Florina

|

Municipality of Florina Δήμος Φλώρινας |

||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Basic data | ||

| State : |

|

|

| Region : | Western Macedonia | |

| Regional District : | Florina | |

| Geographic coordinates : | 40 ° 47 ' N , 21 ° 24' E | |

| Area : | 827.62 km² | |

| Residents : | 32,881 (2011) | |

| Population density : | 39.7 inhabitants / km² | |

| Post Code: | 53100 | |

| Prefix: | (+30) 23850 | |

| Community logo: | ||

| Seat: | Florina | |

| LAU-1 code no .: | 1701 | |

| Districts : | 4 municipal districts | |

| Local self-government : |

1 city district 47 local communities |

|

| Website: | www.cityoflorina.gr | |

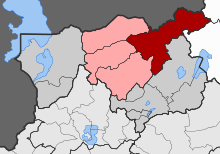

| Location in the West Macedonia region | ||

Florina ( Greek Φλώρινα ( f. Sg. ), Albanian Follorinë / Follorina, Bulgarian / Macedonian Lerin Лерин ) is a municipality and city in the northern Greek administrative region of Western Macedonia. The municipality of Florina includes four municipal districts with a total of 45 localities, including the municipalities of Kato Klines , Meliti and Perasma , which were independent until 2010 .

Geography, climate and geology

geography

The municipality of Florina is located in the northwestern area of mainland Greece, east of the triangle between Albania , North Macedonia and Greece. The city of Florina is about 37 km as the crow flies from the three-country corner. The municipality of Florinas comprises the northern plateau of Eordea (also known as the Bitola-Florina-Kozani basin) or the plain of Lynkestis , which continues north towards Bitola , where the state border with North Macedonia delimits the municipality. In the west the area rises into the mountains of the northern Pindos Mountains , the massifs of the Varnoundas and the Vigla separate Florina from the municipality of Prespes . In the southwest the Verno forms the border with the municipality of Kastoria . A ridge around 30 kilometers long separates Florina from the southwestern community of Amyndeo . In the northeast, a strip a few kilometers wide extends to the Voras massif; here is the border to Central Macedonia with the municipalities of Almopia and Edessa .

North-east of the Vitsi (1927 m) in the Verno massif is the highest settlement in the municipality of Florina, the village of Koryfi, at an altitude of 1350 m, followed by the village of Trivouno (altitude of 1180 m) and Akritas (altitude of 1020 m).

The waters of Florina collect in the Sakoulevas or Lyngos, which flows through the city of Florina coming from the west and drains to the north via the Crna Reka and the Vardar into the Aegean Sea. Tributaries of the Sakoulevas are the Paliorema, which flows into it from the Voras massif from the northeast, and the Palio, which flows into the Sakoulevas from the northwestern municipal area. The highest point in the municipality of Florina is the summit Voras (2525 m) in the northeast; at the exit of the Sakouleva from the municipality is located at 580 m above sea level. d. M. the deepest point of the municipality.

The central part of the municipality is characterized by the agricultural use of the Florina plateau. According to the cultivation of grain, cotton and other agricultural products, this part of the municipality is designed accordingly by humans and has few original landscape features. In the west of the municipal area, the urban landscape of the city of Florina dominates with dense buildings. In addition to buildings with origins in the second half of the 20th century, the city of Florina still has a relatively large number of buildings from the 19th century, which can be seen as a reflection of the typical architecture of the time. Immediately west of the city of Florina, the landscape changes considerably with the mountain ranges of Varnoundas and Verno and the Sakoulevas river between the mountain ranges. This part of the municipality consists of deciduous and mixed forests on the mountain slopes. The agricultural use is limited to the narrow valley of the Sakouleva. The municipality of Florina has no inland waterways worth mentioning, such as artificial and / or natural lakes.

climate

The city and municipality of Florina, due to their location on mainland Greece, are subject to the conditions of dry continental climates. Summers are warm to hot and relatively short; the winters are cold and relatively long.

The average daily temperatures in Florina were 19.7 ° C in June, 22.0 ° C in July and 21.9 ° C in August. According to the Greek Meteorological Service, the average daily temperatures were 21.0 ° C in June, 23.1 ° C in July and 22.5 ° C in August. The average maximum temperatures per day were 26.2 ° C in June, 28.8 ° C in July and 14.2 ° C in August. The average minimum temperatures per day were 12.5 ° C in June, 14.4 ° C in July and 14.2 ° C in August. In June there was an average of 7.4 days of rain, in July on 6.1 days and in August on 5.8 days with an average rainfall of 37.3, 34 and 31 mm. The mean humidity was 59.8%, 57.4% and 58.3%.

The daily average temperatures in winter are 7.9 ° C in November, 3.8 ° C in December, 0.4 ° C in January, 2.8 ° C in February and 6.2 ° C in March. The heating season is corresponding: according to a study between 1983 and 1987, Florina was heated 217 days per year. The heating season started in September and ended in May. The total amount of precipitation over a year is 813 mm. In 10 out of 12 months of a year the amount of precipitation exceeds 50 mm; in the months of October and November 100 mm. Precipitation in winter is also snowfall in Florina, which can reach a considerable extent. Snowfalls can also occur in Florina in March and April.

The maximum temperature measured in Florina was 40.8 ° C, the minimum -21.4 ° C.

|

Average monthly temperatures and rainfall

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

geology

The municipality of Florina is located in the Pelagonian Zone, which runs through mainland Greece from north-northwest to south-southeast. In the region of the municipality of Florina, this zone has different geological components. The city of Florina itself as well as all municipal areas and districts that are to the east of the Verno massif in the plain are based on deposits from the Tertiary and Quaternary eras . The municipal areas, which lie on the slopes and heights of the Verno massif, are based on slate and gneiss from the Palaiozoic. The gneiss rocks from Florina were determined to be between 692 and 706 and 698 to 731 million years old (geological age of the Neoproterozoic ). They represent the remains of a terran - the Florina Terran - which was an active continental edge on the northern edge of the continent Gondwana in the past .

Like all of Greece, the municipality of Florina is prone to earthquakes . The strongest earthquake observed in the region so far reached a magnitude (M) of 6.6 on the Richter scale . According to the four-stage earthquake risk classification (based on the probability of severe earthquakes, where I means low and IV very high probability) Florina belongs to Zone II according to the classification according to the earthquake protection laws of Greece from 2003 (for comparison: Athens III, Thessaloniki III, Zakynthos IV , Corinth IV, Syros I, Naxos I).

history

Finds and excavations have shown that the area of Florina has been around since at least 6000 BC. Is inhabited.

Antiquity

In ancient Greece, today's area around Florina was called Lynkestis (Lynkistis). The name Lynkestis comes from the Greek word Lynkos or Lykos , which translated means wolf . Lynkestis described the south-western part of Macedonia and bordered on Illyria. The inhabitants, the Lyncestai (Lyncestes) are said to have been Illyrians. In 1997, in excavations in the immediate vicinity of the church of Agios Pantelimonas near Florina, remains of the acropolis of the ancient settlement Iraklia Lyngistis (Heraklia Lynkestis or Heraclea Lyncestis) were made. The settlement of Heraklea Lynkestis was on the border of the Lynkestis region with Illyria. 391 BC BC King Argeos of Lynkistis took over power over all of Macedonia for a short time . The Macedonian King Philip II recaptured the Lynkestis and added them to the Macedonian kingdom. Various important personalities of the Macedonian kingdom came from Lynkestis: Leonatos, Pelagos, Aeropos, Krateros and Eurydice, the mother of Philip II and grandmother of Alexander the great . The de facto sovereignty over today's Florina was taken over by the Romans after the Macedonian defeat at the Battle of Pydna in 168 BC. 148 BC BC Heraklia Lynkestis (today's Florina) becomes a Roman province like the rest of Northern Greece. Heraklia Lynkestis was an important stopover on the Roman Via Egnatia from Byzantium via Thessaloniki to Dyrrachium .

