Interest parity theory

The interest parity theory is a widely used economic model that goes back to John Maynard Keynes . First, it provides an explanation for investor behavior: Investors invest where the highest return can be achieved. Building on this, the interest parity theory is secondly a short-term explanatory model for exchange rate movements used in foreign trade . It explains exchange rate movements solely with the return interest of capital investors. A distinction can be made between the covered and the uncovered form of interest parity.

Definition of interest parity

Interest parity (parity from the Latin par “equal”) implies that the domestic rate of return is equal to the foreign rate of return. The domestic rate of return is the nominal domestic interest rate i , the foreign return by the nominal, foreign interest rate i * plus expected exchange rate ( defined) .

"Interest parity is the relationship between the national money market and the international money market, whereby the exchange rate is adjusted so that the difference between the domestic and foreign interest rates corresponds to the difference between the effective and the expected exchange rate".

“The currency market is in equilibrium when deposits offer the same expected return in all currencies. This equality of the expected returns on deposits in any two currencies, measured in the same currency, is known as interest parity ”.

"Interest parity applies the law of the single price to fixed-income and homogeneous financial stocks, which means that assets with comparable risk regardless of the country in which they are traded have the same expected return."

Requirements for achieving interest parity

In order for there to be interest parity (permanently), total capital mobility and the perfect substitutability of securities are required . With perfect capital mobility, the capital can be transferred to the desired form of investment without restriction at any time, while the imperfect capital mobility delays the reaction of the capital markets.

Complete substitutability of the investments only applies to investors who are risk-neutral, whereby the financial assets are only compared on the basis of the expected returns. If investors demand an additional risk premium or an additional hedging transaction in the sense of swaps for the exchange rate risk , the investments are not perfect substitutes.

Furthermore, interest parity requires the existence of currency market efficiency . This means that the exchange rate always reflects all relevant information available for price formation. There are no transaction costs, there are no trade barriers and all market participants must have identical expectations with regard to exchange rate developments.

In the case of flexible exchange rates, an additional variable, the uncertainty of exchange rate changes, must be included in the calculation, which influence the return on financial investments abroad during the investment period.

The condition of interest parity

The condition of interest parity exists when the difference between the domestic and foreign interest rate corresponds to the difference between the effective and the expected exchange rate.

This leads to the following conclusion: the higher the rate of change in a country's exchange rate, that is, the faster the country's currency depreciates, the higher the nominal interest rate of that country must be.

The existence of the condition of interest parity results in an equality of return of domestic and foreign investments. The investor is thus indifferent to an investment in Germany and an investment abroad.

Basic idea

The central assumption of the interest parity theory is that investors invest where they can generate the greatest return. If investors act accordingly, the currency of the more attractive investment location is always revalued in a two-country case. The interest parity theory in its basic structure only considers the interest rate and the exchange rate expectations as return variables . If one differentiates between Germany and abroad as a possible investment location, the following applies:

Domestic rate of return

The domestic return corresponds to the domestic interest , i.e.

Foreign return

The return abroad is accordingly also significantly influenced by the foreign interest rate . Moreover, it is for a domestic investor but also important, as the exchange rate between domestic and foreign currencies to e developed in the investment period; For the domestic investor, an investment abroad would make sense in terms of returns if the foreign currency is appreciated as long as the investor has invested abroad. Conversely, the expectation of a future devaluation of the foreign currency will reduce the investor's interest in a foreign investment.

The interest parity theory models this relationship via the introduction of an expected exchange rate ( ). This variable represents the investor's expectations about the level of the exchange rate at the end of the investment period - that is, the rate that the investor expects as the exchange rate before making the investment. Using an approximate formula, the model determines an investor's income from expected exchange rate movements:

Note: The representation used here is based on the quantity notation of the exchange rate.

The formula for income from changes in exchange rates can be interpreted as follows: If the current exchange rate (back exchange rate) and the expected exchange rate match at the time of investment , the investor will not receive any additional exchange rate income , as expected, nor will the investor incur any additional costs from the exchange rate change.

