Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 165.134.194.78 to last version by Wrad |

→Themes: adding back the theme section bit |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

The boar scene has a lot more detail. Boars at the time were much more difficult to hunt than deer. To take one on with nothing but a sword was akin to challenging a knight to single combat. In the hunting sequence, the boar at first flees, but is eventually cornered in a ravine. He turns to face Bercilak with his back to the ravine, prepared to fight. Bercilak dismounts, and in the ensuing fight, manages to kill the boar. He removes its head is and sets it on high. In the seduction scene, Bercilak's wife, like the boar, is a bit more forward, insisting that she knows that Gawain has quite a romantic reputation, and that she deserves a taste of it. Gawain, however, is successful in parrying her attacks, saying that surely she knows more than he about love already. Both the boar and the seduction scene can be seen as depictions of a moral victory.<ref name = Burnley/> |

The boar scene has a lot more detail. Boars at the time were much more difficult to hunt than deer. To take one on with nothing but a sword was akin to challenging a knight to single combat. In the hunting sequence, the boar at first flees, but is eventually cornered in a ravine. He turns to face Bercilak with his back to the ravine, prepared to fight. Bercilak dismounts, and in the ensuing fight, manages to kill the boar. He removes its head is and sets it on high. In the seduction scene, Bercilak's wife, like the boar, is a bit more forward, insisting that she knows that Gawain has quite a romantic reputation, and that she deserves a taste of it. Gawain, however, is successful in parrying her attacks, saying that surely she knows more than he about love already. Both the boar and the seduction scene can be seen as depictions of a moral victory.<ref name = Burnley/> |

||

===Nature vs. chivalry=== |

|||

William F. Woods argues for nature’s influence on the story and characters of the poem. Woods presents nature as a major theme in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight—representing a form of chaotic order inherent through out the poem. The green horse and rider that first invade the Arthur’s peaceful halls can be seen as icons representing the disturbance of nature and such chaos (213). Nature itself is presented in the poem as rough and indifferent, ever threatening the order of men and courtly life (215). As the poem progresses, one can see nature come to invade and disrupt such order in the major events (symbolically or through the elemental inner nature of man)—first with the disruption of the Green Knight (213), then later when Gawain must fight off the temptations of Bertilak’s wife (220), and finally when Gawain breaks his vow to Bertilak and the Green Knight by choosing to keep the green girdle and choosing his personal survival rather than virtue (222). Nature is an underlying force that seems to be a part of man that keeps him forever imperfect (in a chivalric sense), as represented by the sin stained girdle (222). |

|||

While Woods claims that nature provides a stronger order in the poem (a different kind of perfection), Richard Hamilton Green believes that the poet aims at the quest for chivalric perfection over nature. According to Green, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight “embodies the chivalric ideals of the English ruling class (121).” Green too recognizes nature as another force in the poem (with the Green Knight representing this “world of mystery (125)”), but rather than present it as an inevitable ruler over man he asserts that the author creates a “dark world of potential failure” and warns “of powers of evil which may corrupt even the most virtuous men and institutions (123).” There is a subtle difference between authors—while Woods claims that the Pearl Poet removes responsibility from Gawain’s actions through nature, Green argues that chivalry is the greater and more virtuous order presented by the poet. Gawain, himself, is to represent the heroic ideal in the poem yet still has his shortcomings—the poet does not “transform vice into virtue for the sake of the general comfort (129).” Gawain truly is imperfect, and it is through his lesson of humility that he finds redemption (129). |

|||

===Games=== |

===Games=== |

||

Revision as of 04:32, 2 October 2007

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a late 14th century alliterative chivalric romance outlining an adventure of Sir Gawain, a knight of King Arthur's Round Table. The poem survives on a single manuscript along with three pieces of a religious character, all written by the "Pearl poet" or "Gawain poet," an unknown author. The four narrative poems are written in a North West Midland dialect of Middle English.[1] The manuscript is currently in the British Library.[2]

In the story, Sir Gawain, a knight of King Arthur's Round Table, accepts a challenge from a mysterious warrior who is completely green. The "Green Knight" offers to allow anyone to strike him with his axe if he will take a return blow in a year and a day. Gawain accepts the challenge, and beheads him in one blow, only to have the Knight stand up, pick up his head, and remind Gawain to meet him at the appointed time. Gawain's struggle to meet the appointment, and the adventures involved, cause this work to be classified as an Arthurian tale involving themes of chivalry and loyalty.

Alongside its advanced plot and rich language, the poem's chief interest in the critical and historical worlds is in the symbolism and themes which place it in its historical context. Everything, from the Green Knight, to the beheading game, to the girdle given Gawain as a protection from the axe, is richly symbolic and steeped in Celtic, Germanic, and other historical cultures and folklores. As a result, critics often compare Gawain to similar, older works, such as the Irish tales of Cúchulainn, in order to find possible meanings and contexts for the symbolism and themes within the poem. A later poem, The Greene Knight, tells essentially the same story as Sir Gawain, though the relationship between them is not clear.

Plot synopsis

The story begins in King Arthur's court at Camelot as the court is feasting and exchanging gifts. A gigantic Green Knight armed with an axe enters the hall and proposes a game. He asks that someone in the court take the axe and strike a single blow at him, on the condition that the Green Knight will return the blow one year and one day later. Sir Gawain, the youngest of Arthur's knights as well as Arthur's nephew, accepts the challenge and chops off the giant's head in one smashing blow, fully expecting him to die. But the Green Knight picks up his own head, reminds Gawain to meet him at the Green Chapel in a year and a day, and rides off.

