened in order to equalize the bargaining power of employers and employees. A tax reform increased income and increased the share of social spending in government spending. In 1991 it was decided to increase the minimum wage, which increased by 28% from 1989 to 1993. Further increases in the minimum wage were linked to progress in productivity. This also led to significant advances in the fight against poverty. While at the end of the Pinochet regime (1987) 45% of the population lived in poverty, in 2000 it was 21%. After 2000, Presidents Ricardo Lagos and Michelle Bachelet reformed the health system. The reforms have not prevented private health insurers from continuing to screen out citizens with low incomes or high risk of illness. However, the reforms ensured that certain diseases can be treated for every citizen. President Bachelet also pushed through the 2008 pension reform .

The strong inflow of foreign capital was regulated by a reserve requirement (indirect capital controls ). This ensured that a massive withdrawal of foreign capital would not cause a financial crisis so quickly. As a result, Chile was unable to infect the Mexican tequila crisis of 1994/95.

Under the presidents Patricio Aylwin (1990–1993) and Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle (1994–1999) Chile experienced the strongest period of prosperity in history with economic growth of 7% per year. The Chileans have been wealthier again than the average South American since the mid-1990s. The following table shows the economic development of Chile under Aylwin and Frei Ruiz-Tagle compared to the governments before:

| government | Alessandri (1959–1964) |

Frei-Montalva (1965–1970) |

Allende (1971–1973) |

Pinochet (1974-1989) |

Aylwin (1990-1993) |

Frei Ruiz-Tagle (1994-1999) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP growth in% | 3.7 | 4.0 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 7.7 | 5.6 |

| Export growth | 6.2 | 2.3 | −4.2 | 10.6 | 9.6 | 9.4 |

| Unemployment rate (employees in job creation measures were counted as unemployed) | 5.2 | 5.9 | 4.7 | 18.1 | 7.3 | 7.4 |

| Real wages (1970 = 100) | 62.2 | 84.2 | 89.7 | 81.9 | 99.8 | 123.4 |

| Investment rate in% of GDP (basis: peso from 1977) | 20.7 | 19.3 | 15.9 | 15.6 | 19.9 | 24.1 |

| Budget deficit or surplus as% of GDP | −4.7 | −2.5 | −11.5 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 1.2 |

Overcoming the Asian crisis

However , Chile was not immune to the Asian crisis . On the one hand, the economic stability at home and abroad, demonstrated in the tequila crisis, was overrated. Despite an extensive inflow of capital in 1996/97 (inflows of 10% of gross domestic product in 1997), capital controls were not tightened. In addition, the foreign trade deficit widened significantly in 1996/97.

In 1997 and 1998 there were severe economic crises in East Asia , Russia and Brazil . With the economic and currency crises in Southeast Asia, raw material exports collapsed into this region, which after all accounted for around a third of the export volume. Due to the currency devaluations there , the tiger states reduced the purchasing power for imports. In addition, the South American neighbors, which were an important trading partner and absorbed around a fifth of Chile's exports, were also dragged into the recession.

The Chilean central bank responded with a massive interest rate hike from 7 to 14% in order to reduce the capital outflow and stabilize the peso. In contrast to the rest of Latin America (especially Brazil), there were no major outflows in Chile. The rate hike, however, contributed to slump growth and unemployment in the short term. A short time later, interest rates were cut back to 5% and the government responded with Keynesian demand policies . For the first time in years, the national budget showed a deficit of 1.5% of gross domestic product . This enabled the economy to be stabilized. The economic consequences were serious, but not permanent. In 1999 the gross domestic product decreased by 1.1% and the peso depreciated by 16% against the American dollar.

Dependence on copper and diversification

The Concertación governments after 1990 also tried to diversify the Chilean economy by promoting innovation and research. The dependency on mining is still great. In 2010 mining generated 19.2% of the gross national product, 3.1% of the employees work in the economic sector. Agriculture generates 3.1% of the gross national product, 10.6% of the employees work here. Industry contributes 11.1% to the gross national product, 11.3% of the employees work here. The service sector contributes 66.5% of the gross national product, 75.1% of the employees work here. In addition to copper and lithium mining, food production, fish processing, iron and steel production, wood processing, the production of means of transport, cement production and the textile industry are the most important branches of the economy today. The Chilean government traditionally pursues an anti-cyclical fiscal policy . When the world market price for copper is high, the national budget generates surpluses; when economic growth is low, budget deficits are accepted . Chile reacted to the global economic crisis caused by the financial crisis from 2007 with an expansive fiscal policy and an expansive monetary policy .

literature

- Rebecca Storey, Randolph J. Widmer: The Pre-Columbian Economy . In: Victor Bulmer-Thomas, John Coatsworth, Roberto Cortes-Conde: The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America . Volume 1, Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 73-106.

