Knock Me Down and Slavic dialects of Greece: Difference between pages

better wording |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox |

{{Infobox Language |

||

|name=Slavic dialects of Greece |

|||

| Name = Knock Me Down |

|||

|nativename= ''bălgarski'' / ''makedonski'' |

|||

| Cover = Knockmedown.jpg |

|||

|familycolor=Indo-European |

|||

| Artist = [[Red Hot Chili Peppers]] |

|||

|states=[[Greece]] |

|||

| from Album = [[Mother's Milk]] |

|||

|speakers=20,000 (2008)<ref name=autogenerated3>Στη Δυτική Μακεδονία, κυρίως στις περιοχές της Φλώρινας, της Καστοριάς, της Βέροιας και του Κιλκίς υπάρχουν άνθρωποι οι οποίοι μιλούν (και) μία διάλεκτο που ονομάζουν «μακεντόνσκι», κι έχει ομοιότητες με τη γλώσσα που μιλούν στην ΠΓΔΜ, η οποία, με τη σειρά της, έχει σαφώς βουλγαρικές καταβολές.</ref> - <br>41,017 (1951) - <br>230,000<ref>[http://www.lmp.ucla.edu/Profile.aspx?LangID=42&menu=004 UCLA Macedonian], [http://www.lmp.ucla.edu/Profile.aspx?LangID=37&menu=004 UCLA Bulgarian]</ref> |

|||

| B-side = "Millionaires Against Hunger"<br>"[[Show Me Your Soul]]" |

|||

|rank=not official |

|||

| Released = [[August 22]], [[1989]] |

|||

|fam2=[[Slavic languages|Slavic]] |

|||

| Recorded = 1989 |

|||

|fam3=[[South Slavic languages|South Slavic]] |

|||

| Genre = [[Funk rock]] |

|||

|fam4=[[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] / [[Macedonian language|Macedonian]] |

|||

| Length = 3:44 |

|||

|nation= |

|||

| Label = [[EMI]]/[[Capitol Records]] |

|||

|agency= |

|||

| Writer = [[Flea (musician)|Flea]]/[[Anthony Kiedis|Kiedis]]/[[Chad Smith|Smith]]/[[John Frusciante|Frusciante]] |

|||

|iso1= |

|||

| Producer = [[Michael Beinhorn]] |

|||

|iso2b=|iso2t= |

|||

| Last single = "[[Me and My Friends]]"<br/>([[1987]]) |

|||

|iso3= |

|||

| This single = "'''Knock Me Down'''"<br/>([[1989]]) |

|||

| Next single = "[[Higher Ground (song)#Red Hot Chili Peppers cover|Higher Ground]]"<br/>([[1989]]) |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{South Slavic languages sidebar}} |

|||

The '''Slavic dialects of Greece''' are the dialects of [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] or [[Macedonian language|Macedonian]] spoken by [[Minorities in Greece|minority groups]] in the regions of [[Macedonia (Greece)|Macedonia]] and [[Thrace (Greece)|Thrace]] in northern [[Greece]]. Linguistically, these dialects are classified as either [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] or [[Pomak]] in [[Western Thrace|Thrace]], transitional dialects in [[East Macedonia and Thrace|East Macedonia]], [[Macedonian language|Macedonian]] in [[Central Macedonia|Central]] and [[West Macedonia]]. Until the official codification of the [[Macedonian Language]] in 1944 many linguists considered the dialects to be apart of the [[Dialects of Bulgarian|Bulgarian Diasystem]], this has remained the predominant attitude in Bulgaria. |

|||

<ref> Шклифов, Благой. Проблеми на българската диалектна и историческа фонетика с оглед на македонските говори, София 1995, с. 14.</ref><ref>Шклифов, Благой. Речник на костурския говор, Българска диалектология, София 1977, с. кн. VІІІ, с. 201-205,</ref><ref>Mladenov, Stefan. Geschichte der bulgarischen Sprache, Berlin, Leipzig, 1929, § 207-209.</ref><ref>Mazon, Andre. Contes Slaves de la Macédoine Sud-Occidentale: Etude linguistique; textes et traduction; Notes de Folklore, Paris 1923, p. 4.</ref><ref>Селищев, Афанасий. Избранные труды, Москва 1968, с. 580-582.</ref><ref>Die Slaven in Griechenland von Max Vasmer. Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1941. Kap. VI: Allgemeines und sprachliche Stellung der Slaven Griechenlands, p.324.</ref> |

|||

==History== |

|||

"'''Knock Me Down'''" is a single from the [[Red Hot Chili Peppers]] album ''[[Mother's Milk]]''. |

|||

[[Slavic peoples|Slavic tribes]] began settling in the [[Macedonia (region)|region of Macedonia]] and [[Thrace]] in the 6th and 7th centuries and in the following centuries mixed with the local populations. During [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman rule]], most of the [[Eastern Orthodox Church|Orthodox]]-Slavic population of Macedonia had not formed a national identity separate from their neighbors and were instead identified through their religious affiliation. In the Middle Ages and later, until XX century the Slav-speaking population of Aegean Macedonia was indentified mostly as Bulgarian or Greek.<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&id=KF0GAAAAQAAJ&dq=Cousin%C3%A9ry+Voyage+dans+la+Mac%C3%A9doine&printsec=frontcover&source=web&ots=U_MQZRU5bp&sig=GfL8YVz6jzeJfA9rALydncpd2UU&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=4&ct=result#PPA15,M1 Cousinéry, Esprit Marie. Voyage dans la Macédoine: contenant des recherches sur l'histoire, la géographie, les antiquités de ce pay, Paris, 1831, Vol. II, p. 15-17], one of the passages in English - [http://history-of-macedonia.com/wordpress/2008/04/13/french-consul-in-1831-macedonia-consists-of-greeks-and-bulgarians/], [http://etd.lib.metu.edu.tr/upload/12606837/index.pdf Engin Deniz Tanir, The Mid-Nineteenth century Ottoman Bulgaria from the viewpoints of the French Travelers, A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University, 2005, p. 99, 142],[http://promacedonia.org/en/ban/nr1.html#4 Kaloudova, Yordanka. Documents on the situation of the population in the southwestern Bulgarian lands under Turkish rule, Военно-исторически сборник, 4, 1970, p. 72]</ref><ref>Pulcherius, Receuil des historiens des Croisades. Historiens orientaux. III, p. 331 – a passage in English -[http://promacedonia.org/en/ban/ma1.html#13, http://promacedonia.org/en/ban/nr1.html#4]</ref> |

|||

The Muslim Slavic-speakers in [[Western Thrace]] known as [[Pomak]] themselves self-identified predominantly as [[Turkish people|Turks]], because Turks and Pomaks were part of the same [[Millet (Ottoman Empire)|''millet'']] during the years of the [[Ottoman Empire]]. |