Byzantine era

The division of the Roman Empire in 395 AD brought the area of today's Florina under the control of the Eastern Roman Empire , the later Byzantine Empire . Under the rule of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I , Florina is known as "Iraklia Lakkou". Between the 6th and 7th centuries AD, Slavic people settled in the area of the Florina municipality as part of the Slavic conquest of the Balkans . In the 9th century, the area of today's Florina municipality was conquered and temporarily controlled by the Bulgarians. In the 10th century, the Byzantine Empire succeeded in recapturing the areas of Macedonia, including the area of today's municipality of Florina. The Byzantine Emperor Basil II and the Bulgarian Tsar Samuel fight an armed confrontation in the area of Skopos in 1017. With the conquest of Constantinople in 1204 as part of the fourth crusade and the subsequent establishment of Latin empires and kingdoms on the territory of the Byzantine Empire, Byzantine rule ends for the time being. Florina falls to the Kingdom of Thessaloniki ; Florina cannot keep this up for long. In the armed conflicts against the Greek Byzantine successor state Despotate Epirus , Florina is lost to the latter and thus again under "Greek sovereignty". With the defeat of the Despotate Epirus in 1259 against the newly strengthened Byzantine Empire, Florina also falls under direct control of the Byzantine Empire. This persists until the end of the 14th century. During this time, the Byzantine historian and Emperor John VI. Kantakuzenos the area as Flerinon . The Byzantine rule is interrupted by Serbia under King Stefan Uroš IV Dušan . This conquered large parts of the Greek mainland in the middle of the 14th century, including Florina. After the death of the Serbian king, however, Serbian rule could not hold and Florina again fell to the Byzantine Empire.

Ottoman rule

At the end of the 14th century, the Ottomans under Sultan Murad I conquered Florina and referred to the area as Fiurina . The name Florina also remained in use. In the 15th century people of the Jewish faith settled in Florina. From 1630 to 1634, Florina and its surrounding region were an independent vilayet based on Ottoman head tax lists. The Liva of Pasha was superordinate to the vilayet as an administrative structure. In the further course the administrative structure changed: Manastir (Monastir, today's Bitola ) became the seat of a vilayet of the same name and also included the area of today's municipality of Florina, which lost the status of a vilayet and became a subordinate administrative unit, the Kaza (Kaza Florina) . Ottoman rule was not interrupted until the conquest of Florina by Greek troops on November 20, 1912. The Greek war of liberation from 1821 to 1829 also affected the region of Macedonia and thus also Florina, especially from 1821 to the first months of 1822. However, the insurgents did not succeed; the Ottoman occupation forces put down the rebels. In 1836 Florina belongs to the Paschalik ( Vilâyet ) Manastir (Bitola). In 1837 Nizam Pasha becomes administrator of the Manastir vilayets, which also includes the regions around Kailar ( Ptolemaida ), Prilip ( Prilep ), Ochrid, Prespa, Siatista , Grevena and Koritsa ( Korce ). The nationalist tendencies that became violently visible with the Greek War of Independence subsequently determine the course of the history of the city and the Florina region as well as the Macedonia region as a whole.

Modern times

The 19th and early 20th centuries

The 19th and the beginning of the 20th century in Florina was dominated by the so-called “Macedonian question” and the contradictions of the ethnic groups in the region of Macedonia, namely Greeks, Ottomans, Albanians , Wallachians ( Aromanians ), Bulgarians and Macedonians . The Ottoman Empire and with it the region around Florina was economically and militarily lagging behind the Western European countries and even compared to the Russian Empire . Lost wars, especially against Russia, but also Serbia and Bulgaria, marked the state of the Ottoman Empire as well as the growing influence of Western states such as France, Germany and Great Britain. One point of contention among the individual population groups in Macedonia was, for example, the Millet system (limited self-administration according to aspects of religious affiliation). This system led, for example, to the administration of the Orthodox Bulgarian population by the Greek Orthodox Church and, in the middle of the 18th century, to the Bulgarian-Greek church struggle . It was not until 1870 that the Ferman for the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate, under Russian pressure, changed the Millet system so that the Bulgarian population group was administratively subordinate to the Orthodox Bulgarian Exarchate and was thus removed from the control of the Greek Orthodox Church.

The interethnic tensions also erupted in repeated armed uprisings against the Ottoman occupation forces. In February 1854, an uprising against the Ottoman occupation broke out in the entire region of Macedonia, mainly of the Greek population group. The main focus of the fighting is in Epirus, but areas in Macedonia such as Chalkidiki or Thessaloniki and Thessaly are also places of revolt. Despite the parallel Russian-Ottoman war ( Crimean War ), Ottoman forces succeed in suppressing the uprising in June 1854. In January 1878 the Greek population group rises under the leadership of the "Nea Filiki Eteria" ("Νέα Φιλική Εταιρεία"), which was founded in 1865 in the city of Florina. , a naming with allusion to Filiki Eteria of the Greek Revolution) against the Ottoman occupation (see also Balkan crisis ). The uprising was evidently encouraged by the Russo-Ottoman War of 1877-1878. In the Treaty of Berlin in 1878 Bulgaria is independent. The population groups in Rumelia, including the region of Macedonia and Florina, are granted religious autonomy. A solution to the Macedonian question will not be achieved by these regulations. The uprising continues accordingly. In November 1878 there were four main arenas: Mount Olympus, where mainly Greek insurgents fight, and three other areas, where mainly Bulgarian insurgents fight. Due to the end of the Russo-Ottoman War, the Ottoman Empire can move additional forces (23 battalions) to the contested areas. At the end of 1878, or at the latest in 1879, the entire region of Macedonia was quiet - the uprisings were ended by the Ottoman forces. In 1880 the Kingdom of Greece received Thessaly and part of Epirus from the Ottoman Empire. The region of Macedonia is not affected by these territorial concessions. In addition to these ethnic tensions, the situation was also worsened by a bad harvest in the Macedonia region; Grain had to be imported from America.

1903 performs Ilinden uprising (also Ilinden Probraschenie uprising called) under the guidance of BMARK ( Bulgarian Macedonian-Adrian Opeler Revolutionary Committee / Български Македоно-Одрински революционни комитети, a forerunner of the later IMRO ) to violent confrontation between the / the Slavic population (n ) and the Ottoman occupation forces. Depending on the point of view or historical view, this uprising is viewed as a joint, solely Bulgarian or solely Slavic-Macedonian uprising against the Ottoman occupying power. The main focus of the disputes was on the one hand the Vilayet Manastir around the village of Krushevo (see Republic of Krushevo), on the other hand the Vilayet Edirne in the Strandschagebirge (see Malko Tarnowo ) at today's border triangle Bulgaria-Turkey-Greece. In the region of Florina, fierce fighting raged against the Ottoman occupation forces; the city of Florina was obviously less affected by the fighting than the surrounding towns. The uprising was viewed by external press monitoring (for example the New York Times) as a "Bulgarian uprising". On August 20, 1903, official Ottoman reports designate the strongholds of the Ilinden uprising with Krushevo, Merichoro and Florina. On August 21, the village of Armensko, today's Armenochori and part of the Florina municipality, was heavily shelled by Ottoman troops. On the same day 12 Ottoman battalions were marched from Manastir (Bitola) in the direction of Florina. At the end of August 1903 the fighting reached its apparent maximum. The village of Armensko (Armenochori) was completely surrounded by Ottoman and Albanian troops. The local population and the trapped insurgents were killed by the Ottoman and Albanian troops, according to eyewitness reports. In the city of Florina itself, the same eyewitness describes a climate of fear. The Greek population was instructed by the local bishop (metropolitan) of the Greek Orthodox Church not to leave Florina despite the fierce fighting in the area. The fact that the Greek population group remained in Florina obviously led to massive attacks, including assassinations, by the Ottoman and Albanian armed forces deployed. As a result of the fighting, 15,000 people from the Bulgarian population are said to have fled to the Vitsi mountains. On September 14, 1903, the correspondent for The Times newspaper reported that the village of Armensko (today: Armenochori) was predominantly populated by Greeks. It was said to have been trapped by the Ottoman troops, which were moving west through the valley of the Sakouleva towards Pisoderi, and subsequently burned down. An evacuation of the population of Armensko (today: Alona) did not take place.

This escalation of violence was not without backlash. Although the Ilinden uprising was suppressed by the Ottoman troops by the end of 1903, acts of violence between the individual population groups escalated in the following years. On October 21, 1904, Greek Andarten kill 20 Bulgarian insurgents near the city of Florina. On November 14, 1905, Greek gangs shot and killed 6 members of the Bulgarian population near Florina during a wedding and then burned the building down, killing 15 people.

