Matthew Boulton

Matthew Boulton (born September 3, 1728 in Birmingham , † August 18, 1809 in Birmingham) was an English engineer , medalist and entrepreneur of the early Industrial Revolution . Together with James Watt, he developed and sold steam engines. Influenced by Joseph Priestley , Thomas Day, and other friends close to the thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau , Boulton introduced social security for his employees in his factories .

life and work

Youth and beginning business life

Boulton was the second son of the entrepreneur Matthew Boulton Sr. Born in his parents' house in what was then Whitehouse Lane (now Steelhouse Lane ). His father ran a toymaker on Snow Hill, a factory for high-quality metallic decorations such as buttons and sword scabbards.

Boulton was taught at the Birmingham Public School, but also relied on his father's large library. The then fashionable experiments with electricity and batteries, which his father undertook like many educated people of his time, further fueled his thirst for knowledge. Without having studied, he quickly became familiar with almost all the scientific areas of his time, but focused on the application of the sciences in metallurgy . In his notebooks there are many ideas and processes that he had developed or significantly improved with the aim of optimizing his father's production methods. Boulton left school when he was 17 and joined his father's company. On his 21st birthday, he named him an equal partner.

In February 1749, six months earlier, Boulton had his distant cousin Mary Robinson, the daughter of the wealthy landowner Luke Robinson Sr. married in Lichfield . Mary brought into the marriage a large inheritance (not quantified in the sources) that she had received from her godmother. When her father died in 1750, she inherited a further £ 3,000 (around € 300,000 in today's value). In addition, Mary was entitled to an additional £ 14,000 (approximately € 1.5 million) from the family estate after her mother died. This laid the financial foundation for the fulfillment of Boulton's entrepreneurial ambition: according to the marriage law of the time, the woman's assets fell to her husband when they married. In August 1759, Mary also died unexpectedly, possibly of puerperal fever, and was buried in the family grave in Whittington.

In the same year as Mary, Boulton's father died. As a result, he became the sole owner of the joint company, whose fate he had already largely determined since 1757. The father's workshops on Snow Hill became too small, but the inherited fortune was not enough to ensure the continued existence of the company.

Less than a quarter of a year after Mary's death, Boulton began soliciting her sister Anne. He successfully sought his mother-in-law's approval. In contrast, his brother-in-law Luke rejected him as a dowry hunter. Anne's mother fell seriously ill in May 1760 and died shortly thereafter, leaving Anne with an inheritance of around £ 28,000. Boulton adopted old English law, “kidnapped” his bride to London and married her on June 25, 1760. Then the couple hid from everyone for four weeks. After that, the objection period had passed and the marriage was inseparable according to ecclesiastical and secular law. The couple moved into Boulton's house in Birmingham.

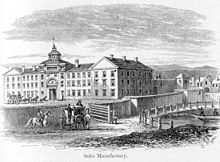

The Soho Manufactory - From workshops to factories

→ Main article: Soho Manufactory

The additional financial means enabled Boulton to realize his plans for a new, larger manufacture. In order to increase work efficiency, Boulton wanted to create a central building for all work. His competitor John Taylor had already realized this idea with some success in 1759, also in Birmingham. Boulton copied and expanded the concept to include the possibility of central machine use, which supported and in part made mass production such as Boulton had in mind.

Three kilometers northwest of Birmingham, near the village of Handsworth, a suitable piece of land was found that Boulton leased. He had the existing buildings demolished and new production buildings, a rolling mill and a workers' settlement built. An existing mansion, Soho House , was converted into a control center for monitoring construction work and was later replaced by a new building. Since the work was time-consuming and expensive, but at the same time work on the old production facility in the Snow Hill district continued, Boulton took on a partner in the company in 1762 who took over on-site construction supervision. With this partner, John Fothergill , he ran the manufacture until 1781.

By 1764 most of the buildings had been erected and production began. His experience with the centralization of machines led Boulton to plan another building, which not only included machine rooms, studios and apartments for the families of the executives, but was also designed as a representative building with a two-story passage and a clock tower. When the required money was available in 1764, Boulton had his plans implemented. This building became the symbol of the Soho Manufactory , which was officially opened in 1765 and quickly attracted high-ranking visitors from all over the world, who quickly carried the idea of a central factory building with machinery to many countries.

Soho Manufactory became a model for other factories that concentrated all the necessary workplaces and machines on their premises; so Boulton worked on the planning of his friend Josiah Wedgwood's factory town , Etruria . The factory's financial success was not consistent, though Soho work was popular across Europe and the overseas colonies of England. Rather, Boulton was constantly experimenting with new, very expensive machines in his factory, which put the Boulton & Fothergill company under great strain and often brought it to the brink of ruin. While Boulton was able to offset his money from other ventures, such as the rental of steam engines, his partner Fothergill was unable to repay the loan taken out for the partnership. This was not taken over by Boulton until 1782, after Fothergill's death.

