Religion of ga

The traditional religion of the Ga in the southeast of today's Ghana is based on the ideas of a hierarchical world order with a supreme being, a subordinate world of gods and a multitude of rituals and festivals that are closely linked to the natural support of human life, i.e. H. with agricultural cultivation in the plains of the coastal hinterland or with fishing on the coast. In addition, religious rituals are also used to ward off diseases or other life-threatening conditions as well as to invoke and worship the ancestors.

World order of Ga

The world order of the Ga classifies all living beings into five hierarchical classes:

|

The classes and their main attributes in the cosmology of Ga |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rank | class | Ga designation | Attributes | ||||

| 1 | Supreme Being | Ataa Naa Nyongmo | live | creating | immortal | rational | movable |

| 2 | divine beings | Wong | live | created | immortal | rational | movable |

| 3 | People | Adesai | live | created | mortal | rational | movable |

| 4th | Animals | live | created | mortal | irrational | movable | |

| 5 | plants | live | created | mortal | irrational | immobile | |

Gods of Ga

Besides the supreme being Ataa Naa Nyongmo , who is the creator of all things, there are a multitude of other gods ( Wong ) among the Ga . The most important of them are:

- Nai

- Nai is god of the sea and "owner of the land". He is at the top of the hierarchy of the gods created by Ataa Naa Nyongmo . He is considered to be the father of all creatures in the sea ("father of the great whale") as well as the actual father of children on land. He is also the king of kings.

- Sakumo

- As the god of war and the divine protector of all Ga, Sakumo is one of their most important gods. The day of the week sacred to Sakumo is Tuesday.

- Naa Koole

- Naa Koole is the goddess of hunting and the goddess of peace. She is one of Sakumo's wives .

- Asham eels

- Asham eels are "our grandmother who was there before human beings existed".

- Dantu

- Dantu is the god of time and memory. He is (in terms of time) the first of the gods created by Ataa Naa Nyongmo .

- Naa Dede

- Naa Dede , also: Naa Ede , Naa Ede Oyeadu , is the patron goddess of birth.

- Gua

- Gua is the divine blacksmith who made the stars. He is associated with lightning.

- Ashiakle

- Ashiakle is the eldest daughter of Nai . She is the goddess of wealth.

- other divine children of Nai :

- Daughters of Nai (Naibi) : Amugi , Oyeni , Nyongmotsa , Oshabedzi , Osekan

- Son of Nai (Nainga) : Afieye

- more divine children of Sakumo :

- Daughter of Sakumo (Sakumobi ): Akrama ( Nii Akrama Opobi )

- more divine children of Naa Koole :

- Daughter of Naa Koole (Koolebi) : Obotu

- sound

- ?

Homowo

The Homowo ( Lante Dzan we Homowo ) is the festival of ancestor worship among the Ga. It is always celebrated on the Saturday that follows exactly 89 days after the Dantu shibaa , which introduces the Kpele rituals.

Especially in Accra you have the Accra Homowo , which takes place about two weeks later, or 103 days after the day of Dantu shiba . The Homowo festivals are not a form of the Kpele cult, even if the timing of the Kpele rituals is based on the Homowo festival, because the Danti shiba , with which the Kpele rituals begin, always takes place nine lunar months after the last Lente Dzan we Homowo festival.

For the Ga on the Mina coast (the Togo coast in the area around Anecho ) the Homowo festival is the annual New Year festival. It is an eight-day festival and is usually celebrated in the last days of September or the first days of October in direct connection with the Epe-Ekpe festival of the Ewe in Glidji and in a similar way to this. The connection to the Ewe festival is related to the golden chair of the Ga kept in Glidji .

Kpele

The main component of the traditional religious cult among the Ga consists of a group of rituals which are collectively referred to as kpele. These are individual rites that are closely linked to agricultural cultivation in the Accra plains or fishing on the coast, as well as to the personal fate of an individual. The aim is to maintain harmony in the relationships between gods and humans or to heal a state of disturbed harmony, i.e. H. restore. The existence of such harmony is seen as a prerequisite for human wellbeing.

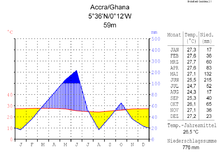

The Kpele cult is organized at the level of the individual We kinship groups, i. H. each We community forms a separate cult group. The Kpele rituals in their entirety affect all gods, which are addressed by them, but depends on the individual We group. The Kpele rituals associated with agriculture are based on the time of sowing and harvesting millet , the traditional main crop in the otherwise less fertile Accra plains. The climatic seasonal conditions in the area around Accra are characterized by a larger rainy season (April to July) and a smaller one (October) and according to them, sowing and harvesting between July and October are based, which ultimately is the time of the homowo and derived from it that of the Kpele rituals determined.

