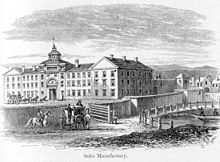

Soho Manufactory

The Soho Manufactory was one of the first modern factories built in Handsworth (now a borough of Birmingham ) between 1762 and 1765 by entrepreneur Matthew Boulton and his partner John Fothergill and existed until 1842. The manufactory became famous on the one hand because it was the first time that machines were consistently used for the mass production of goods, and on the other because it also became a model for social working conditions: Boulton built his workers' houses on the site and designed the workshops to be clean, light and airy , prevented child labor (according to the standards of the time) and introduced social insurance based on the principle of solidarity.

History of the manufacture

Before the Soho Manufactory was established, Boulton already had a factory for handicraft jewelry; especially for buttons, belt buckles, snuff boxes and the like. It was organized like most factories of its time: the individual work steps were carried out in workshops that were housed in the homes of the craftsmen. The workpieces were transported to the next home workshop for the next work step; As the workpieces were often made of silver or other valuable materials, separate guards had to accompany the transport through the city. This led to a high expenditure of time and money in production. Since the competitive pressure in Birmingham was very high at the time, Boulton tried to reduce costs by planning a production facility in which all production steps were housed on a single site. He took this idea from his competitor John Taylor , who had already organized a production facility in Birmingham in this way in 1759.

founding

To convert his production methods, Boulton needed a suitable site, which he found in 1761 in a northern suburb of Birmingham, the village of Handsworth. Here, on a hillside property, stood a water mill by a reservoir. The watermill had a plot of around four hectares with a few buildings on it, as well as the water rights that secured the mill. For £ 1,000, Boulton acquired the original tenant's 99 year lease and all of the buildings on the property at Hookley Brook , which he promptly demolished. Instead, he opened a clay pit on his property, built a brick kiln and built his new workshops, houses for workers and a new water mill from the bricks.

In the course of 1761, both the need for additional capital and the need to have a site manager on site became apparent. The entrepreneur John Fothergill was recruited as a partner; Fothergill contributed £ 5,394 and 16 shillings in cash to the partnership, and Boulton's stake in the firm was £ 6,206, 17 shillings and 9 pence in cash, materials, land and buildings. Fothergill moved into the already completed mansion on the site, the Soho House , which still exists today , and supervised the construction work, while Boulton stayed at his previous production site at Snow Hill and continued to run business there.

Between 1762 and 1764, most of the workshops, workers' houses and machine shops were built on the site. All the buildings were bright and well ventilated; later Boulton had clean workrooms and freshly whitewashed buildings regularly taken care of. His goal was to create a healthy and as pleasant as possible working atmosphere. He consciously followed Rousseau's ideas of a humane existence and presented his manufacture accordingly in public. This led to a great deal of public attention and high-ranking visitors who wanted to convince themselves of the working methods in the factory. This publicity in turn made Boulton's business easier, especially exports.

The central main house, which became the symbol of the manufactory, was not built until 1764. It was a three-story building with a central, two-story passage into an inner courtyard and an octagonal clock tower. The facade design was based on classicist templates by Andrea Palladio . Machine halls, workshops and studios were set up on the lower two floors, while the top floor was furnished with apartments for executives. Two lower wing structures that enclosed the inner courtyard also housed workshops. In the workshops of the central building, a large number of machines were built to relieve the workers of heavy work as much as possible and at the same time to ensure consistently high quality of the products. The arrangement of workshops and machines allowed for the first time a type of production line that is common in factories today. The cost of the main house rose from originally £ 2,000 in the planning phase - an unusually high sum for a factory building at the time - to £ 10,000 upon completion. These funds were raised through a large loan from London publisher Jacob Tonson .

When the factory opened in 1765, according to Fothergill, 400 workers and their families lived there, while Boulton said 700 workers were employed. Boulton's statements are a little less credible than Fothergill's figures on this point because he placed a high value on a good public image; presumably he was exaggerating the real numbers.