As a last step towards concentrating the work processes, Boulton was able to persuade the London calibration office to set up an offshoot in Handsworth in 1773, where the precious metal content of his products could be checked and certified.

For all the public encouragement, the fact that Boulton had arbitrarily and without financial compensation extended the boundaries of the land he had leased to part of the common pasture of the village of Handsworth was benevolently ignored . This was not a mistake or an accident, as a letter written by Boulton himself 25 years later shows, in which he depicts the taking possession as a charitable act because it would have provided a clean, healthy home for a thousand workers where only a few ragged villagers had previously passed Theft and this common pasture would somehow have perished their lives. He would recommend this approach. Such “wild privatizations” of community land to the detriment of the poor sections of the population were widespread in Boulton's day and even had their own name (“ enclosures ”). However, these areas were otherwise used for intensive agricultural cultivation. Boulton's approach was unusual.

Boulton & Watt - "what all the world desires to have: power"

→ Main article: Boulton & Watt

Now that the factory was up and running and, within a very short period of time, had become widely known throughout Great Britain for the quality and affordability of the products it produced, Boulton began to think about increasing the efficiency of his machines. The hydro-powered devices were slow and weather dependent. In addition, they could only be set up in places where a watercourse could be dammed. This limited the use of machines considerably.

As early as 1762 Boulton's friend Erasmus Darwin , the family doctor of his wives’s family, corresponded with Boulton about a steam-powered locomotive , albeit under the seal of secrecy. The experiments did not lead to any useful results, but Boulton found the solution to his problem in this project: steam engines . They could be set up anywhere and were independent of the weather.

The useful designs used steam overpressure to move a piston which then did the work required. However, due to the processing technology at the time, the devices could not always withstand the pressure and exploded. Boulton therefore ruled out these machines as unreliable.

The engineer Thomas Newcomen had developed another type of construction for steam engines around 1710 : the vacuum steam engine. Here the steam was fed into the chamber with the piston and condensed there. This created a vacuum that moved the piston. However, these machines were very inefficient because they were subject to an unsolved structural problem: the steam chamber had to be cool in order to generate the vacuum through the condensation of the steam, but the piston had to remain hot in order to use the energy of the steam. Despite their inefficiency, vacuum steam engines were used because they were able to pump out the groundwater that penetrated the shafts in mining. Due to their construction, they could work safely and continuously without bursting, thus guaranteeing that the pits would not be flooded. Due to their very high fuel requirements, they were very expensive to maintain.

The Scot James Watt had found a solution to this problem . He expanded the vacuum range by adding a separate chamber in which the steam could condense without the main chamber having to be cooled with the piston. In April 1765 he built a functional model of his idea of a steam engine with a separate condenser, which now had to be converted into a large functional machine. Through the mediation of a friend, he found financial support from the coal mine owner and iron producer Dr. John Roebuck , who wanted to increase the efficiency of his Newcomen machines. He offered Watt funding for his research. In return, he wanted to receive two thirds of the rights to the steam engine. Watt agreed.

But what worked in the model could not be transferred into practice. In 1766 Watt had to give up his attempts to create a functioning machine for the time being. But his work with cheaper models yielded new ideas that made Watt's steam engine increasingly powerful and efficient. So he alternately directed steam into the piston tube and thus not only saved the mechanical mechanism that brought the piston back to its original position, but also achieved more and more uniform performance with again lower energy consumption. On August 9, 1768, Watt filed a patent for its design, which was granted the following year.

Roebuck, who had paid for the construction for Watts, and Boulton, the aspiring businessman from Birmingham, were business partners. Before long, Boulton learned of Watts' experiments and ideas. Boulton showed interest in purchasing Watt's ideas, but Roebuck only offered him a license agreement, which Boulton refused. Instead, he contacted Watt to inquire directly from the inventor about the possibilities of his design. From 1768 the two were in contact with each other, who quickly changed from a business to a friendly basis. Boulton openly admired his new friend Watt's genius and ingenuity to his friends, while Watt praised Boulton's philanthropy and business acumen. With both the respect lasted to the end of their lives; After Boulton's death, Watt will assure you that in 35 years of close cooperation they would not have had the slightest difference.

When Roebuck got into economic turmoil, he borrowed £ 1,200 from Boulton, which he owed until his bankruptcy in 1772. Boulton held himself harmless by taking two-thirds ownership of Watt's patent. In the same year Watt's first wife died; the inventor then moved to Birmingham.