Despite these violent and also "bloodthirsty" national and nationalist opposites, which showed both ethnic and economic motivation, the Young Turkish Revolution in 1908 , for example, led to fraternization scenes, albeit of very short duration. The Young Turkish Revolution was well received by the residents of Florina. The Turkish writer Necati Cumalt, born in Florina, describes pronounced manifestations of joy in the last week of July 1908. As early as August 1908, the same author describes a return to “insecurities and fears of earlier anger, deep-rooted struggles [and] hatred [...] . “The Muslim population group felt the amnesty of associations and organizations with attacks against the Muslim population group as not good.

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, Florina was described as a city with 11,000 mostly Muslim inhabitants as well as 3 mosques and a Greek church. At that time, Florina was the seat of the Greek Orthodox Bishop of Moglena and the seat of a Kaimakam (governor). This was in front of the Sanjak (Kaza) of Florina.

Balkan Wars

In October 1912, the First Balkan War broke out between Montenegro, Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece on the one hand and the Ottoman Empire on the other. After the Battle of Giannitsa, which was successful for Greece on November 1 and 2, 1912, the 5th Greek Division under Colonel Mathiopoulos split off from the main force striving for Thessaloniki and marched towards Florina. On November 5 and 6, 1912, the first battle of Vevi, also known as such, took place at the Klidi Pass. The Ottoman forces were able to repel the Greek attack for the time being. After the fall of Thessaloniki, Greek troops were deployed in the direction of Bitola to the northwest from Thessaloniki. The simultaneous Serbian victory in the Battle of Bitola and the capture of the city on November 19, 1912 led to increasing military pressure and weakened the defensive position east-southeast of Florina at the Klidi Pass, so that the Greek 5th Division after regrouping the Klidi Pass crossed and took the city of Florina on November 20, 1912. The Greek armed forces then advanced further west and northwest and crossed the Albanian border.

A short time later, at the end of June 1913, the states allied in the First Balkan War faced each other as opponents in the Second Balkan War : an alliance of Greece and Serbia (later Romania) was directed against Bulgaria. In the peace negotiations with the final Bucharest Treaty of August 16, 1913, Serbia and Greece did not agree on a border line between the two states. A border finding commission set up according to the contract then determined the Greek-Serbian border. The representative of the Serbian Foreign Ministry Čaponić in Bitola intended to claim the area around the city of Florina for Serbia. At the beginning of October 1913, the work of the Boundary Determination Commission was ended; Florina and the surrounding region was added to Greece, the defined border corresponds to today's northern Greek border in the area of the prefecture of Florina.

In May 1913, an archeology office was established in Florina.

First World War

During the First World War , the area around Florina was one of the main combat areas between the Allies and the Central Powers on Greek territory (along with East Macedonia and West Thrace). After Austria-Hungary's unsuccessful offensives on Serbia in 1914, Serbia, which at that time was directly adjacent to Greece and thus also to the region around Florina, was defeated by the armed forces of the Central Powers in autumn 1915 (including Bulgaria after its entry into the war on the side of the Central Powers) conquered. The Serbian army was driven from Serbia towards Montenegro on the Adriatic coast and then taken to the island of Corfu by French ships. Despite Bulgaria's entry into the war, which after the lost Second Balkan War in 1913 still had territorial claims with regard to Central and Eastern Macedonia and Western Thrace, the Greek northern border was respected until 1916 as a result of Greek neutrality at the beginning of the First World War. With the landing of French and British troops in Thessaloniki in 1915, Greek neutrality officially existed until 1917, but de facto the Greek counter-government under Eleftherios Venizelos joined the Allied powers of the Entente in 1916.

Emil Ludwig , who visited the city in 1915, describes the Florina at that time:

“Florina - the first destination - is dangerous or takes on the appearance. A sticky mass of men billows around in the dark streets, many of them dressed in Turkish, mostly with daggers, if not armored with Brownings, which you can guess where they have remained invisible. The place is full of Ententist agents, spies, smugglers, and every German has been advised long before his rolling car lures people onto the main street.

But the twenty-six-year-old prefect - since then deposed by the French because of friendship with Germans - and a Greek doctor, a refugee from Monastir, speak German like everyone who studied with us, and the prefect above all wastes such an abundance of politeness on foreigners that one in his sphere forgets the darkness of his citizens who crouch around corners, under bridges, in front of pubs, like the Bravo in the old opera. "

On June 19, 1916, Bulgarian troops began their advance on the Salonika Front on Greek territory north of Florina. After little fighting at first, the Bulgarian armed forces succeeded in taking the city of Florina on August 18, 1916. The Greek troops in the affected areas did not take part in the fighting and remained neutral. The population of Florina fled from the advancing Bulgarian troops in the direction of Amyndeo (Sorovits). The city of Florina and today's area of the municipality of the same name was occupied by the troops of Bulgaria and the Central Powers. On September 8, 1916, the German city commander Florinas asked the Greek administration to leave Florina after the Greek politician Eleftherios Venizelos had declared a counter-government to the royal government in Athens and actively promoted the entry of Greece into the First World War on the side of the Allies . On September 13, 1916, Serbian and French troops retook Amyndeo (Sorovits) from the Bulgarians, starting the offensive to retake Florina. On September 16, 1916, the Allied troops reached the Broda River 10 km northeast of Florina, pushing back the Bulgarian troops. The city of Florina, including the strategically important train station, was taken by combined French-Russian troops on September 18, 1916. Only one day later, the Allied troops crossed the northern Greek border north of Florina.

Between the world wars

The period between the end of the First and the beginning of World War II (1918–1940) did not bring any political calm to the city of Florina. After the Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish War from 1919 to 1922 (the so-called "Asia Minor Catastrophe"), the population exchange of 1.5 million Greeks and 0.5 million Turks agreed in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne led to a change in the composition of the population in Florina . The Turkish population decreased, the Greek increased. The Turkish writer Necati Cumalı had to leave his hometown Florina as part of this population exchange. In the year of the population exchange in 1923, the existence of a Mufti post in Florina also ended.

In the years 1921 to 1925, the mortality rate in the population group of refugees from malaria was 15–75%, according to the Society for an Anti-Malaria Campaign. The refugee settlement committees and international aid ( League of Nations ) tried to control or push back malaria among the refugees as well as among the local population by means of massive use of quinine .

From 1912 onwards, by decree of the Greek government, place names of Slavic and / or Turkish origin were renamed into Greek place names (see renaming of Ptolemaida and Giannitsa). The city of Florina itself was not affected by this renaming, as the name Florina was also in use in Ottoman times, regardless of the Slavic name Lerin used at the same time. The renaming was given a legal basis with the royal decree of May 6, 1909: with this law a "Commission for Place Names" (Epitropi Toponymion) was founded. The current municipality of Armenochori received the name in use today 1919 (until then: Ermenovo or Armenovo or Armenoro), Mesonisi 1926 (until then: Lazeni), Simos Ioannidis 1957 (until then: Mostesnica), Trivouno 1927 (until then: Tyrsia), Alona 1927 (until then: Armensko), Koryfi 1927 (until then: Touria), Proti 1928 (until then: Kambasnica) and Skopia 1927 (until then: Skritsova).

With the beginning of the quasi-fascist dictatorship under Ioannis Metaxas in 1936, the political pressure on the Slavic population increased. Assuming relations with “opponents of Greece”, users of the Slavic language or languages faced prison sentences.

Second World War

The Second World War began for Florina with the Italian attack from Italian-occupied Albania on Greece on October 28, 1940. One of the thrusts of the original Italian plan of attack was aimed at Florina and envisaged its conquest by Italian troops (see map). Two Italian divisions were supposed to capture Florina with a pincer movement. The Italian troops managed to advance on Greek territory, especially in the Pindos Mountains as far as Vovousa and Konitsa ; Florina and especially the city of Florina were not reached by Italian troops. According to German sources, the Italian attack got stuck after a few days "without even remotely reaching its goal". Within a week, in November 1940, Greek troops from Florina opened an offensive against the Italian troops and pushed them back into Albanian territory towards Korça (Koritsa).

