Fraktur

| Latin script (Fraktur hand) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | 16th – mid-20th centuries |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | German¹ and some other European languages |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Blackletter

|

Child systems | Kurrentschrift, including Sütterlin |

Sister systems | See Blackletter |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Latf (217), Latin (Fraktur variant) |

| Unicode | |

0020–00FF² | |

Fraktur [fʁakˈtuːɐ] is a calligraphic hand and any of several blackletter typefaces derived from this hand. The word derives from the past participle fractus ("broken") of Latin frangere ("to break"); the same root as the English word 'fracture'. The blackletter lines are broken up — that is, their forms contain many angles when compared to the smooth curves of the Antiqua (common) typefaces modeled after antique Roman square capitals and Carolingian minuscule. From this, Fraktur is sometimes contrasted with the "Latin alphabet" in northern European texts, despite simply being a typeface of that alphabet. Similarly, the term "Fraktur" is sometimes applied to all of the blackletter typefaces (known in German as Gebrochene Schrift).

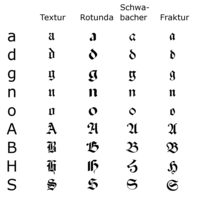

Characteristics

Besides the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet, the ß (Eszett [ɛsˈtsɛt]) and vowels with umlauts, Fraktur typefaces include the ſ (long s). They also sometimes include a variant form of the letter r known as the r rotunda, and a variety of ligatures once intended to aid the typesetter and which have specialized rules for their use. Most older Fraktur typefaces make no distinction between the majuscules "I" and "J" (where the common shape is more suggestive of a "J"), even though the minuscules "i" and "j" are differentiated.

One difference between the Fraktur and other blackletter scripts is that in the small-letter o, the left part of the bow is broken, but the right part is not. From at least the 16th century, Danish texts already generally employed ø in preference to the German and Swedish ö.[1]

Origin

The first Fraktur typeface was designed when Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I (c. 1493–1519) established a series of books and had a new typeface created specifically for this purpose, designed by Hieronymus Andreae. Fraktur quickly overtook the earlier Schwabacher and Textualis typefaces in popularity, and a wide variety of Fraktur fonts were carved.

Use

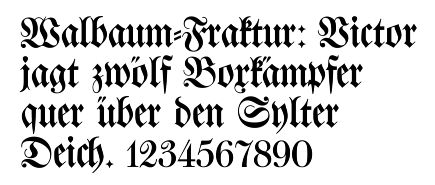

Typesetting in Fraktur was still very common in the early 20th century in all German-speaking countries and areas, as well as in Norway, Estonia, and Latvia, and was still used to a very small extent in Sweden, Finland and Denmark,[2] while other countries typeset in Antiqua in the early 20th century. Some books at that time used related blackletter fonts such as Schwabacher; however, the predominant typeface was the Normalfraktur (Fig. 1), which came in slight variations.

From the late 18th century to the late 19th century, fraktur was progressively replaced by antiqua as a symbol of the classicist age and emerging cosmopolitanism in most of the countries in Europe that had previously used fraktur. The debate surrounding this move was hotly discussed in Germany, where it was known as the Antiqua–Fraktur dispute. The shift affected mostly scientific writing in Germany, whereas most belletristic literature and newspapers continued to be printed in broken fonts. This radically changed when on January 3, 1941, Martin Bormann issued a circular to all public offices which declared Fraktur (and its corollary, the Sütterlin-based handwriting) to be Judenlettern (Jewish letters) and prohibited their further use. It has been speculated by German historian Albert Kapr that the régime had realized that Fraktur would inhibit communication in the territories occupied during World War II.[5] Fraktur saw a short resurgence after the War, but quickly disappeared in a Germany keen on modernising its appearance.

Fraktur is today used mostly for decorative typesetting; for example, a number of traditional German newspapers such as the Frankfurter Allgemeine, as well as the Norwegian Aftenposten, still print their name in Fraktur on the masthead, and it is also popular for pub signs and the like. In this modern decorative use, the Fraktur rules about the use of long s and short s and of ligatures are often disregarded.

