Contraction and convergence

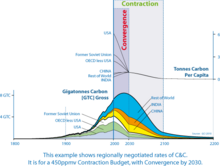

Contraction and convergence , from engl. Contraction and convergence , often translated as reduction and convergence , is a burden-sharing process for climate protection . It consists of two dimensions: Contraction describes the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions overall to a target level that limits global warming . Convergence means that the per capita emissions of different countries should converge and eventually adjust in a target year. In this way, the overall decreasing amount of emissions should be distributed fairly among all people and at the same time ensure feasibility.

Principles

Contraction and convergence is based on a global carbon budget that humanity can at most emit if global warming is to be limited to a certain level with a certain probability. The approach includes the emissions of CO 2 and other greenhouse gases, provided that reliable, country-specific data on their emissions are available. The carbon budget is seen as a finite, global commons that has to be shared internationally. Contraction and Convergence now proposes a framework how annual emissions can be reduced to a sustainable level and how the remaining budget can be distributed among all countries in the world.

contraction

The contraction, i.e. the reduction in the total emissions across all countries, must take place so quickly that the carbon budget is adhered to. A carbon budget is usually assumed here that is in line with the two-degree target recognized at the 2010 UN Climate Change Conference in Cancún . At the end of the contraction phase, when the budget has been used up, a sustainable level of emissions must be achieved. With a world population of around 7 billion people (2011), the sustainable emission level is around 1–2 tons of CO 2 per capita. If the world population grows - up to 10 billion people are predicted in the year 2100 - then the sustainable level of emissions must be distributed among more people. I.e. Even after the end of the contraction phase , the per capita CO 2 emissions may have to decrease further.

convergence

The convergence idea is based on the assumption that every human being should be granted the same amount of carbon dioxide emissions. This equity goal (see climate justice ) is to be achieved at the end of the convergence phase. At the same time, however, convergence should not overburden individual countries either, so that sufficient alternative energy sources can be developed and energy efficiency measures implemented. For this reason, countries initially receive a number of emission rights that are based on their gross national product (GNP) or the annual emissions caused up to that point. This allocation, which is initially proportional to the BNP, is then increasingly approximated over the convergence period to one that is proportional to the population. While states whose emissions are above the convergence level have to significantly reduce their emissions in this phase, some developing countries with emissions that are far below average can initially increase their emissions. So to development objectives be taken into account. Since the proposal was developed in the 1990s, however, such a large proportion of the carbon budget for the two-degree target has now been used that most of the emerging countries should also have to reduce their emissions very soon.

Other features and options

The concept does not include historical emissions as additional reduction obligations. On the contrary, high historical emissions in the years prior to the establishment of a procedure based on the principles of contraction and convergence can even result in an even higher initial allocation of emission rights. When convergence was reached, the industrialized countries would have historically emitted a multiple of greenhouse gases per capita than developing countries. According to a model calculation by Gignac and Matthews (2015), with a convergence from 2013 to 2050, an end of the contraction in 2070 and a CO 2 budget of 1000 Gt compatible with the two-degree target , this remaining budget would also be almost 90% will be consumed mainly by the industrialized countries before convergence is reached. Only a small part would be divided according to the per capita criterion. For this reason, the economist Nicholas Stern called the concept at the 2007 UN climate conference in Bali a “spectacularly weak form of justice”.

The GCI proposes compensation payments to compensate for unequal historical emissions. Gignac and Matthews (2015) calculated the emission credits and debts that had accrued from 1990 onwards compared to the per capita criterion. Full monetary compensation of the debt would require high compensation payments. If the US Environmental Protection Agency estimates the social carbon costs of US $ 11 to US $ 100 per tonne of CO 2 , the compensation amount for the US would be US $ 1,550 billion (similar to the costs of the " war on terror ") 2001–2014) to 15,000 billion US $ (roughly the gross domestic product of the USA in 2010).

It is sometimes suggested that states should be able to sell and buy allotments of emission rights through emissions trading . In this way, the emission reductions can take place where they cause the lowest costs. Non-state emissions from international air and sea traffic can then also be included in such an emissions trading scheme .

Contraction and convergence is an accurate method because the global emissions budget and the global emissions path are specified. It can be designed continuously , i.e. leaps in the allocation of emission rights and the associated threats to economic stability can be avoided. The shape or the temporal course of the convergence and contraction paths can be agreed differently, for example linearly or based on estimated minimum total costs.

With the world's population increasing, per capita emissions have to fall in order to meet the budget. The size of the population of the countries involved in the allocation of emission rights can be continually re-taken into account or determined on the basis of a reference year. By aiming at the same per capita emissions, the procedure does not take into account the possibly different needs of different countries, which could be justified, for example, by the geographical or climatic situation. An equal per capita quota does not take into account the division of labor in the world economy. Some countries have particularly high emissions because they produce a particularly large number of particularly emission-intensive goods for export; the same per capita emissions can cause existential difficulties in individual cases. Undisclosed greenhouse gases, land use changes and other factors that also contribute to global warming need to be considered outside the framework of contraction and convergence.

The process is said to be simple and transparent.

Development and significance for climate policy

The concept was developed in 1990 by the Global Commons Institute over a period of three years. In 2007, it was discussed by a broad public for the first time in German-speaking countries under the name Carbon Justice .

The concept was supported by a number of political and scientific actors. The German Advisory Council on Global Change recommended the concept for the second commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol, starting in 2012, and proposed 2050 as the year of convergence. Contraction and convergence were considered to be one of the most popular models for a climate protection regime in the second commitment period. Many models have taken up the approach and developed it further, for example the dynamic convergence model of the Federal Environment Agency from 2005.

