Nabulsi soap

Nabulsi soap , Arabic صابون نابلسي, DMG Ṣābūn nābulusī , was a main export product of Palestine until the 20th century and established the prosperity of the city of Nablus . This olive oil soap is still made in the traditional way to this day.

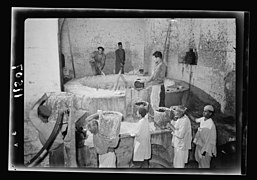

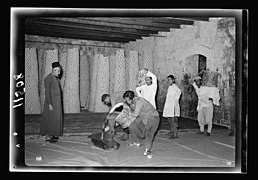

Production process around 1900

The production process common around 1900 in a soap factory ( meṣbane ) in Nablus was described by Gustaf Dalman :

The soap boiler ( ṣabbān ) bought alkaline vegetable ash (so-called Syrian potash) from Bedouins, which was pounded and sifted in a mortar with a wooden hammer. This was followed by mixing with slaked lime and adding water, while stirring with a hoe. The soap boiler filled the potash mass into troughs. His place of work was a large square recess with troughs on three sides; in front of it there were deeper-lying, narrow basins for receiving the liquid draining from the troughs. At first, the draining liquid was reddish, it was poured back into the troughs until clear liquid drained off. On the fourth side of the recessed workplace there was a so-called boiler ( ḥelle) with a metal bottom recessed towards the middle, which had a drainage channel to a narrow trough for the draining liquid. In the kettle, olive oil was brought to the boil with potash water, while potash water was constantly poured in, which was stirred in with a paddle. This process took six to seven days. During this period, an oily mass formed, which was brought in wooden vessels to an airy place with a limed floor, where it was poured out and smoothed evenly with a trowel.

An iron stick with a sharp tip was used to divide the layer into individual bars of soap. Several layers of bars of soap, piled on top of each other like a tower, dried for a year or two before they went on sale. Some of them were stamped. The soap was yellow, and green when dark olive oil was used.

The raw materials for a six-day soap-boiling process in Nablus were named as follows: 5000 kg olive oil, 50 kg soda, 60 kg water.

history

Soap making in Nablus can be traced back to the 14th century. Its prestige in neighboring countries stemmed from the fact that it was a pure olive oil soap with no added pork fat - an important point for Muslim customers.

Soap production in Nablus increased in the 1820s. The soap industry prospered, while other branches of the economy in Nablus stagnated due to European competition. This effect cannot be observed for other centers of soap production in the Syrian region (with the possible exception of Tripoli). Nablus benefited from the fact that the raw materials were produced in the area. There was a large olive-growing area here and the salt-tolerant barilla plant from which "Syrian potash" was made grew here.

Soap-making was capital-intensive: construction and maintenance of buildings and cistern-like olive oil stores, production of large quantities of soap, which could only be sold after one to three years. Therefore, the soap factories were initially jointly owned by several families, until the middle of the 19th century a process of concentration took place on a few owners who were able to finance the entire production process. The production process remained the same until the end of Ottoman rule and by and large up to the present day.

In the second quarter of the 19th century, after the intermezzo of Egyptian rule ( Tanzimat ), the Ottoman state began to exercise effective fiscal and administrative control in the Palestinian hill country. At the same time, this region (and thus also Nablus) was included in international trade. In particular, the taxation of olive oil, in addition to taxes on soap, posed a problem for soap producers. As olive oil from the neighboring area in Transjordan (Jamal Ajlun) was taxed less than olive oil from the Nablus region (Jamal Nablus), an incentive became an incentive created to use or declare this. Soap was one of the few products with which Palestine was present in international trade. When Egypt introduced taxes on imported soap in 1831, it was a severe blow to soap production in Jaffa and Ramla, which mainly processed linseed oil, coconut oil and peanut oil; The Nabulsi soap, on the other hand, was able to maintain and even expand its market share, as it was considered to be of particularly high quality.

The modern Shemen soap factory in Haifa, founded in 1922, actually produced a slightly different product, but there are indications that it competed with the producers of Nabulsi soap during the British mandate. Shemen soap was colored reddish, as Nabulsi soap had a reddish hue from brick dust; it was advertised as "as fine as Nabulsi soap," and the trademark - a menorah - signified that Shemen soap was free from pork fat. Like Nabulsi soap, Shemen soap was exported to Egypt and even Saudi Arabia, but this was probably mainly a disadvantage for the soap exports from Jaffa and Ramla. The British Mandate Authority exempted imported oil, which Shemen used to make soap, from import tax, which Arab critics called protectionism in favor of Shemen Ltd. designated. The British tax policy, combined with the size of the company and the wider range of products, made it possible for Shemen Ltd. At the end of the 1930s, undercutting the Nabulsi soap with his product.

