Lillibullero

Lillibullero is the most common title of probably in the early 17th century in Ireland incurred folk song . The characteristic 6 / 8 - cycle suggests this is that it was originally a Jig has acted. As such, the piece is still interpreted by folk musicians today . But there is also the assumption that Lillibullero was initially a lullaby , which is underpinned by the fact that a variant of the melody has developed into the rock-a-bye baby, which is extremely popular to this day (mainly in the USA ) . Outside of the British Isles , Lillibullero's notoriety is largely due to the fact that the song has been used as a theme song by the BBC World Service since the second half of the 20th century. Numerous variants are used for the spelling of the title, including Lilliburlero , Lily Bolero and many others.

The song is listed in the Roud Folk Song Index under number 3038.

Early transmission of the melody

It is assumed that the melody was already known in England at the time of the Civil War , i.e. shortly before the middle of the 17th century. The origin in Ireland is based on this assumption for the time around 1620. The first reliable transmission of the melody can be found in the anonymous collection An Antidote Against Melancholy , published in London in 1661 ; the text of the song begins here with the words "There was an old man of Waltham Cross". The contemporaries seem to have been aware of the originally Irish origin of the sage. This can be seen, among other things, from the title that the composer Henry Purcell chose when he published the melody in 1689 as A New Irish Tune in G in Musick's Hand-Maid , a collection of his own compositions for harpsichord . The baroque music was the modern idea of melodic invention as "intellectual property" of a particular composer still largely unfamiliar, so it would be ahistorical, Purcell of plagiarism to accuse. The same applies to the Marche du Prince d'Orange , which is listed in a handwritten version (signature Ms. Mus. Sch. F576, 9-12) in the Bodleian Library of Oxford University as a composition by Jean-Baptiste Lully (LWV 75/18) becomes. The manuscript in the Bodleiana also mentions the alternative title Lairi bollairy / bolli nola , which indicates that the apparent nonsense syllables, which still make up a considerable part of the best-known text variants, were sung back then. The same march is also attributed to Lully's competitor as the court composer of Louis XIV , namely André Philidor . In both cases, however, it is not possible to date the time of origin more precisely than to the last decades of the 17th century, so that from the French versions it cannot be concluded with certainty whether the Lillibullero syllables were already independent of the later so known political satirical text were in use.

Political satire

The English text from around 1690

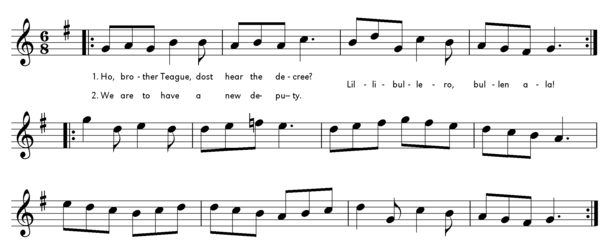

The melody has been linked to a number of different texts over the course of over three centuries. Most of them are humorous, and many comment on daily events in a satirical way. The mocking verses that their political opponents put into the mouths of the Irish Catholic supporters of the English King James II were particularly widespread :

“Ho, brother Teague, dost hear the decree? We are to have a new deputy.

Oh, by my soul, it is a Talbot, and he will cut every Englishman's throat.

Now Tyrconnell is come ashore, and we shall have commissions galore,

and everyone that won't go to Mass, he will be turned out to look like an ass.

Now the heretics all go down, by Christ and St Patrick the nation's our own.

There was an old prophecy found in a bog: the country'd be ruled by an ass and a dog.

Now this prophecy is all come to pass, for James is the dog and Tyrconnell's the ass. "

“Heda, Brother Teague, have you heard of the decree? We're supposed to have a new Lord Deputy.

By my soul, it's a Talbot, and it will cut the throat of any Englishman.

Now Tyrconnell has landed, and we will have appointments galore,

and anyone who does not attend Mass will look like a donkey.

Now the heretics are perishing, and with the help of Christ and St. Patrick the land will be ours again.

An old prophecy was found in the moor, according to which the country would one day be ruled by a donkey and a dog.

