Pigou tax

A Pigou tax is a specific case of incentive taxes , ie taxes , less a fiscal purpose have, but rather serve primarily targeted steering of behavior. It is named after Arthur Cecil Pigou .

Pigou taxes serve only to correct a market failure by internalizing external effects . Since the market equilibrium is not Pareto-optimal in these cases , a Pareto improvement can be achieved through the use of Pigou taxes. In particular, the term Pigou tax does not include incentive taxes on actions that have no external effects, but that are socially undesirable for other reasons (e.g. moral or ideological).

The fiscal effect of a Pigou tax must not be calculated according to the level of the externality-generating act at the time the tax was introduced, since levying the tax is intended to reduce the harmful activity. This can also reduce tax revenue (see Laffer's theorem ). In other words, only the extent of the activity that is still being carried out when the tax is levied is fiscally effective.

In contrast to subsidies , Pigou taxes are burdensome steering purpose norms.

initial situation

A classic example is an economy made up of two producers on a river, a factory and a fisherman working further downstream. The factory discharges the wastewater generated during production into the river, which reduces the fisherman's profits (negative external effect ). Without regulation, the factory, in deciding how much to produce, will not consider the impact of its decision on the fisherman. This is macroeconomically inefficient, so the factory must reduce its pollution.

There are several ways to move the factory to lower production:

- A maximum set by the state would reduce the factory's production. However, this measure cannot be applied to an entire economy. Since every company causes different external costs, the state would have to set individual limit values - the effort would be too great.

- Trading emissions certificates would also limit the factory's production.

- If, following the example of Coase's theorem, one of the two parties were to be granted ownership of the river, an amicable solution would also be reached. From a macroeconomic point of view, it doesn't matter who owns the property.

- The state levies a Pigou tax.

Theoretical foundations of the Pigou tax

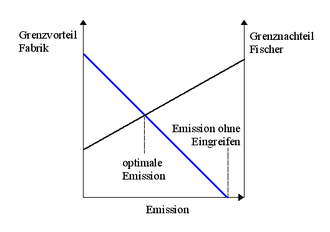

The state sets a tax per emission unit. The factory now has the option to either avoid a unit of emission or to emit it and pay the tax for it. A factory that maximizes its profit will produce until the marginal advantage of one emission unit equals the tax for it. Let t be the amount at which the cost of an additional emission unit at the fisherman exactly corresponds to its benefit for the factory. If the state specifies exactly this amount t as the tax , then the factory must fully take into account the costs of the fisherman and, ideally, will cause exactly the optimal amount of emissions (the external effect is completely internalized).

In cases of positive external effects , analogous to the Pigou tax, a state subsidy can have a higher side effect, which is desirable in this case ( Pigou subsidy ).

Application examples

Taxes that serve to steer the population rather than state revenue are z. B. the alcopop tax or the tobacco tax . However, the latter in particular has already been increased several times in the past in order to generate more tax revenue. In addition, in both cases not only external effects are to be named as the reason for the taxation, but from the point of view of the state it is also a question of so-called demerit goods , i.e. H. Goods whose benefits the consumer overestimates.

The German eco tax is often cited as an example of the Pigou tax. However, due to the nature of the eco-tax, this is only the case to a limited extent. Companies that use a lot of energy only pay a reduced rate. As the incentive to save energy is reduced for these companies, the Pigou tax principle has not been fully implemented.

criticism

The state needs precise knowledge of the course of the marginal utility and cost curves of those involved in order to set a tax at the optimal level. In addition, government failure can lead to a non-optimal level of Pigou tax.

In practice, it is often difficult to choose the emissions yourself as the tax base . In addition, only in the rarest of cases can external effects be precisely measured economically. If the state chooses a different basis, for example the goods produced or their value, then it is not necessarily guaranteed that the company will reduce the undesirable side effects of production to the required extent. A different amount of emissions can be agreed through renegotiations between the injured party (factory) and the injured party (fisherman). The fisherman pays the factory to reduce pollution even further, resulting in an overall loss of welfare .

The Pigou tax can violate the total condition of macroeconomic efficiency. Because companies tend to adjust quantities rather than price , the tax may lead to market exits.

In the case of an imperfect market, even welfare deterioration is possible. A monopolist would include taxes in his calculation and thereby avoid emissions, but at the same time reduce his production even further than he already does for reasons of profit maximization.

See also

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Andreu Mas-Colell, Michael D. Whinston, Jerry R. Green: Microeconomic Theory . 1st Indian ed. Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-19-510268-1 , pp. 356 .

- ^ Harold Demsetz: The core disagreement between Pigou, the profession, and Coase in the analyzes of the externality question . In: European Journal of Political Economy . Elsevier, December 1996, ISSN 0176-2680 , doi : 10.1016 / S0176-2680 (96) 00025-0 .

- ↑ AH Barnett: The Pigouvian Tax Rule Under Monopoly . In: The American Economic Review . American Economic Association, 1980, ISSN 0002-8282 .