|||

<ref name="GHMPomaks">[http://www.greekhelsinki.gr/english/reports/pomaks.html Report on the Pomaks], by the [[International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights|Greek Helsinki Monitor]]</ref> After [[WWI]], new [[Slav Macedonian]] (Greek: Σλαβομακεδόνας) nationalism began to arise.<ref>[http://books.google.bg/books?id=j_NbmSoRsRcC&dq=who+are+the+macedonians&pg=PP1&ots=0Knkik_lzT&sig=BjXQx9sHrG4S-CqpgRV4QRhY_Cg&hl=bg&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result#PPA87,M1 Who Are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton Indiana UP, 2000 ISBN 0253213592. p. 85, The Interwar period - Greece. <!-- Citation: ...in common speech the Greek population referred to them as Bulgarians and the notion of them as a separate people, Macedonians, only came later...-->]</ref> In 1934 the [[Comintern]] issued a declaration supporting the development of Macedonian nationalism<ref>"Резолюция о македонской нации (принятой Балканском секретариате Коминтерна" - Февраль 1934 г, Москва</ref> However today the vast majority of this people espouse a Greek national identity and are bilingual in Greek. The fact that the majority of these people self-identify as Greeks makes their numbers uncertain. |

|||

==Self-Identification== |

|||

The song depicts a negativity towards the stereotypically egotistic lifestyle of your typical rockstar. The band's opposition is displayed through their lyrics: "If you see me getting mighty / If you see me getting high / Knock me down / I'm not bigger than life." |

|||

The linguistic affiliation of these varieties with either of the two neighbouring standard languages is a matter of some discussion, as is the ethnic affiliation of their speakers. Locally and in the [[Greek language]] they are often referred to simply as "Slavic" (σλάβικα ''slávika'') or "local" (εντόπια ''Entópia'', ''Dópia''). Among self-identifying terms, ''makedonski''{{fact|date=September 2008}} ("Macedonian"), ''bălgarski''<ref>:bg:s:Дописка от село Високо</ref> ("Bulgarian", ''balgàrtzki'' or ''bulgàrtski'' in the region of [[Kostur]]<ref>Шклифов, Благой and Екатерина Шклифова, Български деалектни текстове от Егейска Македония, София 2003, с. 28-33</ref>) and Pomatskou ("Pomak") are also used<ref>[http://www.us-english.org/foundation/research/olp/viewResearch.asp?CID=56&TID=6 U.S.ENGLISH Foundation Official Language Research - Greece: Language in everyday life<!--Bot-generated title-->]</ref> along with ''naši'' ("our own") and ''stariski'' ("old")<ref>http://books.google.com.au/books?id=JxCnAHCCuxYC&printsec=frontcover&dq=macedonians+in+greece&sig=67hHATiJ2xY16hXJ0c8Z3zrX5C8</ref>. In 2008, the Elefterotipia newspaper stated that there are 20,000 people in Greece, speaking a dialect of Bulgarian origin.<ref name=autogenerated3>Στη Δυτική Μακεδονία, κυρίως στις περιοχές της Φλώρινας, της Καστοριάς, της Βέροιας και του Κιλκίς υπάρχουν άνθρωποι οι οποίοι μιλούν (και) μία διάλεκτο που ονομάζουν «μακεντόνσκι», κι έχει ομοιότητες με τη γλώσσα που μιλούν στην ΠΓΔΜ, η οποία, με τη σειρά της, έχει σαφώς βουλγαρικές καταβολές.</ref> |

|||

The lyrics are written in reference to the popular saying, "high and mighty." |

|||

== Linguistic Opinions == |

|||

[[Anthony Kiedis]] and [[John Frusciante]] sing all the lyrics simultaneously, but the record label edit of the song is mixed in such a way that Frusciante's vocals are set louder than Kiedis' throughout the song. The original, longer version of this song is featured on the bonus ''Mother's Milk'' CD, which contains additional verses and an extended bridge. In this version, Kiedis' vocals are more prominent. |

|||

According to [[Peter Trudgill]], |

|||

<blockquote> |

|||

"Knock Me Down" is featured in the music video game ''[[Guitar Hero: On Tour]]'' for [[Nintendo DS]]. |

|||

There is, of course, the very interesting [[Ausbausprache - Abstandsprache - Dachsprache|Ausbau]] sociolinguistic question as to whether the language they speak is [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] or [[Macedonian language|Macedonian]], given that both these languages have developed out of the [[South Slavic languages|South Slavonic]] [[dialect continuum]] that embraces also [[Serbian language|Serbian]], [[Croatian language|Croatian]], and [[Slovenian language|Slovene]]. In former Yugoslav Macedonia and Bulgaria there is no problem, of course. Bulgarians are considered to speak Bulgarian and Macedonians Macedonian. The Slavonic dialects of Greece, however, are "roofless" dialects whose speakers have no access to education in the standard languages. Greek non-linguists, when they acknowledge the existence of these dialects at all, frequently refer to them by the label ''Slavika'', which has the implication of denying that they have any connection with the languages of the neighboring countries. It seems most sensible, in fact, to refer to the language of the Pomaks as Bulgarian and to that of the Christian Slavonic-speakers in Greek Macedonia as Macedonian.<ref>Trudgill P., 2000, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity". In: Stephen Barbour and Cathie Carmichael (eds.), ''Language and Nationalism in Europe'', Oxford : Oxford University Press, p.259.</ref> |

|||

</blockquote> |

|||

According to Roland Schmieger, |

|||

==Music video== |

|||

The video <ref>[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hU9vToZ8ti4]</ref> featured actor [[Alex Winter|Alex Winter]], and was directed by Drew Carolan, who also directed the video for "[[Higher Ground (song)|Higher Ground]]." |

|||

<blockquote> |

|||

==Track Listings== |

|||

Apart from certain peripheral areas in the far east of Greek Macedonia, which in our opinion must be considered as part of the Bulgarian linguistic area (the region around Kavala and in the Rhodope Mountains, as well as the eastern part of Drama ''nomos''), the dialects of the Slav minority in Greece belong to Macedonia [[diasystem]].<ref>Schmieger, R. 1998. "The situation of the Macedonian language in Greece: sociolinguistic analysis", ''International Journal of the Sociology of Language'' 131, 125-55.</ref> |

|||

CD single (1989) |

|||

</blockquote> |

|||

# "Knock Me Down" – 3:44 |

|||

# "Millionaires Against Hunger" (Previously Unreleased) – 3:28 |

|||

# "[[Fire (Jimi Hendrix song)|Fire]]" – 2:03 |

|||

==Classification and Dialects== |

|||

CD version 2 and 12" single (1989) |

|||

# "Knock Me Down" – 3:44 |

|||

# "Punk Rock Classic" – 1:47 |

|||

# "Magic Johnson" – 2:57 |

|||

# "Special Secret Song Inside" – 3:16 |

|||

It is generally accepted that both [[Macedonian language|Macedonian]] and [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] are both spoken in the north of [[Greece]]. They are split into three major groups: [[Dialects of the Macedonian language|Macedonian]], transitional dialects, and [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]]. This opinion is not accepted by authors who consider all of these dialects as a part of Western or Eastern [[Bulgarian dialects]].<ref name="Stoykov">Stoyko Stoykov. ''Bulgarian Dialectology''. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Publishing House, 4th Edition, Sofia, 2002, pp. 170-186</ref> |