Application outside of climate policy

In the meantime, the scope of the concept has been expanded: not only greenhouse gas emissions are to be reduced and standardized worldwide, but also the entire natural consumption of humans. This suggestion is formulated in the Fair Future study published by the Wuppertal Institute . The WWF developed the Living Planet Report for the entire ecological footprint of humanity a similar model for the future, that to avoid confusion, the name S & S ( Shrink and Share received).

Comparison with other burden sharing schemes

An alternative concept that includes historical emissions (responsibility) and current capacities (capacities) of the states in a multi-indicator model is the Greenhouse Development Rights (GDRs) model of the Eco-Equity institute , funded by Heinrich-Böll- Foundation , and ChristianAid . In a comparison published by the Böll Foundation in the run-up to the UN Climate Change Conference in Copenhagen in 2009 , the ethicists Kraus and Ott attribute better political acceptability, easier implementation and a more secure ethical basis to the concept of contraction and convergence. The science author Santarius emphasizes that contraction and convergence do not take into account the historical responsibility of industrialized countries and that developing countries can hardly agree to the concept because it would soon oblige them to reduce emissions. He also sees sufficient political support for GDRs as problematic.

literature

Application in climate protection :

- Aubrey Meyer: The Kyoto Protocol and the Emergence of "Contraction and Convergence" as a Framework for an International Political Solution to Greenhouse Gas Abatement . In: Olav Hohmeyer and Klaus Rennings, Center for European Economic Research (Eds.): Man-Made Climate Change - Economic Aspects and Policy Options, ZEW Economic Studies . tape 1 , 1999, ISBN 978-3-7908-1146-9 , pp. 324 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-642-47035-6_15 .

- Reduction and Contraction (Call of the Global Commons Institute , German translation; Reduction and Contraction (PDF; 262 kB)).

Other uses :

- Károly Henrich: Contraction & Convergence: Problems of the sustainability-economic generalization of a future model of climate policy. University of Kassel 2006, Economic Discussion Papers 83/06 uni-kassel.de (PDF; 433 kB).

- Károly Henrich: Contraction and convergence as key concepts of the political economy of the environment. Metropolis Verlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-89518-604-2

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alina Averchenkova, Nicholas Stern and Dimitri Zenghelis: Taming the beasts of 'burden-sharing': an analysis of equitable mitigation actions and approaches to 2030 mitigation pledges . Policy paper. Ed .: Center for Climate Change Economics and Policy, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment. December 2014, p. 11 .

- ↑ a b c Renaud Gignac and H Damon Matthews: Allocation a 2 ° C cumulative carbon budget to countries . In: Environmental Research Letters . July 2015, doi : 10.1088 / 1748-9326 / 10/7/075004 .

- ↑ Quoted in: Jörg Haas: … a spectacularly weak form of justice. In: Climate of Justice. December 11, 2007, accessed September 11, 2015 .

- ^ Aubrey Meyer: The Kyoto Protocol and the Emergence of "Contraction and Convergence" as a Framework for an International Political Solution to Greenhouse Gas Abatement . 1999, p. 324 .

- ^ Amy Belasco: The Cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Global War on Terror Operations Since 9/11 . Ed .: Congressional Research Service. December 8, 2014 ( fas.org [PDF]).

- ^ Aubrey Meyer: The Kyoto Protocol and the Emergence of "Contraction and Convergence" as a Framework for an International Political Solution to Greenhouse Gas Abatement . 1999, p. 312,321-322 .

- ↑ Michael R. Raupach: Sharing a quota on cumulative carbon emissions . In: Nature Climate Change . 2014, p. 876 , doi : 10.1038 / nclimate2384 .

- ↑ a b c Hartmut Graßl u. a .: Thinking beyond Kyoto - climate protection strategies for the 21st century . Special report. Ed .: Scientific Advisory Board of the Federal Government on Global Change. 2003, ISBN 3-936191-03-4 , pp. 25-28.65 .

- ↑ a b Scientific Services of the German Bundestag (Ed.): Definition, discussion and significance of various climate targets - per capita reduction targets, relative reduction targets and economically-linked reduction targets . WD 8 - 105/07, 2007 ( bundestag.de [PDF]).

- ^ Aubrey Meyer: The Kyoto Protocol and the Emergence of "Contraction and Convergence" as a Framework for an International Political Solution to Greenhouse Gas Abatement . 1999, p. 302 .

- ↑ Hartmut Graßl u. a .: Thinking beyond Kyoto - climate protection strategies for the 21st century . Special report. Ed .: Scientific Advisory Board of the Federal Government on Global Change. 2003, ISBN 3-936191-03-4 , pp. 65 .

- ^ Wuppertal Institute (ed.): Fair Future . CH Beck, 2005, ISBN 3-406-52788-4 , 5.1 contraction and convergence.

- ↑ WWF (Ed.): Living Planet Report 2006 . Gland, Switzerland ( assets.panda.org [PDF; 4.6 MB ]).

- ^ Greenhouse Development Right. Eco-Equity, accessed September 11, 2015 .

- ^ Katrin Kraus, Konrad Ott and Tilman Santarius: How Fair is Fair Enough? Two climate concepts compared . In: Böll topic . No. 2 , 2009 ( boell.de [PDF]).

Web links

- Keyword “reduction and convergence” from the WBGU special report Thinking beyond Kyoto - climate protection strategies for the 21st century. from 2003