If, on the other hand, the expected exchange rate is below the current exchange rate, this means nothing other than the expectation of a devaluation of the domestic currency (example: the current exchange rate between dollar and euro is the expected future rate - then the investor will receive exchange rate income from an investment in the USA Since he receives 1.20 US dollars for one euro exchanged in. If he exchanges this 1.20 US dollars back into euros at the end of the investment period, he receives more than the original euro, since it is now 1.10 US dollars Dollar equals one euro). If there is an expectation of appreciation in terms of the foreign currency, investing abroad is worthwhile.

The opposite applies if the expected exchange rate is greater than the current one. The then existing expectation of devaluation leads to costs for the investor (example: The current exchange rate is US dollar per euro that is expected in the future . The investor therefore exchanges one euro for 1.20 US dollars at the beginning. However, at the end of the investment period he would need 1.30 US dollars to get the original euro back - so it makes a loss).

The total return of a foreign investment is then calculated according to the interest parity theory from the interest income and the expected exchange rate income and is accordingly

- .

Investor behavior due to a lack of interest parity

If the return in Germany is greater than that abroad ( ), the investor will invest his capital in Germany. Conversely, he will prefer a foreign investment if its return is greater than that of a domestic investment ( ). If both returns are the same ( ), the investor is indifferent.

Changes in exchange rates due to a lack of interest parity

As already mentioned, an unequal return at home and abroad implies a certain exchange rate development. If the return abroad is higher than in Germany, the resulting investment abroad will lead to an appreciation of the foreign currency because the foreign currency has to be requested in order to invest money abroad. Conversely, a higher domestic return will lead to an appreciation of the domestic currency, as capital is withdrawn from abroad and invested domestically. According to the interest parity theory, exchange rate movements can thus be explained on the basis of investors' pursuit of returns.

Interest parity as an equilibrium solution

However, the assumed exchange rate changes as a result of the investment decision have repercussions on the investment decision itself (example: An investor realizes that the return on an investment in the USA is higher than those in Europe due to an appreciation expectation with respect to the US dollar [ and ] invest in the USA, which is why the US dollar appreciates. However, this appreciation reduces the subsequent appreciation expectation for subsequent investors, since the US dollar has already appreciated before they invested [ and ]) - the attractiveness of an investment location thus reduces its future attractiveness . The process of matching returns only comes to an end when the returns on both investments are identical.

As long as one of the two systems is more profitable, the investment there leads to an appreciation of the local currency and thus to a decrease in the return. According to the interest parity theory must therefore apply . Or in other words:

- .

According to the theory, this so-called interest parity condition must be fulfilled at all times, since any deviation from parity would result in immediate arbitrage behavior.

Interest parity using the example

First, some central model assumptions are set up for an understandable explanation or illustration. The model is broken down into two countries with two different currency systems (Germany € / USA $). It is assumed that the financial markets of both countries are open and that there are no restrictions . Furthermore, investors can initially only trade securities with a term of one year. Let us now consider the calculation of a German investor who decides whether to invest in a German security with a one-year term or an American one with the same term. It must be checked which system promises a higher return.

be the nominal interest rate for German securities. The investor receives a return of euros for every euro. (This is visualized in the following illustration by the upper arrow pointing to the right).

| Year ( ) | → | Year ( ) | |

| German bonds: | 1 € | → | |

| US bonds: | 1 € | → | |

| ↓ | ↑ | ||

| → |

Now let's compare the return on an American security. Before the German investor can invest in American securities, he must first buy American dollars . If the nominal exchange rate is between the euro and the dollar, then one earns dollar for every euro . (This is visualized in Figure 1 by the down arrow)

indicates the nominal interest rate for American securities. You will therefore receive dollars at the end of the term (after one year) . (This can be seen in Figure 2.2.1 at the bottom arrow pointing to the right)

At the end of the year, the investor has to exchange his dollars for euros again. At the end of the term, the investor expects an exchange rate that can be explained by the expected value of the exchange rate in the form of . This implies that at the end of the year the investor will get euros back for every euro he has invested . (This is shown in Figure 2.2.1 by the arrow pointing upwards to the right)

The key message of this consideration is obvious - if one compares the security returns of the two countries with each other, one comes to the conclusion that not only the differences in returns are relevant for the decision, but also the exchange rate expectations that the investor has at the end of the security's term. Based on these considerations, it is assumed that the investor is only interested in the highest expected return. This investor will then hold the security in their portfolio , which promises the highest expected return . This would mean that German and American stocks achieve exactly the same expected return; nobody would be willing to hold a paper with a lower yield. The following arbitrage condition must therefore be met:

or

In this specific case, the arbitrage effect means that the yields of both countries converge . In this case, one speaks of interest parity (parity from the Latin par “equal”) or uncovered interest parity.