|||

7" single (1989) |

|||

# "Knock Me Down" – 3:44 |

|||

# "Punk Rock Classic" – 1:47 |

|||

# "Pretty Little Ditty" – 1:37 |

|||

===Macedonian Language=== |

|||

7" version 2 (1989) |

|||

{{see|Dialects of the Macedonian language}} |

|||

# "Knock Me Down" – 3:44 |

|||

[[Image:Mergedcopy.svg|200px|left|thumb|Distribution of the Macedonian language according to the ''Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups'']] |

|||

# "Punk Rock Classic" – 1:47 |

|||

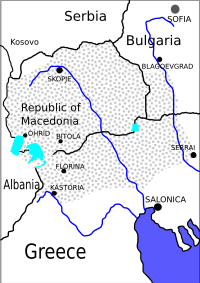

[[Image:Macedonian Slavic dialects.png|250px|thumb|left|A map showing the various Slavic dialects as spoken in Greece.]] |

|||

# "Pretty Little Ditty" – 1:37 |

|||

Various dialects of the [[Macedonian Language]] are spoken in the Peripheries of [[West Macedonia|West]] and [[Central Macedonia]]<ref>стр.247 Граматика на македонскиот литературен јазик, Блаже Конески, Култура- Скопје 1967 </ref>. The [[Dialects of the Macedonian language]] spoken in [[Greece]] include the [[Upper Prespa dialect|Upper]] and [[Lower Prespa dialect]]s, the [[Kostur Dialect|Kastoria Dialect]]<ref>[[:bg:s:Дописка от село Бобища]]</ref>, the [[Nestram-Kostenar dialect]], the [[Florina]] variant of the [[Prilep-Bitola dialect]] and the [[Solun-Voden dialect|Salonica-Edessa Dialect]].<ref>Topolinjska, Z. (1998). "In place of a foreword: facts about the Republic of Macedonia and the Macedonian language" in International Journal of the Sociology of Language. Issue 131</ref> Certain characteristics of the these dialects include the changing of the suffix '''ovi''' to '''oj''' creating the words '''лебови> лебој''' (lebovi> leboj/ bread).<ref>стр. 244 Македонски јазик за средното образование- Стојка Бојковска, Димитар Пандев, Лилјана Минова-Ѓуркова, Живко Цветковски- Просветно дело- Скопје 2001 </ref> Often the intervocalic consonants of /v/, /g/ and /d/ are often lost, changing words from polovina >polojna (a half) and sega > sea (now).<ref>Friedman, V. (2001) Macedonian (SEELRC) </ref> In other Phonological and Morphological Characteristics they remain similar to the other South-Eastern dialects spoken in the [[Republic of Macedonia]] and [[Albania]].<ref>Poulton, Hugh. (1995). Who Are the Macedonians?, (London: C. Hurst & Co. Ltd:107-108.). </ref> |

|||

===Transitional Dialects=== |

|||

7" version 3 (1989) |

|||

# "Knock Me Down" – 3:44 |

|||

# "[[Show Me Your Soul]]" (Previously Unreleased) – 4:22 |

|||

The [[Ser-Drama-Lagadin-Nevrokop dialect]] is considered a transitional dialects between [[Macedonian Language|Macedonian]] and [[Bulgarian Language|Bulgarian]] in Macedonian dialectology. In Bulgarian dialectology, [[Ser-Drama-Lagadin-Nevrokop dialect|Drama-Ser dialect]] and [[Solun dialect]] are considered Eastern Bulgarian dialects which are transitory between the Western and Eastern [[Bulgarian dialects]] and are grouped as West-Rupian dialects, part of the large Rupian dialect massif of Rhodopes and Thrace .<ref name="Stoykov" /> They are spoken in the peripheral region of [[East Macedonia]] along with a small population in [[Bulgaria]]<ref>Z. Topolińska- B. Vidoeski, Polski~macedonski- gramatyka konfrontatiwna, z.1, PAN, 1984 </ref>. The [[Bulgarian Language|Bulgarian]] vowels of я /ja/ and Й /ji/ are kept, transforming words such as николаи/nikolai into николай/nikolaĭ and Кои/Koj into Кой/Koĭ. Macedonian and Western Bulgarian words like Бел/Bel convert to the Eastern Bulgarian form of бял /bʲal/ (white).<ref>Friedman, V. (1998) "The implementation of standard Macedonian: problems and results" in International Journal of the Sociology of Language. Issue 131</ref> Old Church Slavonic ръ/рь and лъ/ль are pronounced as {{IPA|ər}} and {{IPA|əl}}, respectively (cf. ръ/ър ({{IPA|rə}}/{{IPA|ər}}) and лъ/ъл ({{IPA|lə}}/{{IPA|əl}}) in [[Bulgarian language|Standard Bulgarian]] and vocalic r/oл ({{IPA|ɔl}}) in [[Macedonian language|Standard Macedonian]])<ref name=autogenerated1>{{cite book |

|||

7" version 4 (1989) |

|||

|last=Sussex |

|||

# "Knock Me Down" – 3:44 |

|||

|first=Roland |

|||

# "Punk Rock Classic" – 1:47 |

|||

|coauthors=Paul Cubberley |

|||

# "Magic Johnson" – 2:57 |

|||

|title=The Slavic Languages |

|||

# "Special Secret Song Inside" – 3:16 |

|||

|publisher=Cambridge University Press |

|||

|date=2006 |

|||

|pages=p.509 |

|||

|isbn=0521223156 }}</ref><ref name="Stoykov" />. Likewise, Old Church Slavonic [[yus]] and ъ are both pronounced with the [[schwa]] ({{IPA|ə}}) as in Bulgarian, rather than as {{IPA|a}} and {{IPA|ɔ}}, respectively, as in Macedonian<ref name=autogenerated1 />. The sound х/h also adopts the Bulgarian pronunciation of х/kh. The dialect's also have many similarities to both the [[Bulgarian Language|Bulgarian]] and [[Macedonian Language|Macedonian]] diasystems are often placed in both.<ref> Trudgill P., 2000, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity". In: Stephen Barbour and Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford : Oxford University Press</ref> |

|||

===Bulgarian language and the Pomak Dialects=== |

|||

12" single (1989) |

|||

{{see|Bulgarian dialects}} |

|||

# "Knock Me Down" – 3:44 |

|||

[[Image:Bgmap yat.png|right|300px|thumb|The ''[[Yat]]'' split in the [[Bulgarian Language]].]] |