Since the term Nabulsi soap was not protected by trademark law, there were many copycat products, especially Egyptian soaps. The Nablus family businesses tried to counteract this by registering their businesses and having their product names protected: Muftahayn (“Two Keys”), al-Jamal (“The Camel”), al-Naʿama (“The Ostrich”), al-Najma ( "The Star"), al-Baqara ("The Cow"), al-Badr ("The Full Moon"), al-Asad ("The Lion").

Workers in the Nablus soap factories started their own business in the 1950s by making "green soap" from the residues of olive oil production. The economic end for these small businesses came with the First Intifada , as they could not hold their own against the competition of industrially manufactured detergents, shampoos and imported branded soaps.

Some of the soap factories in Nablus are over 250 years old. During the Israeli reconquest of Nablus in April 2002, the historic building fabric in the city center suffered severe damage. Two 18th century soap factories ( al-Kanaan and al-Nabulsi ) were completely destroyed by fire from F16 rockets. In the Second Intifada , however, there was a backlash: Nabulsi soap was upgraded as a Palestinian cultural asset and its use was propagated as an act of resistance against the Israeli occupation.

present

In 2005 there were still three soap factories in operation: Tūqān , Masrī and Shakaʿa . 80% of the production was exported to Jordan, which was made easier by family relationships in the neighboring country. The continuation of the less lucrative family businesses is also a matter of prestige in urban society. While there was no modernization in the production method or in the packaging, the raw materials are different today: imported olive oil from Italy and caustic soda . The fact that Palestinian buyers belong to the older generation and value Nabulsi soap as a product from the “good old days” speaks against a new product design.

Palestinian NGOs, which have been dealing with cultural heritage since the 1990s, are pursuing a different approach: Nabulsi soap is to be made from Palestinian olive oil again and to that extent to tie in with tradition, at the same time the production process is to be modernized, making the soap more modern and for Tourists may get a more attractive design. Based on the model of Aleppo soap , the western market for natural products is to be opened up for Nabulsi soap. 2 to 3 tons of this soap were exported to Canada, Great Britain and France in 2005.

literature

- Beshara Doumani: Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700–1900 . University of California Press, Berkeley et al. 1995.

- Véronique Bontemps: Soap Factories in Nablus: Palestinian Heritage (turâth) at the Local Level . In: Journal of Balkan and Near-Eastern Studies , 2012. ( PDF )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gustaf Dalman: Work and Customs in Palestine , Volume 4, pp. 273-277.

- ↑ Beshara Doumani: Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700-1900 , Berkeley et al. 1995, p. 185.

- ^ A b Deborah Bernstein: Constructing Boundaries: Jewish and Arab Workers in Mandatory Palestine . State University of New York Press, Albany 2000, p. 119.

- ^ According to Dalman: Different types of Mesembryanthemum .

- ↑ Beshara Doumani: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700-1900: Rediscovering Palestine f, Berkeley, among others 1995, p 183rd

- ↑ Beshara Doumani: Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700-1900 , Berkeley et al. 1995, p. 187.

- ↑ Beshara Doumani: Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700-1900 , Berkeley et al. 1995, p. 188.

- ↑ Beshara Doumani: Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700-1900 , Berkeley et al. 1995, p. 216.

- ↑ Beshara Doumani: Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700-1900 , Berkeley et al. 1995, p. 225 f.

- ^ Deborah Bernstein: Constructing Boundaries: Jewish and Arab Workers in Mandatory Palestine , Albany 2000, p. 119 f.

- ↑ Véronique Bontemps: Soap Factories in Nablus: Palestinian Heritage (turâth) at the Local Level , 2012, p. 3f.

- ↑ Véronique Bontemps: Soap Factories in Nablus: Palestinian Heritage (turâth) at the Local Level , 2012, p. 4.

- ↑ Michael Dumper: Art. Nablus . In: Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley (Eds.): Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia . ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara 2007, pp. 265-268.

- ↑ Sherin Sahouri: The destruction of the old city of Nablus In 2002, . In: Simon Lambert, Cynthia Rockwell (eds.): Protecting Cultural Heritage in Times of Conflict: Contributions from the participants of the International course on First Aid to Cultural Heritage in Times of Conflict , 2010, pp. 53-59, here pp. 56.

- ↑ Nurhan Abu-Jidi: Threatened industrial heritage: the case of traditional soap industry Nablus, Palestine, 2006 . (Summary, KU Leuven)

- ↑ Véronique Bontemps: Soap Factories in Nablus: Palestinian Heritage (turâth) at the Local Level , 2012, p. 6 f.

- ↑ Véronique Bontemps: Soap Factories in Nablus: Palestinian Heritage (turâth) at the Local Level , 2012, p. 8 f.

- ↑ Véronique Bontemps: Soap Factories in Nablus: Palestinian Heritage (turâth) at the Local Level , 2012, p. 11 f.

- ^ Véronique Bontemps: Soap Factories in Nablus: Palestinian Heritage (turâth) at the Local Level , 2012, pp. 13-15.