Women's Freedom League

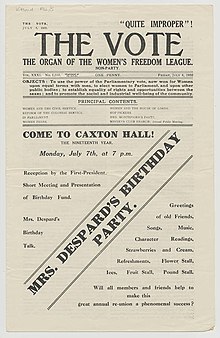

The Women's Freedom League (WFL) was an organization in the UK that campaigned for women's suffrage and women's equality . It split from the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1907 , when Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Christabel undemocratically placed the WSPU under their sole control. A separate newspaper, The Vote , ensured communication with the public and the dissemination of the WFL's ideas and information.

history

The group was founded in 1907 by seventy-seven members of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), including Teresa Billington-Greig , Charlotte Despard , Alice Schofield , Edith How-Martyn, and Margaret Nevinson . They disagreed with Christabel Pankhurst's announcement that the WSPU's annual conference would be canceled and that future decisions would be made by a committee that would appoint it.

The new league rejected violence and instead wanted to use non-violent forms of protest ; this included refusal to pay taxes , not filling out census forms, organizing demonstrations and also the self-self-chaining of objects in the Palace of Westminster . The WFL grew to over 4,000 members and published the weekly newspaper The Vote from 1909 to 1933 . Dr. Elizabeth Knight (doctor) took care of the funding of the Women's Freedom League. In 1912 she took over the office of Treasurer from Constance Tite and improved the financial situation of the WFL. Before being appointed, it sometimes had to reach out to its members and ask for loans. Knight launched a fundraising program for the WFL. The large donation from an “anonymous” person also helped improve the finances; it is believed that it was Knight himself.

In 1912 Nina Boyle became the head of the political and militant department of the WFL. She published many articles in the WFL newspaper, The Vote . Boyle started a campaign for women to give them the opportunity to become auxiliary cops. This campaign coincided in 1914 with the outbreak of World War I and the call for support for the war effort Boyle had wanted women and men. When the application was officially denied, Boyle and Margaret Damer Dawson , a wealthy philanthropist and activist for women's rights, founded the first voluntary women's police force - Women Police Volunteers (WPV).

The League continued its pacifism during World War I and supported the Women's Peace Council . When the war broke out, they had suspended their campaigns and volunteered.

In the British General Election in 1918 Despard, How-Martyn and Emily Frost Phipps ran unsuccessfully in London as independent anti-war candidates for women's rights. They celebrated the achievement of women's suffrage and refocused their activities on the problems of gender equality, equal pay and the equality of morals between men and women.

The WFL dwindled in membership, but under the leadership of Marian Reeves , they continued to organize annual birthday parties for Despard and to run the Minerva Club in Brunswick Square. After Reeves' death, the WFL voted to disband in 1961.

The Vote Newspaper and Growth in the Women's Freedom League

After the Women's Freedom League was founded in 1907, it continued to grow rapidly across the UK. The league consisted of sixty branches and had nearly four thousand members. The league started its own newspaper called The Vote . Members of the league included women writers who contributed a lot to the production of the newspaper. The Vote became the main means of communication with the public, informing the public about campaigns, protests and events. This newspaper also helped spread ideas about World War I by enabling the Women's Freedom League to take a stand against the war. Members of the league refused to participate in the campaigns led by the British Army. Members were upset when their campaign for women's suffrage came to a halt during the war.

Protests and events

The main goal of the league was to criticize, fight against and reform the government. The league hosted protests advocating pacifism during World War I. Not only did the league oppose war, but it also used peaceful forms of protest such as refusing to fill out census forms and not pay taxes. Members chained themselves to various objects in parliament in 1908 and 1909 to protest against the government. On October 28, 1908, three members of the Women's Freedom League, Muriel Matters , Violet Tillard and Helen Fox, displayed a banner in the House of Commons. The women also chained themselves to the bars of a window. Law enforcement officers had to remove the grille while it was still attached until they could file down the locks they attached to the window. This protest became known as the "Grille Incident".

Two members of the league, Alice Chapin and Alison Neilans , attacked polling stations during the Bermondsey by-election in 1909 and smashed bottles of corrosive liquid over ballot boxes to destroy votes. An electoral officer, George Thornley, was blinded in one eye in one of these attacks, and a Liberal representative was badly burned to the neck. The count was delayed as the ballot papers had to be carefully checked. 83 ballot papers were damaged but legible, but two ballot papers could no longer be deciphered. They were later sentenced to three months each in Holloway Prison .

The "brown women" were named after the brown coats they wore when hiking. Agnes Brown (by chance), Isabel Cowe and four other women left Edinburgh to run for London. They wore white scarves and green hats, and on their travels collected signatures for a petition for women's rights. The hikers had to walk fifteen miles a day and attend meetings every day, so it took them five weeks to reach London.

archive

The Archives of the Women's Freedom League are located in the Women's Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science library .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Alice Schofield. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ^ A New woman suffrage weekly paper has just appeared in London, entitled The Vote. In: The Publishers Weekly . 76th edition. 1909, p. 1922 .

- ↑ CLAIRE LOUISE EUSTANCE: WOMEN'S FREEDOM LEAGUE. In: Whiterose.ac.uk (York Uni). 1993, accessed January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ RM Douglas: Feminist free corps: the British voluntary policewomen, 1914-1940 . Great Britain ? 1999, p. 10 .

- ↑ The Times (Ed.): The Times . August 15, 1914, p. 9 .

- ^ Women Police Service. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ Reeves, Marian. In: oxforddnb.com. Dictionary of National Biography, accessed January 19, 2019 .

- ^ Women's Freedom League. In: spartacus-educational.com. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ^ Women's Freedom League - Women of Tunbridge Wells . Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ Women's Freedom League. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ↑ The Times (Ed.): The Times . October 29, 1909 (English, thetimes.co.uk ).

- ^ Centenary of Bermondsey suffragette protest. October 28, 2009, accessed January 19, 2019 .

- ^ Eleanor Gordon: Brown, Agnes Henderson (1866-1943) . Ed .: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2004 (English).

- ↑ Agnes Henderson Brown and Jessie Brown. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ^ Records of the Women's Freedom League. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .