American mutilation of Japanese war dead

| Template:Wikify is deprecated. Please use a more specific cleanup template as listed in the documentation. |

During the World War II, some United States military personnel mutilated dead Japanese service personnel in the World War II Pacific theater of operations.

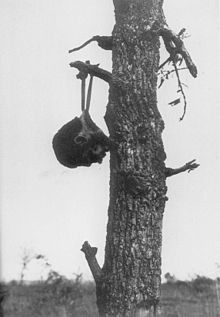

It has been claimed that most dead Japanese were desecrated and mutilated, for example by urinating on them or shooting the corpses, “re-butchering” them.[3] The mutilation of Japanese service personnel included the taking of body parts as “War Souvenirs” and “War Trophies” by U.S. service personnel. The most well known practice was the taking of skulls as trophies, although teeth were the most commonly taken object.

Trophy taking

In addition to trophy skulls, teeth, ears and other such objects, taken body parts were often modified, for example by writing on them or fashioning them into utilities or other artifacts.[4] "U.S. Marines on their way to Guadalcanal relished the prospect of making necklaces of Japanese gold teeth and "pickling" Japanese ears as keepsakes."[5] In an air base in New Guinea hunting the last remaining Japanese was a “sort of hobby”. The leg-bones of these Japanese were sometimes carved into letter openers and pen-holders.[4] An Australian turned a skull into a tobacco jar.[4]

In 1944 the American poet Winfield Townley Scott was working as a reporter in Rhode Island when a sailor displayed his skull trophy in the newspaper office. This led to the poem The U.S. sailor with the Japanese skull, which described one method for preparation of skulls (the head is skinned, towed in a net behind a ship to clean and polish it, and in the end scrubbed with caustic soda).[6] In October 1943, the U.S. High Command expressed alarm over recent newspaper articles, for example one where a soldier made a string of beads using Japanese teeth, and another about a soldier with pictures showing the steps in preparing a skull, involving cooking and scraping of the Japanese heads.[6] Charles Lindbergh refers in his diary to many instances of Japanese with an ear or nose cut off.[6] In the case of the skulls however, most were not collected from freshly killed Japanese, most came from already partially or fully skeletonised Japanese bodies.[6]

Extent of practice

The Allied practice of collecting Japanese body parts occurred on "a scale large enough to concern the Allied military authorities throughout the conflict and was widely reported and commented on in the American and Japanese wartime press."[7] The degree of acceptance of the practice varied between units. Taking of teeth was generally accepted by enlisted men and also by officers, while acceptance for taking other body parts varied greatly.[8]

The collection of Japanese body parts began quite early in the campaign, prompting a September 1942 order for disciplinary action against such souvenir taking.[8] Harrison concludes that since this was the first real opportunity to take such items (the battle of Guadalcanal), "Clearly, the collection of body parts on a scale large enough to concern the military authorities had started as soon as the first living or dead Japanese bodies were encountered."[8] When Charles Lindberg passed through customs at Hawaii in 1944 it was controlled if he was carrying bones.[vague] This was because of the large number of souvenir bones discovered in customs, also including “green” (uncured) skulls.[9]

On February 1, 1943, Life magazine published a famous photograph by Ralph Morse which showed the charred, open-mouthed, decapitated head of a Japanese soldier killed by U.S Marines during the Guadalcanal campaign, and propped up below the gun turret of a tank by Marines. The caption read as follows: "A Japanese soldier's skull is propped up on a burned-out Jap tank by U.S. troops." Life received letters of protest from mothers who had sons in the war and others "in disbelief that American soldiers were capable of such brutality toward the enemy." The editors of Life explained that "war is unpleasant, cruel, and inhuman. And it is more dangerous to forget this than to be shocked by reminders." Indeed, remarkably, Life received more than twice as many protest letters over a photograph of a mistreated cat in the same issue than they did over the photo of the severed head of the Japanese soldier.[10]

In 1984 Japanese soldiers remains were repatriated from the Mariana Islands. Roughly 60 percent were missing their skulls.[9]

Motives

Dehumanisation

In the U.S. there was a widely held view that the Japanese were sub-human.[11]. The U.S. media helped propagate this view of the Japanese, for example describing them as “yellow vermin”.[11]. In an official U.S. navy film Japanese troops were described as “living, snarling rats”.[12] The mixture of racism, dehumanizing propaganda, and real and imagined Japanese atrocities led to intense loathing of the Japanese.[11] "Marines did not consider they were killing men. They were wiping out dirty animals".[13]

The U.S. conviction that the Japanese were subhuman or animals, together with Japanese reluctance to attempt to surrender to allied forces, contributed to the fact that a mere 604 Japanese captives were alive in Allied POW camps by October 1944.[11] (For a discussion of Allied soldiers "standard practice"[14] of killing Japanese prisoners and Japanese attempting to surrender see Allied war crimes during World War II.)

Niall Ferguson states in Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War: "To the historian who has specialized in German history, this is one of the most troubling aspects of the Second World War: the fact that Allied troops often regarded the Japanese in the same way that Germans regarded Russians – as Untermenschen."[15] Since the Japanese were regarded as animals it is not surprising that the Japanese remains were treated in the same way as animal remains.[11]

Simon Harris comes to the conclusion in his paper “Skull trophies of the Pacific War: transgressive objects of remembrance” that the skull taking was the result of a society placing much value in hunting as a symbol of masculinity, combined with a de-humanisation of the enemy.

Brutalisation

Skulls were many times collected as souvenirs, also by non-combat personnel. They were proof of “having been there”.[16] Many writers and veterans have tried to explain the body parts trophy and souvenir taking by the brutalizing effects of a harsh campaign.[16]

While brutalization could explain part of the mutilations, this explanation does not explain the servicemen who already before shipping off for the Pacific proclaimed their intention to acquire such objects.[17] It also does not explain the many cases of servicemen collecting the objects as gifts for people back home.[17]

Harrison concludes that there is no evidence that the average serviceman collecting this type of souvenirs was suffering from "combat fatigue". They were normal men who felt this was what their loved ones wanted them to collect for them.[18]

U.S. reaction

“Stern disciplinary action” against human remains souvenir taking was ordered by the Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet as early as September 1942.[8] In October 1943 General George C. Marshall radioed General Douglas MacArthur about “his concern over current reports of atrocities committed by American soldiers”.[19] In January 1944 JCS issued a directive against the taking of Japanese body parts.[19]

Directives of this type were however only partially obeyed by commanders in the field, often “officers did not want to discourage expressions of animosity towards the enemy.”[8]

On 13 June 1944 President Roosevelt was presented with a letter-opener made out of a Japanese soldiers arm bone by Congressman Walter.[18] Roosevelt some weeks later, reacting to domestic and international criticism of trophy taking, returned the gift saying he did not want this type of object and recommended it be buried instead.[18]

Following the May 1944 Life Magazine publication of an American girl with her skull trophy the Army directed its Bureau of Public Relations to inform U.S. publishers that “the publication of such stories would be likely to encourage the enemy to take reprisals against American dead and prisoners of war.”[20]

Japanese reaction

News that president President Roosevelt had been given a bone letter opener by a congressman were widely reported in Japan. The Americans were portrayed as “deranged, primitive, racist and inhuman”. This reporting was compounded by the previous May 22, 1944 Life Magazine picture of the week publication of a young woman with a skull trophy.[21][22]

Hoyt in "Japan’s war: the great Pacific conflict" argues that the Allied practice of mutilating the Japanese dead and taking pieces of them home was exploited by Japanese propaganda very effectively, and "contributed to a preference to death over surrender and occupation, shown, for example, in the mass civilian suicides on Saipan and Okinawa after the Allied landings"[21]

War crime

Prompted by the publication of a skull trophy in Life Magazine in May 1944 a flurry of activity ensued.

In a memorandum dated June 13, 1944, the Army JAG asserted that such “such atrocious and brutal policies” in addition to being repugnant also were violations of the laws of war, and recommended the distribution to all commanders of a directive pointing out that “the maltreatment of enemy war dead was a blatant violation of the 1929 Geneva Convention on the sick and wounded, which provided that: After every engagement, the belligerent who remains in possession of the field shall take measures to search for wounded and the dead and to protect them from robbery and ill treatment.” Such practises were in addition also in violation of the unwritten customary rules of land warfare and could lead to the death penalty.[23]

The Navy JAG mirrored that opinion one week later, and also added that “the atrocious conduct of which some U.S. servicemen were guilty could lead to retaliation by the Japanese which would be justified under international law”.[23]

Context

The U.S. armed forces had a long history of brutality in the Pacific, beginning with the Philippine-American War, where military operations lasted until 1913.[24] All WWII remains discovered in the U.S. attributable to an ethnicity are of Japanese origins, none come from Europe.[4] The practice of taking skull trophies was resumed during the Vietnam War.