Almost a year later, Sir Gawain sets off to find the Green Chapel and complete his bargain with the Green Knight. His journey takes him to a beautiful castle, where Gawain meets Bercilak, the lord of the castle, and his beautiful wife, who are both pleased to have such a renowned guest. Gawain tells them of his New Year's Day appointment at the Green Chapel and says that he must continue his search the next day. The lord laughs and tells him his search has ended: the Green Chapel is not two miles away.

The lord of the castle goes hunting the next day, and proposes a bargain to Gawain before he leaves: he will give Gawain whatever he catches, on condition that Gawain will give to the lord whatever he might gain during the day. Gawain accepts. After the lord has gone, the lady of the castle visits Gawain's bedroom to seduce him. Gawain, however, yields in nothing but a single kiss. When the lord returns with the deer he has killed, as agreed, Gawain responds by returning the lady's kiss to the lord, but avoids explaining its source. The next day, the lady comes again, Gawain dodges her advances, and there is a similar exchange of a hunted boar for two kisses. She comes again on the third morning, and Gawain accepts from her a green silk girdle, which the lady promises will keep him from all physical harm. They exchange three kisses. That evening, the lord returns with a fox, which he exchanges with Gawain for the three kisses. However, Gawain keeps the girdle from the lord.

The next day, Gawain leaves for the Green Chapel with the lady's silk girdle. He finds the Green Knight there sharpening an axe, and, as arranged, bends over to receive his blow. The Green Knight swings to behead Gawain, but holds back twice, only striking softly on the third swing, causing a permanent scar on his neck. The Green Knight then reveals himself to be the lord of the castle, Bercilak de Hautdesert and explains that the whole game was arranged by Morgan le Fay. Gawain is at first upset, but the two men part on cordial terms and Gawain returns to Camelot, wearing the girdle as a badge of shame. Arthur, however, decrees that all his knights should henceforth wear a green sash in recognition of Gawain's adventure.

The poet

Though the name of "The Gawain Poet" (or poets) is unknown, some inferences about him can be drawn from an informed reading of his works. The manuscript of Gawain is known in academic circles as Cotton Nero A.x, following a naming system used by one of its owners, Robert Cotton, a collector of English manuscripts.[2] Before the Gawain manuscript came into the possession of Robert Cotton, it was in the library of Henry Savile of Bank in Yorkshire.[3][4] Little is known of it, or its author, before that. It has been dated to the late 14th century, so the poet was a contemporary of Geoffrey Chaucer, though remote from him in almost every other way.[5] Also, the three other works found with the Gawain manuscript, (commonly known as Pearl, Patience, and Cleanness (alternatively Purity)) are often considered to be written by the same author. However, the manuscript containing these poems was written by a copyist and not by the original poet.[6] There is thus nothing explicit suggesting all four poems in the manuscript are by the same poet. However, comparative analysis of dialect, verse form, and diction has caused scholars to generally accept single-authorship.[6] Consensus on the issue, however, remains elusive.

What is known today about the poet himself is largely general knowledge, as J. R. R. Tolkien, in the introduction to his translation, writes:

He was a man of serious and devout mind, though not without humour; he had an interest in theology, and some knowledge of it, though an amateur knowledge perhaps, rather than a professional; he had Latin and French and was well enough read in French books, both romantic and instructive; but his home was in the West Midlands of England; so much his language shows, and his metre, and his scenery.[7]

The most commonly suggested candidate for authorship is John Massey of Cotton, Cheshire.[8] One additional poem, St. Erkenwald, has sometimes been attributed to the same poet. St. Erkenwald is found in a manuscript separate from the Gawain manuscript, which has been dated by some scholars to a time outside the poet's era. Ascribing authorship of St. Erkenwald to the Pearl Poet is still controversial and generally rejected.[6]

Verse form

| Translation:

(bob) |

| — SGGK lines 146-150[9] |

| An example of bob and wheel in Gawain

(bob) |

| — SGGK lines 146-150[9] |

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is written in a style typical of the what is called by linguists the "Alliterative Revival" of the 14th century. Instead of focusing on a metrical syllabic count and rhyme, the alliterative form of this period usually relied on the agreement of a pair of stressed syllables at the beginning of the line and another pair at the end of the line. The line always finds a "breath-point", or pause, called a caesura, at some point after the first two stresses, dividing the line into two half-lines.[1]

Although he largely follows the form of his day, the Gawain poet was somewhat more free with convention than his predecessors. The poet broke his alliterative lines into variable-length groups and ended these nominal stanzas with a rhyming section of five lines known as the bob and wheel: one one-stress line rhyming a (the bob) and four three-stress lines rhyming baba (the wheel). These lines also alliterated.[1] On the whole, the poem takes up 2530 lines, divided into four parts and 101 stanzas.[9]

Similar stories

The earliest known story with a beheading game element is the Middle Irish tale Bricriu's Feast. This story parallels Gawain in several ways. For example, like the Green Knight, Cúchulainn's antagonist feints three blows with the axe before letting him without injury. A beheading exchange also appears in the Life of Caradoc, a Middle French narrative embedded in the anonymous First Continuation of Chrétien de Troyes' Perceval, the Story of the Grail. In this story, a notable difference is that Caradoc's challenger is his father in disguise, come to test his honor. Lancelot is given a beheading challenge in Perlesvaus, where a knight comes and begs him to chop off his head, or else put his own in jeopardy. Lancelot reluctantly cuts it off, under the agreement that he will come to the same place in a year to put his head in the same danger. When Lancelot arrives, the people of the town celebrate and announce that they have finally found a true knight (apparently many knights had been tested, and failed). The Girl with the Mule (alternately titled The Mule Without a Bridle) and Hunbaut feature Gawain in beheading game situations. Hunbaut has an interesting twist: Gawain cuts off the man's head, then pulls off the magic cloak keeping the man alive before he can replace his head, causing his death.[10] There are also several stories in which knights struggle to stave off the advances of voluptuous women, including Yder, the Lancelot-Grail, Hunbaut, and The Knight of the Sword. The last two involve Gawain specifically. Usually the temptress is the daughter or wife of a lord to whom the knight owes some respect, and the knight is tested in whether or not he will remain chaste in extreme circumstances.[10]

The Greene Knight is a rhyming retelling of what is almost the same story as Gawain.[11] The plot is simplified, there is more extensive explanation of motive, and some of the names are changed. Another retelling, The Turke and Gowin begins with a Turk entering Arthur's court and asking, "Is there any will, as a brother, To give a buffett and take another?"[12] In the end of this poem, the Turk, rather than buffeting Gawain back, asks the knight to cut off his head, which Gawain does. The Turk then praises Gawain and showers him with gifts. The Carle off Carlile also compares to Gawain in a scene in which the Carl, a lord, orders Gawain to strike him with his spear, and bends over to receive the blow.[13] Gawain obliges and attacks, but the Carl rises, laughing and unharmed. Unlike the Gawain poem, no return blow is demanded or given.[10] Among all these stories, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is the only one with a completely green character, and the only one tying Morgan le Fay to the game involved.[10][12]

Themes

Hunting and seduction

Scholars have frequently noted the parallels between the three hunting scenes and the three seduction scenes in Gawain. They are generally agreed that the fox chase scene has significant parallels to the third seduction scene, in which Gawain accepts the girdle from Bercilak's wife. Gawain, like the fox, fears for his life and is looking for a way to avoid death under Bercilak's axe. He also, like his counterpart, resorts to trickery in order to save his skin. The fox uses tactics so unlike the first two animals, and so unexpected, that Bercilak has a harder time hunting it than the other two animals. Similarly, Gawain finds the woman's advances in the third seduction scene more unpredictable and challenging to resist than her previous attempts. She changes her language from the more evasive style typical of courtly love relationships to a more assertive style. Her dress, relatively modest before, is suddenly voluptuous and revealing in nature. All of these things are considered easily connected by scholars.[14]

The deer and boar scenes are a bit harder to connect. Scholars have attempted to connect each animal to Gawain's reactions in the parallel seduction scene. Attempts to connect the deer hunt with the first seduction scene have unearthed a few parallels. Deer hunts of the time, like courtship, had to be done by the book. Women often favored suitors by how well they hunted and skinned their animal, sometimes even looking on while the deer was cleaned.[14] The "hyndez" (hinds) first described are probably red deer, a species with large antlers like the American elk, while the subsequent "dos and of oþer dere" (does and other deer) likely refer to the smaller fallow deer.[15] The sequence describing the deer hunt is relatively unspecific and nonviolent, with an air of relaxation and exhilaration. The first seduction scene follows a similar vein, with no overt physical advances; the whole exchange of seduction being portrayed in a humorous way. There is no apparent danger.[14]

The boar scene has a lot more detail. Boars at the time were much more difficult to hunt than deer. To take one on with nothing but a sword was akin to challenging a knight to single combat. In the hunting sequence, the boar at first flees, but is eventually cornered in a ravine. He turns to face Bercilak with his back to the ravine, prepared to fight. Bercilak dismounts, and in the ensuing fight, manages to kill the boar. He removes its head is and sets it on high. In the seduction scene, Bercilak's wife, like the boar, is a bit more forward, insisting that she knows that Gawain has quite a romantic reputation, and that she deserves a taste of it. Gawain, however, is successful in parrying her attacks, saying that surely she knows more than he about love already. Both the boar and the seduction scene can be seen as depictions of a moral victory.[14]

Nature vs. chivalry

William F. Woods argues for nature’s influence on the story and characters of the poem. Woods presents nature as a major theme in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight—representing a form of chaotic order inherent through out the poem. The green horse and rider that first invade the Arthur’s peaceful halls can be seen as icons representing the disturbance of nature and such chaos (213). Nature itself is presented in the poem as rough and indifferent, ever threatening the order of men and courtly life (215). As the poem progresses, one can see nature come to invade and disrupt such order in the major events (symbolically or through the elemental inner nature of man)—first with the disruption of the Green Knight (213), then later when Gawain must fight off the temptations of Bertilak’s wife (220), and finally when Gawain breaks his vow to Bertilak and the Green Knight by choosing to keep the green girdle and choosing his personal survival rather than virtue (222). Nature is an underlying force that seems to be a part of man that keeps him forever imperfect (in a chivalric sense), as represented by the sin stained girdle (222).

While Woods claims that nature provides a stronger order in the poem (a different kind of perfection), Richard Hamilton Green believes that the poet aims at the quest for chivalric perfection over nature. According to Green, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight “embodies the chivalric ideals of the English ruling class (121).” Green too recognizes nature as another force in the poem (with the Green Knight representing this “world of mystery (125)”), but rather than present it as an inevitable ruler over man he asserts that the author creates a “dark world of potential failure” and warns “of powers of evil which may corrupt even the most virtuous men and institutions (123).” There is a subtle difference between authors—while Woods claims that the Pearl Poet removes responsibility from Gawain’s actions through nature, Green argues that chivalry is the greater and more virtuous order presented by the poet. Gawain, himself, is to represent the heroic ideal in the poem yet still has his shortcomings—the poet does not “transform vice into virtue for the sake of the general comfort (129).” Gawain truly is imperfect, and it is through his lesson of humility that he finds redemption (129).