Together, the two friends planned a new factory, this time not for buttons but for steam engines. They decided to have the individual parts of their steam engines manufactured and delivered by subcontractors, and in 1775 they founded their joint company: Boulton & Watt . Both partners had equal rights, which means: Boulton gave up his two-thirds majority in the patent and only claimed a 50% stake. He used his relationships with members of the British Parliament and obtained an extension of the patent from 6 to 30 years. Boulton and Watt subsequently successfully hindered the further development of the steam engine by competing engineers. They sued the inventor of the Hornblower steam engine, which made higher efficiency possible, for patent infringement and were thus able to stop further development.

Watt's steam engine was about four times more powerful than its predecessor and was used by mine owners to keep their tunnels free of groundwater . As Watt was overwhelmed by the amount of work, the friends looked for another creative designer. They found him in 1777 in the person of William Murdoch , also Scotsman like Watt. Murdoch enriched the company with a variety of improvements to existing designs and with completely new inventions. Finally, Boulton & Watt brought out a variant of Watt's steam engine, with which the previously exclusively linear movement of the drive was converted into rotation . This meant that the machine could be used almost anywhere for any conceivable task; the industrialization of Great Britain, which had already started , thus got its decisive impetus. By 1790 there were more than 500 Boulton & Watt steam engines in the mines and factories on the island, as well as hundreds more from other factories.

The company's success ultimately led to the establishment of its own factory in Smethwick : the Soho Foundry , which was renamed James Watt & Co in 1848 and incorporated into a larger group in 1895. Today the area is partly used as a junkyard.

Money through money: the Soho Mint

As soon as the steam engine factory was out of trouble, Boulton looked around for new projects. An idea that had been unsuccessfully pursued 20 years earlier came back to his mind: The British economy demanded small-value coins, especially copper coins. Plans for its own mint began to mature in Boulton. Due to large overproduction, his copper mines were unprofitable and were about to close; The art of metalworking was at home in his Soho Manufactory , and for the heavy minting work there was a hydro-powered rolling mill for sheet metal production, steam-powered punching machines for the production of the coin blanks and steam machines for minting the coins. These areas only had to be merged and supplemented with a few new devices.

On a business trip to France, Boulton visited the Paris mint and met the engraver and designer Jean Pierre Droz . Droz had suggested some improvements but the royal mint rejected them. He wanted to enclose the coins in a strong frame during minting, which could be equipped with engraved patterns and lettering. This would have ensured that all coins had the same diameter and the same height, which made it almost impossible to falsify the coins by filing off precious metal at the edges. Boulton not only adopted the idea, but also the man. From 1787 Droz worked in Handsworth and began to design counterfeit-proof coins there.

The first customer for the new machines was the East India Company for their trade in Sumatra . In 1786, before the new machine house was completed, she ordered 100 tons of copper coins, which Boulton quickly delivered in the desired quality. Further orders followed immediately; The American colonies ordered copper money from Boulton, and France, Russia and Sierra Leone also had coins minted from him. Rich private individuals also wanted their own coins. For example, the successful cannon manufacturer John Wilkinson had his own coins produced in the Soho Mint in 1787 , which became a symbol of the changes in the balance of power brought about by the Industrial Revolution : for the first time in the history of English coinage, the portrait of an uncrowned head, an entrepreneur, was emblazoned on one Coin. Wilkinson's portrait was framed by his name and his profession: "John Wilkinson Iron Master".

In a new factory building built in 1788 for his Soho Mint , Boulton had steam engines with piston pistons installed instead of the slow and heavy manual embossing presses that had been customary up to that time and had to be operated by two strong men, which later only had to be monitored continuously by a twelve-year-old boy each ; the boys' only job was to turn the machines on or off. Boulton made these boys work in white uniforms, which were washed once a week to show that the boys had no physical labor to do. In addition, the boys' working hours were set at 10 hours a day - significantly less than the usual working hours of the era. Boulton not only demonstrated the efficiency of his new steam engines and their "child's play" operation, but was also able to realize Rousseau's idea of relieving children of work. With the additional automatic feeding of blanks and the mechanical ejection of the finished coins, the minting machines in this first series production produced between 50 and 120 coins per minute, depending on the size of the coins to be minted.

It was not until 1797 that the British Parliament gave its first order to mint copper coins. It was an order for 45 million pennies and two-pence coins, which became known as the cartwheel pennies . This ensured the long-term commercial success of this company.

