Lex Davison and Battle of Saint-Mihiel: Difference between pages

mNo edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox Military Conflict |

|||

'''Alexander Nicholas Davison''' ([[12 February]] [[1923]]–[[20 February]] [[1965]])<ref>[http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A130655b.htm Australian Dictionary of Biography Online Edition]</ref> was a racing driver who won the [[Australian Grand Prix]] four times between 1954 and 1961 and won the [[Australian Drivers' Championship]] in 1957. He drove [[Hersham and Walton Motors|HWM]]-Jaguar, [[Ferrari]], [[Aston Martin]] and [[Cooper Car Company|Cooper]]-Climax grand prix cars.<ref>[http://www.jagqld.org.au/Bulletin/bill_pitt.htm Bill Pitt's website]</ref> He died in a crash in practice for the 1965 International 100 at [[Sandown International Raceway]]. |

|||

|conflict=Battle of Saint-Mihiel |

|||

|image=[[Image:Battle of St. Mihiel 01.jpg|300px]] |

|||

|caption=American engineers returning from the St. Mihiel front |

|||

|partof=[[First World War]] |

|||

|date=[[12 September]]–19, 1918 |

|||

|place=[[Saint-Mihiel]] salient, [[France]] |

|||

|result=Allied victory |

|||

|combatant1={{flag|United States|1912}} <br> {{flag|France}} |

|||

|combatant2={{flag|German Empire}} |

|||

|commander1=[[John J. Pershing]] |

|||

|commander2=[[Georg von der Marwitz]] |

|||

|strength1=[[American Expeditionary Force]] <br> [[French Army]] |

|||

|strength2=[[German Fifth Army]] |

|||

|casualties1=7,000 |

|||

|casualties2=2000 dead and 5500 wounded <ref>Giese (2004)</ref> |

|||

|}} |

|||

{{Campaignbox Hundred Days 1918}} |

|||

The '''Battle of Saint-Mihiel''' was a [[World War I]] battle fought between September 12 - 15, 1918, involving the [[American Expeditionary Force]] and 48,000 [[France|French]] troops under the command of U.S. general [[John J. Pershing]] against [[German Empire|German]] positions. The [[United States Army Air Service]] (which later became the [[United States Air Force]]) played a significant role in this action. <ref>Hanlon (1998)</ref><ref>History of War (2007)</ref> |

|||

Davison was the father of Australian racing drivers Jon Davison and Richard Davison and grandfather of [[Alex Davison]], [[Will Davison]] and [[James Davison]]. |

|||

This battle marked the first use of the terms '[[D-Day]]' and '[[H-Hour]]' by the Americans, though it was not the first battle that the Americans were involved in despite popular belief to the contrary. <ref>Spartacus (2002)</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

<references/> |

|||

The attack at the St. Mihiel salient was part of a plan by Pershing in which he hoped that the U.S. would break through the German lines and capture the fortified city of [[Metz]]. It was one of the first US solo offensives in World War I and the attack caught the Germans in the process of retreating.<ref>History of War (2007)</ref> Hence their artillery was out of place and the Americans were more successful than they otherwise would have been. It was a strong blow by the U.S. and increased their stature in the eyes of the French and British forces. However, this battle again illustrated the critical role of artillery during World War I and the difficulty of supplying the massive World War I armies while they were on the move. The U.S. attack faltered after outdistancing their artillery and food supplies as muddy roads made support difficult.<ref>Giese (2004)</ref> The attack on Metz was not realized as the Germans refortified their positions and the Americans turned their efforts to the [[Meuse-Argonne offensive]]. <ref>Spartacus (2002)</ref> |

|||

{{start box}} |

|||

{{succession box | before = [[Doug Whiteford]] | title = Winner of the [[Australian Grand Prix]] | years = [[1954 Australian Grand Prix|1954]]| after = [[Jack Brabham]]}} |

|||

{{succession box | before = Inaugural | title = Winner of the [[Australian Drivers' Championship]] | years = 1957 | after = [[Stan Jones (auto racer)|Stan Jones]]}} |

|||

{{succession box | before = [[Stirling Moss]] | title = Winner of the [[Australian Grand Prix]] | years = [[1957 Australian Grand Prix|1957]] (with [[Bill Paterson (motorsport)|Bill Paterson]])<br/>and [[1958 Australian Grand Prix|1958]]| after = [[Stan Jones (auto racer)|Stan Jones]]}} |