On April 6, 1941, German troops of the 12th Army under the command of General Field Marshal Wilhelm List attacked the Greek defensive positions along the Metaxas Line east of the Axios River valley on a broad front ( Operation Marita ) from their deployment positions on Bulgarian territory . On April 9, 1941, after conquering the city of Bitola (Monastir, Manastir) in what was then South Serbia (now North Macedonia) - including the 1st SS Panzer Division and the XXXX. motorized army corps to the south and reached the Greek territory north of Florina. Greek forces to defend the city and the plain of Florina had to be relocated in a hurry, as most of the Greek troops were either east of the Metaxas Line or facing Italian troops to the west on Albanian territory. Two Greek divisions faced the German attackers, who penetrated through the so-called "Monastir gap" via Bitola to the south on Greek territory. On April 10, 1940, the city of Florina was captured by German troops, despite strong resistance from Greek troops. The fighting between German and Greek troops continued for the next two days; East-southeast of Florina, German troops met armed forces of the British, Australian and New Zealand expeditionary corps near the village of Vevi and broke through their defensive positions on April 12, 1941. After the final Greek defeat at the end of April 1941, Florina and the area around Florina remained in the German occupation zone, which stretched from Florina to the Strymonas River in northern Greece . Italy, which had occupied Albania and from there attacked Greece on October 28, 1940, raised territorial claims to Florina, which should be added to Albania. This was countered by Bulgarian claims, which were based on the ethnic affiliation of the population of Florina to Bulgaria (“purely Bulgarian population”).

The approximately 400 Jewish community in the city of Florina was deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp on May 9, 1943, together with the Jewish communities from Veria, Thessaloniki, Soufli, Didymoticho and Orestiada and murdered there.

In 1943, after Italy converted to the Allies, 200 Italian officers from Corfu and Kefallinia were interned in Florina. Another 800 Italian soldiers from the Modena division were forced to do labor in the Florina region after 1943.

Activities of resistance against the German occupation forces began in 1943. The war diary of the Wehrmacht High Command mentions gang activities in the Florina area several times.

In addition to resistance, there were also collaborations with the German occupiers. Individual members of the Bulgarian population group identified with the German ally Bulgaria and joined the army. Already after the Italian attack Italian propaganda efforts had the project, Slavic population under the provision of greater independence on the Italian side to the armed conflict to move. Individual members of the Slavic population groups followed these calls, which were thwarted by the Italian efforts to incorporate Florina into Albania.

At the end of October 1944, the German troops withdrew from Florina.

Greek Civil War

During the Greek civil war from mid-1946 to mid-1949, the municipality of Florina was the scene of repeated armed conflicts between the left-wing rebels of the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE) under communist leadership and the regular Greek army under the command of the more right-wing government in Athens. One of the two strongholds of the rebels under communist leadership was located southeast of the city of Florina in the area of today's municipality of Florina: Mount Vitsi with its northern and northeastern flanks.

Before the actual acts of war broke out, the government in Athens held a referendum on the question of the monarchy or republic in Greece. 25,961 voters were listed in the Florina prefecture on the electoral roll, 17,477 voters cast their votes. 8,056 voters voted for the republic and the permanent abolition of the monarchy, and 9,250 voters for the monarchy with 170 invalid votes. The residents of the Florina prefecture voted in line with the majority throughout Greece. In the subsequent fighting, Florina remained calm at first. In January 1947 the fighting draws closer to Florina; a telephone line is sabotaged and two villages in the area of the Prespa Lakes are looted. On February 1, 1947, Argyrios Dimou from the village of Trivouno in the municipality of Florina, located on the northern flank of Mount Vitsi, was executed after being sentenced to death for illegally possessing weapons; his brother Georgios Dimou received a life sentence for collaborating with the insurgents. At the end of May, the city of Florina was immediately shelled by insurgents. Obviously, the city's arterial roads were deliberately set on fire. On August 20, 1947, a correspondent for the newspaper Eleftheria described the city of Florina as an army camp ; the urban population feared that they would be the target of insurgent attacks on a daily basis.

In October 1948, the fighting finally reached the municipality of Florina. On October 26, 1948, the rebels captured large parts of the Verno massif, including several villages, from the Greek army. This can still hold the Vitsi summit, which is located in the area of the municipality of Florina, but is under heavy military pressure from the 800 to 1,000 insurgents who lead this attack on the Verno massif. The Verno with its summit Vitsi becomes the second most important base of the insurgents. The desire of the insurgents under the leadership of the Stalinist Zachariadis for a capital for the insurgent movement puts the city of Florina at the center of the fighting. On February 12, 1949 at 3 a.m., mass groups of insurgents with a strength of 4,000 fighters attacked the city of Florina directly and attempted to conquer it, both in house-to-house fighting and by artillery fire from the neighboring mountains. Vitsi, located to the southwest of the city, with its rebellious infrastructure is proving to be an ideal base for such a more conventional military operation. In addition to the Vitsi, the rebels also attacked the Varnous massif to the north. The insurgents initially managed to advance up to 1,000 m from the city limits; then their advance is stuck in the defensive fire. In the heavy fighting in wintery weather conditions with a lot of snow, the Greek army remained victorious and inflicted heavy losses on the insurgents; 618-783-799 dead, approx. 1,500 wounded and 325–350 captured insurgents (depending on the source), including 28 officers, are the result of the battle for Florina, which ends on February 15, 1949. The operation to capture Florina turned into a real fiasco for the insurgents. Despite the attacks on the supply routes of the Greek army south of Vevi (Klidi Pass) and east of Kelli (Kili Derven Pass), the insurgents did not succeed in gaining the upper hand. The Greek army lost 44 dead and 220 wounded in battle. 35 soldiers were missing after the fighting. The DSE's attack on the city of Florina was their last attack on a larger settlement and at the same time their last major attack outside of their focus areas Grammos and Vitsi in the Greek Civil War.

In the further course the insurgents were pushed back further and further to their base at the Vitsi summit. An attack by the insurgents from their base on Vitsi on the village of Derven, southeast of Trivouno, was successfully repulsed by the Greek army on May 15, 1949. At the beginning of August, a major offensive by the Greek armed forces against the Vitsi summit, the Pisoderi pass and the mountains around the Prespa lakes begins. The entire area is conquered within a week; a third of the rebels flee to neighboring Albania, the rebels lose their second most important base after the Grammos massif.

In June 1949 at least 19 villages in the mountains in the Florina region had been evacuated or abandoned by their population: some of the evacuees or refugees fled to the city of Florina.

The acts of war for the city of Florina and the municipality of Florina were completed in mid-August 1949. However, the consequences of the civil war remain clearly visible. On August 22, 1949, one week after the defeat of the insurgents in the Florina area, the military court in the city of Florina sentenced 53 of a total of 112 defendants to death for sabotage and espionage for the Greek guerrillas. 11 more people are sentenced to life imprisonment, another 9 people are imprisoned for 20 years, and 2 more for three years.

post war period

Both the city of Florina and the region suffered from the consequences of the civil war. In 1954 the Greek government under Prime Minister Alexandros Papagos dismissed all “Macedonians” from the public service. In 1959, residents of the villages around Florina and Kastoria were asked to publicly declare that they did not speak Macedonian. It is not known whether the city of Florina was explicitly affected. In spite of these repressive measures, there was also considerable relief for the population: In the same year, the Greek and Yugoslav governments agreed on a regulation for free local border traffic between Greece and Yugoslavia. Residents were allowed to cross freely in a 10 km wide zone north and south of the border. This border traffic sometimes took place without the use of passports. The Greek military junta ended this agreement in 1967. After the end of the military dictatorship and the redemocratization of Greece, the repressive ones against the Slavic-Macedonian population were withdrawn.

The repression measures against the Slavic-Macedonian population on the one hand and the economic situation on the other led to a strong emigration from Florina to European countries (including Germany) as well as to Canada and Australia. Geck identifies the region around Florina (prefecture) as the region most severely affected by labor migration in the period 1961 to 1970.

With the state independence of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia as the Republic of Macedonia, a fierce dispute arose between the new state of Macedonia and Greece over the name of the state. The Ouranio Toxo (or Vinozito) party, which sees itself as the political representative of the (Slavic) Macedonian minority in Greece, was particularly affected by this dispute. In 1995, the party office in the city of Florina was stormed and set on fire by an angry crowd.