Not only coins were minted in the Soho Mint . Artists quickly became aware of the possibilities offered by the new embossing machines. Before long, a flood of medals and commemorative coins for all sorts of events and people poured out onto the market, where they were sold extremely well. And again Boulton was the trigger for this fashion: He was able to convert further supplies of the otherwise difficult to sell copper from his mines into gold and at the same time employ the sculptors who designed the coins in a meaningful way when there were no other coin orders.

The Lunar Society - A think tank

→ Main article: Lunar Society

Boulton had grown up in an environment that not only instilled in him the desire for education, but encouraged, but failed to satisfy, his already existing curiosity. Boulton had gathered knowledge from all areas of the sciences of the time , largely through self-study , later also through his own experiments, which he then used in the form of improvements to his products. This enabled him to increase the quality of his goods to such an extent that he made a name for himself with his company not only in England and its colonies, but also on the European continent. In addition to his curiosity and keen business acumen, this encouraged another essential trait of Boulton's personality: his lust for fame. His friend James Watt would later even put this trait above Boulton's business acumen.

These three important traits of Boulton found in a chance encounter a supporter who was not only able to recognize them but also to shape them: Erasmus Darwin , highly educated physician and researcher from Lichfield . Darwin was the Robinson family doctor, which included Boulton's wives. The exact time of their first meeting is not known, but as early as 1762 their correspondence was so marked by friendly closeness and a shared urge to research that Darwin told the businessman Boulton, under the seal of secrecy, about his experiments to construct a steam-powered vehicle.

In those days the main features of today's science developed from the traditions of the past centuries with their strongly religiously shaped and limited ideas. In many parts of Europe wealthy and educated people met - that is to say: sometimes women and even children - for regular societies in which new observations, ideas and conclusions from the fields of the natural sciences and humanities were discussed. Occasionally there were even demonstrations; for example, public experiments on the newly discovered electricity, with all its spectacular sparks and effects, were a definite fad in those circles.

Boulton and Darwin also wanted to lay the foundation for such a circle, but it should serve less for amusing diversion than for joint, effective research and the search for new truths. After Boulton had put his Soho Manufactory into operation, the time seemed right for both of them to set up such a circle. Since they always wanted to meet at the full moon the next Monday in order to find their way home in the streets without lighting, they called their group The Lunar Society , with a wink to themselves Lunatics - "madmen".

The thought fell on fertile ground. Within a very short time, a circle of philosophers and scientists, entrepreneurs and artists from the area established themselves, who interacted, combined their possibilities and thus had a lasting influence on the natural sciences and humanities, but also on the English economy and its industrialization. The instrument maker (we would call him a precision mechanic today), John Whitehurst, designed a thermometer that could determine the temperatures of molten iron very precisely. Boulton financed the development and, conversely, benefited from improved production methods in both his craft products and the manufacture of steam engines.

But the humanities also shaped the discussions of the Lunatics ; especially the humanistic ideas of the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau were highly regarded in the group. They too shaped Boulton's ideas of what he, as the master of his workers and their families - as he saw himself: as mercantile princes - could do for their well-being. For example, Boulton's idea of introducing social security for his workers sprang from them. In the year of the Declaration of Human Rights, 1792, he introduced the Soho Insurance Society into his works. Like modern social systems, it worked according to the principle of solidarity: each worker paid one sixtieth of his wages into a joint fund, from which he received up to 80% of his wages as continued payment if he was sick or injured. In the event of death, his employee's family was insured for the same amount. Boulton voluntarily vouched with his private assets to prevent possible underfunding.

Boulton's refusal to hire cheap child labor also arose from Rousseau's ideas. In his opinion, children belong in a school. With this, Boulton had become a pioneer in children's rights, well before the introduction of compulsory schooling in England. However, the term child was seen a little differently at the time; Boulton employed twelve-year-old boys in his mint, albeit exclusively to turn the minting machines on and off, i.e. without physical exertion. For comparison: In England at the same time four-year-olds were being used for heavy physical work in mines; this was considered completely normal.

Boulton, who despite his heavy workload tried to be useful with his own experiments and considerations, was elected to the Royal Society on November 24, 1785. His election confirmation also includes three signatures from friends in the Lunar Society: Joseph Priestley , John Whitehurst, and Josiah Wedgwood . A particular scientific achievement was not emphasized. He had been a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh since 1784 .

Death and fame

Boulton died at the age of eighty on August 18, 1809 at his home in Birmingham. Like his partners and friends Watt and Murdoch, he was buried in the cemetery of St. Mary's Church in Handsworth (now Birmingham).

The company Boulton & Watt had already passed into the hands of the two sons of the founders in 1800, one year after the protective monopoly of the Watt steam engine had expired. Matthew Robinson Boulton and James Watt Jr. stopped the guided tours and slowly reduced the social achievements of the founders. The company was liquidated in 1910.