- Augusto Millán: Historia de la minería del oro en Chile . Editorial Universitaria SA, 2001.

- Augustín Llona Rogríguez: Chilean Monetary History, 1860-1925. An Overview , in: Revista de Historia económica 15.1 (1997), pp. 125-160.

- Augustín Llona Rogríguez: Chilean Monetary History, 1860-1925 , Diss., Boston 1990.

- Gabriel Salazar, Julio Pinto: Historia contemporánea de Chile III. La economía: mercados empresarios y trabajadores . LOM Ediciones, 2002.

- Ricardo Ffrench-Davis : Economic Reforms in Chile. From Dictatorship to Democracy . University of Michigan Press, 2002.

- Gabriel Palma: Trying to 'Tax and Spend' Oneself out of the 'Dutch Disease': The Chilean Economy from the War of the Pacific to the Great Depression . In: Enrique Cardenas, Jose Ocampo, Rosemarie Thorp: An Economic History of twentieth-century Latin America , pp. 217–240.

- Juan Gabriel Valdés: Pinochet's Economists. The Chicago School of Economics in Chile , Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Gabriel Salazar: Labradores, Peones y Proletarios . 3rd edition, LOM Ediciones, 1985.

- Ricardo Camargo: The New Critique of Ideology. Lessons from Post-Pinochet Chile , Palgrave McMillan, 2013.

Web links

- Website Chile Precolombino of the Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino ( English or Spanish ) with articles on the economy of the indigenous people there

- Diana Seiler: Chile or the dictatorship of the free market , documentation, 3Sat, 52:45 min.

- Veit Straßner: Chile: Economy and Development. In: LIPortal , the country information portal .

Remarks

- ^ Anil Hira: Ideas and Economic Policy in Latin America. Praeger Publishers, 1998, ISBN 0-275-96269-5 , p. 14.

- ^ Helaine Silverman, William Isbell: Handbook of South American Archeology. Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-0-387-74907-5 , p. 61.

- ^ Helaine Silverman, William Isbell: Handbook of South American Archeology. Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-0-387-74907-5 , p. 67.

- ^ Nuria Sanz, Bernardo T. Arriaza, Vivien G. Standen (eds.): The Chinchorro culture. A comparative perspective, the archeology of the earliest human mummification , UNESCO, Paris 2014.

- ^ Helaine Silverman, William Isbell: Handbook of South American Archeology. Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-0-387-74907-5 , p. 55.

- ^ Helaine Silverman, William Isbell: Handbook of South American Archeology. Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-0-387-74907-5 , p. 45.

- ^ Helaine Silverman, William Isbell: Handbook of South American Archeology. Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-0-387-74907-5 , p. 54.

- ^ Helaine Silverman, William Isbell: Handbook of South American Archeology. Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-0-387-74907-5 , p. 46.

- ^ Helaine Silverman, William Isbell: Handbook of South American Archeology. Springer, 2008, ISBN 978-0-387-74907-5 , p. 53.

- ↑ Timothy G. Holden: Dietary evidence from the intestinal content of ancient humans with particular reference to desiccated remains from northern Chile. In: Jon G. Hather (Ed.): Tropical Archaeobotany. Applications and new developments. Routledge, London / New York 2013, pp. 74f.

- ^ Richard A. Crooker: Chile. Infobase Publishing, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4381-0492-8 , p. 33.

- ↑ James B. Minahan: Ethnic Groups of the Americas: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2013, ISBN 978-1-61069-164-2 , p. 46.

- ^ Richard A. Crooker: Chile. Infobase Publishing, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4381-0492-8 , p. 33.

-

^ Richard A. Crooker: Chile. Infobase Publishing, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4381-0492-8 , pp. 33-35.

Luis Otero: La huella del fuego: Historia de los bosques nativos. Poblamiento y cambios en el paisaje del sur de Chile. Pehuén Editores, 2006, ISBN 956-16-0409-4 , p. 36.

Tom Dillehay , Mario Pino Quivira , Renée Bonzani, Claudia Silva, Johannes Wallner, Carlos Le Quesne: Cultivated wetlands and emerging complexity in south-central Chile and long distance effects of climate change. In: Antiquity. Edition 81, year 2007, pp. 949–960. - ^ Sergio Villalobos: A Short History of Chile. Editorial Universitaria, ISBN 956-11-1761-4 , p. 16.