|||

{{succession box | before = [[Alec Mildren]] | title = Winner of the [[Australian Grand Prix]] | years = [[1961 Australian Grand Prix|1961]]| after = [[Bruce McLaren]]}} |

|||

{{end box}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Davison, Lex}} |

|||

[[Image:General John Joseph Pershing head on shoulders.jpg|thumb|200px|right|General Pershing]] |

|||

[[Category:Australian racecar drivers]] |

|||

General John Pershing thought that a successful Allied attack in the region of St. Mihiel, [[Metz]], and [[Verdun]] would have a significant effect on the German army.<ref>History of War (2007)</ref> General Pershing was also aware that the area's terrain setting dictated that the "clearing" of the rail and road communications into Verdun, and therefore the loss of the German railroad center at Metz would be devastating to the Germans should the Americans capture it. After these goals were accomplished, the Americans could launch offensives into [[Germany]]. <ref>Hanlon (1998)</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:1965 deaths]] |

|||

=== Weather Reports === |

|||

{{Australia-sport-bio-stub}} |

|||

The weather corps of Corps I Operation Order stated: "Visibility: Heavy driving wind and rain during parts of day and night. Roads: Very muddy."<ref>Hanlon (1998)</ref> This would pose a challenge to the Americans when the order to advance was given. In some parts of the road, the men were almost knee-deep in mud and water. After five days of rain the ground was nearly impassible to both the American [[tanks]] and [[infantry]]. <ref>Giese (2004)</ref>Many of the tanks wrecked with water leakage into the engine, while others would get stuck in mud flows. Some of the infantry even developed early stages of trench foot, before the trenches were even dug. <ref>Spartacus (2002)</ref> |

|||

{{autoracing-bio-stub}} |

|||

DO A BURNOUT |

|||

=== German Defensive Positions === |

|||

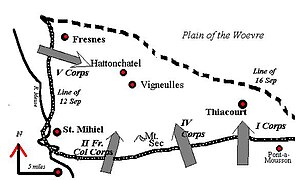

[[Image:Map of battle St. Mihiel.JPG|thumb|right|300px|Map of the Battle]] |

|||

Prior to the American operation, the Germans installed many in-depth series of [[trenches]], wire obstacles, and [[machine-gun]] nests.<ref>History of War (2007)</ref> The battlefields' terrain included the nearby premises of three villages: Vigneulles, Thiaucourt, and Hannonville-sous-les-Cotes. Their capture would accelerate the envelopment of the German divisions near St. Mihiel. The American forces planned to breach the trenches and then advance along the enemy's logistical road network. <ref>Hanlon (1998)</ref> |

|||

The Germans knew many details about the Allied offensive campaign coming against them. One Swiss newspaper had published the date, time, and duration of the preparatory [[barrage]]. However, the [[German army]] stationed in the area of St. Mihiel lacked sufficient manpower, firepower, and effective leadership to launch a counter-attack of its own against the Allies.<ref>Giese (2004)</ref> Thus, the Germans decided to pull out of the St. Mihiel salient and consolidate their forces near the Hindenburg Line. The Allied forces discovered the information on a written order to the German Group Armies von Gallwitz. <ref>Spartacus (2002)</ref> |

|||

Although the AEF was new to the French theater of war, they trained hard for several months in preparation of fighting against the German armies. Also, the British use of armor at the [[Battle of Cambrai]]<ref>History of War (2007)</ref> impressed General Pershing so much that he ordered the creation of a tank force to support the AEF's infantry. As a result, by September 1918, Colonel [[George S. Patton]] Jr. had finished training three tank brigades at [[Langres, France]] for an upcoming offensive at the St. Mihiel salient. <ref>Hanlon (1998)</ref> |

|||

== Aftermath == |

|||

General Pershing's operational planning of St. Mihiel separated the salient into several sectors. Each [[Corps]] had an assigned sector, by boundaries, that it could operate within. The American V Corps location was at the northwestern [[vertice]]s, the II French Colonial Corps at the southern apex, and the American IV and I Corps at the south-eastern vertices of the salient.<ref>Giese (2004)</ref> Furthermore, General Pershing's intent was obvious, to envelope the salient by using the main enveloping thrusts of the attack against the weak vertices. The remaining forces would then advance on a broad front toward the direction of Metz. This pincer action by the IV and V Corps was to drive the attack into the salient and to link the friendly forces at the French village of Vigneulles while the II French Colonial Corps kept the remaining Germans tied down. <ref>Hanlon (1998)</ref> |