Priesthood

Responsible for the effectiveness of the rituals, d. H. there are two full-time specialists for their “correct” implementation: the Wolumo (priest) and the Wongtse . The latter is the medium through which a Wong being is addressed. Both act as mediators between mortals and the gods.

The priesthood is a male status linked to consanguinity, which is primarily linked to the representation of the goals and wishes of people. On the other hand, the medium quality is a feminine state that is connected with the establishment of communication between gods and humans and can only be achieved by certain (human) women. While the priest and Wongtse woman work together and appear together during the calendar rites , outside of this both can hold healing rituals independently of each other at any other point in time if there seem to be disharmonies between man and the world of the gods.

In a Kpele ritual, the medium assumes a two-valued state: on the one hand, of course, it remains a human being, which, however, appears as a divine communication tool. The fact that human women, of all people, and only women, are predestined to achieve this two-valued state has predominantly social reasons.

The vast majority of uneducated Ga women are in some form of retail trade and the chances of gaining wealth and influence are very slim. In addition, retail in today's Ghana is not a very prestigious institution anyway. Uneducatedness, manual clumsiness, etc. are the main sources of an objective social inferiority of a woman in the Ga society, both in the social and in the economic area. It does not matter whether those men who propagate and defend this inferiority with full conviction are uneducated or unskilled to the same or even greater degree. This is a general characteristic of Ga society.

It is therefore not surprising that this gives rise to the subjective urge for many women to gain reputation and influence by acquiring the ability to be a medium. In most cases, the path to this leads through the state of motherhood. Through motherhood, a woman herself becomes the founder of a new cognitive kinship unit, through which she can also achieve a certain social "immortality". With the establishment of a new kinship unit, there is also the choice of a wong as the deity of the new we . The founder can then qualify herself for her family deity through a certain training as a medium. There is always only one wong for which a woman can act as a medium. As for choice, there is a belief that each divine being chooses its own personal medium. Once a divine choice has been made, it is irrevocable.

The woman chosen as the medium does not necessarily have to be a member of the cognitive kin group whose cult is directed towards this god. It just establishes the connection in the form of a service. That is of immense social importance. On the one hand, it ensures the presence of media in the kinship groups and, on the other hand, it offers a kind of development potential for the construction and design of a social network.

To achieve the medium quality, the woman has to complete a tedious, long and expensive training. Once chosen as the future medium, it is believed that refusal to do so would be punished with madness or death. According to the Ga, there is a marriage-like relationship between the Wong and his medium, which is also monogamous. That is, every God has only one medium within a We . Only when the medium dies is a new one chosen.

The main aspect in the role as a medium is the transmission of messages between gods and humans. For this it is necessary that the divine Wong take possession of his medium, i.e. H. is temporarily localized in the body of the medium, which only takes place if the corresponding ceremonies in connection with ritual chants and dances have been preceded. The Wong uses the body of the medium in such a way that he hears the messages of the people or speaks to them through the mouth of the medium.

This "slipping into the body" is also viewed as divine cohabitation. The medium possessed by God performs ritual chants ( Lala ) and dances ( Dzoomo ), which it has learned during the training period in connection with extensive voice training. The dances also require a certain degree of training and are controlled and performed with high concentration. A “trance” state, as is common in other societies, is not created here, although herbal mixtures of a secret composition are not dispensed with. Expressions of the deity are mostly spoken and seldom occur as chant.

In conjunction with personal problems of a person or in matters of redress for an individual, laden with guilt people a medium-woman can also place of Wong the shadows of the ancestors or the spirits of twins call. In the event of a demand for reparation, the special, angry ghost slips into the medium and explains to the person in question the reason for his anger and how it can be appeased again. Most of the time, the mind demands that a reparation ritual be held at the next opportunity, but this can only be carried out through the medium.

Any spiritual activity that a medium woman is entrusted with requires payment. Those who have no money pay with food or the like.

During the state of possession, the medium speaks not only with authority as a spokesperson for divine beings, but also with complete personal impunity. In this regard, the medium women are of immense social importance and it is therefore also a concern of the long training in advance to generate the highest possible degree of psychological and social acumen in her, because after all she has a certain individual scope in relation to it for possible rewards or punishments within their following. A medium status also allows women to develop and live out individual interests and talents which they otherwise cannot discover or can only develop very imperfectly due to their lack of education. Older medium women are encouraged to train offspring. The completion of the training of a medium novice depends not only on her talents and the skills learned, but primarily on the ability and willingness of her relatives to pay the fee required by her teacher for the training, which is usually very high .

