Social projection

Social projection describes the process in which one's own attitudes , characteristics and behavioral tendencies are transferred to other people or groups of people.

Social projection in everyday life and in research

In everyday life we often have to assess people we don't yet know. We tend to regard our characteristics and behavioral tendencies as typical and therefore to generalize them to other people (compare induction ). The term “social projection” makes it clear that it is a transfer of one's own characteristics to a counterpart - that is, a “ projection ” of one's own characteristics that takes place in a social context.

The social projection is a heuristic for assessing strangers, i.e. a simplified strategy that often, but not always, leads to a correct judgment. In recent years, social projection has been increasingly scientifically studied in social psychology . This is a current field of research in psychology that deals, among other things, with the explanation of how social projection comes about and with the question of whether and when the application of social projection is helpful.

The procedure for social projection

Inductive reasoning

Social projection can be viewed as inductive reasoning . In general, inductive reasoning (induction) denotes a procedure in which the aim is to generalize observations of a sample to the general population ( population ) on which this sample is based. By looking at a sample, new information about the population should be obtained. This principle is also the basis of the social projection: Here it is observations of one's own characteristics and one's own behavior that are generalized to other people. If you and the stranger belong to the same population, you can consider your own characteristics as a small sample from the population of interest. Social projection, the transfer of one's own characteristics and attitudes to other people, can therefore be understood as a form of inductive reasoning.

Adequacy of social projection

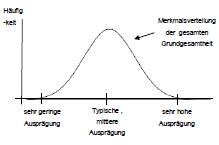

For many personality traits and attitudes that are considered in psychology, it is reasonable to assume that the distribution of the characteristics of all people on these variables corresponds to a normal distribution . This means that for these characteristics, the majority of people have a medium level and that only a few people have very high and very low levels. Therefore, the probability of encountering a person who has the same or a similar characteristic value as you are, the closer your own characteristic value is to the average characteristic value. Considered under statistical criteria, social projection is therefore appropriate and sensible if one's own expression on the relevant characteristic corresponds to the “medium expression” of the characteristic or is close to this expression.

Need for cognitive resources for social projection

Since there is a lot of information about oneself and one's own characteristics on various properties can in most cases be assessed quickly and without effort, social projection is initially a very simple process. Some scientific studies have investigated whether this process demands cognitive resources (such as attention and thinking skills). A scientific procedure ( paradigm , see also research design ), which is used here, implies that the study participants work on two tasks at the same time (use such a paradigm e.g. Krueger & Stanke, 2001). One of the two tasks is very difficult for some of the study participants and easier for the other part of the study participants. The other task involves assessing a stranger so that social projection becomes possible. It is then examined whether the difficulty of the first task influences the degree of social projection in the second task. This study structure is based on the assumption that people can only work on a limited number of tasks at the same time because their cognitive resources are limited. If only one task has to be worked on, all of the cognitive resources are available for this. But if several tasks have to be processed at the same time, it is assumed that the resources have to be divided. It is also assumed that a task requires more cognitive resources the more difficult it is. However, there are also tasks that require little or no cognitive resources, such as riding a bike: once you've learned it, you don't need (almost) any concentration to be able to ride a bike. The study structure described examines whether social projection belongs to these automatic processes or whether it requires cognitive resources. The studies mentioned show that social projection takes place regardless of the difficulty of the additional task. This suggests that social projection requires little or no cognitive resources. These study results clarify the relevance of social projection by showing that social projection takes place automatically and is also used when the focus is on another task or when we are busy with something else. Other studies show that social projection cannot be deliberately reduced, but takes place even when the study participants are asked not to use their own characteristics as a basis for assessing other people in the course of the study. Taken together, these study results raise the question of what causes or facilitates social projection. The question of conditions and situations that trigger social projection needs to be examined more closely in future research.

Social projection in groups

The results of previous research indicate that social projection often occurs - (partially) without being consciously used - and is therefore important and very robust. However, there are conditions under which the strength of social projection changes. One of these conditions is the division of people into groups.