|||

=== Explanation of Outcome === |

|||

One reason for the American forces success at St. Mihiel was General Pershing's thoroughly detailed operations order. General Pershing's operation included detailed plans for penetrating the Germans' trenches using a combined arms approach to warfare. <ref>History of War (2007)</ref>His plan had tanks supporting the advancing infantry, with two tank companies interspersed into a depth of at least three lines, and a third tank company in reserve. The result of the detailed planning was an almost unopposed assault into the salient. The American I Corps reached its first day's objective before noon, and the second days objective by late afternoon of the second. <ref>Spartacus (2002)</ref> |

|||

Another reason for the American success was the audacity of the small unit commanders on the battlefield. Unlike the World War One officers that commanded their soldiers from the rear, Colonel Patton and his subordinates would lead their men from the front lines.<ref>Giese (2004)</ref> They believed that a commander's personal control of the situation would help ease the chaos of the battlefield. <ref>Hanlon (1998)</ref> |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

* {{cite web|url=http://www.worldwar1.com/dbc/stmihiel.htm|title=St. Mihiel Offensive|last=Hanlon|first=Michael|date=1998|language=Egnglish|accessdate=2008-05-04}} |

|||

* {{cite web|url=http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/FWWmihiel.htm|title=St. Mihiel|publisher=Spartacus Educational|accessdate=2008-05-04}} |

|||

* {{cite web|url=http://members.aol.com/joeredone/mihiel.htm|title=Battle Analysis of St. Mihiel|last=Giese|first=Joseph|accessdate=2008-05-04}} |

|||

* {{cite web|url=http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_st_mihiel.html|title=Battle of St. Mihiel|last=Richard|first=J.|date=2007|publisher=History of War|accessdate=2008-05-04}} |

|||

==See also== |

|||

{{Commonscat|Battle of St. Mihiel}} |

|||

[[Category:Battles of the Western Front (World War I)|Saint-Mihiel]] |

|||

[[Category:Battles of World War I involving the United States|Saint-Mihiel]] |

|||

[[Category:Battles of World War I involving Germany|Saint-Mihiel]] |

|||

[[Category:Battles of World War I involving France|Saint-Mihiel]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[de:Schlacht von St. Mihiel]] |

|||

Revision as of 19:45, 10 October 2008

| Battle of Saint-Mihiel | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of First World War | |||||||

American engineers returning from the St. Mihiel front | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John J. Pershing | Georg von der Marwitz | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

American Expeditionary Force French Army | German Fifth Army | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 7,000 | 2000 dead and 5500 wounded [1] | ||||||

The Battle of Saint-Mihiel was a World War I battle fought between September 12 - 15, 1918, involving the American Expeditionary Force and 48,000 French troops under the command of U.S. general John J. Pershing against German positions. The United States Army Air Service (which later became the United States Air Force) played a significant role in this action. [2][3]

This battle marked the first use of the terms 'D-Day' and 'H-Hour' by the Americans, though it was not the first battle that the Americans were involved in despite popular belief to the contrary. [4]

The attack at the St. Mihiel salient was part of a plan by Pershing in which he hoped that the U.S. would break through the German lines and capture the fortified city of Metz. It was one of the first US solo offensives in World War I and the attack caught the Germans in the process of retreating.[5] Hence their artillery was out of place and the Americans were more successful than they otherwise would have been. It was a strong blow by the U.S. and increased their stature in the eyes of the French and British forces. However, this battle again illustrated the critical role of artillery during World War I and the difficulty of supplying the massive World War I armies while they were on the move. The U.S. attack faltered after outdistancing their artillery and food supplies as muddy roads made support difficult.[6] The attack on Metz was not realized as the Germans refortified their positions and the Americans turned their efforts to the Meuse-Argonne offensive. [7]

Prelude

General John Pershing thought that a successful Allied attack in the region of St. Mihiel, Metz, and Verdun would have a significant effect on the German army.[8] General Pershing was also aware that the area's terrain setting dictated that the "clearing" of the rail and road communications into Verdun, and therefore the loss of the German railroad center at Metz would be devastating to the Germans should the Americans capture it. After these goals were accomplished, the Americans could launch offensives into Germany. [9]