Games

The word 'gomen' (game) is found eighteen times in Gawain. Its relation to the word 'gome' ('man') which is in the poem 21 times has led some scholars to draw a connection in meaning, possibly as a representation of man's fallen nature in the Christian sense.[16] Games at this time may also be seen as a test of worthiness, as, for example, the Green Knight challenges the court's worthiness of its good name in a "Christmas game."[16] The "game" of exchanging gifts was actually very common in Germanic cultures. If a man was given a gift, he had to give the giver a better gift, or risk losing his honor, almost like an exchange of blows in a fight (or in a "beheading game").[17] The poem revolves around two games – first an exchange of beheading, and secondly an exchange of winnings. The two appear at first to be unconnected. However, it is later revealed that the hero's survival of the first game at the conclusion of the story depends on his honesty, while his second victory depends on his purity. Again, both elements appear in other stories, the beheading game appearing first in the Middle Irish narrative Bricriu's Feast. However, the linkage of outcomes is unique to this story.[1][7]

Times and seasons

Times, dates, seasons, and cycles within Gawain are often noted by scholars. The story starts on New Year's Day with a beheading, and culminates on the next New Year's Day. Gawain leaves Camelot on All Hallows Day (or All Saints Day), and arrives at Bercilak's castle on Christmas Eve. Further, the Green Knight tells Gawain to meet him at the Green chapel in "a year and a day"—a period of time seen often in medieval literature. Some scholars interpret these cycles of time, each beginning and ending in winter, as the poet's attempt to convey the inevitable fall of all things good and noble in the world. Imagery of inevitable fall is strengthened by the image of the fall of Troy. The entire poem is set between two virtually identical descriptions of its destruction, the first line being: "SIÞEN þe sege and þe assaut watz sesed at Troye", and the final stanzaic line (before the bob and wheel) being "After þe segge and þe asaute watz sesed at Troye."[18]

Symbolism

Significance of the colour green

Given the varied and even contradictory interpretations of the colour green, its precise meaning in the poem remains ambiguous. In English folklore and literature, Green has traditionally been used to symbolize nature and its embodied attributes, namely those of fertility and rebirth. Stories of the medieval period further portray it as representing love[20] and the base, natural desires of man.[21] Green is also known to have signified witchcraft, devilry and evil for its association with faeries and spirits of early English folklore. It also had an association with decay and toxicity.[22] The color, when combined with gold, as is the case with both the Green Knight and the girdle, is seen as representing the fading away of youth.[23] In the Celtic tradition, green was avoided in clothing for its superstitious association with misfortune and death. The green girdle, originally worn for protection, transforms into a symbol of shame and cowardice. Then it is finally adopted as a symbol of honour by the knights of Camelot, signifying a transformation from good to evil and back again displaying both the spoiling and regenerative connotations of the colour green.[24][25]

The Green Knight

The Green Knight appears in two other works already mentioned, The Greene Knight and the fragmentary ballad "King Arthur and King Cornwall",[26] both of which give his name as "Bredbeddle". The Greene Knight tells essentially the same story as Sir Gawain, whereas "King Arthur and King Cornwall" is a unique narrative in which the Green Knight is one of Arthur's champions.

Characters similar to the Green Knight appear in several other works. In Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, for example, Gawain's brother Gareth fights "two brethren whych were called the Grene Knyght and the Rede Knyght". The stories of Saladin also feature a certain "Green Knight"; he is a Sicilian warrior in a shield vert and a helmet brandished with a stag's horns. Saladin had respect for this honourable fighter and tried to make him part of his personal guard.[27] The figure of Al-Khidr in the Qur'an is called the "Green Man" (Arabic: الخضر). He tests Moses three times by doing seemingly evil acts, which are eventually revealed to be noble deeds to prevent greater evils or reveal great goods. Both the Green Knight and Al-Khidr serve as teachers to holy and upright men (Gawain, Moses), who thrice put their faith and obedience to the test. It has been suggested that the character of the Green Knight may be a literary descendant of Al-Khidr, brought to Europe with the Crusaders and blended with Celtic and Arthurian imagery.[28]

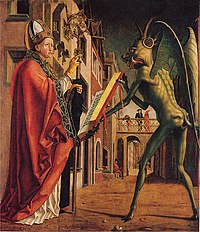

Despite these similarities, the Green Knight is the first of his character parallels to be green.[29] Because of his strange color, many scholars believe him to be a manifestation of the Green Man figure common in medieval art.[24] Others see him as being an incarnation of the Devil himself.[24] In one interpretation, it is thought that the Green Knight, as the "Lord of Hades," has come to challenge the noble knights of King Arthur's court. Sir Gawain, the bravest of the knights, therefore proves himself the equal to Hercules in challenging the Knight, tying the story to ancient Greek mythology.[22] Another possible interpretation of the Green Knight is to view him as a fusion of these two deities, at once representing both good and evil and life and death as self-proliferating cycles. This interpretation embraces the positive and negative attributes of the colour green and ties in with the enigmatic motif of the poem.[24]

The pentangle

The pentangle on Gawain's shield is seen by many critics as having special significance in the poem. It is the first time the word 'pentangle' is known to have been used in English, and is the only time it is associated with Gawain's shield. Usually, Gawain is said to have an eagle symbol on his shield.[30] The poem describes the pentangle as a sign descended from Solomon's time, a symbol of faithfulness, and an "endless knot." It spends several stanzas carefully outlining the virtues of Gawain, represented by the five points of the pentangle.[30] The emphasis the poet places on the pentangle has even caused some scholars to believe it to be an allegory or representation for the entire poem.[30]

Academics compare the pentangle to the traditional pentagram, which was said to have magical properties. In Germany, it was called a Drudenfuss and was placed on household objects to keep evil out of the house.[31] The symbol was also associated with magical charms which, if recited or written on a weapon, would call forth magical forces. However, the concrete evidence tying the magical pentagram to Gawain's pentangle is scarce.[32][31]

