New York Crystal Palace

The New York Crystal Palace was an exhibition palace in New York City that existed from 1853 to 1858 based on the London model of the same name . The building was built for the New York World's Fair of 1853, the " Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations ".

prehistory

The plan for an American "Crystal Palace" came from Edward Riddle , a Boston auctioneer and wagon builder who had looked after the American section in London. He gathered a group of New York bankers who had either attended the London exhibition or heard wonderful stories about it and were more than willing to invest in a similar project in the United States. The group of investors petitioned the board of New York City councilors for the use of Madison Square, in Lower Manhattan, where Broadway and Fifth Avenue meet on 23rd Street, to create an "iron and steel house for a Industrial exhibition ”. The petition has been granted and the necessary press releases issued. However, when residents around Madison Square found out about the project, there were many complaints that the aesthetics of the neighborhood would be ruined and that the building and traffic noise up until and during the fair was unacceptable. The case was brought before the New York City Chief Justice. The City Council's Board of Directors instead granted investors use of Reservoir Space located on 42nd Street between Fifth Avenue. This square was once home to Reservoir Park, which still exists today as Bryant Park and was named after William Cullen Bryant . It is also the current location of the New York Public Library , which was inaugurated in 1911.

Edward Riddle sold his stake in the project to other investors who began organizing the exhibition. This commission was a private corporation, but its members themselves had many political connections. Through Daniel Webster , the Secretary of State at the time, the new President of the Commission, Theodore Sedgwick III , was able to declare the future exhibition building as a bonded warehouse.

Joseph Paxton (1801–1865), architect of the London Crystal Palace, Leopold Eidlitz (1823–1908) who later built the New York State Capitol in Albany, James Bogardus (1800–1874) took part in the tender for the New York Crystal Palace. and his assistant, Hamilton Hoppin (1821–1885), who proposed perhaps the most exciting model. Bogardus he was a tireless fighter for the use of cast iron. His suggestion was a 300-foot tower with the roof suspended from chains. In the end, the commission decided on the design by the Danish architect Georg Carstensen , who was known from the Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, and his partner, the German architect Karl Gildemeister .

Rather than trying to outdo the Palace in London, the committee had recommended building a one-story structure on a budget of no more than $ 175,000. With the increasing number of registrations for the exhibition it soon became clear that the plans had to be laid out for a two-story building. Soon construction costs had risen to $ 200,000.

When the architect's plan was finally adopted in August 1853, the contracts for the masonry work and the foundation were awarded to Smith & Stewart and Mr. Lorenzo Mosis on September 25th. In order to match the individual cast iron arches and railings, the workshop of Messrs. Shepard & Purvis was set up in New York as a supervisor. The suppliers for this were divided between Messrs. Jackson, Stillman, Allen & Co., Hogg & Delamater, Buckup & Proh, and FS Claxton from New York; Slater & Steel in Jersey City; The Mattrawan Company of Fishkill; Messrs. Templins of Easton, Pennsylvania; Betis, Posry, Jones & Seal of Wilmington, Delaware; and Miller & Williamson in Albany.

Delays in construction

In the introduction to their book, the architects make a statement in which they describe why there were delays in the construction and why they were not to blame; z. B. the prices for iron had risen in the meantime and the foundries were waiting for a cheaper price. The engineer in charge made several attempts to build the dome, which lasted a few months, and was ultimately of the opinion that it should be built in London. That was of course unacceptable and would have meant further delay. The architects, who lacked liquidity, hired assistant engineer Mr. Kroehl, who supported the executing companies Messrs. Mott & Ayers and Hogg & Delamater in erecting the dome. A leak in the roof then caused additional excitement. In their “Introductory Statement”, Carstensen & Gildemeister point out that they - without an order from the Association - began to build the arcades for the machines, but they lacked the dimensions.

Description of the building

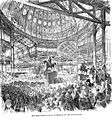

Reservoir Square is 3 ¼ miles from City Hall and is overshadowed on the east side by the massive walls of the Croton Reservoir. The base is based on a Greek cross surmounted by a dome. The length of each leg of the cross is 111.40 m and the width is 45.56. This does not include the three lobbies that lead out onto 6th Avenue, 40th and 42nd Streets and which are another 8.25 m wide and accessible by stairs. From the outside, the cross shape has an octagon, the diameter of which is the same as that of the arms of the cross. The triangular intervals were filled with single-storey 7.30 m high extensions to create more space for the exhibition.

The arrangement of the columns can be seen from the drawings. They divide the interior into two main aisles, each 12.65 m wide, with corridors 16.45 m on each side. The crossing of the ships allows an octagonal space of 30.5 m in diameter. The pillars further subdivide the triangular intervals between the arms of the cross into squares and half divisions with sides 8 m. The corridors are covered by galleries, which in turn unite in wide connections at the end of the ships. The galleries are supported by 16 semicircular arches made of cast iron, which are 12.5 m in diameter and 8 m apart.