During the apprenticeship, the novice lives with her teacher and is asked to adhere to various diets and sexual prohibitions, and must also do the housework on the side. The aim is to create a close and lasting social relationship between teacher and pupil, which is why the novices call their teacher Awo (mother) and the teacher gives her pupil her own names that she would otherwise have given her own biological children. After the death of a teacher, at the annual Homowo, her soul is given as much veneration by her pupil as it is given by the ancestors.

Kpele calendar

As an example of a Kpele calendar, the one for the year 1968 is shown here:

|

Example: Kpele calendar in Accra in 1968 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| designation | reserved weekday |

fell on the in 1968 |

Interval after the Dantu shibaa |

| 1. Rites relating to agriculture | |||

| 1.1.) Shiba rites (relating to soil preparation) | |||

| Dantu Shibaa | Monday | May 13, 1968 | - |

| Sakumo Shibaa | Tuesday | May 14, 1968 | 1 day |

| Naa Koole Shiba | Friday | 17th May 1968 | 4 days |

| Gua Shibaa | Saturday | May 18, 1968 | 5 days |

| Naa Ede Shibaa | Sunday | May 19, 1968 | 6 days |

| Nai Shibaa | Tuesday | May 21, 1968 | 1 week 1 day |

| 1.2.) Ngmaadumo rites (concerning the sowing) | |||

| Dantu Ngmaadumo | Monday | May 20, 1968 | 1 week |

| Sakumo Ngmaadumo | Tuesday | May 21, 1968 | 1 week 1 day |

| Naa Koole Ngmaadumo | Friday | May 24, 1968 | 1 week 4 days |

| Gua Ngmaadumo | Saturday | May 25, 1968 | 1 week 5 days |

| Naa Ede Ngmaadumo | Sunday | May 26, 1968 | 1 week 6 days |

| Nai Ngmaadumo | Tuesday | May 28, 1968 | 2 weeks 1 day |

| 1.3.) Ngmaaku rites (concerning the 1st harvest) | |||

| Dantu Ngmaaku | Monday | June 10, 1968 | 4 weeks |

| Sakumo Ngmaaku | Tuesday | June 11, 1968 | 4 weeks 1 day |

| Naa Kooke Ngmaaku | Friday | June 14, 1968 | 4 weeks 4 days |

| Gua Ngmaaku | Saturday | June 15, 1968 | 4 weeks 5 days |

| Naa Ede Ngmaaku | Sunday | June 16, 1968 | 4 weeks 6 days |

| Nai Ngmaaku | Tuesday | June 18, 1968 | 5 weeks 1 day |

| 1.4.) Odada rite (Welcome, you gods of the field!) | |||

| Odada | Tuesday | June 20, 1968 | 5 weeks 3 days |

| 1.5.) Ngmaaku rites (concerning the 2nd harvest) | |||

| Dantu Ngmaaku | Saturday | August 10, 1968 | 12 weeks 5 days |

| Sakumo Ngmaaku | Tuesday | August 27, 1968 | 15 weeks 1 day |

| Nai Ngmaaku | Tuesday | August 27, 1968 | 15 weeks 1 day |

| Naa Koole Ngmaaku | Friday | August 30, 1968 | 15 weeks 4 days |

| 1.6.) Ngmaayeli rites (harvest festival) | |||

| Dantu Ngmaayeli | Sunday | August 11, 1968 | 12 weeks 6 days |

| Naa Koole Ngmaayeli | Friday | August 30, 1968 | 15 weeks 4 days |

| Sakumo Ngmaaku | Tuesday | 3rd September 1968 | 16 weeks 1 day |

| Nai Ngmaayeli | Tuesday | 3rd September 1968 | 16 weeks 1 day |

| Sakumo Ngmaayeli | Tuesday | September 10, 1968 | 17 weeks 1 day |

| Nai Ngmaayeli | Tuesday | September 10, 1968 | 17 weeks 1 day |

| Salumo Ngmaayeli | Tuesday | 17th September 1968 | 18 weeks 1 day |

| Amugi Ngmaayeli | Tuesday | 17th September 1968 | 18 weeks 1 day |

| Obotu Ngmaayeli | Tuesday | 17th September 1968 | 18 weeks 1 day |

| Oyeni Ngmaayeli | Tuesday | 17th September 1968 | 18 weeks 1 day |

| Nyongmotsa Ngmaayeli | Thursday | 19th September 1968 | 18 weeks 3 days |

| Oshabedzi Ngmaayeli | Thursday | 19th September 1968 | 18 weeks 3 days |

| Nai Afieye Ngmaayeli | Friday | 20th September 1968 | 18 weeks 4 days |

| Gua Ngmaayeli | Saturday | September 21, 1968 | 18 weeks 5 days |

| Osekan Ngmaayeli | Sunday | 22nd September 1968 | 18 weeks 6 days |

| Akrama Ngmaayeli | Sunday | 22nd September 1968 | 18 weeks 6 days |

| Sounded Ngmaayeli | Sunday | 29th September 1968 | 19 weeks 6 days |

| Ashiakle Ngmaayeli | Sunday | 29th September 1968 | 19 weeks 6 days |

| 1.7.) Mangnaamo rite (dance at the Sakumo shrine) | |||

| Mangnaamo | Wednesday | 18th September 1968 | 18 weeks 2 days |

| 1.8.) Ngmaatoo rite (concerns the storage of the grain and its protection by the children of Sakumo) | |||