Administration, population and politics

Administrative division

The city of Florina had been a municipality (dimos) since 1918 . After 1997 and the then implemented Greek municipal reform Ioannis Kapodistrias , the municipality of Florina was enlarged by a few neighboring towns; With the administrative reform of 2010 , the municipalities Kato Klines , Meliti and Perasma were incorporated on January 1, 2011 . The municipalities from 1997 have since formed four municipal districts (Ez. Gr. Dimotiki enotita ), the municipalities from the period before 1997 are run as municipal districts (gr. Dimotiki kinotita ) or local communities (topiki kinotita) . This results in the following municipality structure (population figures according to the 2011 census):

- Florina municipality - Δημοτική Ενότητα Φλώρινας - 19,985 inhabitants

- Florina Municipality - Δ. Κ. Φλώρινας - 17,686 inhabitants

- Florina - Φλώρινα - 17,686 inhabitants

- Local community Simos Ioannidis - Τ. Κ. Σίμος Ιωαννίδης - 221 inhabitants

- Simos Ioannidis - Σίμος Ιωαννίδης - 221 inhabitants

- Trivouno - Τρίβουνο - uninhabited

- Kalogeritsa - Καλογερίτσα - uninhabited

- Local community Alona - Τ. Κ. Αλώνων - 211 inhabitants

- Local community Armenochori - Τ. Κ. Αρμενοχωρίου - 986 inhabitants

- Local community Koryfi - Τ. Κ. Κορυφής - uninhabited

- Local community Mesonisi - Τ. Κ. Μεσονησίου - 198 inhabitants

- Local community Proti - Τ. Κ. Πρώτης - 120 inhabitants

- Local community Skopia - Τ. Κ. Σκοπιάς - 563 inhabitants

- Florina Municipality - Δ. Κ. Φλώρινας - 17,686 inhabitants

- Municipality of Kato Klines - Δημοτική Ενότητα Κάτω Κλεινών - 2,735 inhabitants

- Local community Agia Paraskevi - Τ. Κ. Αγίας Παρασκευής (Αγία Παρασκευή) - 136 inhabitants

- Local community Akritas - Τ. Κ. Ακρίτα (Ακρίτας) - 100 inhabitants

- Local community Ano Kalliniki - Τ. Κ. Άνω Καλλινίκης (Άνω Καλλινίκη) - 275 inhabitants

- Local community Ano Klines - Τ. Κ. Άνω Κλεινών (Άνω Κλεινές) - 179 inhabitants

- Local community Ethniko - Τ. Κ. Εθνικού (Εθνικό) - 58 inhabitants

- Local community Kato Kallinikis - Τ. Κ. Κάτω Καλλινίκης (Κάτω Καλλινίκη) - 85 inhabitants

- Local community Kato Klines - Τ. Κ. Κάτω Κλεινών (Κάτω Κλεινές) - 394 inhabitants

- Local community Kladorrachi - Τ. Κ. Κλαδορράχης - 97 inhabitants

- Kladorrachi - Κλαδορράχη - 92 inhabitants

- Kimisis tis Theotokou - Κοίμησις της Θεοτόκου - 4 residents

- Local community Kratero - Τ. Κ. Κρατερού (Κρατερό) - 84 inhabitants

- Local community Marina - Τ. Κ. Μαρίνης (Μαρίνα) - 120 inhabitants

- Local community Mesochori - Τ. Κ. Μεσοχωρίου (Μεσοχώρι) - 358 inhabitants

- Local community Mesokambos - Τ. Κ. Μεσοκάμπου (Μεσόκαμπος) - 67 inhabitants

- Local community Neos Kafkasos - Τ. Κ. Νέου Καυκάσου (Νέος Καύκασος) - 229 inhabitants

- Local community Niki - Τ. Κ. Νίκης (Νίκη) - 273 inhabitants

- Local community Parorio - Τ. Κ. Παρορείου (Παρόρειο) - 23 inhabitants

- Local community Polyplatano - Τ. Κ. Πολυπλατάνου (Πολυπλάταν) - 257 inhabitants

- Meliti municipality - Δημοτική Ενότητα Μελίτης - 5,927 inhabitants

- Local community Achlada - Τ. Κ. Αχλάδας - 486 inhabitants

- Achlada - Αχλάδα - 271 inhabitants

- Ano Achlada - Άνω Αχλάδα - 102 inhabitants

- Giourouki - Γιουρούκι - 31 inhabitants

- Local community Itea - Τ. Κ. Ιτέας - 542 inhabitants

- Local community Lofi - Τ. Κ. Λόφων (Λόφοι) - 355 inhabitants

- Local community Meliti - Τ. Κ. Μελίτης (Μελίτη) - 1,432 inhabitants

- Local community Neochoraki - Τ. Κ. Νεοχωρακίου - 518 inhabitants

- Agios Athanasios - Άγιος Αθανάσιος - 33 inhabitants

- Neochoraki - Νεοχωράκι - 485 inhabitants

- Local community Palestra - Τ. Κ. Παλαίστρας - 289 inhabitants

- Local community Pappagiannis - Τ. Κ. Παππαγιάννη - 581 inhabitants

- Local community Sitaria - Τ. Κ. Σιταριάς - 718 inhabitants

- Local community Skopos - Τ. Κ. Σκοπού - 114 inhabitants

- Local community Tripotamos - Τ. Κ. Τριποτάμου - 311 inhabitants

- Local community Vevi - Τ. Κ. Βεύης (Βεύη) - 688 inhabitants

- Local community Achlada - Τ. Κ. Αχλάδας - 486 inhabitants

- Perasma municipality - Δημοτική Ενότητα Περάσματος - 4,234 inhabitants

- Local community Agios Vartholomeos - Τ. Κ. Αγίου Βαρθολομαίου - 213 inhabitants

- Agios Vartholomeos - Άγιος Βαρθολομαίος - 172 inhabitants

- Stathmos Vevis ('Vevi Station') - Σταθμός Βεύης - 41 inhabitants

- Local community Ammochori - Τ. Κ. Αμμοχωρίου - 1,250 inhabitants

- Local community Ano Ydroussa - Τ. Κ. Άνω Υδρούσσης - 229 inhabitants

- Local community Atrapos - Τ. Κ. Ατραπού - 150 inhabitants

- Local community Drosopigi - Τ. Κ. Δροσοπηγής - 239 inhabitants

- Local community Flambouro - Τ. Κ. Φλαμπούρου - 420 inhabitants

- Local community Kolchiki - Τ. Κ. Κολχικής - 231 inhabitants

- Local community Leptokaryes - Τ. Κ. Λεπτοκαρυών - 62 inhabitants

- Local community Perasma - Τ. Κ. Περάσματος - 435 inhabitants

- Local community Polypotamo - Τ. Κ. Πολυποτάμου - 314 inhabitants

- Local community Triandafyllia - Τ. Κ. Τριανταφυλλέας - 64 inhabitants

- Local community Tropeouchos - Τ. Κ. Τροπαιούχου - 323 inhabitants

- Local community Ydroussa - Τ. Κ. Υδρούσσης - 304 inhabitants

- Local community Agios Vartholomeos - Τ. Κ. Αγίου Βαρθολομαίου - 213 inhabitants

population

In the Ottoman period, different population groups lived in Florina: Greeks, Bulgarians, Macedonians, Turks and Albanians. Ami Boué reports for the period between 1830 and 1840 that the Bulgarians also settled the Florina plain, among other things. Among the Slavic population group, Boué distinguishes in her report Serbs, Croats, Bulgarians and Dobrucha Cossacks. The Slavic Macedonians are not designated separately. Boué does not provide exact figures on the Slavic or Slavic-Macedonian or Bulgarian population of the city of Florina. Heinrich Barth reported in his travel description published in 1864 that the city of Florina had around 2,000 inhabitants and was of not insignificant importance. In 1880 Heinrich Kiepert demanded a border drawing between Greece and the Ottoman Empire as a result of the Russo-Ottoman War from 1877 to 1878 and the Treaty of Berlin in 1878 north of the Chalkidiki to the west to a point on the Ionian coast. He justified his view with the fact that this required border line closed off the area with a majority Greek-speaking population to the north. Florina was or is north of this required demarcation, which was not implemented.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Florina had a population consisting of Greeks, Turks, Aromanians and (Slavic) Macedonians. In the 20th century, the Slavic Macedonian population in particular was repeatedly, and still is, the subject of political disputes regarding their nationality or nationality. The range of views extends from Slavic-speaking Greeks to Bulgarians with their own dialect to an independent ethnic group with an independent Slavic-Macedonian language. With these views or assignments, it becomes unclear - each for itself - whether the persons concerned would express themselves in free, safe and informal circumstances analogous to the views or in part or entirely against the view or assignment. In a comparative study with a critical evaluation of the sources, the following was noted on the subject of the various population statistics for the geographical region of Macedonia:

"Much has been said about the unreliability of the various populations statistics. The statistics usually reflect the various national claims and scholars who have espoused one particular national cause often insist on the validity of only those sources that support their own position, without discussing neither the methodology nor the circumstances the data were collected under. In many cases we are faced with a war of statistics by interested parties.