|||

# "Millionaires Against Hunger" (Previously Unreleased) – 3:28 |

|||

The [[Bulgarian Language]] is used in [[Western Thrace]]. In Greece it is called the "Pomak language" or the "Pomak dialects". The Pomak dialects are mainly spoken and taught at primary school level in the [[Pomak]] regions of Greece, which are primarily in the [[Rhodope Mountains]]. The language in Greek is known as 'Pomatskou' and taught in the Greek alphabet. The main school manual is 'Pomaktsou' by Moimin Aidin and Omer Hamdi, Komotini 1997. There is also a Pomak-Greek dictionary by Ritvan Karahodja, 1996. The number of Pomaks ranges from 30,000 to 90,000 whose presence dates from the days of the Byzantine empire. It is used by many of the Pomak speakers on either side of the Bulgarian-Greek border. The dialects are on the '''jat''' side of the Bulgarian split yet many pockets of '''e''' speakers remain. The standard Bulgarian language is not taught in Greece. |

|||

# "[[Fire (Hendrix song)|Fire]]" – 2:03 |

|||

# "Punk Rock Classic" – 1:47 |

|||

Many Greek linguists do not classify the Slavic languages spoken in [[Greece]] to be part of any diasystem or any particular Language.<ref>Trudgill, P. (1992) "Ausbau sociolinguistics and the perception of language status in contemporary Europe" in International Journal of Applied Linguistics. Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 167-177 </ref> |

|||

{{Red Hot Chili Peppers}} |

|||

== Usage of Slavic Languages in Greece == |

|||

[[Category:Red Hot Chili Peppers songs]] |

|||

[[Category:1989 songs]] |

|||

[[Category:1989 singles]] |

|||

The use of any [[Slavic language]] in the area now known as [[Greece]] has been prominent since the invasion of [[Slavic peoples#Slavic migrations|Slavic tribes]] in the 5th and 6th centuries. Although some [[Slavs]] were [[Hellenization|Hellenized]] or assimilated over time, many especially in the north of the country were not. As languages were codified in the 19th and 20th century many people began to identify their language as [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] and later [[Macedonian language|Macedonian]]. After the Balkan wars many Slavs from [[Greek Macedonia]] who identified as [[Bulgarians]] left [[Greece]] for [[Bulgaria]]<ref>Human Rights Watch |

|||

{{1980s-rock-song-stub}} |

|||

</ref>. After the [[Second World War]] many [[Macedonian Language]] speakers also left [[Greece]]. The 1951 Greek Census reported c.40,000 people who declared their mother language to be Slavic or Slav-Macedonian<ref>[http://www.usefoundation.org/foundation/research/olp/viewResearch.asp?CID=56&TID=6 U.S.ENGLISH Foundation Official Language Research - Greece: Language in everyday life<!--Bot-generated title-->]</ref>. Since then no Greek census has asked questions regarding mother language. |

|||

===Distribution=== |

|||

[[es:Knock Me Down]] |

|||

[[Image:Greece linguistic minorities.svg|thumb|right|200px|Traditional non-Greek languages zones in Greece. ''Note'': Greek is the dominant language throughout Greece; inclusion in a non-Greek language zone does not necessarily imply that the relevant minority language is still spoken there.<ref>See Ethnologue ([http://www.ethnologue.com/show_map.asp?name=MK&seq=10]); Euromosaic, ''Le (slavo)macédonien / bulgare en Grèce'', ''L'arvanite / albanais en Grèce'', ''Le valaque/aromoune-aroumane en Grèce'', and Mercator-Education: European Network for Regional or Minority Languages and Education, ''The Turkish language in education in Greece''. cf. also P. Trudgill, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity", in S Barbour, C Carmichael (eds.), ''Language and nationalism in Europe'', Oxford University Press 2000.</ref>]] |

|||

[[fr:Knock Me Down]] |

|||

The Distribution of the [[Macedonian language]] and [[Bulgarian language]] in [[Greece]] varies widely. Much of the population is concentrated in the [[Prefectures of Greece|Greek prefectures]] of [[Florina Prefecture|Florina]], [[Kastoria Prefecture|Kastoria]], [[Pella Prefecture|Pella]], [[Kilkis Prefecture]] and [[Imathia Prefecture|Imathia]]. With a smaller [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] speaking population in [[East Macedonia and Thrace|Thrace]]. Their has never been a large Slavic speaking population in the [[Chalcidice]], [[Pieria]] and the [[Kavala Prefecture]]<ref>Minority Rights Group,''Minorities in the Balkans'', page 75.</ref> |

|||

[[it:Knock Me Down]] |

|||

[[pl:Knock Me Down]] |

|||

===Population Estimates=== |

|||

[[fi:Knock Me Down]] |

|||

The exact numbers of speakers in Greece is hard to ascertain. Jacques Bacid estimates in his book that "over 200,000<sup>1</sup> Macedonian speakers remained in Greece"<ref>Jacques Bacid, Ph.D. Macedonia Through the Ages. Columbia University, 1983.</ref>. Other sources put the numbers of speakers at 180,000<sup>2</sup><ref>[http://www.geocities.com/Athens/9479/makedonia.html GeoNative - Macedonia<!--Bot-generated title-->]</ref><ref>L. M. Danforth, The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World 1995, Princeton University Press</ref>, 220,000<sup>1</sup><ref>Hill, P. (1999) "Macedonians in Greece and Albania: A Comparative study of recent developments". Nationalities Papers Volume 27, 1 March 1999, page 44(14)</ref> 250,000<ref>[Macedonia and Greece - The Struggle to Define a New Balkan Nation Macedonia and Greece - The Struggle to Define a New Balkan Nation, John Shea]</ref>and 300,000<ref>Poulton, H.(2000), "Who are the Macedonians?",C. Hurst & Co. Publishers</ref>.The Encyclopedia Brittanica<ref>http://www.britannica.com/new-multimedia/pdf/wordat077.pdf</ref><sup>2</sup> and the Reader's Digest World Guide<sup>1</sup>. both put the figure of [[Ethnic Macedonians]] in [[Greece]] at 1.8% or c.200,000 people, they put the figure for [[Pomaks]] at .9% or c.100,000 people, with the native language roughly corresponding with the figures. The UCLA also states that there is 200,000 [[Macedonian language|Macedonian]] speakers in [[Greece]] and 30,000 [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] speakers.<ref>[http://www.lmp.ucla.edu/Profile.aspx?LangID=42&menu=004 UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile<!--Bot-generated title-->]</ref><ref>[http://www.lmp.ucla.edu/Profile.aspx?LangID=37&menu=004 UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile<!--Bot-generated title-->]</ref>. The European Commission on language states no official number but acknkowledges that the languages ([[Macedonian language|Macedonian]] and [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]]) spoken number into the hundreds of thousands.<sup>1</sup><ref>[http://ec.europa.eu/index_en.htm European Commission<!--Bot-generated title-->]</ref> |