Others point out the description of the pentangle in line 625 as "a sign by Solomon”. Solomon, the third king of Israel in 10th century B.C., is usually referred to as having great wisdom. In Gawain, however, the poet refers to the magic seal on his ring, the mark of the pentagram, which he received from the archangel Michael. The seal gave Solomon power over demons.[33]

The girdle

- See also: The girdle in literature

Critics often debate whether the girdle which Gawain receives from Bercilak's wife has sexual meaning. Proponents compare the girdle to other stories of the culture, such as Nibelungenlied. In this story Brunhilde is convinced that she has had intercourse with the wrong man on seeing her stolen girdle produced as evidence.[34] Feminist interpretations see the girdle (called a "love lace" at one point in the text) as a symbol of feminine power. They point out the definition of "lace" at the time, which along with the "article of clothing," also meant "net," "noose," or "snare."[35] Critics who see the poem through a Christian lens see Gawain's trust in the girdle as a replacement for his trust in God to save him from the axe-wound.[36] Notions of the image of the girdle as a "sexual symbol," however, should not be confused with modern notions of a girdle as "underwear".[37][34] A girdle in the days of the Pearl-Poet was, “a belt worn around the waist, used for fastening clothes or for carrying a sword, purse, etc.” This is similar to the definition of girdle at the time of Nibelungenlied's writing.[38]

The specific girdle given to Gawain is “Of a gay green silk, with gold overwrought,”[39] which likely was intended to hearken to the Green Knight’s colour of choice. The correlating fox that is caught at the time as Gawain gains the girdle, is given the name “Sir Reynard the Red”,[40] whose hide is stripped away. Two more important images are here visible in regards to the tempted Arthurian knight. Firstly, the colour imagery, and secondly the hide, or fur, of the fox can also be seen as symbolically stripped. Red is found at least upon Sir Gawain’s shield,[41] if not in more places, and the image of the fur is early established as representing a certain humble-nature belonging to Sir Gawain.[42]

Interpretations

Christian interpretations

Christian interpretations of the poem take many forms. The shield on which the pentangle is emblazoned can be seen as symbolizing Gawain's faith in the protection of God and Christ.[16] Some critics compare Sir Gawain to the other three poems of the Gawain manuscript. Each has a heavily Christian theme, causing scholars to see Gawain through a similar lens. Comparing it to the poem Cleanliness (also known as Purity), for example, they see it as a story of the apocalyptic fall of a civilization, in Gawain's case, Camelot. In this interpretation, Sir Gawain is like Noah, separated from his society and warned by the Green Knight (who is seen as God's representative) of the coming doom of Camelot.[18] Gawain, judged worthy through his test, is spared the doom of the rest of Camelot. King Arthur and his knights, however, misunderstand Gawain's experience and wear garters themselves. In Cleanliness the men who are saved “cannot spare their respective societies from divine justice, and in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Gawain alone cannot stave off the fall of Camelot, although his adventure can serve to underscore the inevitability of that society’s demise to those who can read it correctly."[18] One of the key points stressed by this similarity indicates “. . . that divinely accorded revelation and salvation can only be experienced directly and individually and are therefore incapable of being translated back into the world of the unredeemed."[18] Through this depiction of Camelot, the Gawain poet reveals a concern for his society, whose fall he feels is unavoidable and will bring about ultimate destruction as intended by God.[18]

The poem was written around the time of the Black Death and Peasant's Revolt, events which gave people the idea that their world truly was going to meet an apocalyptic end, influencing literature and culture.[18] Other critics see faults in this view because ultimately the Green Knight is under the control of Morgan le Fay, who is usually a strong figure of evil in Camelot tales. This makes it difficult to see him as a representative of God in any way.[16]

While the character of the Green Knight is usually not regarded as an actual representation of Christ in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, critics do acknowledge a parallel. Lawrence Besserman explains that "[t] he Green Knight is not a figurative representative of Christ. But the idea of Christ's divine/human nature provides a medieval conceptual framework that supports the poet's serious/comic account of the Green Knight's supernatural/human qualities and actions.[24] This parallel in duality exemplifies the influence and importance of Christian teachings and views of Christ in the era of the Gawain Poet.

Furthermore, critics note the Christian influence paralleled at the conclusion of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. After Gawain returns to Camelot and tells his story regarding the newly aquired green sash, the poem is concluded with a brief prayer and a reference to "the thorn-crowned God."[43] Besserman theorizes that "with these final words the poet redirects our attention from the circular girdle-turned-sash (a double image of Gawain's "yntrawpe/renoun") to the circular Crown of Thorns (a double image of Christ's humiliation/triumph)."[24]

Throughout the poem, Gawain encounters numerous trials testing his devotion and faith in Christianity. When Gawain sets out on his journey to find the Green Chapel, he finds himself in distress, and only after praying to the Virgin Mary does he escape trouble. As he continues further in his journey, Gawain once again faces anguish regarding his inevitable encounter with the Green Knight. Instead of praying to Mary, as before, Gawain places his faith into the girdle given to him by Bertilak’s wife.[44] From the Christian perspective, this leads to disastrous and embarrassing consequences for Gawain as he is forced to reexamine and reevaluate his faith and Christian principles after the girdle turns out to be nothing more than a hoax.[44]

In addition, an analogy is made between Gawain’s trial and the test that Adam encounters in Eden, as described in the Bible. Adam succumbed to Eve, just as Gawain surrendered to Bertilak’s wife by accepting the false idea of the girdle.[44] While Gawain does sin, both by putting his faith in the girdle and by not confessing once he is caught, the Green Knight pardons him and “. . . allows Gawain to metamorphose into a better Christian through his very failures."[45] Through the various games played and hardships endured Gawain understands and finds his place within the Christian world.