If the return in Germany is greater than that abroad , the investor will invest his capital in Germany. Conversely, he will prefer a foreign investment if its return is greater than that of a domestic investment . If both returns are the same , the investor is indifferent .

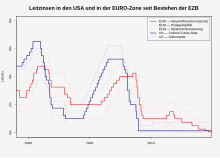

As already mentioned, an unequal return at home and abroad implies a certain exchange rate development . If the return abroad is higher than in Germany, the resulting investment abroad will lead to an appreciation of the foreign currency because the foreign currency has to be requested in order to invest money abroad. Conversely, a higher domestic return will lead to an appreciation of the domestic currency, as capital is withdrawn from abroad and invested domestically. According to the interest parity theory, exchange rate movements can thus be explained on the basis of investors' pursuit of returns . This would mean, for example, that an investor who holds American securities invests in German securities if this investment produces a higher return. Consequently, this investor will exchange dollars for euros, thus increasing the demand for euros and the supply of dollars. As a result, the price (exchange rate) for euros rises and the price (exchange rate) for dollars falls. The reason for this is the lack of interest parity. If you look at both of the adjacent figures, you can see the dependency of the dollar to euro exchange rate on a current example. The key interest rates fall over time and at the same time the dollar is devalued against the euro.

Uncovered interest parity

Every for-profit investor is interested in the securities that generate the highest returns and will keep them in their portfolio.

This in turn would mean that German and American securities would have to generate the same return in order to be attractive to investors.

If you rearrange the above equation under the assumption of small returns, the approximate result is:

This equation is also known as uncovered interest parity.

The quotient indicates the percentage expectation of an exchange rate change. So if market participants expect, for example, a two percent devaluation of the domestic currency over the given investment period, they will only be willing to invest in the domestic asset if the domestic interest rate is exactly two percentage points higher than the foreign interest rate.

In the case of uncovered interest parity, it is assumed that the market participants bear the uncertainty of the currency exchange when investing abroad. You accept the exchange rate risk, which is not covered. Due to the exchange rate risk, this is based on a speculative transaction.

Covered interest parity

If the investor does not want to take on price risk , he can conclude a forward transaction at the same time.

This forward transaction takes place on the foreign exchange futures market, which exists alongside the "actual" foreign exchange market ( foreign exchange spot market ). The objects of trading on these futures markets are financial derivatives . With such a forward transaction, the rate at which the foreign exchange is to be transferred or exchanged again in one year is set at the beginning of the year. This type of hedging transaction is also known as a swap .

If you now replace the expected exchange rate in the equation for the uncovered interest parity with the forward rate , you get the equation for the covered interest parity.

With the covered interest parity, an exchange rate risk is avoided. As a result, it represents a pure arbitrage equilibrium. If the covered interest parity did not apply, the economic subjects would have the possibility of currency arbitrage , that is, they could use international interest rate differentials to their advantage to generate profits.

Example of covered interest parity

In the case of interest parity or uncovered interest parity, three factors are used as a basis (exchange rate, return on the investment, expected value of the return), which are decisive for the decision whether to invest in Germany or abroad. Here, some important factors are neglected. For example, there are transaction costs associated with investing in foreign securities ; H. dollars must be bought in order to invest in the American securities market, and when the term expires, the dollar income must be converted back into euros. Another example is the foreign currency risk , since the exchange rate at the end of the term is an uncertain variable. Market participants can also be influenced by liquidity factors. In order to put a stop to the uncertainty of the factors, the investor uses the secure function of the futures contract with the covered interest parity . Future exchange rates can be hedged via the futures market . This offers investors the opportunity not only to expect future exchange rates under uncertainty, but to secure them through futures market transactions. This would mean that an investor who buys with euro dollar deposits wants to know with certainty how many euros this dollar deposit will be worth after a year. He excludes this uncertainty by simultaneously selling the principal plus interest at the same time as buying a dollar deposit for one year in exchange for euros. He has thus "covered" his purchase, which means that he has hedged against unexpected depreciation of the euro. Such hedging transactions are known as swaps .

