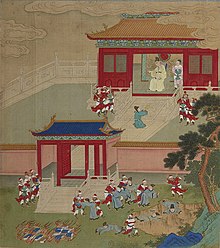

The burning of books and the burying of scholars alive

The burning of books and the burying of scholars alive ( Chinese 焚書坑儒 / 焚书坑儒 , Pinyin fénshū kēngrú ), in traditional Chinese historiography, were large-scale measures of the First Emperor of China, Qin Shihuangdi (r. 259 BC. –210 BC) against classics of the literature of Confucianism and other currents of thought and against Confucian a. a. Scholars. In 213 BC Traditional books such as the Book of Songs (Shijing) and the Book of Documents (Shujing) were confiscated and burned. According to traditional interpretation, 460 scholars were buried alive in the following year (212 BC) . The most important evidence for this event is its mention in the historical records (Shiji) of Sima Qian (approx. 145 BC - 90 BC) and. a. However, some Western and Chinese historians doubt the credibility of this event. They believe that Sima Qian purposely cites the example of Qin Shihuangdi's barbaric politics in order to cast him in a bad light. The other reason for doubt is that Sima Qian's text was not understood correctly and the meaning of his words was distorted. According to the followers of the traditional interpretation, other ancient Chinese scholars mention that the measures had a great impact on Chinese history and society at the time. Although Confucianism suffered a severe blow from the burning of books and the burying of scholars alive, it was rehabilitated after the death of Qin Shihuangdi and the later establishment of the Han Empire (206 BC – 220 AD) .

The traditional interpretation

Book burning

In the years 361–338 BC At the end of the East Zhou period (770–256 BC), six large states formed a union. Qin State was not accepted into this union. Because of this, the Qin ruler Xiaogong initiated a policy of self- empowerment , and the philosopher and politician Shang Yang (390–338 BC) was invited to reform the state. Shang Yang belonged to the legislature and carried out his reforms according to the methods of the legislature . The core of the law was the sovereignty of the law and the need for punitive measures. His reforms had long-term positive effects for Qin, which became the strongest state towards the end of the East Zhou period and was able to conquer its neighboring states. Shang Yang's policies focused on agriculture, strengthening the military, strictly obeying the law, and preventing Confucian classical ideas. Shang Yang was convinced that a state in which the law is the state ideology, no other ideologies, such as B. Confucianism. After Qin Shihuangdi had gained power, he united the states of the Zhou period into a new, unified and strong empire. His Prime Minister Li Si (280 BC – 208 BC), like Shang Yang, was also a supporter of Legism. Sima Qian writes in his Historical Record that the book burning was the idea of Prime Minister Li Si.

Original text:

古 者 天下 散亂 , 莫 之 能 一 , 是以 諸侯 并 作 , 語 皆 道 古 以 害 今 , 飾 虛 言 以 亂 亂 實 , 人 人 善 其所 私 學 , 以 非 上 之 所 建立。 今 皇帝 并 有天下 , 別 黑白 而 定 一 尊。 私 學 而 相與 非法 教 , 人 聞 令 下 , 則 各 以其 學 學 議 之 , 入 則 心 非 非 , 出 則 巷議 , 夸 主 以為 名 , 異 取 以為 高 , 率群 下 以 造 謗。 如此 弗 禁 , 則 主 勢 降 乎 上 , 黨 與 成 乎 下。 禁 之 便。 臣 臣 請 史官 非 秦 記 皆 燒 之。 非 博士 官 所 職 , 天下 敢 、 書 詩 詩 詩、 百家 語 者 , 悉 詣 守 、 尉 雜 燒 之。 有 敢 偶 語 詩書 者 棄 市。 以 古 非 今 者 者 族。 吏 見 知 不 舉 者 與 同 罪。 令 下 三十 日 不 為 , 黥 黥 黥 黥 黥城旦。 所 不去 者 , 醫藥 卜筮 種樹 之 書。 若欲 有 學者 , 以 吏 為 師。

Translation:

In ancient times the empire was divided and in turmoil. There was no one who could unite it. Therefore, several kings appeared at the same time. At that time, scholars praised ancient times to the detriment of the present. They created beautiful lies to the detriment of the truth. They only valued their own doctrine and denied what was created by the rulers of the time. Now you, the emperor, have united everything under heaven, separated the black from the white and created a unified doctrine that is respected by the population. However, supporters of private teaching support each other and speak out against the new legislation. Each new law is immediately discussed by them on the basis of their own teaching. When they enter the palace they condemn everything and after leaving they start arguing again in the streets. Criticism of the ruler is seen among them as heroism. Using other teachings is considered merit. They gather low people around them and sow hatred against the ruler in them. If this is not forbidden, the position of the ruler will be weakened and new parties and groups will form under him. Therefore all of this should be forbidden. I suggest that the official chroniclers burn all records except the Qin annals. Everyone under heaven, with the exception of the scholars at court, who keep the Shijing , the Shujing and essays by philosophers of the Hundred Schools with them, must go to the governor or the commander-in-chief of the army to throw the books in a heap and to burn. Anyone who dares to talk about Shijing or Shujing afterwards must be publicly executed. Anyone who uses the past to slander the present will be executed along with their kin. Officials who take note of this but do not report it must also be executed. Those who did not burn the books in thirty days after the law was enacted should be branded and sentenced to forced labor building castle walls. Books on medicine, agriculture, and divination should not be burned. Those willing to study the laws of Qin should use officials as teachers.

