Munsterberg deception

The Münsterberg illusion is a visual perception illusion in which two parallel vertical rows of black squares on a light background are perceived as inclined compared to the perpendicular when they are shifted against each other and the squares are connected by vertical lines. It is named after its discoverer Hugo Münsterberg .

history

The deception was published in 1897 by Hugo Munsterberg, in which he reported that he had found it "not through theoretical considerations, but by looking at an American horse-drawn train ticket". He also constructed a mechanical device on which the deception could be varied experimentally. Pierce examined the influence of the irradiation effect . Fraser coined the term “unit of direction” for two black squares connected by a line to the left and right of the figure axis (Fig. 3). A geometrical unit defined in this way has C2 symmetry. Several variants of the stimulus have been published and extensively studied by Kitaoka, Pinna, and Brelstaff.

The stimulus

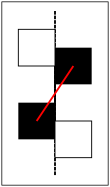

Two black squares adjoin each other, but are shifted by half a side length. The vertical distances between the black squares correspond to their side length, so that the light areas in between are also perceived as squares. Lines run along the figure axis, each connecting two black squares on opposite sides of the axis, but at the same time separating the white squares.

observation

The black lines between one square and the next suggest a line running continuously between the two rows of squares. This appears to be inclined clockwise to the vertical and the entire figure appears to be tilted. Accordingly, the sides of the squares adjoining the center line no longer appear to be exactly parallel to their outer sides. The illusion is best perceived by looking at the entire stimulus and looking at a spot slightly to the side of the figure. The intensity of the illusion is reduced if you only focus on a small section. Rotating it through any angle does not change the impression significantly. The illusion disappears if the black connecting lines are missing or if only one of the two vertical rows of black squares is moved a little sideways from the center line. The effect can be seen in the same intensity on the figure in white on a black background.

Difference to the Café Wall Illusion

In the Münsterberg illusion, only two rows of pure black squares on a light background, with a black line running between them, can be seen, while the Café Wall Illusion consists of several rows of rectangles separated by gray lines. It is also sometimes referred to as the more general form of the Munsterberg illusion.

Interpretations

- According to Münsterberg, the illusion arises from irradiation . After that, a light square in a black area appears larger than the other way around. To explain this, one takes a section in Fig. 1 (Fig. 2) in which two light areas perceived as squares are separated from each other by the black line. The left, slightly higher square (A) is bordered by two sides with black surfaces at the top right. According to the author, there it is perceived as enlarged due to the irradiation effect: "The main effect of the irradiation is apparently that the white square not only pushes its right-angled shape beyond the center line, but apparently drills into the black double square at an acute angle." A little deeper, the right white square (B) does the same in the direction to the bottom left and therefore the black-white border is perceived as tilted clockwise. The line remains unchanged, however, where white areas can be seen on both sides. The repeating effect on each section adds up to a slope of the entire figure.

- Kitaoka complements this interpretation by postulating the same effect for the black squares and extending it to non-right angles. Kitaoka, Pinna and Brelstaff explain the direction of the perceived inclination with the mechanism of "contrast polarities".

- Influence of virtual lines. According to this, perception has a tendency to connect areas of the same perceived brightness with one another using virtual lines. Examples are the Kanizsa triangle or the Café Wall Illusion. Kitaoka, Pinna and Brelstaff (2004) already discussed a possible effect of spatial filtering in the course of the perception process. As suggested by Fraser (1908), the Münsterberg figure is mentally broken down into individual repetitive sections (Fig. 3). These have C2 symmetry and indicate a direction at an angle to the figure axis. Perception replaces the geometric unit with a virtual line, which is inclined in the direction of the shortest connection between the optical centers of gravity of the squares (red line in Figure 3). This interacts with the real line that connects the squares via their corners on the inside. This then also appears tilted. All in all, this leads to an apparent clockwise rotation of the whole figure.

variants

The basic shape, observed from Münsterberg on displaced squares, can be changed in many ways without the illusion disappearing. One of these variants - with both black and white connecting lines - consists of rounded elements (Fig. 4).

Comparable deceptions

- A similar effect can also be seen in the “twisted cord” by Fraser (1908).

- Gregory and Heard published the Café Wall Illusion . The squares are replaced by rectangles, alternating in black and white, arranged in several horizontal rows. As with the Münsterberg illusion, the dividing line between the rows is felt to be inclined against their geometric course, but the apparent trapezoidal shape of the individual elements is also more prominent. The Café Wall illusion is sometimes referred to as the general form of the Münsterberg illusion.

- In the Zöllner deception, too, lines are apparently inclined compared to their actual course.

- Wade (1982) as well as Kitaoka (1998) bring two-dimensional examples in which straight lines appear curved or parallel lines appear inclined to one another.

Individual evidence

- ^ H. Münsterberg: The displaced chessboard figure. In: Journal of Psychology. 5, 1897, pp. 185-188.

- ↑ AH Pierce: The illusion of the kindergarten patterns. In: Psychological Review. 5, 1898, pp. 233-253.

- ^ J. Fraser: A New Visual Illusion of Direction. In: British Journal of Psychology. 2, 1908, pp. 307-320.

- ^ A. Kitaoka, B. Pinna, G. Brelstaff: Last but not least. In: Perception. 30, 2001, pp. 637-646.

- ^ A. Kitaoka: Apparent contraction of edge angles. In: Perception. 27, 1998, pp. 1209-1219.

- ^ A. Kitaoka, B. Pinna, G. Brelstaff: Contrast polarities determine the direction of Café Wall tilts. In: Perception. 33, 2004, pp. 11-20.

- ^ ME McCourt: Brightness induction and the Café Wall illusion. In: Perception. 12, 1979, pp. 131-142.

- ^ WA Kreiner: The Münsterberg deception. 2016. doi: 10.18725 / OPARU-4102

- ^ RL Gregory, P. Heard: Border locking and the Café Wall illusion. In: Perception. 8, 1979, pp. 365-380.

- ^ N. Wade: The Art and Science of Visual Illusions. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1982.