Much has been said about the unreliability of various demographic statistics. Statistics usually reflect different national claims and scholars advocating a particular national cause insist on the validity of only those sources which support their position without discussing the methodology or the circumstances under which the data were collected. In many cases we face a war of statistics by interested parties. "

In 1903, Florina had a population of 11,000, according to the New York Times. In 1916, according to a Greek census, the city of Florina had 3,576 Greeks, 6,227 Muslims (no differentiation according to ethnicity or sense of belonging) and 589 former exarchists, which added up to a total population of 10,392 inhabitants. In the same census, the following figures were determined for the prefecture of Florina (today: Prefectures of Florina and Kastoria): Greeks 71,367, Muslims (no differentiation) 27,858, former exarchists 39,764, total number 138,989. In 1923 members of the Turkish and Slavic-Macedonian population groups left the city of Florina. 407 members of the Slavic-Macedonian population group left Florina in 1923; how many of them came from the city of Florina itself is not clear.

The city of Florina had 12,562 inhabitants before the German attack on Greece in 1940. After the end of the Greek Civil War, the city of Florina had 12,343 inhabitants. This small loss of inhabitants - provided that the figures are correctly collected - is in contrast to the population development of the Florina prefecture over the same period. In 1940 this had 88,895 inhabitants, in 1950 there were 69,391 inhabitants. Between 1940 and 1950, during the Second World War and the German occupation of Florina from spring 1941 to autumn 1944 and especially during the Greek civil war from summer 1946 to summer 1949, part of the population fled the region (prefecture) of Florina. The extent to which the relatively unchanged population figures of the city of Florina reflect an unchanged population composition with regard to ethnicity and / or entries and exits without an ethnic background is not apparent. Possible conclusions, for example by analyzing the age group distribution, are not possible due to a lack of data. Based on the available figures for other regions affected by the civil war such as Kastoria and Grevena, an escape of the rural population or an evacuation of them to the city of Florina is very likely; the number of evacuated villages in the prefecture of Florina and the population decline in the prefecture with a relatively constant population of the city of Florina make such a population movement very likely.

The town of Trivouno in the area of today's municipality of Florina was certainly affected by the decline in population. It is located in the southwest corner of the municipality on the slopes of Verno (Vitsi) at an altitude of 1,156 m. In 1940 Trivouno had 629 inhabitants, in 1951 only 261 and 1961 only 229 inhabitants.

The majority of the population that had fled in relation to the entire Florina prefecture consisted of members of the Slavic Macedonians. According to official Greek information, there was no longer a Macedonian population in the region or prefecture and thus also in the city of Florina. This claim and / or finding is largely contested by human rights organizations and researchers outside Greece. Within Greece, too, opposition to this representation has been expressed since the 1990s in the form of a political party called Ouranio Toxo (literally rainbow , Macedonian: Vinozito ). The Ouranio Toxo party declares itself to be the political representative of the Slav-Macedonian minority in Florina and demands minority rights for the population group it represents, such as the use of Slav-Macedonian (or Macedonian, depending on your point of view). There is no reliable information about the size of the Macedonian (or Slav-Macedonian, depending on your point of view) minority in Florina. There is no recording by the Greek state, for example in the context of population censuses (most recently in 2001). In the 2004 elections to the European Parliament , the Ouranio Toxo party in the Florina prefecture received 1,204 votes. In the 2007 parliamentary elections in Greece , the party apparently did not take part in the election. The official results of the election for both the Prefecture of Florina and the Municipality of Florina show no votes for the Ouranio Toxo party.

During the German occupation of Florina between 1941 and 1944, Bulgaria, allied with the German Empire, expressed the wish that Florina and the Florina plain should fall to Bulgaria. The reason given for this request was that the population of this region was "purely Bulgarian".

In 1991 the municipality of Florina, based on the municipal boundaries of 2001, had a population of 14,873, in 2001 a population of 16,771, which corresponds to an increase in population of 12.8%. The population of the municipality of Florina grew considerably faster than in the prefecture of Florina (+ 3.05%).

Armenochori (Αρμενοχώρι)

The village of Armenochori was called Armenovo or Armenoro or Ermenovo (Αρμένοβο, Арменоро, Ерменово) until 1918 (depending on the source): by merging with the settlement Lazeni, the name that is in use today was officially used again, initially in the form of the Katharevousa name Armenochorion or Armenochorion Florinis (Αρμενοχώριον (Φλωρίνης)). In the 15th century (Ottoman period) it was also known as the Armenochor (Арменохор). In Bulgaria and the Republic of Macedonia, the name Armenovo (Арменоро) is still used.

Skopia (Σκοπιά)

The town of Skopia was called Ano Nevoliani (Άνω Νεβόλιανι) or Gorno Nevoljani (Γκόρνο Νεβόλιανι - Горно Неволјани) until 1928. On December 21, 1918, Skopia or Ano Nevoliani (Άνω Νεβολιάνη (Φλωρίνης)) became an independent community (Kinotita) (Kinotita).

Mesonisi (Μεσονήσι)

The village of Mesonisi is about 5 km east of the city of Florina at an altitude of 620 m. Until 1926, Mesonisi was called Lazeni (Λάζενι - Лажени). In Mesonisi, a line to Ano Kalliniki and on to Bitola in the Republic of Macedonia branches off the Florina-Amyndeo-Edessa-Thessaloniki railway line. This junction is currently not used.

politics

Mayor of the municipality of Florina has been Stefanos Papanastasiou from the conservative Nea Dimokratia party since 2002 . In the local elections in 2002, he prevailed in the first and decisive second ballot (runoff election with Christos Alembakis from the PASOK party ) with 43.85% and 56.42% of the vote. In the local elections in 2006 Papanastasiou won both the first round and the second round (runoff against the new candidate of PASOK) with 39.06 and 50.64% of the vote. The turnout in the local elections in 2006 was 42.28% (8,235 voters out of 19,477 eligible voters). In the municipal council of the municipality of Florina, the Nea Dimokratia is the strongest group with 13 out of 21 seats (2002: 13 seats); the second largest group is PASOK with 5 seats (2002: 6 seats).

In the local elections in 2010, the conservative Ioannis Voskopoulos (ND) prevailed in the runoff election with 55.27% in front of the independent candidate Emilios Aspridis and has since been mayor of the municipality. In the municipal council, his list includes 20 members, that of the defeated Aspridis received 8 seats, the PASOK list had four seats and the KKE had one seat.

In the 2007 parliamentary elections in Greece, the conservative party Nea Dimokratia in the municipality of Florina received an absolute majority with 52.39% of the vote (2004: 57.98%). Second place was the socialist or social democratic party PASOK with 33.05% of the vote (2004: 33.17%). The third strongest force was the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) with 5.51% of the vote (2004: 3.79%). The right-wing populist party LAOS received 3.72% of the votes (2004: 1.77%), the left-wing party SYRIZA received 3.25% of the votes (2004: 2.68%). All other parties received less than 2.0% of the vote. The share of votes of the Nea Dimokratia was higher in the municipality of Florina than in the prefecture (48.12%) or the whole of Greece (41.83%).

Economy, infrastructure and transport

economy

In the Ottoman period, wine was grown in Florina. Viticulture is hardly practiced today in the area of the municipality of Florina and is insignificant compared to the cultivation area of Amyndeo. The main economic pillar of the Florina prefecture was and is agriculture. The smaller towns in the Florina municipality are dominated by agriculture. The main crops are cereals. Florina is particularly known for its hot peppers, Piperies Florinis , and beans.

The city of Florina has been the administrative and market center for the surrounding villages since Ottoman times.

Infrastructure

Florina has the only hospital in the prefecture of the same name. In addition to the city of Florina, it also supplies the entire prefecture at the level of basic medical care for illnesses requiring inpatient treatment, comparable to a hospital with basic and standard care in Germany.