An example is provided to illustrate the importance of this condition and the reasons for its inevitable validity. The twelve-month forward rate of the euro in dollars = $ 1.113 per euro. At the same time, let the spot exchange rate = $ 1.05 per euro, = 0.10 and = 0.04. The dollar return on a dollar deposit is therefore 0.10 or 10% annually. How high is the return on a covered euro deposit? A deposit over € 1 costs $ 1.05 today and is worth € 1.04 after a year. If you sell € 1.04 today at a forward exchange rate of $ 1.113 per euro, one year later the dollar value of your investment will be ($ 1.113 per euro) x (€ 1.04) = 1.158. The return on the covered purchase of a euro deposit is therefore (1.158 - 1.05) / 1.05 = 0.103. This 10.3% annual return exceeds the 10% return on dollar deposits, so there is no covered interest parity. In this situation nobody would be willing to hold dollar deposits, everyone would prefer euro deposits. As a result, the covered return on the euro deposit can be expressed in the following form:

- Equation 3.1

This corresponds roughly

- Equation 3.2

when the product is a small value. The covered interest parity can therefore be expressed in the following form:

- Equation 3.3

The size

- Equation 3.4

is referred to as the forward premium (report) of the euro against the dollar (or as the forward discount or deport of the dollar against the euro). Based on this terminology, we can describe covered interest parity as follows: "The interest rate on dollar deposits is equal to the interest rate on euro deposits plus the forward premium of the euro against the dollar (or the forward discount of the dollar against the euro)". It should be remembered that both uncovered and covered interest parity are only met if the twelve-month forward rate is the same as the spot rate. But the crucial difference between uncovered and covered interest parity lies in the exchange rate risk. With uncovered interest parity, in contrast to covered interest parity, there is an exchange rate risk.

Empirical relevance and possible uses of interest parity

In the past, empirical studies have shown that the condition of covered interest parity can be regarded as fulfilled. However, this validity has lost its importance since the 2008 financial crisis. Since the financial crisis, there have been some significant deviations from the covered interest parity for many G10 currencies. Science explains these deviations by one-sided hedging demands combined with increased regulatory costs for banks and liquidity premiums.

The condition of uncovered interest parity has always been deemed not to have been met. Inefficiencies in the currency markets and non-risk-neutral behavior on the part of market participants are seen as the reasons why the condition of uncovered interest parity is not met.

The interest parity condition is often used as an integral part of modern exchange rate theories. Both the monetarist exchange rate model and the Dornbusch model of excessive exchange rates are based on the assumption of uncovered interest parity. Interest parity can also be applied to empirical exchange rate issues.

In addition, the interest parity theory is the subject of extensive research. It was often empirically verified due to the simple data acquisition. Surprisingly, however, the theory is mostly refuted empirically. This is usually attributed to the fact that other influencing factors than interest rates and exchange rate expectations also influence the investment decision or that important prerequisites for the validity of the theory (e.g. the existence of perfect capital markets) do not apply.

In a study by the Deutsche Bundesbank, for example, a so-called currency carry trade (taking out a loan in a currency with low interest rates and simultaneously investing in a currency with high interest rates) is highly profitable; if interest parity is valid, the high-interest currency should actually depreciate over time - and thus reduce the interest rate advantage.

Nevertheless, there is a scientific consensus that a strong deviation from the interest rate parity is hardly possible due to the arbitrage business that then begins.