[Interpretation:] The measures that Li Si introduced are evidence of dictatorial censorship and government pressure in the Qin period. Li Si saw the problems of the previous regime in the division of the state. He also saw enlightenment and the free interpretation of Confucian books such as Shi and Shu as a threat to the state. The Prime Minister believed that the fundamental factor in a strong state government was the unity of the state through the law. The alignment of people's thoughts should primarily be accomplished through the alignment of written sources. The ruler enforced this by law. The politics of this regime resulted in many people being severely punished and always living in fear of punishment. Li Si had only ordered the destruction of basic philosophical books, but not the books belonging to other important disciplines such as medicine, agriculture or divination. Notwithstanding this, special civil servants (boshiguan) had access to these books with the permission of the state. The prime minister tried not only to erase memories of certain times before, but also to refrain from any historical record of other government practices that could have been used by Qin subjects to criticize the state.

Burial of the Scholars

Qin Shihuangdi had a dream of getting the elixir of immortality. 215 BC He sent a group of scholars east to the sacred islands where the immortals were to live. However, they did not find anything during their trip, so they sent false messages to Qin Shihuangdi. 212 BC Individual scholars came back to the capital. Because the scholars returned empty-handed, some of them were afraid of being executed and went into hiding. Qin Shihuangdi was very upset about this. Sima Qian writes:

Original text:

始皇 聞 亡 , 乃 大怒 曰 : 「吾 前 收 天下 書 不中用 者 盡 去 之。 悉召 文學 方 術士 甚 眾 眾 , 欲以 興 太平 , 方士 方士 欲 練 以求 奇 藥。 今 聞 韓 眾 去不 報 , 徐 巿 等 費 以 巨 萬 計 , 終 不得 藥 , 徒 姦 利 相告 日 聞。 盧 生 生 等 吾 尊 賜 之 甚 厚 厚 , 今乃 誹謗 我 , 以 重 吾 不 德 也。 諸 者 , 在 咸陽使人 廉 問 , 或 為 訞 言 以 亂 黔首。 」於是 使 御史 悉 案 問 諸 生 , 諸 生 傳 傳 相告 引 , 乃 自 除 犯禁 犯禁 者 四百 六十 餘 人 , 皆 阬 之 咸陽 , 使 天下知 之 , 以 懲 後。 益發 謫 徙 邊。

Translation:

When Qin Shihuangdi heard of the scholars' flight, he became very angry and said, "I used to collect all the books from under the sky and discard all the unnecessary ones. I have gathered many scholars and adepts (wenxue fangshushi) to help create the Great Peace. The adepts promised me the elixir of immortality. I recently learned that Han Zhong fled before he could produce anything, that Xu Shi and others wasted huge sums of money but found nothing, but reported successes in their base, selfish interests every day. I have richly rewarded Lu Shen and others, but now they scorn me and accuse me of lack of virtue. As for the scholars in Xianyang, I sent people to investigate to see which of them were spreading bad things behind my back, to sow dissension among the common people. ”Qin Shihuangdi sent imperial historians to meet all scholars (zhusheng ) to question. The scholars began to hang on to one another to prove their own innocence. 460 scholars were charged with breaking the law and were all executed in Xianyang. The emperor set an example so that everyone under Heaven would be informed. An even greater number of scholars were sent to the frontier.

[Interpretation:] According to the traditional interpretation, Qin Shihuangdi was afraid of clandestine attacks. After being lied to, he began to be suspicious of Confucian scholars and viewed Confucians as a threat to national security. So he ordered the scholars who opposed the regime to be found and executed. In addition to the above quotation, there are three other mentions in Shiji that deal with the burial of scholars.

The barbaric execution of the scholars had fatal effects on Confucianism. As a result of this, and the continued persecution of the Confucians, who formed the social elite of the time, the Qin Empire lost educated and worthy representatives of society. Many of the scholars have been forced to live in hiding for fear of persecution and punishment.

Other interpretations

Some Chinese and Western sinologists and historians have questioned the credibility of the brutal measures allegedly carried out by Qin Shihuangdi. Michael Nylan writes that the book burning did not take such radical forms or never happened. She believes that several Confucian scholars at the Qin Shihuangdi Imperial Court still focused on and worked on Shi and Shu . The American sinologist believes that Shi , Shu and Yijing were not destroyed at all and that it is unlikely that other classical works were also damaged because they did not contain any anti-Qin content. Martin Kern, another sinologist, is also against the traditional interpretation of the Qin story. It shows that there is no mention of these measures prior to Sima Qian's Shiji . Another mention comes from Wei Hong, the author of the preface to Shujing , who lived in the first century AD. Wei Hong interprets Qin Shihuangdi's policies as anti-Confucian. The firm statement "fenshu kengru" (book burning and burial of scholars) is only seen for the first time in the Shujing version of Kong Anguo in AD 317. The modern Chinese scholar Li Kaiyuan speaks of contradictions in Shiji . At the beginning of the Shiji section, the scholars who were sent in search of the elixir of immortality are called fangshi ( Chinese 方士 , pinyin fāngshì ), while at the end they are called zhusheng (Chinese 諸 生, pinyin zhūshēng ). Li Kaiyuan believes that fangshi were the adepts who followed Daoist philosophy, but the word zhusheng in this case is unclear, it can refer to both adept and a Confucian scholar. The ambiguities in the historical works cast doubt on their credibility.