The city of Florina is the seat of the Pedagogical Faculty of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki: this faculty includes both the higher education of teachers and the higher education of educators for kindergartens and pre-schools. Three departments of the Technical University of West Macedonia (with headquarters in Kozani ) are also based in the city of Florina. The education system below the university level includes kindergartens, preschools, elementary schools (Dimotiko Scholio), grammar schools (comparable to the German secondary level I) and lyceums (comparable to the German secondary level II).

The city of Florina has a permanently manned guard of the professional fire brigade, which, in contrast to the municipal organization in Germany, is organized throughout Greece.

traffic

Traffic geography

Florina has always been a traffic junction in the southern part of the Bitola-Florina plateau, marketplace for the surrounding villages and towns and the administrative center for the region. Today the Florina Regional District Administration works here . Traffic routes from east to west and north to south cross here.

Streets

The settlement Herakleia Lynkestis was already of great importance in Roman times due to its location on the Via Egnatia , which ran from east ( Byzantium , Thessaloniki) to west ( Dyrrachion ) . The north-south connections from today's Skopje via Bitola to Thessaly and central and southern Greece were also available, but were significantly less important than the Via Egnatia, but gained in importance over time. In her travel reports, Ami Boué describes Florina as the intersection of these traffic axes.

Even today, in Florina - as in all of Greece - road traffic is the most important mode of transport. This applies to both individual and public transport. Two national roads and thus two European roads converge in Florina. From the west along the valley of the Sakouleva, the national road 2 ( European route 86 ) reaches Florina and leads in an easterly direction first to Vevi, then via a new route via Amyndeo to Edessa and then to Thessaloniki . From the north, national road 3 ( European route 65 ) reaches Florina from the Niki border crossing. Both national roads unite in the center of Florina to form a common route to the village of Amyndeo. The national road 3 leads from there to Kozani , Larisa , Lamia , central Greece and Athens . The national road 2 connects to the west on the one hand with Albania (border crossing Krystallopigi followed by continuation to Bilisht and Korça), on the other hand it connects Florina with Kastoria . From the national road 2, after passing the Pisoderi pass, a road leads to the Prespa lakes. The joint stretch of national roads 2 and 3 was completely re-routed east of Florina in order to increase its efficiency. For the national road 3 the same is pending from Florina to Niki to the Macedonian border.

Also KTEL use these roads for the public bus transport in Greece. Florina has regular bus connections with localities in the Florina Prefecture and beyond, such as Ptolemaida, Edessa, Kozani, Thessaloniki and Kastoria.

railroad

The railroad followed the historical traffic axes. On June 15, 1894 went railways Thessaloniki-Florina and Florina-Bitola in operation. A continuation of the railway line from Bitola (then: Monastir) to Skopje (then: Uskub) in a northerly direction did not exist at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century.

The station Florina was opening the track still in the village Mesonisi: At that time, a distance of 90 minutes. The branch from Mesonisi to Florina was not added until the beginning of the 20th century.

The cross-border line to Bitola ( Macedonia ) is out of service, but the Thessaloniki – Florina line is being served. Between 2002 and 2007, the line west of Edessa was closed due to modernization work. It is single-track and not electrified . At Amyndeo , a route branches off in a southerly direction to Kozani . The following are planned:

- a continuation of this southern branch from Kozani to Kalambaka in Thessaly , a direct connection to the railway network in Thessaly and central Greece;

- a connection between Florina and the Albanian railway network in Pogradec.

Given Greece's current financial situation, the chances of realizing such projects are not rated as high.

Long-distance hiking trails

The European long-distance hiking trails E4 and E6 lead through the municipality of Florina. The hiking trail E6, coming from the north-northwest from the Pisoderi Pass and Vigla, reaches the municipality of Florina and leads over the summit of the Vitsi (Vigla) to the village of Trivouno. To the east-northeast of this village, the E6 hiking trail meets the E6 European hiking trail, which leads from the south-southeast over the Verno ridge. Both the hiking trail E4 and the hiking trail E6 lead on a common route to the east-north-east from the Verno mountain ranges near Trivouno down into the valley in the western part of the town of Florina. From the city of Florina, the two hiking trails leave the city - again with a common route - and lead out of the municipality in an eastward arc. The monastery of Agios Markos from Byzantine times is passed.

Culture, sights and personalities

Culture

The city of Florina has two daily newspapers: Politis and Elefthero Vima and Vima tis Florinas, respectively . In addition to these daily newspapers, four weekly newspapers appear in Florina (in addition to the national Greek newspapers): Ethnos (founded in 1931, oldest weekly newspaper in Florina, not to be confused with the national Greek newspaper of the same name), Foni tis Florinis , Paratiritis and Anatropi . In addition to the local station of the national Greek national radio program ERA, Florina has other radio stations and transmitters: Akritikos FM 95.6, Radio Enigma 88 FM, Radio Florina 101.5 FM and Radio Ieros Chrysostomos 94.1 FM. The latter radio station is the radio station of the Florina diocese of the Greek Orthodox Church. Florina does not have its own television station: in the city there are, however, correspondent studios for the state television broadcaster ERT3 and the private television broadcaster West Channel.

The Greek director Theodoros Angelopoulos shot scenes for several of his films in Florina. The bishop of Florina A. Kantiotis excommunicated the director in 1991 because he saw the films that were anti-national and anti-church in his eyes, e. B. The Beekeeper and The Stork's Floating Step had turned in his diocese. However, the bishop's decision met with rejection both in the population of Florina and in Greek Orthodox church circles.

Attractions

Sights in the municipality of Florina are:

- Art Deco houses in the town of Florina (especially along the Sakoulevas River)

- Large cross on the hill of Agios Pandelimonas west of the city of Florina

- Archaeological site of the ancient city (Hellenistic period), southwest of the city of Florina

- Florina Archaeological Museum in the city of Florina

- Early historical burial site near Armenochori

- Agios Markos monastery from Byzantine times north of the city of Florina

- Old agricultural school in the city of Florina (today the seat of the Technical University)

- Byzantine Museum of the City of Florina

- Museum of Contemporary Art in the city of Florina

Sights in short distance (less than 20 km) of the municipality of Florina are:

- Prespa Lakes National Park

- Vigla ski area and Pisoderi pass

Personalities

- Necati Cumalı (* 1921, Florina † January 10, 2001, Istanbul, Turkey), writer from a Turkish family in Florina. Had to leave Florina with his family in 1923 because of the forced population exchange between Greece and Turkey.

- Şükrü Elçin (* 1912, Florina † October 27, 2008, Ankara, Turkey), Turkish historian. Had to leave Florina with his family in 1923 because of the forced population exchange between Greece and Turkey.

- Elisabeth Gertsakis (* 1954, Florina), Greek-Australian photographer, lives88 in Melbourne, Australia.

- Giorgos Lianis (born September 3, 1942, Florina), Greek politician (PASOK) and former Minister of Sports. From 1962–64 football player from Iraklis Thessaloniki.

- Sotiris Lioukras (* 1962, Florina), modern artist (installations).

- Sotir Kostov (born November 21, 1914, Florina - † October 1992, Sofia, Bulgaria), painter from a Bulgarian family in Florina.

- Vasilis Kyrkos (* 1942, Florina), painter.

- Pericles A. Mitkas (* 1962, Florina), Greek engineer and rector of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Results of the 2011 census at the National Statistical Service of Greece (ΕΛ.ΣΤΑΤ) ( Memento from June 27, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) (Excel document, 2.6 MB)

- ↑ a b National Statistical Service of Greece (EYSE): Census of March 18, 2001. Table 3. Population, area, population density and division into urban and rural as well as flat, semi-mountainous and mountainous areas. Average altitude. P. 151 ( Memento of September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ a b Geoclimate 2.1

- ↑ a b A. Oikonomidou Summer thermal comfort in traditional buildings of the 19th century in Florina, north-western Greece. Presented at International Conference “Passive and Low Energy Cooling for the Built Environment” May 2005, Santorini, Greece (in English)

- ^ Newspaper article in the Eleftheria newspaper of April 10, 1964, p. 8. Available online freely through the Greek National Library. ( Memento of the original from October 17, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (in Greek)

- ↑ Press release of the Athens News Agency (ANA) from March 30, 1997 (in English)

- ↑ Regional climatology for Florina by the Greek Meteorological Service (EMY) ( Memento of the original from October 6, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (in Greek)

- ↑ Anders, Birte: The Pre-Alpine Evolution of the Basement of the Pelagonian Zone and the Vardar Zone, Greece. Dissertation, Department of Chemistry, Pharmacy and Geosciences, Johannes-Gutenberg University Mainz. Mainz 2005. p. 22.