Production and extensions

Initially, the range of small jewelry - buttons, boxes, sword knobs, etc. - already known from Snow Hill was produced in the Soho Manufactory . The principles of increasing quality through the use of machines and reducing costs through mass production quickly proved their worth. Thanks to the additional possibilities of the system, Boulton was able to greatly expand its range: in addition to the development and use of silver plating ( Sheffield plate ), fashionable reproductions of antique vases and medallions designed in their own studios were made from various materials. The fashionable materials used included black ( blue John , ormolu and black basalt ) earths, which were particularly well suited for emulating classicist vases. His fiercest - and much more successful - competitor in this field was Boulton's friend Josiah Wedgwood , who in 1769 opened his own factory town called Etruria for his ceramics. Wedgwood and Boulton worked together, however, by Wedgwood sending smaller pieces from Etruria to Soho to have them produced there in metal. Precision mechanical works such as the philosophical clocks series - clocks showing sidereal times and planetary positions, developments by the famous watchmaker John Whitehurst - were also produced in Soho.

From 1767 onwards, Boulton considered equipping the factory with steam engines that would complement the water-powered rolling mill and mechanize other heavy work. At first, Boulton rejected the only economical high-pressure steam engines because they were very unsafe due to the materials and types of connection used at the time and occasionally exploded. Only when Boulton got to know the design of a low-pressure machine by James Watt did he get closer to the idea. For legal reasons, however, concrete implementation began in 1772.

The shortage of change in early industrial Great Britain and the progress in the construction of steam engines prompted Boulton first to develop minting machines, then to found the first machine-operated mint, the Soho Mint , which he built on the site of the Soho Manufactory in 1778 . It quickly became very successful because it was able to produce large quantities of almost forgery-proof coins of consistent quality in a short time. A special feature was the low share of production costs in the coins due to the consistent use of machines and automated processes, which made the mass production of low-value coins possible in the first place. The Soho Mint is a prime example of the use of machines for the mass production of goods during the early industrial revolution.

When in 1795 the money was available to manufacture their own steam engine, it became clear that the space on the Soho Manufactory site was insufficient for an additional foundry. About one kilometer further west, on the city limits of Smethwick , another site was acquired and the Soho Foundry was built there, in which the Boulton & Watt company successfully set up its own steam engine production.

Boulton's successor and the end of the Soho Manufactory

After Fothergill's departure (1781) and Boulton's retirement into private life in 1800, the company passed to the sons of Matthew Boulton and James Watt. They reduced the social benefits of the company, which had always worked on the verge of profitability, at first very sharply and later eliminated them completely. The guided tours that Boulton had set up, which increased the popularity of the products, were also discontinued. Major innovations were no longer introduced. After the death of the two sons, the Soho Manufactory was closed in 1842.

Between 1848 and 1863, the manufactory's buildings were demolished, with the exception of Soho House, which now serves as a museum. The area was rebuilt with residential houses and workshops. Three days of excavations as part of a television series on archeology in April 1996 uncovered the foundations that made it possible to reconstruct some buildings.

Effects on society and manufacturing

The Soho Manufactory is considered to be the first consistent and successful implementation of the principles of mass production: mechanization of the work processes, work lines and concentration of the work steps on a specially set up company site replaced the home workshops that had been common up until then, in which entire families carried out individual production steps by hand. Due to the local concentration of work, machines could take on heavy work on the one hand and repeat individual work steps with high precision on the other. This reduced production costs and at the same time increased the quality of the goods.

Boulton's guided tours through the factory halls, which he also presented to high-ranking politicians and scholars from around the world (such as Benjamin Franklin in 1771, Georg Christoph Lichtenberg in 1775 and Lord Nelson in 1801) quickly spread the knowledge of work organization in all the emerging industrial nations and were immediately imitated there .

The social achievements that had been realized in the manufactory - human working conditions, no child labor, mutual social security - did not prevail. They were already discontinued by the successor of the company founder and only slowly introduced in the industrialized nations from around 1850.

References and comments

- ↑ E. Robbinson: Boulton and Fothergill hardware 1762-1768 and the Birmingham Export of. University of Birmingham Historical Journal VII, no. 1 (1959); quoted in Jenny Uglow: The Lunar Men . 2nd Edition. Faber and Faber, London 2003, ISBN 0-571-21610-2 , pp. 521 .

literature

- Jenny Uglow : The Lunar Men . 2nd Edition. Faber and Faber, London 2003, ISBN 0-571-21610-2 .

- Chris Upton: A History of Birmingham . Phillimore & Co, Chichester / Sussex 1993, ISBN 0-85033-870-0 .

- Golo Mann (Ed.): Propylaea World History . tape 8 : The nineteenth century . Propylaen Verlag, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1960, ISBN 3-549-05017-8 .

Web links

Coordinates: 52 ° 29 ′ 56 " N , 1 ° 55 ′ 34.7" W.