|||

[[sv:Knock Me Down]] |

|||

<sup>1</sup> This refers to speakers regardless of Ethnic identity. |

|||

<sup>2</sup> No information is given regarding how the figures were obtained. |

|||

== Education == |

|||

[[Image:Abecedar.JPG|thumb|left|A Slavic language [[Abecedar]] schoolbook.]] |

|||

[[Image:Distribution of Races on the Balkans in 1922 Hammond.png|thumb|200px|Distribution of races in the Balkan Peninsula and Asia Minor in 1922, Racial Map Of Europe by Hammond & Co. "Macedonian Slavs" shown as Bulgarians and Serbs]] |

|||

[[Image:Hellenism in the Near East 1918.jpg|thumb|Right|200px|Greek ethnographic map of south-eastern Balkans, showing the Macedonian Slavs as a separate people, by Professor George Soteriadis, Edward Stanford, London, 1918.]] |

|||

Under the [[Treaty of Sèvres]] in 1920 (which was never ratified [http://www2.mfa.gr/NR/rdonlyres/3E053BC1-EB11-404A-BA3E-A4B861C647EC/0/1923_lausanne_treaty.doc]), Greece undertook the obligation to open schools for minority-language children. In 1925 the government of Greece submitted copies of a schoolbook called [[Abecedar]], which was written in the Slavic language for the Slavophone children and published by the Greek Ministry of Education, to the [[League of Nations]] as evidence that they were carrying out these obligations. [[Abecedar]] was written in a newly adapted variety of the [[Latin alphabet]] for the Slavic language in Greece, and not in the [[Cyrillic alphabet]] which was the official alphabet of neighboring [[Bulgaria]] and [[Serbia]] |

|||

- this also shows the intent of the Greek government to create a distinctively Slavic minority, not a Bulgarian or Serbian minority; the result being that Bulgaria and Serbia would have no right to interfere in Greece's internal affairs. |

|||

In October 2006 [http://florina.org/html/2006/abecedar.html] [http://florina.org/html/2006/abecedar_vinozhito_gr.html] [http://florina.org/html/abecedar/main.html], the [[Rainbow (political party)|Rainbow Party]] in Greece reprinted the original [[Abecedar]] Slavic language primer in [[Thessaloníki]], Greece, which was printed in [[Athens]] in 1925 and was based on the [[Florina|Florina/Lerin]] dialect, as well as an up to date primer in the standardized [[Macedonian language]] and [[Macedonian alphabet|script]] as taught in the [[Republic of Macedonia]] and presented it to the Greek Ambassador to the OSCE, Mr Manesis [http://florina.org/html/2006/macedonian_language_primer.html] [http://florina.org/html/2006/macedonian_language_primer_gr.html]. The book is being distributed to people who identify as [[Macedonian language|Macedonian]] speakers in northern Greece and it has been successfully promoted in the city of [[Thessaloníki]] [http://florina.org/html/2006/presentation_of_abecedar_in_solun.html]. |

|||

At present there is no formal teaching of this language within [[Greece]]<ref name=autogenerated2>[http://dev.eurac.edu:8085/mugs2/do/blob.html?type=html&serial=1044526702223 Greek Helsinki Monitor (Ghm) &<!--Bot-generated title-->]</ref> but it is possible to attain a private tutor. The language is used primarily in the home and within informal situations.<ref name=autogenerated2 />. |

|||

== The Metaxas regime == |

|||

On the [[August 4|4th August]] 1936 the [[Authoritarianism|authoritarian]] [[4th of August Regime|regime]] of General [[Ioannis Metaxas|Metaxas]] came to power, and a new state sponsored policy of [[Hellenisation]] was enacted. The aim was to Hellenise all the non-Greek speaking Orthodox Christian populations within the Greek state's territory; other Balkan countries ([[Serbia]], [[Bulgaria]], [[Romania]] and [[Albania]]) respectively followed similar policies. In Greece, the ensuing result left the Slavic speakers (and other minority speech communities) forcibly suppressed, and their privileges under the Treaty of Sèvres withdrawn. Policies of the Metaxas regime included forcible Hellenization of Personal and Surnames, Punishment for speaking a non-Greek language and changing of all Slavic toponyms<ref name=autogenerated2 /><ref>[http://www.uoc.es/euromosaic/web/document/macedoni/fr/i1/i1.html Denying Ethnic Identity, The Macedonians of Greece]</ref>. |

|||

== Present situation == |

|||

At present, the number of [[Minorities in Greece#Slavic-speaking|Slavophones]] in Greece is unknown. In the latest census posing a question on mother tongue (1951), 41,017 people declared themselves speakers of Slavic. Almost all Slavic speakers today in [[Macedonia (Greece)|Greek Macedonia]] also speak [[Greek language|Greek]]{{Fact|date=April 2008}} and most regard themselves as ethnically and culturally Greek{{Fact|date=September 2008}}. Many of those for whom a non-Greek identity was particularly important have tended to leave Greece during the past eighty years{{Fact|date=April 2008}}. Very few speakers can understand written Macedonian and Bulgarian and according to Euromosaic, the dialects spoken in Greece are mutually intelligible<ref>[http://www.uoc.es/euromosaic/web/document/macedoni/fr/i1/i1.html Euromosaic - Le [slavo]macédonien / bulgare en Grèce<!--Bot-generated title-->]</ref> as is the case with the [[Macedonian language|Macedonian]] and [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] languages. Some linguists used the term "Greek-Slavic" instead of the confusing interchangable terms "Macedonian" and "Bulgarian". |

|||

==Political Representation== |

|||

A political party that promotes the concept and rights of the "[[Macedonians (ethnic group)|Macedonian]] minority in Greece", and refers to the Slavic language as [[Macedonian language|Macedonian]] - the [[Rainbow (political party)|Rainbow Party]] (Ουράνιο Τόξο) - was founded in September 1998, and received 2,955 votes in the region of [[Macedonia (Greece)|Macedonia]] in the 2004 elections. Rainbow didn't participate in the [[Greek legislative election, 2007]] citing financial reasons<ref>[http://www.florina.org/html/2007/2007_efa_rainbow_elections_gr.html Press release of Rainbow]</ref>.Similarly, a pro-Bulgarian political website, known as [[Bulgarian Human Rights in Macedonia]] (Βουλγαρικά Ανθρώπινα Δικαιώματα στη Μακεδονία) was founded in June 2000, promoting the concept and rights of what they describe as the "[[Bulgarians|Bulgarian]] minority in Greece", and prefers to designate the local Slavic language as [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]]. Currently this political party operates only a website. |

|||

== See also == |

|||

* [[Greece]] |

|||

* [[Aegean Macedonians]] |

|||

* [[Macedonia (Greece)]] |

|||

* [[Bulgarian language]] |

|||

* [[Macedonian language]] |

|||

* [[Bulgarians]] |

|||

* [[Macedonians (ethnic group)]] |

|||

* [[Minorities in Greece#Slavic-speaking|Slavic speaking minority of Greece]] |

|||

* [[Slavic peoples]] |

|||

* [[Slavic languages]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

<div class="references-small" style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> |