This prophecy has now been fulfilled, for Jacob is the dog and Tyrconnell the donkey. "

Here the political goals of the Jacobites are summarized in a polemically simplified and exaggerated way. Only from the last line does it become clear that the text actually represents the position of the opposing side (namely the largely Protestant settlers of English and Scottish origin). The latter supported the Glorious Revolution and thus the aspirant to the throne favored by the English parliament , Jacob's nephew and son-in-law Wilhelm of Orange, from 1689 as Wilhelm III. King of England.

The anonymous author (s) of the lines quoted above assume, as is not unusual for a satirical commentary on daily politics, an intimate knowledge of the caricatured events, people and views as well as everyday language usage.

- Teague [teɪɡ] (also taig , TEG and other spellings), a corruption of the male Irish first name Tadhg [taɪɡ] , is in use today to insult for nationalistisch minded and Catholic Irish.

- Richard Talbot, 1st Earl of Tyrconnell , was the candidate of Jacob II for the post of Lord Deputy , the supreme representative of the Crown in Ireland. When Talbot took office in 1685, he was the first Irish Catholic to hold this position in nearly two hundred years.

- The "appointments" mentioned in the text allude to Talbot's policy of giving offices and posts (especially in the army) preferentially to Catholics.

- The allusion to impending violent attacks against the English population ("cut every Englishman's throat") reflects memories of the riots during the Irish Rebellion of 1641 .

- The invocation of Christ and the Irish national saint St. Patrick in connection with very secular questions caricatures a practice common in Ireland until the recent past.

- Likewise, the closing lines mock the belief in prophecy that is widespread in Irish popular piety . The equation of the governor with a dog was also obvious to the contemporaries insofar as the Talbot Hound was also the name of a breed of hunting dog popular in the British aristocracy .

The syllable chant

Much of the melody, including the particularly catchy chorus , is sung on syllables that make no sense in English. Nevertheless, the apparently nonsensical sequence of sounds Lillibullero has even become the generally accepted title of the song. The practice of singing on nonsense syllables is part of the common repertoire of most folk song traditions in Europe, and it can also be found in most of the other musical cultures of the world. Often these are actually just rhythmic fillings ("trallala"), but not infrequently such syllable sequences can also be an indication of the adoption of foreign-language text fragments. In the case of Lillibullero, it seems reasonable to attempt to interpret the corresponding passages as corrupted Irish sentence fragments, and in fact there are numerous speculations about this:

- The refrain is interpreted as the Irish sentence lile ba léir é, ba linn an lá , which means something like "'Lilly' was clear / bright and the day was ours". Who or what “Lilly” is about, however, requires a further explanation. A reference to the fleur de lis (the lily , English lily , as heraldic symbol of French royalty) and thus an allusion to France as an ally of the Stuart kings and the Irish Catholics is assumed.

- As early as the 16th century, a certain William Lilly had proclaimed or interpreted prophecies that foretold a Catholic king on the English throne. In this sense, the Irish sentence above could be understood as: "Lilly said it clearly, our day will come."

- Lilli is a pet form of the first name William, and bullero can be deciphered as the Irish buaill léir ó , which then means: "William (of Orange) conquered all who were left".

Whether the nonsense syllables are originally Irish words and whether they are actually in the described, relatively close connection with the meaning of the English text, has not yet been clarified beyond these rather speculative approaches. However, it is precisely this ultimately meaningless part of the text that has been adopted in many new versions, essentially unchanged.

Rock-a-bye baby

A variant of the melody evolved into Rock-a-bye baby, a song that was mainly popular in the United States .

literature

- James Porter: The cultural expropriation of Lillibulero. In: Scottish Studies Review 5: 1, 2004.

Web links

- BBC website featuring a vocal version of Lillibullero

- The arrangement by David Arnold, as it can be heard as the signature tune of the BBC World Service (WAV file; 232 kB)

- Midi version of A New Irish Tune in G (Lilliburlero) , Z 646, based on Henry Purcell's Musick's Hand-Maid (Pieces for Harpsichord) from 1689

- Interpretation of Purcell's A New Irish Tune , harpsichord: Gustav Leonhardt

- Brief outline of the story of Lillibullero as the theme tune of the BBC World Service