Weather Reports

The weather corps of Corps I Operation Order stated: "Visibility: Heavy driving wind and rain during parts of day and night. Roads: Very muddy."[10] This would pose a challenge to the Americans when the order to advance was given. In some parts of the road, the men were almost knee-deep in mud and water. After five days of rain the ground was nearly impassible to both the American tanks and infantry. [11]Many of the tanks wrecked with water leakage into the engine, while others would get stuck in mud flows. Some of the infantry even developed early stages of trench foot, before the trenches were even dug. [12]

German Defensive Positions

Prior to the American operation, the Germans installed many in-depth series of trenches, wire obstacles, and machine-gun nests.[13] The battlefields' terrain included the nearby premises of three villages: Vigneulles, Thiaucourt, and Hannonville-sous-les-Cotes. Their capture would accelerate the envelopment of the German divisions near St. Mihiel. The American forces planned to breach the trenches and then advance along the enemy's logistical road network. [14]

The Germans knew many details about the Allied offensive campaign coming against them. One Swiss newspaper had published the date, time, and duration of the preparatory barrage. However, the German army stationed in the area of St. Mihiel lacked sufficient manpower, firepower, and effective leadership to launch a counter-attack of its own against the Allies.[15] Thus, the Germans decided to pull out of the St. Mihiel salient and consolidate their forces near the Hindenburg Line. The Allied forces discovered the information on a written order to the German Group Armies von Gallwitz. [16]

Although the AEF was new to the French theater of war, they trained hard for several months in preparation of fighting against the German armies. Also, the British use of armor at the Battle of Cambrai[17] impressed General Pershing so much that he ordered the creation of a tank force to support the AEF's infantry. As a result, by September 1918, Colonel George S. Patton Jr. had finished training three tank brigades at Langres, France for an upcoming offensive at the St. Mihiel salient. [18]

Aftermath

General Pershing's operational planning of St. Mihiel separated the salient into several sectors. Each Corps had an assigned sector, by boundaries, that it could operate within. The American V Corps location was at the northwestern vertices, the II French Colonial Corps at the southern apex, and the American IV and I Corps at the south-eastern vertices of the salient.[19] Furthermore, General Pershing's intent was obvious, to envelope the salient by using the main enveloping thrusts of the attack against the weak vertices. The remaining forces would then advance on a broad front toward the direction of Metz. This pincer action by the IV and V Corps was to drive the attack into the salient and to link the friendly forces at the French village of Vigneulles while the II French Colonial Corps kept the remaining Germans tied down. [20]

Explanation of Outcome

One reason for the American forces success at St. Mihiel was General Pershing's thoroughly detailed operations order. General Pershing's operation included detailed plans for penetrating the Germans' trenches using a combined arms approach to warfare. [21]His plan had tanks supporting the advancing infantry, with two tank companies interspersed into a depth of at least three lines, and a third tank company in reserve. The result of the detailed planning was an almost unopposed assault into the salient. The American I Corps reached its first day's objective before noon, and the second days objective by late afternoon of the second. [22]

Another reason for the American success was the audacity of the small unit commanders on the battlefield. Unlike the World War One officers that commanded their soldiers from the rear, Colonel Patton and his subordinates would lead their men from the front lines.[23] They believed that a commander's personal control of the situation would help ease the chaos of the battlefield. [24]

References

- ^ Giese (2004)

- ^ Hanlon (1998)

- ^ History of War (2007)

- ^ Spartacus (2002)

- ^ History of War (2007)

- ^ Giese (2004)

- ^ Spartacus (2002)

- ^ History of War (2007)

- ^ Hanlon (1998)

- ^ Hanlon (1998)

- ^ Giese (2004)

- ^ Spartacus (2002)

- ^ History of War (2007)

- ^ Hanlon (1998)

- ^ Giese (2004)

- ^ Spartacus (2002)

- ^ History of War (2007)

- ^ Hanlon (1998)

- ^ Giese (2004)

- ^ Hanlon (1998)

- ^ History of War (2007)

- ^ Spartacus (2002)

- ^ Giese (2004)

- ^ Hanlon (1998)

- Hanlon, Michael (1998). "St. Mihiel Offensive" (in Egnglish). Retrieved 2008-05-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - "St. Mihiel". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 2008-05-04.

- Giese, Joseph. "Battle Analysis of St. Mihiel". Retrieved 2008-05-04.

- Richard, J. (2007). "Battle of St. Mihiel". History of War. Retrieved 2008-05-04.