Social projection onto ingroups and outgroups

If one conducts a study in which groups are formed before the assessment of strangers ( social categorization ), one finds a large difference in the extent of the social projection in relation to the “ ingroup ” - that is, the group to which the study participant belongs - and the “ outgroup ” to which the study participant does not belong: The social projection of one's own characteristics on outgroups is much lower than on ingroups. This means that people ascribe their own characteristics, attitudes and behavioral tendencies more to members of their ingroup than to members of an outgroup. As a result, self-descriptions predict ingroup assessments better than outgroup assessments.

The classification of groups can either be based on characteristics such as gender or nationality, or on the basis of less obvious and even on the basis of little known and relevant characteristics (for example by using a minimal group paradigm ). The effect of the varying degrees of social projection on ingroups and outgroups can be found in every type of social categorization.

Social projection and evaluation of a group

When examining social groups, numerous studies have shown that people rate ingroups more positively than outgroups (Mullen, Brown & Smith, 1992). According to Henri Tajfel, this tendency in the evaluations of groups is called ingroup bias (“ ingroup error”). If one explains social projection by inductive reasoning, then the ingroup preference is understood as a direct result of differences in the social projection of the (for most people) positive self-image onto the ingroup and the outgroup.

Differentiation of social projection from self-stereotyping

When a person assesses himself and a group of people very similarly, it is not possible to say for sure that social projection has taken place. Although a high correlation can be explained between self and group assessments by social projection - but there are also the opposite approach that is self-stereotyping ( self-stereotyping ) calls. Self-stereotyping means that a person applies assumptions - so-called stereotypes - and knowledge about an ingroup (e.g. about "all Germans") to themselves. If the stereotypes are positive, this can serve to increase one's self-worth . Social projection - i.e. the transfer of knowledge about oneself to a group - and self-stereotyping - i.e. the transfer of knowledge about a group to oneself - are not mutually exclusive. In the future it will have to be investigated in more detail whether social projection and self-stereotyping occur together or in different situations.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Krueger, JI (2007). From social projection to social behavior. European review of social psychology, 18, 1-35.

- ^ JI Krueger: The projective perception of the social world: A building block of social comparison processes. In: J. Suls, L. Wheeler (Eds.): Handbook of social comparison: Theory and research. Plenum / Kluwer, New York 2000, pp. 323-351 (English).

- ^ Hoch, SJ (1987). Perceived consensus and predictive accuracy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 221-234.

- ↑ Krueger, JI & Clement, RW (1996). Inferring category characteristics from sample characteristics: Inductive reasoning and social projection. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 125, 52-68.

- ↑ Clement, RW & Krueger, JI (2000). The primacy of self-referent information in perceptions of social consensus. British Journal of Social Psychology, 39, 279-299.

- ↑ Krueger, JI & Stanke, D. (2001). The role of self-referent and other-referent knowledge in perceptions of group characteristics. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 878-888.

- ↑ Krueger, JI & Stanke, D. (2001). The role of self-referent and other-referent knowledge in perceptions of group characteristics. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 878-888.

- ↑ Clement, RW & Krueger, J. (2002). Social categorization moderate social projection. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 219-231.

- ^ A b Henri Tajfel , Michael Billig, RP Bundy, C. Flament: Social categorization and intergroup behavior. In: European Journal of Social Psychology. Volume 1, No. 2, April 1971, pp. 149-178 (English; doi: 10.1002 / ejsp.2420010202 ).

- ↑ Otten, S. & Wentura, D. (1999). About the impact of automaticity in the Minimal Group Paradigm: Evidence from affective priming tasks. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29, 1049-1071.

- ↑ Clement, RW & Krueger, J. (2002). Social categorization moderate social projection. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 219-231.

- ↑ Alicke, MD & Govorun, O. (2005). The better-than-average effect. In MD Alicke, D. Dunning & JI Krueger (eds.), The self in social judgment (pp. 85-106). New York: Psychology Press.

- ↑ Krueger, JI (2007). From social projection to social behavior. European review of social psychology, 18, 1-35.

- ↑ Turner, JC, Hogg, MA, Oakes, PJ, Reicher, SD & Wetherell, M. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- ↑ Burkley, M. & Blanton, H. (2005). When am I my group? Self-enhancement versus self-justification accounts of perceived prototypicality. Social Justice Research, 18, 445-463.