Aureola

An aureola or aureole (diminutive of Latin aura, "air") is the radiance of luminous cloud which, in paintings of sacred personages, surrounds the whole figure. In the earliest periods of Christian art this splendour was confined to the figures of the persons of the Christian Godhead, but it was afterwards extended to the Virgin Mary and to several of the saints.

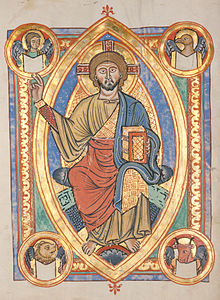

The aureola, when enveloping the whole body, generally appears oval or elliptical in form, but occasionally circular or quatrefoil. When it appears merely as a luminous disk round the head, it is called specifically a halo or nimbus, while the combination of nimbus and aureole is called a glory. The strict distinction between nimbus and aureole is not commonly maintained, and the latter term is most frequently used to denote the radiance round the heads of saints, angels or persons of the Christian Godhead.

This is not to be confused with the specific motif in art of the Infant Jesus appearing to be a source of light in a Nativity scene. These depictions derive directly from the accounts given by Saint Bridget of Sweden of her visions, in which she describes seeing this.

The nimbus in Christian art first appeared in the 5th century, but practically the same device was known several centuries earlier, in non-Christian art. It is found in some Persian representations of kings and gods, and appears on coins of the Kushan kings Kanishka, Huvishka and Vasudeva, as well as on most representations of the Buddha in Greco-Buddhist art from the 1st century AD. Its use has also been traced through the Egyptians to the Greeks and Romans, representations of Trajan (arch of Constantine) and Antoninus Pius (reverse of a medal) being found with it.

In the circular form the nimbus constitutes a natural and even primitive use of the idea of a crown, modified by an equally simple idea of the emanation of light from the head of a superior being, or by the meteorological phenomenon of a halo. The probability is that all later associations with the symbol refer back to an early astrological origin (compare Mithras), the person so glorified being identified with the sun and represented in the sun's image; so the aureole is the Hvareno of Mazdaism.[citation needed] From this early astrological use, the form of "glory" or "nimbus" has been adapted or inherited under new beliefs.

Mandorla

A Mandorla is an Vesica Piscis shaped aureola which surrounds the figures of Christ and the Virgin Mary in traditional Christian art. [citation needed] Examples may be seen in icons of the transfiguration and other imagery. The symbol is also used in non-Christian contexts. Mandorla means almond in Italian.

In a famous romanesque fresco of Christ in Glory at Sant Climent de Taüll the inscription "Ego Sum Lux Mundi" is incorporated in the design.[1]

The tympan at Conques has Christ, with one of those beautyful gestures carved in romanesque sculpture, indicate the angels at his feet bearing candlesticks. Six surrounding stars, resembling blossoming flowers, indicate the known planets including the moon. Here the symbolism implies Christ as the Sun. [2]

In one special case, at Cervon (Nièvre), Christ is seated surrounded by eight stars, resembling blossoming flowers. [3] At Conques the flowers are six-petalled. At Cervon, where the almond motif is repeated in the rim of the mandorla, they are five-petalled, as are almond flowers -the first flowers to appear at the end of winter, even before the leaves of the almond tree. Here one is tempted to seek for reference in the symbolism of the nine branched Chanukkiyah candelabrum. It should be remembered that in the XII century a great school of Judaic thought radiated from Narbonne, coinciding with the origins of the Kabbalah. (see Gershom Scholem). Furthermore, at Cervon the eight star/flower only is six petalled: the Root of David, the Morningstar, mentioned at the close of Book of Revelation (22:16) [4] ( In one of the oldest manuscripts of the complete Hebrew Bible, the Leningrad Codex, one finds the Star of David imbedded in an octagon )

In the symbolism of Hildegarde von Bingen the mandorla refers to the universe. [citation needed]

See also

References

- Timmers J.J.M. A Handbook of Romanesque Art New York London 1969 Icon Editions, Harper and Row

- Gérard de Champéaux, Dom Sébastièn Sterckx o.s.b. Symboles, introduction à la nuit des temps 3, Paris 1966 ed. Zodiaque (printed: Cum Permissu Superiorum)

- Brian Young The Villein's Bible; stories in romanesque carving London 1990 Barry & Jenkins

- Roger Cook The Tree of Life: Image for the Cosmos New York 1974 Avon Books

- Gershom Scholem Origins of the Kabbalah Princeton 1990 Princeton Paperback