Feminist interpretations

Feminist literary critics see the poem as portraying womens' ultimate power over men. Morgan le Fay and Bertilak's wife, for example, are the most powerful characters in the poem—Morgan especially, as she enchanted the Green Knight and started the entire game. The girdle and Gawain's neck-scar can be seen symbols of feminine power, each of them bringing the praised manhood of Gawain down. Gawain's passage of rhetorical anti-feminism,[46] in which he blames all of his troubles on women and outlines the many men who have fallen to women's wiles, further supports the feminist view of ultimate female power in the poem by Gawain's own admission.[35]

Romantic Interpretation

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight should be viewed, above all, as a romance. Sir Gawain embodies all of the characteristics of an ideal Arthurian knight. “He is not, to be sure, an average man, nor is he the counterpart of any single knight who ever lived; on the contrary, he is the very best knight who sums up in his character the very best traits of all knights who ever lived.”[47] He is an instrument of “courage, humility, courtesy, and loyalty."[47] Sir Gawain’s character is one of remarkable morals and infallible manners. His position as Arthur’s nephew mirrors his ideal personal characteristics.[47] “He is the ideal feudal Christian knight who not only represents the very highest reaches of human behavior but who also holds out for our evaluation those qualities in a man which his age, and the feudal age at large, admired most.”[47]

Sir Gawain’s only slip is the acceptance of the lady’s girdle. “Though the greatest knight, he remains only human.”[48] This acceptance may be seen as an act of pride, and Gawain’s wound as a punishment for that pride. And “…when Gawain is nicked in the neck, the court‘s neck is also nicked. Each receives the blade in order to be relived of stiff-necked pride. Gawain is the neck of the court and, with Arthur, it’s head: he is Arthur’s most steadfast supporter, he is the court’s greatest source of chivalric pride, and he is the finest knight of the courtly body in prowess and courtesy.”[48] Nevertheless, this fault underlines Gawain’s humanity. At the end of the poem, Sir Gawain’s reaction to the Green Knight’s knowledge of the girdle is emotional. He is embarrassed by his failure.[48] Sir Gawain underlines the fact that many great men have been tempted by women. But he is “All the more human for this slight fault.”[47] This failure makes Sir Gawain more real and it evokes sympathy from the reader. In The Meaning of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight , Alan Markman says, “It is the function of the romance hero, I think to stand as the champion of the human race, and by submitting to strange and severe tests, to demonstrate human capabilities for good or bad action.”[47]

The reader becomes attached to this human view of Gawain in the midst of the poem’s romanticism. This single flaw shows Gawain’s humanity, but it does not undermine all of his knightly qualities. Gawain “shows us what moral conduct is. We shall probably not equal his behavior, but we admire him for pointing out the way.”[47]

Sir Gawain and Colonialism

Historically, England was at war with Wales in an attempt to gain more territory throughout 1350-1400, the period the poem is purported to have been written in,[49], and the Gawain poet is believed to have used a North-Western midlands dialect common on the Welsh English border.[49]

Though the initial idea of viewing the poem within the context of a colonial struggle is credited to Patricia Clare Ingham,[49] there is a great deal of dispute over the extent to which colonial differences actually play a role in the poem.[49] Most critics agree that gender plays a role in the poem but differ about whether gender supports the colonial ideals or replaces them as the two cultures interact in the poem.[49]

There is also a large amount of critical debate surrounding the political landscape at the time. Rhonda Knight argues that Bertilak is an example of hybrid Anglo-Welsh culture found on the English/Welsh border;[49] similarly, Ingham sees the poem as a reflection of a hybrid culture that plays the existing cultures strong cultures off of each other to create something new.[49] In contrast to these opinions, Arner argues that historically a lot of Welsh blood was shed well into the 14th Century, creating a situation far removed from the more friendly hybridization suggested by Knight and Ingham.[49] To further support her argument, Arner posits that the poem creates an “us versus them” scenario which contrasts the knowledgeable, civilized English with the uncivilized borderlands that are home to Bertilak and all of the other monsters Gawain encounters on his quest.[49]

In contrast to this perception of the colonial lands, Bonnie Lander argues that the land of Hautdesert (Bertilak’s territory) has been misrepresented or ignored in modern criticism and posits that it is a land with it’s own moral agency that plays a central role in the story (Lander 43-4). Lander argues that the denizens of Hautdesert are “intelligently immoral” (Lander 44), choosing to follow certain codes and reject others, a position which creates a “distinction…of moral insight versus moral faith.” (Lander 44) Lander thinks that the border dwellers are more sophisticated because they don’t unthinkingly embrace the chivalric codes, but challenge them in a philosophical, and in the case of the appearance of Bertilak at Arthur’s court, very literal sense (Lander 44). Lander’s argument about the superiority of the denizens of Hautdesert hinges on the lack of self-awareness present in Camelot (Lander 45), which leads to an unthinking populous that frowns on individualism (Lander 46). Lander presents an interesting counter-point to the praise of Arthur and demonizing of Bertilak and the colonial border lands present throughout Arner’s article.