-

^ Sergio Villalobos, Osvaldo Silva, Fernando Silva, Patricio Estelle: Historia De Chile. 14th edition. Editorial Universitaria, 1974, ISBN 956-11-1163-2 , p. 57.

Richard A. Crooker: Chile. Infobase Publishing, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4381-0492-8 , p. 35. - ^ Rebecca Storey, Randolph J. Widmer: The Pre-Columbian Economy. In: Victor Bulmer-Thomas, John Coatsworth, Roberto Cortes-Conde: The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America. Volume 1, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-521-81289-5 , pp. 74, 75.

- ^ Rebecca Storey, Randolph J. Widmer: The Pre-Columbian Economy. In: Victor Bulmer-Thomas, John Coatsworth, Roberto Cortes-Conde: The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America. Volume 1, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-521-81289-5 , p. 83.

-

^ Sergio Villalobos, Osvaldo Silva, Fernando Silva, Patricio Estelle: Historia De Chile. 14th edition. Editorial Universitaria, 1974, ISBN 956-11-1163-2 , pp. 21-22.

Luis Otero: La huella del fuego: Historia de los bosques nativos. Poblamiento y cambios en el paisaje del sur de Chile. Pehuén Editores, 2006, ISBN 956-16-0409-4 , p. 36. - ↑ It is primarily the Chronicle of Garcilaso de la Vega from 1609 that provides most of the details of the Inca period. For him, the Río Maule is the southern limit of expansion. The reports of the Cieza de León of 1553 about the conquest campaigns of the Inca to Huayna Capac suggest that the armies advanced much further south; the historian Miguel de Olavarría reports in 1594 that the southern border was the Río Bío Bío, Diego de Rosales reports in 1670 that the Inca were as far as Concepción and after Fernando de Montesinos even as far as the Magellan Strait (Tom D. Dillehay, Américo Gordon: La actividad prehispánica y su influencia en la Araucanía , in: Tom Dillehay, Patricia Netherly (eds.): La frontera del estado Inca , 2nd edition, Quito 1998, pp. 183–196, here: pp. 185 f.).

- ↑ Garcilaso de la Vega: Primera parte de los commentarios reales. Quetretan del origen de los Yncas… , Lisbon 1609 ( digitized , PDF, 545 pages).

- ↑ Tom D. Dillehay, Américo Gordon: La actividad prehispánica y su influencia en la Araucanía , in: Tom Dillehay, Patricia Netherly (ed.): La frontera del estado Inca , 2nd edition, Quito 1998, pp. 183-196 ( online , PDF).

- ^ Sergio Villalobos: A Short History of Chile. Editorial Universitaria, ISBN 956-11-1761-4 , pp. 22-23.

- ^ Hermann Boekhoff, Fritz Winzer (ed.): Cultural history of the world . Braunschweig 1966, p. 559

- ↑ Alvin M. Josephy: America 1492 - The Indian peoples before discovery , Frankfurt 1992, p. 283.

- ↑ Hans-Joachim Löwer: We have not died yet - Inka, Maya, Azteken - Einst-Jetzt , Nürnberg 1992, p. 214.

- ^ Sergio Villalobos, Osvaldo Silva, Fernando Silva, Patricio Estelle: Historia De Chile. 14th edition. Editorial Universitaria, 1974, ISBN 956-11-1163-2 , p. 87.

- ^ Sergio Villalobos, Osvaldo Silva, Fernando Silva, Patricio Estelle: Historia De Chile. 14th edition. Editorial Universitaria, 1974, ISBN 956-11-1163-2 , pp. 97-99.

- ↑ James B. Minahan: Ethnic Groups of the Americas: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2013, ISBN 978-1-61069-164-2 , p. 97.

- ↑ a b Simon Collier, William Sater: A History of Chile, 1808-2002. Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-521-53484-4 , p. 7.

- ↑ Fernando Torrejón, Marco Cisternas, Ingrid Alvial, Laura Torres: Consecuencias de la tala maderera colonial en los bosques de alece de Chiloé, sur de Chile (Siglos XVI-XIX). In: Magallania. Edition 39 (2), 2011, pp. 75–95.

- ^ Sergio Villalobos, Osvaldo Silva, Fernando Silva, Patricio Estelle: Historia De Chile. 14th edition. Editorial Universitaria, 1974, ISBN 956-11-1163-2 , pp. 109-113.