The number of pillars on the main hallway is 190 pieces. They tower 6.5 m, are octagonal and have a diameter of 20.3 cm. The thickness on the sides varies from one ½ to 1 inch. The cast iron beams, 90 cm long, of which the longest is 8 m long, and the wrought iron with a length of 12.5 m are shown on the dotted lines. The first third of the girders support the floors of the galleries and reinforce the structure in all directions. They are connected to the pillars by 90 cm connectors. The number of carriers in the first third is 252 pieces. The second floor contains 148 columns with a height of 5.40 m, which rest on the lower and have the same shape. Above it is a second series of 160 girders that support the roofs over the aisles. They also have the semicircular arches of the ships. All roofs are supported by arches or girders using wrought iron inverted girders. The roofs are made of wood covered with zinc.

The dome, classy and beautiful in its proportions, is the main feature of the building. It has a diameter of 30.5 m, is almost 21.3 m high to the springing line and 37.5 m to the crown of the arch. This makes it the largest dome in the USA. It is supported by 24 pillars that lead over the second floor to a height of 18.80 over the main corridor. A system of wrought iron trusses connects them at the highest point and forms two concentric polygons, each with 16 sides. These are embedded in a cast-iron plate, into the shoe of which the cast-iron ribs of the dome are screwed. The number of windows is 32, which are securely connected with latticework. At the top, the ribs are screwed together to form a horizontal ring 6 m in diameter, which is crowned by a lantern through which light also falls. The windows are glazed with stained glass, which represent the coat of arms of the Union and a state and form part of the interior decoration.

The outer walls of the building are also made of cast iron, with the windows and the ventilation slots for ventilation. The glass was 1 inch (2.54 cm) thick and was made by Jackson Glass Works and then enamelled by Cooper & Belcher of Camptown, NJ The enamel is brushed onto the glass until it is covered, and kilned after drying. This makes the coating as durable as the glass itself. It produces an effect similar to ground glass, which is translucent but not transparent. The rays of the sun become diffuse light and thus pleasant and their intensity is taken away by heat and glare. New York had learned from the mistakes of the London exhibition where the windows had to be draped to provide shade.

At each corner of the building there is an octagonal tower with a diameter of 2.45 m and a height of 23 cm, which houses spiral staircases that lead to the galleries and to the roof. They are intended for use by the members of the Management Board and the employees. Twelve wide stairs, one each at the entrances and four under the dome, connect the main corridor with the galleries. The floor of the galleries consists of wooden planks. Above each entrance hall, the galleries lead onto balconies, which offer sufficient space for flower arrangements, vases and statues. On both sides of the entrances there is ticket sales and next to these rooms the telegraph connection for the members of the board.

The rapid and unexpected demand from applicants for showrooms forced the board to construct additional buildings, as mentioned earlier. They consisted of two parts of one and two story extensions and encompass the entire area between the main building and Compton Reservoir. The extension is intended for machines that are to be demonstrated in motion, the cabinets for minerals and mining as well as for refreshments with the required rooms. The entire second floor, which is 137 long and 6.5 m wide, is reserved for the exhibition of pictures and statues. It is illuminated by a skylight that is 127.7 m long and 2.60 m wide.

Henry Greenough from Cambridge, who had studied Italian art for many years, was commissioned with the decoration. His job was to beautify the building, which he succeeded. He mixed oil paint based on white lead paint from Belleville Co. The facade appears in a light bronze tone, in which all ornaments shimmer golden. Inside the building, a rich cream tone prevails, which was applied to all cast iron parts. This color was relieved by the moderate use of the three positive colors red, blue and yellow with a few shades of vermilion, garnet red, sky blue and orange, certain parts of the ornaments are gilded. The only exception to the oil paints is the dome, which was executed in tempera.

The dome was designed by Sr. Monte Lilla. From the center of the great dome, a golden sun sent its rays through a cluster of silver stars. The foliage along the balconies under the roof added a natural touch of the man-made beauty.

The whole building was provided with gas light everywhere and also with water. The gas light was intended for lighting in the evening and was also used to protect the building by the police in the dark. The drinking water came from the neighboring Croton Reservoir and was offered in numerous refreshment stations. But you could also connect hoses in case of fire.

The total amount of iron required was 1800 t, of which 300 t was forged and 1,500 t was cast iron. The amount of glass was 15,000 panes or 5110 m². 228,600 running meters of wood were used.