The Order of the Garter

Gawain, along with following the rules of knighthood (chivalry), is confronted with a situation in the seduction scenes which challenges his knowledge of the intricacies of courtly love laws. (Courtly love was a medieval phenomenon outlining the rules of romantic pursuit.) Thus, many scholars see this poem as the story of the intertwining of chivalric and courtly love laws under the guise of the English Order of the Garter. The motto at the end of the poem is a form of 'honi soit qui mal y pense', meaning "Shame be to the man who has evil in his mind." This is the motto of the Order of the Garter. It has been theorised that Gawain's peers wearing girdles of their own is meant to represent the origin of the Order of the Garter. However, in the parallel poem, The Greene Knight, the lace is white, not green, and is said to be the origin of the collar worn by the knights of the Bath, not the Order of the Garter.[50] The motto on the poem was probably written by a copyist and not by the author of the poem. Still, the connection this copyist made to the Order is not a difficult one to make.[51]

Gawain's journey

Several scholars have attempted to piece together the facts in the poem about Gawain's journey to the Green Chapel to see their correspondence to a real-world map. The Anglesey islands, for example, are mentioned in the journey. They exist today as a single island off the coast of Wales.[52] In line 700, Gawain is said to pass the "Holy Head", believed by many scholars to be either Holywell or the Cistercian abbey of Poulton in Pulford. Holywell is associated with the beheading of St. Winifred. As the story goes, Winifred was a virgin in the area who was beheaded by a local leader after she refused his sexual advances. Her uncle, another saint, placed her head back in its place and healed the wound, leaving only a white scar. The parallels between this story and Gawain's make this area a likely candidate for the journey.[53] Strangely, Gawain's journey leads him directly into the centre of the Pearl Poet's dialect region, where the candidates for the locations of the Castle at Hautdesert and the Green Chapel stand. Hautdesert is thought to be in the area of Swythamley in northwest Midland, as it is in the writer's dialect area, and matches the land features described in the poem. The area is also known to have housed all of the animals hunted by Bertilak (deer, boar, fox) in the 14th century.[54] The Green Chapel is thought to be in either Ludchurch or Wetton Mill, as these areas closely match the descriptions given by the author.[55]

Modern adaptations

- Gawain (first performed 1991), an opera based on the poem[56]

- Gwyneth and the Green Knight, another opera in which the original story is a backdrop for the story of Gwyneth, a woman who wants to be a knight.[57]

- Sword of the Valiant: The Legend of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1984), a film featuring Miles O'Keefe as Gawain and Sean Connery as The Green Knight[58]

- Gawain and the Green Knight (1973), a film[59]

- Sword of the Valiant: The Legend of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1984), a film featuring Miles O'Keefe as Gawain and Sean Connery as The Green Knight[60]

- Gawain and the Green Knight (1991), a television adaptation[61]

- Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (2002), an animated television adaptation[62]

In 1925, J. R. R. Tolkien published a translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.[63] Many editions of the work list Tolkien on the cover as the author, rather than editor/translator.[64] It is therefore common to see this work erroneously referenced as a Tolkien original.[65]

References

- ^ a b c d The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt. 8th ed. Vol. B. New York, London: W. W. Norton and Co., 2006. pgs. 19-21 & 160-161.

- ^ a b "Web Resources for Pearl-poet Study: A Vetted Selection". Univ. of Calgary. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- ^ "Pearl: Introduction". Medieval Institute Publications, Inc. 2001. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- ^ "SIR HENRY SAVILE (1549–1622)". Encyclopedia Britannica. 1911. Retrieved April 3, 2007.

- ^ "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight." The Broadview Anthology of British Literature: The Medieval Period. Vol. 1. ed. Joseph Black, et al. Toronto: Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55111-609-X Intro pg. 235

- ^ a b c The Pearl-Poet", William Nelles, Cyclopedia of World Authors, Fourth Revised Edition Database: MagillOnLiterature Plus

- ^ a b Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Edited JRR Tolkien/EV Gordon, revised Norman Davis, introduction, xv

- ^ Peterson, Clifford J. "The Pearl-Poet and John Massey of Cotton, Cheshire." The Review of English Studies, New Series 25.99 (1974) pp. 257-266

- ^ a b c http://rpo.library.utoronto.ca/poem/62.html

- ^ a b c d Brewer, Elisabeth. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight : sources and analogues. 1992

- ^ Hahn, Thomas (2000). "The Greene Knight". In Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications. ISBN 1-879288-59-1. Full text: The Greene Knight

- ^ a b Hahn, Thomas (2000). "The Turke and Sir Gawain". In Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications. ISBN 1-879288-59-1. Online: The Turke and Sir Gawain.

- ^ Hahn, Thomas (2000). "The Carle of Carlisle". In Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications. ISBN 1-879288-59-1. Online: The Carle of Carlisle.

- ^ a b c d Burnley, J. D. "The Hunting Scenes in 'Sir Gawain and the Green Knight'." The Yearbook of English Studies. (1973) 3 pgs. 1-9

- ^ Ong, Walter J. "The Green Knight's Harts and Bucks." Modern Language Notes. (Dec 1950) 65.8 pgs. 536-539

- ^ a b c d Lauren M. Goodlad (1987) "The Gamnes of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight", Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies: Vol. 18, Article 4.

- ^ Harwood, Britton J. "Gawain and the Gift." PMLA 106.3 (1991): 483-99.

- ^ a b c d e f Clark, S. L., and Julian N. Wasserman. "The Passing of the Seasons and the Apocalyptic in "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight"." South Central Review 3.1 (1986): 5-22.

- ^ Robertson, D. W. Jr. "Why the Devil Wears Green." Modern Language Notes. (Nov 1954) 69.7 pgs. 470-472

- ^ Chamberlin, Vernon A. "Symbolic Green: A Time-Honored Characterizing Device in Spanish Literature." Hispania. 51.1 (Mar 1968) pp. 29-37

- ^ Goldhurst, William. "The Green and the Gold: The Major Theme of Gawain and the Green Knight." College English. 20.2 (Nov 1958) pp. 61-65 doi:10.2307/372161

- ^ a b Williams, Margaret. The Pearl Poet, His Complete Works. Random House, 1967.