Individual Fraktur letters appear frequently in mathematics, which often denotes associated or parallel concepts by a single letter in various fonts. For example, a Lie group is often denoted by G, while its associated Lie algebra is . A ring ideal might be named while an element is .

Fraktur in Unicode

In Unicode, Fraktur is considered a font of the Latin script, and is not encoded separately. The additional ligatures that are required for fraktur fonts will not be encoded in Unicode.[1] Instead, Unicode proposes to deal with these ligatures using smart-font technologies such as OpenType, AAT or Graphite. There are many fraktur fonts that do not use smart-font technologies but use their own legacy encoding instead that is not compliant with Unicode.

There are Fraktur symbols in the Unicode blocks of mathematical alphanumeric symbols and letterlike symbols. However, these are only meant to be used in mathematics.[2] Therefore, there are no letters such as ä, ö, ü, ß that are not used in mathematics.

Samples

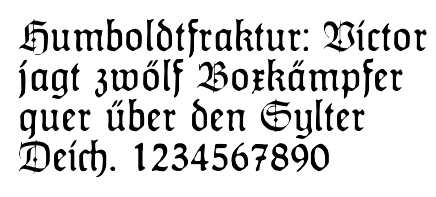

In these figures, the German sentence that appears after the names of the fonts (Walbaum-Fraktur in Fig. 1 and Humboldfraktur in Fig. 2) reads, "Victor jagt zwölf Boxkämpfer quer über den Sylter Deich". It means "Victor chases twelve boxers across the Sylt dike" and contains all 26 letters of the alphabet plus the umlauted glyphs used in German, making it an example of a pangram. Note that in the second specimen, the "t" in "Humboldt" is omitted.

See also

|

Further reading

- Bain, Peter and Paul Shaw. Blackletter: Type and National Identity. Princeton Architectural Press: 1998. ISBN 1-56898-125-2.

- Silvia Hartmann: Fraktur oder Antiqua. Der Schriftstreit von 1881 bis 1941, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main u. a. 1998 (2. üb. A. 1999), ISBN 978-3-631-35090-4

- Fiedl, Frederich, Nicholas Ott and Bernard Stein. Typography: An Encyclopedic Survey of Type Design and Techniques Through History. Black Dog & Leventhal: 1998. ISBN 1-57912-023-7.

- Macmillan, Neil. An A–Z of Type Designers. Yale University Press: 2006. ISBN 0-300-11151-7.

References

- ^ Cf., inter alia, Bibla: Det er den gantske Hellige Scifft: udsæt paa Danske. 1550. Template:Da-icon & Biblia: Det er Den gantske Hellige Scrifft paa Danske igien offuerseet oc prentet effter vor allernaadigste herris oc Kongis K. Christian den IV. Befaling. 1633. Template:Da-icon

- ^ In Denmark in 1902 the percentage of printed material using antiqua amounted to 95% according to R. Paulli, "Den sejrende antikva", i: Det trykte Ord, published by Grafisk Cirkel, Copenhagen, 1940.

- ^ R. Paulli, "Den sejrende antikva", i: Det trykte Ord, published by Grafisk Cirkel, Copenhagen, 1940.

- ^ Tore Rem, "Materielle variasjoner. Overgang fra fraktur til antikva i Norge." in: Mats Malm, Barbro Ståhle Sjönell & Petra Söderlund (eds.), Bokens materialitet - Bokhistoria och bibliografi, Svenska Vitterhetssamfundet, Stockholm, 2009

- ^ Albert Kapr, Fraktur: Form und Geschichte der gebrochenen Schriften, Mainz, 1993, p. 81.

External links

- A complete Fraktur chart

- Template:De icon Website of Dieter Steffmann, which has a large number of digitized Fraktur fonts

- Blackletter: Type and National Identity[dead link]

- Template:De icon Delbanco: German Purveyors of Fraktur fonts (commercial)

- Setting up Microsoft Windows NT, 2000 or Windows XP to support Unicode supplementary characters

- UniFraktur: Free Unicode-compliant Fraktur fonts and resources