Christian Edward Detmold , Horatio Allen and Edward Hurry supervised the construction. Through a well thought out system, they used prefabricated parts made by 28 different iron foundries, such as: B. James L. Jackson, Daniel D. Badger, and the Novelty Iron works of Stillman & Allen. These pieces were put together on the spot.

The New York Crystal Palace Exhibition was opened with great ceremony on July 14, 1853 by American President Franklin Pierce and had around 5,000 exhibitors, about half of whom came from the USA.

The economy

As a financial venture, the New York Crystal Palace was a failure. By the time President, Theodore Sedgwick, finally resigned in 1854, $ 100,000 in unpaid bills had already been accumulated. The society was able to win PT Barnum for the new presidency in March 1854. He reopened The New York Crystal Palace and dedicated it to the working class. But even the great American entrepreneur was unable to save the Crystal Palace. Barnum resigned on July 1, 1854, and the new company had to close on November 1, 1854 with $ 300,000 in debt.

The interest in events in the "Crystal Palace" had slackened and the palace was, according to the "Times", a "dead property". The company was able to rent the building for a few concerts and conferences until January 1857. In May 1857 the city of New York took over the building.

The fire

On October 5, 1858, during the American Institute mass, a fire broke out in a junk room on 42nd Street. Approx. 2000 people were still in the building who, thanks to the heroic efforts of the fire brigade, could be evacuated. The building, which consisted almost entirely of glass and cast iron and a little wood, had been praised as "fireproof". Within 15 minutes the dome collapsed and within 25 minutes the entire building was in flames. There were no human sacrifices, but the material loss was significant. Fire losses were estimated at approximately $ 500,000 (today's value: approximately $ 12,802,150), including the building, as well as the exhibits and sculptures left over from the Exhibition of Industry of All Nations.

See also: Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations (1853)

Photo gallery

literature

- Statement Made by the Association for the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations , in Regard to the Organization and Progress of the enterprise . Publisher: Carr & Hicks, New York 1853

- Georg Carstensen, Charles Gildemeister: New York Crystal Palace: Illustrated Description of the Building . Publisher: Riker, Thorne & Co., New York 1854.

- The New York Crystal Palace: The Birth of a Building Inauguration. William R. Wallace (New York Times, July 14, 1853)

- William C. Richards: A day in the New York Crystal Palace and how to make the most of it : being a popular companion to the "Official catalog", and a guide to all the objects of special interest in the New York Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations. Publisher: GP Putman & Co., New York 1853

- Official awards of juries Publisher: Printed for the Association by WC Bryant & co. New York, 1853

- How to see the New York Crystal Palace: being a concise guide to the principal objects in the exhibition as remodeled, 1854 Publisher: GP Putnam & Co., New York, 1854

- - "- second part: catalog of picture gallery

- - "- Third Part: The Re-opening of the Crystal Palace with speeches

- Ursula Lehmkuhl : a_Kristallpalast_for_New_York_Kulturtransfer_und_nationale_Identitätskonstruktion_in_the_USA_vor_dem_Burgerkrieg A crystal palace for New York

- Ed Witkowski: The Lost History of the 1853 New York Crystal Palace: America's First World's Fair . Publisher: Vox Pop. Inc, 2008. ISBN 978-1-5989-91420

Web links

- Original description by the builder

- Exhibition in the Digital Gallery of the NYPL

- Concise Guide

- Guide to the New York Crystal Palace Records 1840-1858 in the New-York Historical Society

- The executing companies

- The State Committees In: Statement made by the Association for the Exhibition of the Industry of all Nations

- Six drawings by the architects - page 86 ff

- Additional drawings by the architects

Individual evidence

- Source: Description of the building - print from "Illustrated Record of the Exhibition" by Messrs. Geo PP Putman & Co. - page 5 ff

- ^ Statement made by the Association for the Exhibition of the Industry of all Nations

- ^ “Introductary Statement” by the architects G. Carstensen and C. Gildemeister of February 14, 1854 Page 9–22 ln: New York Crystal Palace: Illustrated Description of the Building

- ^ Letters of Horatio Greenough to His Brother, Henry Greenough . Edited by Frances Boott Greenough. Ticknor & Co., Boston 1887

- ^ Novelty Iron Works

- ^ New Board of Directors 1854

- ↑ Reopening of the Crystal Palace - from the New York Tribune May 5th, 1854

- ↑ American Institute, No. 351 Broadway, New York, July 20th, 1858

- ^ The Great Crystal Palace Fire of 1858 - Museum of the City of New York

- ^ New York Times : Other Burned Theaters . 7 December 1876, p. 10.

Coordinates: 40 ° 45 ′ 13.3 " N , 73 ° 59 ′ 1.7" W.