After the death of James Watts Jr. Soho Manufactory was closed in 1842 and largely demolished from 1848; the Boultons' house and some outbuildings have been preserved. The property Soho House is now a museum. Row houses were built on the site of the former manufactory, which also largely enclose the manor house.

An extensive archive of Boulton's letters and notes is in the Birmingham Central Library . It was established in 1910 when the Boulton & Watt company was liquidated and the city's business records were transferred. Boulton's private letters are also archived there. Letters and notebooks from this archive are now being systematically transferred into electronically readable form and made available on the Internet.

In Birmingham, the so-called moonstones also commemorate the co-founder of the Lunar Society; there is also a statue of him, Watt and Murdoch from 1956, Matthew Boulton College named after him, and Boulton Road , also all in Birmingham. There is also a Boulton Road in Smethwick . To this day, Boulton is considered one of the most important pioneers of the early industrial revolution, but he is overshadowed by the fame of his partner James Watt.

References and comments

- ↑ According to the Gregorian calendar , which was only introduced in Great Britain in 1752 , Boulton was born on September 14, 1728

- ^ L. Forrer: Biographical Dictionary of Medallists . Boulton, Matthew. tape I . Spink & Son Ltd, London 1904, p. 235 ff . (English).

- ↑ Jenny Uglow: The Lunar Men . 2nd Edition. Faber And Faber Ltd, London 2003, ISBN 0-571-21610-2 , pp. 25 .

- ↑ Jenny Uglow: The Lunar Men . 2nd Edition. Faber And Faber Ltd, London 2003, ISBN 0-571-21610-2 , pp. 62 .

- ↑ Boulton's notes suggest that he was looking for a cure for childbed fever shortly before Mary's death: Jenny Uglow: The Lunar Men . 2nd Edition. Faber And Faber Ltd, London 2003, ISBN 0-571-21610-2 , pp. 60 .

- ^ Letter to Lord Hawkesbury, April 17, 1790, Matthew Boulton Papers 237

- ↑ Michael Maurer: History of England . Philipp Reclam jun. GmbH & Co KG, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-010475-0 .

- ↑ !!!

- ↑ a b Joachim Fritz-Vannahme: “ Patent for power. Why the inventor James Watt needed the entrepreneur Matthew Boulton to become famous ”in: DIE ZEIT No. 25 of June 12, 2003, p. 24.

- ↑ Jonathan Hornblower, In: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2009.

- ^ B. Marsden: Watt's Perfect Engine: Steam and the Age of Invention. Columbia University Press, 2004.

- ^ Matthew Boulton and Medal Making. West Midlands History. University of Birmingham, accessed September 5, 2017 .

- ^ L. Forrer: Biographical Dictionary of Medallists . Watt & Co. (James Watt & Co.). tape VI . Spink & Son Ltd, London 1916, p. 391 ff .

- ^ Letter from Boulton to his agent Thomas Wilson about the successful minting order and the necessary organization.

- ↑ Short biography on the official website of the City of Birmingham

- ^ Entry on Boulton, Matthew (1728–1809) in the Archives of the Royal Society , London

- ^ Entry on Boulton; Matthew (1728–1809) in the Archives of the Royal Society , London

- ^ Biographical Index: Former RSE Fellows 1783–2002. Royal Society of Edinburgh, accessed October 10, 2019 .

- ↑ Brief description and photo of the statue of Boulton, Watt and Murdoch

literature

- Jenny Uglow : The Lunar Men . 2nd Edition. Faber And Faber, London 2003, ISBN 0-571-21610-2 .

- Robert E. Schofield: The Lunar Society of Birmingham: a social history of provincial science and industry in eighteenth-century England . Clarendon Press, Oxford 1963.

- Robert E. Schofield: Science, Technology and Economic Growth in the Eighteenth Century . Ed .: AE Musson. Methuen & Co, London 1972, ISBN 0-416-08000-6 , Chapter 5: The Industrial Orientation of Science in the Lunar Society of Birmingham.

- Golo Mann (Ed.): Propylaea World History . tape 8 : The nineteenth century . Propylaen Verlag, Berlin / Frankfurt am Main 1986, ISBN 3-549-05017-8 .

Web links

- Biography at RevolutionaryPlayers.org (English)

- Cornwall County Council: Transcribed business letters to and from Boulton between 1780 and 1793

- 200 year history of the Soho Mint

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Boulton, Matthew |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English engineer and entrepreneur |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 3, 1728 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Birmingham , Warwickshire |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 18, 1809 |

| Place of death | Birmingham |