|||

<references /> |

|||

</div> |

|||

== Bibliography == |

|||

*[[Peter Trudgill|Trudgill P.]] (2000) "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity" in ''Language and Nationalism in Europe'' (Oxford : Oxford University Press) |

|||

* Iakovos D. Michailidis (1996) "Minority Rights and Educational Problems in Greek Interwar Macedonia: The Case of the Primer 'Abecedar'". Journal of Modern Greek Studies'' 14.2 329-343 [http://www.macedonian-heritage.gr/downloads/library/Michai01.pdf] |

|||

{{Slavic languages}} |

|||

[[Category:Slavic languages]] |

|||

[[Category:Languages of Greece]] |

|||

[[de:Ägäis-Mazedonische Sprache]] |

|||

Revision as of 02:10, 11 October 2008

| Slavic dialects of Greece | |

|---|---|

| bălgarski / makedonski | |

| Native to | Greece |

Native speakers | 20,000 (2008)[1] - 41,017 (1951) - 230,000[2] |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| South Slavic languages and dialects |

|---|

The Slavic dialects of Greece are the dialects of Bulgarian or Macedonian spoken by minority groups in the regions of Macedonia and Thrace in northern Greece. Linguistically, these dialects are classified as either Bulgarian or Pomak in Thrace, transitional dialects in East Macedonia, Macedonian in Central and West Macedonia. Until the official codification of the Macedonian Language in 1944 many linguists considered the dialects to be apart of the Bulgarian Diasystem, this has remained the predominant attitude in Bulgaria. [3][4][5][6][7][8]

History

Slavic tribes began settling in the region of Macedonia and Thrace in the 6th and 7th centuries and in the following centuries mixed with the local populations. During Ottoman rule, most of the Orthodox-Slavic population of Macedonia had not formed a national identity separate from their neighbors and were instead identified through their religious affiliation. In the Middle Ages and later, until XX century the Slav-speaking population of Aegean Macedonia was indentified mostly as Bulgarian or Greek.[9][10] The Muslim Slavic-speakers in Western Thrace known as Pomak themselves self-identified predominantly as Turks, because Turks and Pomaks were part of the same millet during the years of the Ottoman Empire. [11] After WWI, new Slav Macedonian (Greek: Σλαβομακεδόνας) nationalism began to arise.[12] In 1934 the Comintern issued a declaration supporting the development of Macedonian nationalism[13] However today the vast majority of this people espouse a Greek national identity and are bilingual in Greek. The fact that the majority of these people self-identify as Greeks makes their numbers uncertain.

Self-Identification

The linguistic affiliation of these varieties with either of the two neighbouring standard languages is a matter of some discussion, as is the ethnic affiliation of their speakers. Locally and in the Greek language they are often referred to simply as "Slavic" (σλάβικα slávika) or "local" (εντόπια Entópia, Dópia). Among self-identifying terms, makedonski[citation needed] ("Macedonian"), bălgarski[14] ("Bulgarian", balgàrtzki or bulgàrtski in the region of Kostur[15]) and Pomatskou ("Pomak") are also used[16] along with naši ("our own") and stariski ("old")[17]. In 2008, the Elefterotipia newspaper stated that there are 20,000 people in Greece, speaking a dialect of Bulgarian origin.[1]

Linguistic Opinions

According to Peter Trudgill,

There is, of course, the very interesting Ausbau sociolinguistic question as to whether the language they speak is Bulgarian or Macedonian, given that both these languages have developed out of the South Slavonic dialect continuum that embraces also Serbian, Croatian, and Slovene. In former Yugoslav Macedonia and Bulgaria there is no problem, of course. Bulgarians are considered to speak Bulgarian and Macedonians Macedonian. The Slavonic dialects of Greece, however, are "roofless" dialects whose speakers have no access to education in the standard languages. Greek non-linguists, when they acknowledge the existence of these dialects at all, frequently refer to them by the label Slavika, which has the implication of denying that they have any connection with the languages of the neighboring countries. It seems most sensible, in fact, to refer to the language of the Pomaks as Bulgarian and to that of the Christian Slavonic-speakers in Greek Macedonia as Macedonian.[18]

According to Roland Schmieger,

Apart from certain peripheral areas in the far east of Greek Macedonia, which in our opinion must be considered as part of the Bulgarian linguistic area (the region around Kavala and in the Rhodope Mountains, as well as the eastern part of Drama nomos), the dialects of the Slav minority in Greece belong to Macedonia diasystem.[19]

Classification and Dialects

It is generally accepted that both Macedonian and Bulgarian are both spoken in the north of Greece. They are split into three major groups: Macedonian, transitional dialects, and Bulgarian. This opinion is not accepted by authors who consider all of these dialects as a part of Western or Eastern Bulgarian dialects.[20]

Macedonian Language

Various dialects of the Macedonian Language are spoken in the Peripheries of West and Central Macedonia[21]. The Dialects of the Macedonian language spoken in Greece include the Upper and Lower Prespa dialects, the Kastoria Dialect[22], the Nestram-Kostenar dialect, the Florina variant of the Prilep-Bitola dialect and the Salonica-Edessa Dialect.[23] Certain characteristics of the these dialects include the changing of the suffix ovi to oj creating the words лебови> лебој (lebovi> leboj/ bread).[24] Often the intervocalic consonants of /v/, /g/ and /d/ are often lost, changing words from polovina >polojna (a half) and sega > sea (now).[25] In other Phonological and Morphological Characteristics they remain similar to the other South-Eastern dialects spoken in the Republic of Macedonia and Albania.[26]

Transitional Dialects

The Ser-Drama-Lagadin-Nevrokop dialect is considered a transitional dialects between Macedonian and Bulgarian in Macedonian dialectology. In Bulgarian dialectology, Drama-Ser dialect and Solun dialect are considered Eastern Bulgarian dialects which are transitory between the Western and Eastern Bulgarian dialects and are grouped as West-Rupian dialects, part of the large Rupian dialect massif of Rhodopes and Thrace .[20] They are spoken in the peripheral region of East Macedonia along with a small population in Bulgaria[27]. The Bulgarian vowels of я /ja/ and Й /ji/ are kept, transforming words such as николаи/nikolai into николай/nikolaĭ and Кои/Koj into Кой/Koĭ. Macedonian and Western Bulgarian words like Бел/Bel convert to the Eastern Bulgarian form of бял /bʲal/ (white).[28] Old Church Slavonic ръ/рь and лъ/ль are pronounced as ər and əl, respectively (cf. ръ/ър (rə/ər) and лъ/ъл (lə/əl) in Standard Bulgarian and vocalic r/oл (ɔl) in Standard Macedonian)[29][20]. Likewise, Old Church Slavonic yus and ъ are both pronounced with the schwa (ə) as in Bulgarian, rather than as a and ɔ, respectively, as in Macedonian[29]. The sound х/h also adopts the Bulgarian pronunciation of х/kh. The dialect's also have many similarities to both the Bulgarian and Macedonian diasystems are often placed in both.[30]