Individual evidence

- ^ Woll, Artur (2002), Wirtschaftslexikon, Munich, Vienna: Oldenbourg Verlag

- ^ Krugman, Paul R .; Obstfeld, Maurice (2006), International Economics, Pearson

- ↑ Herrmann, Sabine; Jochem, Axel (2003), The International Integration of Foreign Exchange Markets in the Central and Eastern European Accession Countries: Speculative Efficiency, Transaction Costs and Exchange Rate Premiums, Discussion Paper: Economic Research Center of the Deutsche Bundesbank

- ^ Claassen (1980), Fundamentals of the macroeconomic theory, Verlag Vahlen

- ↑ Barro, Robert; Grilli, Vittorio (1996), Macroeconomics, Munich, Vienna: Oldenbourg Verlag

- ^ Blanchard, Oliver, Illing, Gerhard (2006) Macroeconomics, Munich, Pearson Verlag, p. 531

- ↑ Blanchard, Oliver / Illing, Gerhard: Makroökonomie, 4th updated and expanded edition, Pearson Studium, Munich 2006, p. 531.

- ↑ Blanchard, Oliver / Illing, Gerhard: Makroökonomie, 4th updated and expanded edition, Pearson Studium, Munich 2006, p. 531.

- ↑ Dornbusch, Rüdiger / Fischer, Stanley / Startz, Richard: Makroökonomie, 8th edition, R. Oldenbourg, Munich 2003, pp. 534–535.

- ↑ Blanchard, Oliver / Illing, Gerhard: Makroökonomie, 4th updated and expanded edition, Pearson Studium, Munich 2006, p. 531.

- ↑ Cf. Blanchard, Oliver / Illing, Gerhard: Makroökonomie, 4th updated and expanded edition, Pearson Studium, Munich, 2006, S532

- ↑ Blanchard, Oliver, Illing, Gerhard (2009) Makroökonomie, Munich, Pearson Verlag, p. 531

- ↑ Baßeler, Ulrich; Heinrich, Jürgen; Utecht, Burkhard (2002), Basics and Problems

- ^ Blanchard, Oliver, Illing, Gerhard (2006) Macroeconomics, Munich, Pearson Verlag, p. 531

- ↑ Cf. Glasfetter, Werner: Foreign Trade Policy, A Problem-Oriented Introduction, 3. completely revised. and extended edition, Munich, 1998, pp. 433-434

literature

- Keith Cuthbertson, Dirk Nitzsche: Quantitative Financial Economics - Stocks, Bonds and Foreign Exchange . 2nd edition. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. January 2005. ISBN 978-0-470-09171-5 .

- German Bundesbank. Monthly report November 1993. Development and determinants of the external value of the D-Mark, p. 41

- German Bundesbank. Monthly report July 2005. Exchange rate and interest rate differential: recent developments since the introduction of the euro. P. 31. From: http://www.bundesbank.de

- Barro, Robert; Grilli, Vittorio (1996), Macroeconomics: European Perspective , Munich, Vienna: Oldenbourg Verlag.

- Baßeler, Ulrich; Heinrich, Jürgen; Utecht, Burkhard (2002), Fundamentals and Problems of Economics , Stuttgart: Schäffer - Pöschel Verlag.

- Beck, Bernhard (2004), Understanding Economics , Zurich: vdf Hochschulverlag AG at ETH Zurich.

- Blanchard, Olivier; Illing, Gerhard (2006), Macroeconomics , Munich: Pearson Verlag.

- Cezanne, Wolfgang (2002), General Economics , Munich, Vienna: Oldenbourg Verlag.

- Claassen, Emil-Maria (1980), Fundamentals of the macroeconomic theory , Munich: Verlag Vahlen.

- Engelkamp, Paul; Sell, Friedrich (2002), Introduction to Economics , Berlin: Springer Verlag.

- Heine, Michael (2000), Economics: paradigm-oriented introduction to economics , Munich, Vienna; Oldenbourg Publishing House.

- Herrmann, Sabine; Jochem, Axel (2003), The International Integration of Foreign Exchange Markets in the Central and Eastern European Accession Countries: Speculative Efficiency, Transaction Costs and Exchange Rate Premiums , Discussion Paper: Economic Research Center of the Deutsche Bundesbank.

- Krugman, Paul R .; Obstfeld, Maurice (2006), International Economics , Pearson Verlag.

- Woll, Artur (2002), Wirtschaftslexikon , Munich, Vienna: Oldenbourg Verlag.