Re-evaluation of Qin Shihuangdi's social policy

Qin Shihuangdi was the first ruler in Chinese history to unite different Chinese states into one great and strong empire. He also built the first legal system. The law occupied the highest place in society, and all citizens of Qin State were required to obey it, regardless of social or material position. The strict style of government, large construction projects, e.g. For example, the Great Wall of China or the Imperial Palace in the capital led to great social tensions. Some Confucian scholars recommended that Qin Shihuangdi divide the state as in the earlier Zhou period in order to alleviate social tensions. Prime Minister Li Si severely criticized the Confucians on this very point for believing that only a united Qin Empire could remain strong. The position of Confucian scholars against the government led to anti-Confucian policies and measures. The ban on Confucianism affected the entirety of the state ideology of the Qin Empire. In addition, the new state ideology did not correspond to the traditions of the time, which were based on the ideas of Confucius.

literature

- Lois Mai Chan: The Burning of the Books in China, 213 BC In: The Journal of Library History . No. 7 (2), 1972, pp. 101-108.

- Shengxi Chen 陈 生 玺: Qin Shihuang yuanhe fenshu kengru秦始皇 缘何 焚书坑儒. In: Nankai xuebao南开 学报. No. 3, 2011, pp. 123-132.

- Martin Kern: Early Chinese Literature: Beginnings through Western Han . In: Kang-i Sun Chang, Stephen Owen: The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature . Cambridge University Press 2010. pp. 1-14, ISBN 9780521855587

- Kaiyuan Li 李 开元: Fenshu kengru de zhenwei xushi焚书坑儒 的 真伪 虚实. In: Shixue jikan史学 集刊 No. 6, 2010, pp. 36–47.

- Michael Nylan: The five “Confucian” classics. Yale University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-300-08185-5 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Shengxi Chen 陈 生 玺: Qin Shihuang yuanhe fenshu kengru秦始皇 缘何 焚书坑儒. In: Nankai xuebao南开 学报. No. 3, 2011, pp. 123-125.

- ↑ Shengxi Chen 陈 生 玺: Qin Shihuang yuanhe fenshu kengru秦始皇 缘何 焚书坑儒. In: Nankai xuebao南开 学报. No. 3, 2011, p. 125.

- ↑ Shiji史記, Sima Qian 司馬遷 (approx. 145 BC - 90 BC). Zhonghua shuju中華書局, Volume 1, 1985, p. 225.

- ↑ Lois Mai Chan: The Burning of the Books in China, 213 BC In: The Journal of Library History. No. 7 (2), 1972, p. 105.

- ↑ Chen, Shengxi 陈 生 玺: Qin Shihuang yuanhe fenshu kengru秦始皇 缘何 焚书坑儒, In: Nankai xuebao南开 学报. Volume 3, 2011, p. 127.

- ↑ Shiji史記, Sima Qian 司馬遷 (approx. 145 BC - 90 BC). Zhonghua shuju中華書局, Volume 1, 1985, p. 258.

- ↑ Shengxi Chen 陈 生 玺: Qin Shihuang yuanhe fenshu kengru秦始皇 缘何 焚书坑儒. In: Nankai xuebao南开 学报. No. 3, 2011, pp. 128-129.

- ↑ Liang, Zonghua 梁宗华: Qinchao jin ru yundong ji qi shehui houguo秦朝 禁 儒 运动 及其 社会 后果. In: Guanzi xuekan管子 学 刊. Volume 2, 1992, p. 62.

- ↑ Michael Nylan: The five “Confucian” classics , Yale University Press, 2001, p. 29.

- ↑ Martin Kern: Early Chinese literature: Beginnings through Western Han . In: Kang-i Sun Chang, Stephen Owen: The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature , Cambridge University Press, 2010, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Kaiyuan Li 李 开元: Fenshu kengru de zhenwei xushi焚书坑儒 的 真伪 虚实. In: Shixue jikan史学 集刊. No. 6, 2010, p. 39.

- ↑ Ying Li 李映: Lun Qinchao shehui zhong tongzhi jieji de falü tequan论 秦朝 社会 中 统治 阶级 的 法律 特权. In: Guangxi Minzu xueyuan xuebao广西 民族 学院 学报. December, 2005, p. 119.

- ↑ Zonghua Liang 梁宗华: Qinchao jin ru yundong ji qi shehui houguo秦朝 禁 儒 运动 及其 社会 后果. In: Guanzi xuekan管子 学 刊. No. 2, 1992, pp. 55-62.