Bulgarian language and the Pomak Dialects

The Bulgarian Language is used in Western Thrace. In Greece it is called the "Pomak language" or the "Pomak dialects". The Pomak dialects are mainly spoken and taught at primary school level in the Pomak regions of Greece, which are primarily in the Rhodope Mountains. The language in Greek is known as 'Pomatskou' and taught in the Greek alphabet. The main school manual is 'Pomaktsou' by Moimin Aidin and Omer Hamdi, Komotini 1997. There is also a Pomak-Greek dictionary by Ritvan Karahodja, 1996. The number of Pomaks ranges from 30,000 to 90,000 whose presence dates from the days of the Byzantine empire. It is used by many of the Pomak speakers on either side of the Bulgarian-Greek border. The dialects are on the jat side of the Bulgarian split yet many pockets of e speakers remain. The standard Bulgarian language is not taught in Greece.

Many Greek linguists do not classify the Slavic languages spoken in Greece to be part of any diasystem or any particular Language.[31]

Usage of Slavic Languages in Greece

The use of any Slavic language in the area now known as Greece has been prominent since the invasion of Slavic tribes in the 5th and 6th centuries. Although some Slavs were Hellenized or assimilated over time, many especially in the north of the country were not. As languages were codified in the 19th and 20th century many people began to identify their language as Bulgarian and later Macedonian. After the Balkan wars many Slavs from Greek Macedonia who identified as Bulgarians left Greece for Bulgaria[32]. After the Second World War many Macedonian Language speakers also left Greece. The 1951 Greek Census reported c.40,000 people who declared their mother language to be Slavic or Slav-Macedonian[33]. Since then no Greek census has asked questions regarding mother language.

Distribution

The Distribution of the Macedonian language and Bulgarian language in Greece varies widely. Much of the population is concentrated in the Greek prefectures of Florina, Kastoria, Pella, Kilkis Prefecture and Imathia. With a smaller Bulgarian speaking population in Thrace. Their has never been a large Slavic speaking population in the Chalcidice, Pieria and the Kavala Prefecture[35]

Population Estimates

The exact numbers of speakers in Greece is hard to ascertain. Jacques Bacid estimates in his book that "over 200,0001 Macedonian speakers remained in Greece"[36]. Other sources put the numbers of speakers at 180,0002[37][38], 220,0001[39] 250,000[40]and 300,000[41].The Encyclopedia Brittanica[42]2 and the Reader's Digest World Guide1. both put the figure of Ethnic Macedonians in Greece at 1.8% or c.200,000 people, they put the figure for Pomaks at .9% or c.100,000 people, with the native language roughly corresponding with the figures. The UCLA also states that there is 200,000 Macedonian speakers in Greece and 30,000 Bulgarian speakers.[43][44]. The European Commission on language states no official number but acknkowledges that the languages (Macedonian and Bulgarian) spoken number into the hundreds of thousands.1[45]

1 This refers to speakers regardless of Ethnic identity. 2 No information is given regarding how the figures were obtained.

Education

Under the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920 (which was never ratified [3]), Greece undertook the obligation to open schools for minority-language children. In 1925 the government of Greece submitted copies of a schoolbook called Abecedar, which was written in the Slavic language for the Slavophone children and published by the Greek Ministry of Education, to the League of Nations as evidence that they were carrying out these obligations. Abecedar was written in a newly adapted variety of the Latin alphabet for the Slavic language in Greece, and not in the Cyrillic alphabet which was the official alphabet of neighboring Bulgaria and Serbia - this also shows the intent of the Greek government to create a distinctively Slavic minority, not a Bulgarian or Serbian minority; the result being that Bulgaria and Serbia would have no right to interfere in Greece's internal affairs.

In October 2006 [4] [5] [6], the Rainbow Party in Greece reprinted the original Abecedar Slavic language primer in Thessaloníki, Greece, which was printed in Athens in 1925 and was based on the Florina/Lerin dialect, as well as an up to date primer in the standardized Macedonian language and script as taught in the Republic of Macedonia and presented it to the Greek Ambassador to the OSCE, Mr Manesis [7] [8]. The book is being distributed to people who identify as Macedonian speakers in northern Greece and it has been successfully promoted in the city of Thessaloníki [9].

At present there is no formal teaching of this language within Greece[46] but it is possible to attain a private tutor. The language is used primarily in the home and within informal situations.[46].

The Metaxas regime

On the 4th August 1936 the authoritarian regime of General Metaxas came to power, and a new state sponsored policy of Hellenisation was enacted. The aim was to Hellenise all the non-Greek speaking Orthodox Christian populations within the Greek state's territory; other Balkan countries (Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania and Albania) respectively followed similar policies. In Greece, the ensuing result left the Slavic speakers (and other minority speech communities) forcibly suppressed, and their privileges under the Treaty of Sèvres withdrawn. Policies of the Metaxas regime included forcible Hellenization of Personal and Surnames, Punishment for speaking a non-Greek language and changing of all Slavic toponyms[46][47].

Present situation

At present, the number of Slavophones in Greece is unknown. In the latest census posing a question on mother tongue (1951), 41,017 people declared themselves speakers of Slavic. Almost all Slavic speakers today in Greek Macedonia also speak Greek[citation needed] and most regard themselves as ethnically and culturally Greek[citation needed]. Many of those for whom a non-Greek identity was particularly important have tended to leave Greece during the past eighty years[citation needed]. Very few speakers can understand written Macedonian and Bulgarian and according to Euromosaic, the dialects spoken in Greece are mutually intelligible[48] as is the case with the Macedonian and Bulgarian languages. Some linguists used the term "Greek-Slavic" instead of the confusing interchangable terms "Macedonian" and "Bulgarian".

Political Representation

A political party that promotes the concept and rights of the "Macedonian minority in Greece", and refers to the Slavic language as Macedonian - the Rainbow Party (Ουράνιο Τόξο) - was founded in September 1998, and received 2,955 votes in the region of Macedonia in the 2004 elections. Rainbow didn't participate in the Greek legislative election, 2007 citing financial reasons[49].Similarly, a pro-Bulgarian political website, known as Bulgarian Human Rights in Macedonia (Βουλγαρικά Ανθρώπινα Δικαιώματα στη Μακεδονία) was founded in June 2000, promoting the concept and rights of what they describe as the "Bulgarian minority in Greece", and prefers to designate the local Slavic language as Bulgarian. Currently this political party operates only a website.