| Ngmaatoo | Tuesday | 1st October 1968 | 20 weeks 1 day |

| 2.) Rites relating to fishing | |||

| Opening of the Koole Lagoon (for fishing) |

Friday | 17th May 1968 | |

| Closure of the Koole Lagoon (for fishing) |

Friday | June 14, 1968 | |

|

Ngsho bulemo (opening of the sea for fishing) |

Tuesday | August 6, 1968 | |

| Opening of the Koole Lagoon | Friday | 23rd August 1968 | |

| Closure of the Koole Lagoon | Friday | 4th October 1968 | |

| Opening of the Koole Lagoon | Friday | December 27, 1968 | |

| Closure of the Koole Lagoon | Friday | 7th February 1969 | |

| 3.) Homowo (festival of the ancestors, actually not a part of Kpele) | |||

| Lante Dzan we Homowo | Saturday | August 10, 1969 | 12 weeks 5 days |

| Accra Homowo | Saturday | August 24, 1969 | 14 weeks 5 days |

Development of a calendar Kpele ritual

A Kpele ritual, if it is related to agricultural cultivation, essentially consists of five sections or acts:

1.) Introduction at the Shrine of God

- Here, magical water is prepared and a symbolic cleansing of the celebrants is carried out, including a drink offering for the respective god.

2.) Procession to the field to be ordered

3.) Ritual in this field

- There is another libation for the god in question and the subsequent execution of the field work related to the Kpele ritual:

- During the Shibaa ritual: working the soil in preparation for sowing

- in the Ngaadumo ritual: sowing

- in the Ngmaafaa ritual: thinning or transplanting of sprouts

- in the Ngmaaku ritual: harvest

4.) Return to the shrine

- Here, an invocation of the god through the medium takes place in connection with a request that is connected with the purpose of the ritual (e.g. with the sprouting of the seeds, a good harvest, etc.). When you return to the shrine, a final ritual takes place with new libations, after which guests are greeted and treated with food and drink.

In the case of harvest, the crop is then distributed.

Other rituals

In Accra e.g. B. 38 additional non- Kpele rites are added, which take place every year from July to September and which, for example, represent yams festivals for certain chiefs' chairs or for certain sub-gods. Each deity has a specific, sacred day.

Footnotes

- ↑ "Shika" means money or gold in the Kwa language of the Ga. "Sika" also means gold in the Twi language of the neighboring Akan peoples.

- ↑ The time information is confusing. Nine lunar months are exactly 265 days + 18 hours + 36 minutes. + 27 s. long. Adding 89 days results in exactly one lunar year with 354 days. How the difference to the tropical solar year is ultimately compensated for is unclear, because the Homowo is no or only a movable festival in an extremely short time frame.

- ↑ A We community is a cognative kinship group among the Ga. The individual cognates define themselves as those persons who are related by descent from the same parents (cognation = blood relationship). In addition, this term is also extended to the persons of the female (matrilineal) blood line, i.e. H. to persons who by descent from a common ancestress related forth.

- ↑ As a rule, it is Rispenhirse the type Panicum miliaceum (L.) , on Ga as Ngmaadumo referred, or sorghum .

- ↑ Even if there is compulsory schooling for children aged 6 to 12 in today's Ghana (2001), the illiteracy rate is still relatively high today.

- ↑ It could e.g. B. all women in a We community die and none would then be left to communicate with the Wong .

- ↑ z. B. in relation to herbalism, singing lessons, psychology studies etc.

- ↑ A chair identifies the institution of an office itself and the owner of the chair is the holder of the office, in this case the chief. As a rule, chairs are tied to families; H. the occupation is regulated within a specific family. But chairs also have religious elements, e.g. they serve as shrines to the ancestors or similar.

literature

- Marion Kilson: Ambivalence and power: mediums in Ga traditional religion , in: Journal of religion in Africa , 4 (3), 1972, 171–177

- Marion Kilson: Taxonomy and form in Ga ritual , in: Journal of religion in Africa , 3 (1), 1970, 45-66