Categorical judgment

The expression categorical judgment ( Latin : categoria: basic statement) (also: categorical sentence , categorical statement ) is a concept of traditional, Aristotelian logic , especially the syllogistics . In the categorical judgment something (the predicate, P , for example a property) is assigned or denied to a class of objects (the subject, S ) by means of a copula . The categorical judgment is thus an atomic statement , that is, a statement that is not composed of other statements.

An example of a categorical judgment is the statement “All people are mortal”; here the logical subject is the term “human” and the logical predicate the term “mortal”. (The terms “subject” and “predicate” are used in different meanings in traditional logic than in grammar.)

The categorical judgment stands on the one hand in contrast to compound statements (in traditional logic: hypothetical or disjunctive judgments, for example "if A, then B" or "A or B"), on the other hand to the modal statements with modalities such as possibility or necessity .

In the Aristotelian syllogistic - in contrast to modern logic - it is generally made a requirement that expressions for subject and predicate are not empty (example for an empty subject: "unicorns"). This requirement is called existential presupposition.

The four forms of judgment

Traditional logic assumes that each categorical judgment can be assigned to one of the following four types:

- "All S are P" (generally affirmative form of judgment, called A judgment in the tradition)

- "No S is P" (generally negative form of judgment, in the tradition E-judgment)

- "Some S are P" (special affirmative form of judgment, in tradition I judgment)

- "Some S are not P" (special negative form of judgment, in the tradition O-judgment)

Quantity and quality

The property of a statement, how many objects it talks about, is traditionally called the quantity of that statement. In this sense there are two quantities in the syllogism, namely particular and universal. The property of a statement to assign or deny a predicate to a subject is traditionally called the quality of this statement. If a statement assigns a predicate to a subject, it is called an affirmative statement, if it denies it, it is called a negative statement. The types of statements are broken down in the following table according to their quality and quantity:

| general | particular | |

|---|---|---|

| affirmative | A judgment | I judgment |

| negative | E judgment | O judgment |

Examples

- "The fungus is a spore plant" (type 1, A-judgment - quantity: general, quality: affirmative)

- "Whales do not belong to the fish" (type 2, E-judgment - quantity: general, quality: negative)

- "Some mammals are herbivores" (Type 3, I judgment - quantity: particular, quality: affirmative)

- "Most people are not Europeans" (type 4, original judgment - quantity: particular, quality: negative)

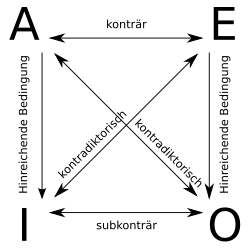

Adversarial, contrarian and subcontractual opposites, sub- and superalternation

Judgments of the four categories are related to each other in specific conditions:

- The judgment pairs 1 and 4 (A and O) and 2 and 3 (E and I) form contradictory opposites, i.e. That is, if one judgment is true, the other is automatically false and vice versa. They can neither be both true together nor both false together. With one of the above examples this means that from the sentence “Most people are not Europeans” the judgment “It is not true that all people are Europeans” can be inferred.

- The relationship between statements that may not be true at the same time, but may be false at the same time, is referred to as a contrary contrast. This is the relationship between types 1 and 2 (A and E). An example: “All Wikipedians are Munich” (type 1) is in contrast to the assertion “No Wikipedians are Munich” (type 2). As can be easily determined empirically, neither of the two statements is correct.

- A contradiction is called subcontracting if both statements cannot be false at the same time, but both can be true. This is the relationship between types 3 and 4 (I and O). The statements "There are regulations of the new spelling that are advantageous" and "There are regulations of the new spelling that are not advantageous" can both be true, but never both false.

- Assuming that the subject is not empty, the truth of a type 1 statement follows the truth of the corresponding type 3 statement. Under the same assumption, the truth of a type 2 statement follows the truth of the corresponding type 4 statement. This corollary relationship is traditionally referred to as a subalternation . An example: From the A-statement "All pigs are pink" follows the I-statement "There are pink pigs".

- Assuming that the subject is not empty, the falseness of a type 3 statement follows from the falseness of the corresponding type 1 statement and from the falsehood of a type 4 statement the falsehood of the corresponding type 2 statement. This inferential relationship is traditionally referred to as the superalternation . An example: Since the I-statement "There are pink pigs" follows from the A-statement "All pigs are pink", the falseness of the I-statement "There are pink pigs" leads to the falseness of the A-statement "All pigs are pink ”.

A is a sufficient condition for I (just like E is for O). I for A and O for E are a necessary condition.

These relationships are illustrated graphically in a diagram that has become known as the logical square (see illustration). The oldest known writing of the logical square comes from the second century AD and is ascribed to Apuleius of Madauros .

Treatment in strict logic

In the following paragraph the treatment of the categorical judgments in the strict logic (by Walther Brüning ) is presented:

He sees the categorical judgments as definite formulas of the second level .

From the assumption of the judgments, statements about the fulfillment of the terms can be derived: The universal judgments claim that all are SP (SaP) or ~ P (SeP). This means that an S does not exist without P (SaP) or without ~ P (SeP). The particular judgments claim that some are SP (SiP) or ~ P (SoP). Values of negative validity ( N , for negation), ( A , for affirmation) and indefinite validity ( u ) can therefore be derived from the judgments . SaP says that there can be no S without P (negative validity), but initially it does not make any statement about whether there are S and P or P without S. SiP, on the other hand, makes a positive statement, namely that there are S that P are (or that S and P appear together), but leaves the question of whether there is also S without P or P without S, indefinite. The graphic opposite illustrates this for all four types of judgment (negative validity is shown in red, positive validity in green).

The following tabular overview of the specifications made by the four types of judgment about S and P results:

| SaP | SeP | SiP | SoP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S, P | u | N | A. | u |

| ~ S, P | u | u | u | u |

| S, ~ P | N | u | u | A. |

| ~ S, ~ P | u | u | u | u |

Brüning then also includes existential conditions in his teaching in order to build up a syllogistic calculation (" A demands ").

He then connects two categorical judgments by means of a third term, the middle term. In doing so, the formulas are " extended " (ie extended by the term, so to speak, which is not involved). Finally, he defines two rules of derivation in order to obtain the syllogisms in a relatively simple way.

The paraphrases of the categorical judgments are also based on Albert Menne's paraphrases .

See also

literature

- Judgment . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 16, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, pp. 17–18.

Web links

- Niko Strobach: Newer interpretations of the Aristotelian syllogistics . (PDF; 114 kB)

- Klaus Glashoff: On the translation of Aristotelian logic into predicate logic . (PDF) 2005