Some Japanese were also guilty of mutilating U.S. corpses, but this was neither as widespread as the American practice nor for the purpose of taking trophies.[25]

Contemporary

Skulls from the Vietnam War and from World War II keep turning up in the U.S.,[9] sometimes returned by former servicemen or their relatives, or discovered by police.[9] According to Harrison: Contrarily to the situation in average head-hunting societies the trophies do not fit in in the American society. While the taking of the objects was socially accepted at the time, after the war, when the Japanese in time became seen as fully human again, the objects for the most part became seen as unacceptable and unsuitable for display. Therefore in time they and the practice that had generated them were largely forgotten.

See also

References

- ^ http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3651/is_199510/ai_n8714274/pg_1 Missing on the home front, National Forum, Fall 1995 by Roeder, George H Jr

- ^ Lewis A. Erenberg, Susan E. Hirsch book: The War in American Culture: Society and Consciousness during World War II. 1996. Page 52. ISBN 0226215113.

- ^ Xavier Guillaume (July, 2003). "H-Net Review: Xavier Guillaume on The GI War against Japan: American Soldiers in Asia and the Pacific during World War II". H-Net.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Simon Harrison (2006). "Skull Trophies of the Pacific War: transgressive objects of remembrance". Journal of the Royal Antrophological Institute. 12: 826.

- ^ James J. Weingartner (February, 1992). "Trophies of War: U.S. Troops and the Mutilation of Japanese War Dead, 1941-1945". Pacific Historical Review. 61 (1): 556.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Harrison, p.822

- ^ Harrison, p.818

- ^ a b c d e Harrison, p.827

- ^ a b c d Harrison, p.828

- ^ http://www.rastko.org.yu/kosovo/istorija/ccsavich-propaganda.html War, Journalism, and Propaganda, An Analysis of Media Coverage of the Bosnian and Kosovo Conflicts, by Carl K. Savich

- ^ a b c d e Weingartner, p.54

- ^ Weingartner, p.54. Japanese were alternatively described and depicted as “mad dogs”, “yellow vermin”, termites, apes, monkeys, insects, reptiles and bats etc.

- ^ Weingartner, p.54 (in turn referenced to Rooney, The Fortunes of War (Boston, 1962), p. 37)

- ^ Niall Ferguson (2004). "Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War: Towards a Political Economy of Military Defeat". War in History. 11: 181.

- ^ Ferguson, p. 182

- ^ a b Harrison, p.823

- ^ a b Harrison, p.824

- ^ a b c Harrison, p.825

- ^ a b Weingartner, p.57

- ^ Weingartner, p.60

- ^ a b Harrison, p.833

- ^ The image depicts a young blonde at a desk gazing at a skull. The caption says “When he said goodbye two years ago to Natalie Nickerson, 20, a war worker of Phoenix, Ariz., a big, handsome Navy lieutenant promised her a Jap. Last week Natalie received a human skull, autographed by her lieutenant and 13 friends, and inscribed: "This is a good Jap – a dead one picked up on the New Guinea beach." Natalie, surprised at the gift, named it Tojo. The armed forces disapprove strongly of this sort of thing.

- ^ a b Weingartner, p.59

- ^ Renato Constantino. The Philippines: A Past Revisited. ISBN 971-8958-00-2.

- ^ Weingartner, p.62 (footnotes).

Further reading

- Paul Fussell "Wartime: Understanding and Behavior in the Second World War"

- Bourke "An Intimate History of Killing" (pages 37-43)

- Dower "War without mercy: race and power in the Pacific War" (pages 64-66)

- Fussel "Thank God for the Atom Bomb and other essays" (pages 45-52)

- Aldrich "The Faraway War: Personal diaries of the Second World War in Asia and the Pacific"

- Hoyt "Japan's war: the great Pacific conflict"

- Charles A. Lindbergh (1970). The Wartime Journals of Charles A. Lindbergh. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

External links

- One War Is Enough War Correspondent EDGAR L. JONES 1946

- American troops 'murdered Japanese PoWs'

- The US Sailor with the Japanese Skull by Winfield Townley Scott

- Eerie Souvenirs From the Vietnam War Washington Post July 3, 2007 By Michelle Boorstein]

- 2002 Virginia Festival of the Book: Trophy Skulls

- War against subhumans: comparisons between the German War against the Soviet Union and the American war against Japan, 1941-1945 The Historian 3/22/1996, Weingartner, James

- Racism in Japanese in U.S. wartime propaganda The Historian 6/22/1994 Brcak, Nancy; Pavia, John R.

- MACABRE MYSTERY Coroner tries to find origin of skull found during raid by deputies The Pueblo Chieftain Online.

- Skull from WWII casualty to be buried in grave for Japanese unknown soldiers Stars and Stripes

- HNET review of Peter Schrijvers. The GI War against Japan: American Soldiers in Asia and the Pacific during World War II.

- The May 1944 Life Magazine picture of the week (Image)