Monoglottogenesis

The term Monoglottogenese (from Greek μόνος monos "only, alone," γλῶττα glotta language and γένησις Genesis "creation") denotes within the paleolinguistics the assumption that all human languages have a common origin from a single source.

Within this controversial theory, attempts are made to identify common origins, primarily through language comparisons. Examples of this are the language family trees such as the family tree of the Indo-European language family . In this way, common origins could be identified for many languages, but not for all. Some of the language tribes have so little in common that they could also have arisen through contact between the respective peoples.

In the Middle Ages , based on the Bible, one simply assumed a monoglottogenesis, since the origin of all people was traced back to one person anyway. Consequently, his language was the original language . According to the place of origin of the Bible, Hebrew was also assumed to be the original language.

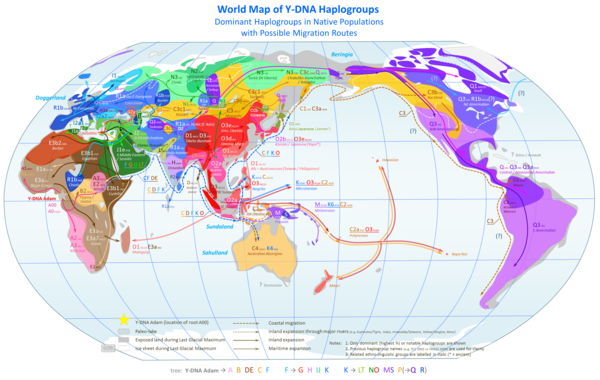

Based on the results obtained from research on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) but also on the haplogroups for the Y chromosome ( Y-DNA ), the probability of a monogenesis, and thus a common origin of all human languages, has become more probable. because modern man emerged from a very small group and they probably communicated via an agreed convention . However, it is not known whether this was a verbal language or whether the convention was more similar to the body language of today's apes.

On the other hand, it is assumed that other types of people, such as the Neanderthals , may already have spoken a language, since burial forms also included grave goods . Grave goods presuppose the abstract idea of a life in the hereafter. Such ideas can only have been conveyed through words, gestures or images.