Aunt Jemima

Aunt Jemima is a trademark for pancake flour, syrup, and other breakfast foods currently owned by the Quaker Oats Company. The trademark dates to 1893, although Aunt Jemima pancake mix debuted in 1889. The phrase "Aunt Jemima" is sometimes used as a female version of "Uncle Tom" to refer to a black woman who is perceived as obsequiously servile or acting in, or protective of, the interests of whites.[1]

The 1950s television show Beulah came under fire for depicting a "mammy"-like black maid and cook who was somewhat reminiscent of Aunt Jemima. Today, "Beulah" and "Aunt Jemima" are regarded as more or less interchangeable as terms of disparagement.[citation needed] The name "Jemima" is biblical in nature and is the King James Version's rendering of the feminine Hebrew name יְמִימָה (Yəmīmā), the first of Job's daughters born to him at the end of his namesake book of the Bible.

An alternative theory might suggest[citation needed] that the name is related to the name Yemenya, the Santeria Orisha who is the Goddess of the Sea and of female sexuality.

History

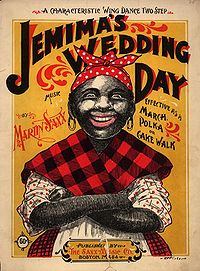

The direct inspiration for Aunt Jemima originates from a minstrelsy/vaudeville song of the same name. Chris L. Rutt of the Pearl Milling Company saw the song being sung by blackface performers Baker & Farrell wearing an apron and kerchief, and appropriated the character.[2]

She is depicted as a plump, smiling, bright-eyed, African-American woman, originally wearing a kerchief over her hair. She was represented as a slave and was the most commonplace representation of the stereotypical "mammy" character.

The character of Aunt Jemima also appeared in vaudeville, played by comedienne-singer Tess Gardella (a white actress, who performed the role in blackface).[3]

Nancy Green, born a slave in Montgomery County, Kentucky, was hired by R.T. Davis Milling Company to play the Jemima character from 1890 to her death on September 24, 1923. As Jemima, Green operated a pancake-cooking display at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois during 1893, beside the "world's largest flour barrel." Harriette Widmer also portrayed the character on radio, in addition to Ethel Ernistine Harper, whose image served as the basis for most remaining Aunt Jemima print advertising starting in the 1950s, until the Jemima character was changed into a composite in the 1960s.

The Aunt Jemima trademark has been modified several times over the years. In her most recent make-over in the late 80s/early 90's, as she reached her 100th anniversary she was transformed into a younger, thinner woman, dressed up, and her kerchief removed to reveal a natural hairdo and pearl earrings. This new look remains with the products to this day.

The Quaker Oats Company bought the brand in 1926.[4] Aunt Jemima frozen foods were licensed out to Aurora Foods in 1996 which in 2004 was absorbed into Pinnacle Foods Corporation.

The character received the Key to the City of Albion, Michigan on January 25, 1964. An actress portraying Jemima visited Albion many times for fundraisers.[5]

Living persons as a basis

- Nancy Green (1834–1923) The first Aunt Jemima, Nancy Green, was born a slave in 1834. She signed an exclusive contract which gave her the right to portray the character for the rest of her life.[6]

- Anna Robinson ( ? –1951) In 1933, Anna Robinson became the second Aunt Jemima, and was featured at the Chicago Century of Progress Exhibition. Robinson's likeness was captured on a painted portrait, an image that changed the product's packaging.[6]

- Edith Wilson (1896 –1981) Prior to becoming the character, Edith Wilson was a blues singer and actress in Chicago. She appeared on Amos 'n' Andy and the movie To Have and Have Not. Quaker Oats had Wilson portray Aunt Jemima on radio, television, and in personal appearances from 1948 to 1966 and she was the first Aunt Jemima to appear in television commercials.[6]

- Ethel Ernestine Harper (1903 - 1979)[1] Ethel Ernestine Harper was Aunt Jemima during the 1950s. She was also the final "living person" basis for the Aunt Jemima image on television until it was changed to an advertising composite logo in the 1960s.[7] She worked as a traveling "Aunt Jemima" on behalf of the Quaker company, giving presentations at schools, churches and other organizations. Prior to assuming the role, Harper graduated from college at the age of 17 and had become a teacher.[6]

- Rosie Hall (1900–1967) Rosie Hall worked for Quaker Oats in the company's advertising department until she discovered their need for a new Aunt Jemima. In 1988 they declared her grave a historical landmark.[6]

- Aylene Lewis ( ? –1964) Aylene Lewis first portrayed Aunt Jemima in 1955 at a restaurant of the same name at Disneyland. As Aunt Jemima, Lewis posed for pictures with visitors along with her co-star, Ruggles the dog. Ruggles appeared extensively alongside Lewis during throughout a large-scale marketing campaign throughout the 1950s.[6]

- Ann Short Harrington (1900-1955)[6]

See also

Notes

- ^ Green, Jonathon. The Cassell DictionarySlag, 1998. p. 36.

- ^ Moss Kendrix: The Advertiser's Holy Trinity: Aunt Jemima, Rastus, and Uncle Ben

- ^ Slide, Anthony. The Encyclopedia of Vaudeville. Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood Press, 1994. p. 15–6.

- ^ Aunt Jemima—Our History

- ^ The Key To The City

- ^ a b c d e f g Moss Kendrix: The Advertiser's Holy Trinity: Aunt Jemima, Rastus, and Uncle Ben

- ^ The Myth of Aunt Jemima: Representations of Race and Region

Further reading

- Goings, Kenneth. Mammy and Uncle Mose: Black Collectibles and American Stereotyping. 1994. Bloomington: Indiana University Press ISBN 0-253-32592-7

- Manning, M.M. Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima. 1998. Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press ISBN 0-8139-1811-1