- ^ Sergio Villalobos: A Short History of Chile. Editorial Universitaria, ISBN 956-11-1761-4 , p. 39.

- ^ Sergio Villalobos: A Short History of Chile. Editorial Universitaria, ISBN 956-11-1761-4 , p. 40.

- ↑ Gabriel Salazar: Labradores, Peones y Proletarios. 3. Edition. LOM Ediciones, 1985, ISBN 956-282-269-9 , pp. 23-25.

- Jump up ↑ Simon Collier, William Sater: A History of Chile, 1808-2002. Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-521-53484-4 , pp. 15-16.

- ^ Gabriel Salazar, Julio Pinto: Historia contemporánea de Chile III. La economía: mercados empresarios y trabajadores. LOM Ediciones, 2002, ISBN 956-282-172-2 , p. 15.

- ↑ a b Sergio Villalobos, Osvaldo Silva, Fernando Silva, Patricio Estelle: Historia De Chile. 14th edition. Editorial Universitaria, 1974, ISBN 956-11-1163-2 , pp. 160-165.

- ^ Sergio Villalobos, Osvaldo Silva, Fernando Silva, Patricio Estelle: Historia De Chile. 14th edition. Editorial Universitaria, 1974, ISBN 956-11-1163-2 , p. 168.

- ↑ James B. Minahan, Ethnic Groups of the Americas: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, 2013, ISBN 978-1-61069-164-2 , p. 97.

- ^ Sergio Villalobos, Osvaldo Silva, Fernando Silva, Patricio Estelle: Historia De Chile. 14th edition. Editorial Universitaria, 1974, ISBN 956-11-1163-2 , pp. 166-170.

- ↑ a b Sergio Villalobos, Julio and Serrano Retamal Ávila: Historia del pueblo Chileno. Issue 4, 2000, p. 154.

- ↑ a b c Sergio Villalobos, Osvaldo Silva, Fernando Silva, Patricio Estelle: Historia De Chile. 14th edition. Editorial Universitaria, 1974, ISBN 956-11-1163-2 , pp. 155-160.

- ^ Sergio Villalobos, Osvaldo Silva, Fernando Silva, Patricio Estelle: Historia De Chile. 14th edition. Editorial Universitaria, 1974, ISBN 956-11-1163-2 , p. 225.

- ↑ Gabriel Salazar: Labradores, Peones y Proletarios. 3rd edition, 1985, LOM Ediciones, ISBN 956-282-269-9 , p. 49.

- ↑ Gabriel Salazar: Labradores, Peones y Proletarios. 3rd edition, 1985, LOM Ediciones, ISBN 956-282-269-9 , p. 52.

- ↑ Gabriel Salazar: Labradores, Peones y Proletarios. 3rd edition, 1985, LOM Ediciones, ISBN 956-282-269-9 , p. 88.

- Jump up ↑ Simon Collier, William F. Sater: A History of Chile: 1808-2002. Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-521-82749-3 , p. 10.

- ^ Pablo Lacoste: La vid y el vino en América del Sur: el desplazamiento de los polos vitivinícolas (siglos XVI al XX). In: Revista Universe. 2004, Volume 19, Number 2, pp. 62-93.

- ↑ Gabriel Salazar: Labradores, Peones y Proletarios. 3rd edition, LOM Ediciones, 1985, ISBN 956-282-269-9 , pp. 153-154.

- ^ Sergio Villalobos, Osvaldo Silva, Fernando Silva, Patricio Estelle: Historia De Chile. 14th edition. Editorial Universitaria, 1974, ISBN 956-11-1163-2 , pp. 226-227.

- ↑ Isabel Montt Pinto: Breve Historia de Valdivia . Editorial Francisco de Aguirre, Buenos Aires-Santiago 1971, p. 55 .

- ^ Jorge León Sáenz: Los astilleros y la Industria Marítima en el Pacífico Americano: Siglos XVI a XIX. In: Diálogos, Revista Electrónica de Historia. 2009, Volume 10, Number 1, pp. 44–90, here p. 84.

- Jump up ↑ León Sáenz, Jorge: Los astilleros y la Industria Marítima en el Pacífico Americano: Siglos XVI a XIX. In: Diálogos, Revista Electrónica de Historia. 2009, edition 10, number 1, pp. 44–90, here p. 81.

-

^ Salazar, Gabriel, Julio Pinto: Historia contemporánea de Chile III. La economía: mercados empresarios y trabajadores. LOM Ediciones, 2002, ISBN 956-282-172-2 , pp. 16-17.