See also

- Greece

- Aegean Macedonians

- Macedonia (Greece)

- Bulgarian language

- Macedonian language

- Bulgarians

- Macedonians (ethnic group)

- Slavic speaking minority of Greece

- Slavic peoples

- Slavic languages

References

- ^ a b Στη Δυτική Μακεδονία, κυρίως στις περιοχές της Φλώρινας, της Καστοριάς, της Βέροιας και του Κιλκίς υπάρχουν άνθρωποι οι οποίοι μιλούν (και) μία διάλεκτο που ονομάζουν «μακεντόνσκι», κι έχει ομοιότητες με τη γλώσσα που μιλούν στην ΠΓΔΜ, η οποία, με τη σειρά της, έχει σαφώς βουλγαρικές καταβολές.

- ^ UCLA Macedonian, UCLA Bulgarian

- ^ Шклифов, Благой. Проблеми на българската диалектна и историческа фонетика с оглед на македонските говори, София 1995, с. 14.

- ^ Шклифов, Благой. Речник на костурския говор, Българска диалектология, София 1977, с. кн. VІІІ, с. 201-205,

- ^ Mladenov, Stefan. Geschichte der bulgarischen Sprache, Berlin, Leipzig, 1929, § 207-209.

- ^ Mazon, Andre. Contes Slaves de la Macédoine Sud-Occidentale: Etude linguistique; textes et traduction; Notes de Folklore, Paris 1923, p. 4.

- ^ Селищев, Афанасий. Избранные труды, Москва 1968, с. 580-582.

- ^ Die Slaven in Griechenland von Max Vasmer. Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften, Berlin 1941. Kap. VI: Allgemeines und sprachliche Stellung der Slaven Griechenlands, p.324.

- ^ Cousinéry, Esprit Marie. Voyage dans la Macédoine: contenant des recherches sur l'histoire, la géographie, les antiquités de ce pay, Paris, 1831, Vol. II, p. 15-17, one of the passages in English - [1], Engin Deniz Tanir, The Mid-Nineteenth century Ottoman Bulgaria from the viewpoints of the French Travelers, A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University, 2005, p. 99, 142,Kaloudova, Yordanka. Documents on the situation of the population in the southwestern Bulgarian lands under Turkish rule, Военно-исторически сборник, 4, 1970, p. 72

- ^ Pulcherius, Receuil des historiens des Croisades. Historiens orientaux. III, p. 331 – a passage in English -http://promacedonia.org/en/ban/nr1.html#4

- ^ Report on the Pomaks, by the Greek Helsinki Monitor

- ^ Who Are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton Indiana UP, 2000 ISBN 0253213592. p. 85, The Interwar period - Greece.

- ^ "Резолюция о македонской нации (принятой Балканском секретариате Коминтерна" - Февраль 1934 г, Москва

- ^ :bg:s:Дописка от село Високо

- ^ Шклифов, Благой and Екатерина Шклифова, Български деалектни текстове от Егейска Македония, София 2003, с. 28-33

- ^ U.S.ENGLISH Foundation Official Language Research - Greece: Language in everyday life

- ^ http://books.google.com.au/books?id=JxCnAHCCuxYC&printsec=frontcover&dq=macedonians+in+greece&sig=67hHATiJ2xY16hXJ0c8Z3zrX5C8

- ^ Trudgill P., 2000, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity". In: Stephen Barbour and Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford : Oxford University Press, p.259.

- ^ Schmieger, R. 1998. "The situation of the Macedonian language in Greece: sociolinguistic analysis", International Journal of the Sociology of Language 131, 125-55.

- ^ a b c Stoyko Stoykov. Bulgarian Dialectology. Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Publishing House, 4th Edition, Sofia, 2002, pp. 170-186

- ^ стр.247 Граматика на македонскиот литературен јазик, Блаже Конески, Култура- Скопје 1967

- ^ bg:s:Дописка от село Бобища

- ^ Topolinjska, Z. (1998). "In place of a foreword: facts about the Republic of Macedonia and the Macedonian language" in International Journal of the Sociology of Language. Issue 131

- ^ стр. 244 Македонски јазик за средното образование- Стојка Бојковска, Димитар Пандев, Лилјана Минова-Ѓуркова, Живко Цветковски- Просветно дело- Скопје 2001

- ^ Friedman, V. (2001) Macedonian (SEELRC)

- ^ Poulton, Hugh. (1995). Who Are the Macedonians?, (London: C. Hurst & Co. Ltd:107-108.).

- ^ Z. Topolińska- B. Vidoeski, Polski~macedonski- gramatyka konfrontatiwna, z.1, PAN, 1984

- ^ Friedman, V. (1998) "The implementation of standard Macedonian: problems and results" in International Journal of the Sociology of Language. Issue 131

- ^ a b Sussex, Roland (2006). The Slavic Languages. Cambridge University Press. pp. p.509. ISBN 0521223156.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Trudgill P., 2000, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity". In: Stephen Barbour and Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford : Oxford University Press

- ^ Trudgill, P. (1992) "Ausbau sociolinguistics and the perception of language status in contemporary Europe" in International Journal of Applied Linguistics. Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 167-177

- ^ Human Rights Watch

- ^ U.S.ENGLISH Foundation Official Language Research - Greece: Language in everyday life

- ^ See Ethnologue ([2]); Euromosaic, Le (slavo)macédonien / bulgare en Grèce, L'arvanite / albanais en Grèce, Le valaque/aromoune-aroumane en Grèce, and Mercator-Education: European Network for Regional or Minority Languages and Education, The Turkish language in education in Greece. cf. also P. Trudgill, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity", in S Barbour, C Carmichael (eds.), Language and nationalism in Europe, Oxford University Press 2000.

- ^ Minority Rights Group,Minorities in the Balkans, page 75.

- ^ Jacques Bacid, Ph.D. Macedonia Through the Ages. Columbia University, 1983.

- ^ GeoNative - Macedonia

- ^ L. M. Danforth, The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World 1995, Princeton University Press

- ^ Hill, P. (1999) "Macedonians in Greece and Albania: A Comparative study of recent developments". Nationalities Papers Volume 27, 1 March 1999, page 44(14)

- ^ [Macedonia and Greece - The Struggle to Define a New Balkan Nation Macedonia and Greece - The Struggle to Define a New Balkan Nation, John Shea]

- ^ Poulton, H.(2000), "Who are the Macedonians?",C. Hurst & Co. Publishers

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/new-multimedia/pdf/wordat077.pdf

- ^ UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile

- ^ UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile

- ^ European Commission

- ^ a b c Greek Helsinki Monitor (Ghm) &

- ^ Denying Ethnic Identity, The Macedonians of Greece

- ^ Euromosaic - Le [slavo]macédonien / bulgare en Grèce

- ^ Press release of Rainbow

Bibliography

- Trudgill P. (2000) "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity" in Language and Nationalism in Europe (Oxford : Oxford University Press)

- Iakovos D. Michailidis (1996) "Minority Rights and Educational Problems in Greek Interwar Macedonia: The Case of the Primer 'Abecedar'". Journal of Modern Greek Studies 14.2 329-343 [10]