- ^ Lewis, John S. "Gawain and the Green Knight." College English. 21.1 (Oct 1959) pp. 50-51

- ^ a b c d e f The Idea of the Green Knight, Lawrence Besserman, ELH, Vol. 53, No. 2. (Summer, 1986), pp. 219-239. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Why The Devil Wears Green, D. W. Robertson Jr., Modern Language Notes, Vol. 69, No. 7. (Nov., 1954), pp. 470-472. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Hahn, Thomas (2000). "King Arthur and King Cornwall". In Sir Gawain: Eleven Romances and Tales. Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications. ISBN 1-879288-59-1.

- ^ Richard, Jean. An Account of the Battle of Hattin Referring to the Frankish Mercenaries in Oriental Moslem States Speculum 27.2 (1952) pp. 168-177.

- ^ Lasater, Alice E. (1974). Spain to England: A Comparative Study of Arabic, European, and English Literature of the Middle Ages. University Press of Mississippi.

- ^ Krappe, A. H. "Who Was the Green Knight?" Speculum. (Apr 1938) 13.2 pgs. 206-215

- ^ a b c Ann Derrickson (1980) "The Pentangle: Guiding Star for the Gawain-Poet". Comitatus: A Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Vol. 11, Article 2.

- ^ a b Hulbert, J. R. "Syr Gawayn and the Grene Knyzt-(Concluded)." Modern Philology. (Apr 1916) 13.12 pgs. 689-730.

- ^ Jackson, I. "Sir Gawain's Coat of Arms." The Modern Language Review. (Jan 1920) 15.1 pgs. 77-79.

- ^ LaBossière, Camille R., & Gladson, Jerry A. (1992). Solomon. In A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature (Page 722). William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company: Grand Rapids, Michigan.

- ^ a b Friedman, Albert B., and Richard H. Osberg. "Gawain's Girdle as Traditional Symbol." The Journal of American Folklore 90.357 (1977): 301-15.

- ^ a b Heng, Geraldine. "Feminine Knots and the Other Sir Gawain and the Green Knight." PMLA 106.3 (1991): 500-14.

- ^ Berger, Sidney E. (1985). "Gawain's Departure from the Peregrinatio". West Virginia University Press. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- ^ Bloomfield, Morton W. (1961). Sir Gawain and the Green Knight: An Appraisal. PMLA, 76, 16.

- ^ Middle English Dictionary (as cited in Friedman, Albert B., & Osberg, Richard H. (1977). Gawain's Girdle as Traditional Symbol. The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 90, No. 357, pp. 301-315.)

- ^ ll. 1832

- ^ ll. 1920

- ^ ll. 619

- ^ Woods, William F. (2002). Nature and the inner man in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The Chaucer Review, 36.3, 209-227, pg. 217

- ^ Sir Gawain and the Green Knight ln. 2529

- ^ a b c Cox, Catherine. "Genesis and Gender in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight." The Chaucer Review 35. 4(2001) 379-390. 22 September 2007 <http://muse.jhu.edu/content/z3950/journals/chaucer_review/v035/35.4cox.html>

- ^ Pugh, Tison. "Gawain and the Godgames." Christianity and Literature 51. 4(2002) 526-551. 30 September 2007 <http://vnweb.hwwilsonweb.com.ezp.slu.edu/hww/results/external_link_maincontentframe.jhtml?_DARGS=/hww/results/results_common.jhtml.9>

- ^ David Mills, 'The Rhetorical Function of Gawain's Antifeminism?', Neuphilologische Mitteilungen, 71 (1970), 635-4

- ^ a b c d e f g Markman, Alan M. "The Meaning of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight." PMLA. (Sep 1957) 72.4 pgs. 574-586

- ^ a b c Farrell, J. Thomas, Patrick D. Murphy, Richard H. Osberg, Paul F. Reichardt. Gawain’s Wound. PMLA, Vol. 100, No.1. (Jan,1985), pp.97-99. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0030-8129%28198501%29100%3A1%3C97%3AGW%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Z

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Arner, Lynn. "The Ends of Enchantment: Colonialism and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight." Texas Studies in Literature and Language. (Summer 2006) 48.2 pgs. 79-101.

- ^ Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, edited by JRR Tolkien and EV Gordon second edition, note to lines 2514ff

- ^ The Norton Anthology of English Literature. Ed. Stephen Greenblatt. 8th ed. Vol. B. New York, London: W. W. Norton and Co., 2006. pg. 213 (footnote).

- ^ Twomey, Michael. "Anglesey and North Wales". Travels With Sir Gawain. Ithaca Univ. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Twomey, Michael. "The Holy Head and the Wirral". Travels With Sir Gawain. Ithaca Univ. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Twomey, Michael. "Hautdesert". Travels With Sir Gawain. Ithaca Univ. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Twomey, Michael. "The Green Chapel". Travels With Sir Gawain. Ithaca Univ. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Who is Gawain?". Retrieved April 13, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Gawain and the Green Knight (1973)". Retrieved April 13, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Opera: Gwyneth and the Green Knight". Retrieved April 13, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Gawain and the Green Knight (1973)". Retrieved April 13, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Sword of the Valiant: The Legend of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (1984)". Retrieved April 13, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Gawain and the Green Knight (1991) (TV)". Retrieved April 13, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (2002) (TV)". Retrieved April 13, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Scholar, J.R.R. Tolkien Fanlisting)". Retrieved May 7, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Tolkien Bibliography". Retrieved May 7, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Old Poetry: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight by J.R.R. Tolkien". Retrieved May 7, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Farrell, J. Thomas, Patrick D. Murphy, Richard H. Osberg, Paul F. Reichardt. Gawain’s Wound. PMLA, Vol. 100, No.1. (Jan,1985), pp.97-99. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0030-8129%28198501%29100%3A1%3C97%3AGW%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Z

Markman, M. Alan. The Meaning of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. PMLA, Vol. 72, No.4. (Sept.,1957) pp.574-586. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0030-8129%28195709%2972%3A4%3C574%3ATMOSGA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-6