- ↑ a b Steenbrink, J .; Hilgen FJ; Krijgsman, W .; Wijbrans, JR; Meulenkamp, JE: Late Miocene to Early Pliocene depositional history of the intramontane Florina – Ptolemais – Servia Basin, NW Greece: Interplay between orbital forcing and tectonics. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. Volume 238, 2006 pp. 151-178. P. 152. doi : 10.1016 / j.palaeo.2006.03.023

- ^ A b Anders, Birte: The Pre-Alpine Evolution of the Basement of the Pelagonian Zone and the Vardar Zone, Greece. Dissertation, Department of Chemistry, Pharmacy and Geosciences, Johannes-Gutenberg University Mainz. Mainz 2005. p. Iii.

- ↑ Banitsiotou, ID; Tsapanos, TM; Margaris, VN; and Hatzidimitriou, PM: Estimation of the seismic hazard parameters for various sites in Greece using a probabilistic approach. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. Volume 4. 2004. pp. 399-405. P. 400.

- ↑ Banitsiotou, ID; Tsapanos, TM; Margaris, VN; and Hatzidimitriou, PM: Estimation of the seismic hazard parameters for various sites in Greece using a probabilistic approach. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. Volume 4. 2004. pp. 399-405. P. 404.

- ↑ a b Harry Thruston Peck: Lyncestis . In: Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1898. Accessible online through the Perseus Project at Tufts University. Accessed October 23, 2007 (in English)

- ↑ Harry Thruston Peck: Heraclēa . In: Harpers Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1898. Accessible online through the Perseus Project at Tufts University. Accessed October 23, 2007 (in English)

- ^ A b Central Israelite Council of Greece (ed.): Short History of the Jewish Communities in Greece. 3 edition. 2006. p. 97.

- ^ A b Kiel, Machiel : Remarks on the Administration of the Poll Tax (Cizye) in the Ottoman Balkans and Value of the Poll Tax Registers (Cizye Defterleri) for Demographic Research. Institut d'Etudes Balkaniques, Sofia. Etudes Balkaniques. Number 4. 1990. pp. 70-104. P. 95.

- ↑ Aarbakke, Vermund: Ethnic Rivalry and the Quest for Macedonia, 1870-1913. East European Monographs. Columbia University Press, New York 2003. p. 177. ISBN 0-88033-527-0

- ↑ Ami Boué: La Turquie d'Europe . Tome Troiziéme (Volume 3). S. 187. A. Bertrand, 1840

- ↑ Hacısalihoğlu, Mehmet: The Young Turks and the Macedonian Question (1890-1918). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2003. p. 34. ISBN 978-3-486-56745-8

- ↑ a b Hacısalihoğlu, Mehmet: The Young Turks and the Macedonian Question (1890-1918). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2003. p. 36. ISBN 978-3-486-56745-8

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article, March 11, 1854

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article, July 29, 1854

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article, January 21, 1878

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article from July 15, 1878 with contract text

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article, November 18, 1878

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article, August 19, 1879

- ↑ a b New York Times newspaper article, July 3, 1880

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article, December 4, 1880

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article, May 1, 1903

- ↑ a b New York Times newspaper article, August 3, 1903

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article, August 21, 1903

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article, August 22, 1903

- ↑ a b c New York Times newspaper article, Sept. 4, 1903, p. 4

- ^ New York Times newspaper article, Sept. 4, 1903, p. 2

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article, September 14, 1903, p. 1

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article, October 22, 1904, p. 7

- ^ New York Times newspaper article, Nov. 15, 1905, p. 7.

- ↑ a b c Hacısalihoğlu, Mehmet: The Young Turks and the Macedonian Question (1890-1918). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2003. p. 198. ISBN 978-3-486-56745-8

- ↑ Quoted from: Hacısalihoğlu, Mehmet: The Young Turks and the Macedonian Question (1890–1918). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2003. p. 198. ISBN 978-3-486-56745-8

- ↑ a b Meyer's Large Conversation Lexicon. A reference book of general knowledge. Sixth, completely revised and enlarged edition. Sixth volume: Earth food to Franzén. New imprint. Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig and Vienna 1906. S. 711. Available in digitized form at Zeno.org. Last accessed April 5, 2008.

- ^ A b c d e Hall, Richard C .: The Balkan Wars 1912-1913. A prelude to First World War. Routledge, New York 2000. pp. 60-61. ISBN 0-415-22946-4 .

- ↑ Boeckh, Katrin: From the Balkan Wars to the First World War: politics of small states and ethnic self-determination in the Balkans. Oldenbourg, Munich 1996. p. 58. ISBN 3-486-56173-1

- ↑ Boeckh, Katrin: From the Balkan Wars to the First World War: politics of small states and ethnic self-determination in the Balkans. Oldenbourg, Munich 1996. p. 94. ISBN 3-486-56173-1

- ↑ Boeckh, Katrin: From the Balkan Wars to the First World War: politics of small states and ethnic self-determination in the Balkans. Oldenbourg, Munich 1996. p. 219. ISBN 3-486-56173-1

- ↑ Emil Ludwig: The fight in the Balkans. Reports from Turkey, Serbia and Greece 1915 | 16 , Berlin (Fischer) 1916

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article from June 20, 1916 (in English, PDF file)

- ^ New York Times newspaper article from August 19, 1916 (in English, PDF file)

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article from August 21, 1916 (in English, PDF file)

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article from August 25, 1916 (in English, PDF file)

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article, September 9, 1916

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article from September 14, 1916 (in English)

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article from September 17, 1917

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article from September 19, 1916

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article from September 20, 1916

- ↑ Tsitselikis, Konstantinos: The Legal Status of Islam in Greece. The world of Islam. Volume 44, number 3. 2004. pp. 402-431.

- ↑ Kontogiorgi, Elisabeth: Population Exchange in Greek Macedonia. The rural settlement of refugees 1922-1930. Oxford Historical Monographs. Clarendon Press, Oxford 2006. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-19-927896-1 .

- ↑ Decree of the King of May 6, 1909. Published in the government newspaper (Efimeris tis Kyvernisis) FEK 125, Volume A, p. 7, of May 31, 1909. Available from the National Printing Office of Greece (Ethniko Typografio) (in Greek). Last accessed September 2, 2010.

- ↑ Kontogiorgi, Elisabeth: Population Exchange in Greek Macedonia. The rural settlement of refugees 1922-1930. Oxford Historical Monographs. Clarendon Press, Oxford 2006. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-19-927896-1 .

- ↑ Decree of the President of August 31, 1926. Published in the government newspaper (Efimeris tis Kyvernisis) FEK 346, Volume A, p. 2766, right column, item 21, of October 4, 1926. Available from National Printing Office of Greece (Ethniko Typografio) ( in Greek). Last accessed September 2, 2010.

- ↑ Decree of the President of August 20, 1927. Published in the government newspaper (Efimeris tis Kyvernisis) FEK 179, Volume A, p. 1262, right column, item 383, of August 30, 1927. Available from National Printing Office of Greece (Ethniko Typografio) ( in Greek). Last accessed September 2, 2010.

- ↑ Decree of the President of August 20, 1927. Published in the government newspaper (Efimeris tis Kyvernisis) FEK 179, Volume A, p. 1262, right column, point 385, of August 30, 1927. Available from National Printing Office of Greece (Ethniko Typografio) ( in Greek). Last accessed September 2, 2010.

- ↑ Decree of the President of July 19, 1928. Published in the government newspaper (Efimeris tis Kyvernisis) FEK 156, Volume A, p. 1233, left column, point 176, of August 8, 1928. Available at National Printing Office of Greece (Ethniko Typografio) ( in Greek). Last accessed September 2, 2010.

- ^ A b Manos, Ioannis: The Past as a Symbolic Capital in the Present: Practicing Politics of “Dance Tradition” in the Florina Region of Northwest Greek Macedonia. In: Keridis, Dimitris; Elias-Bursac, Ellen, Yatromanolakis, Nicholas (Eds.): New Approaches to Balkan Studies. The IFPA-Kokkalis Series on Southeast European Policy Volume 2. Brassey's, 2003. p. 29. ISBN 1-57488-724-6

- ↑ a b Kurt von Tippelskirch: History of the Second World War . Athenäum-Verlag, 1959. p. 120

- ^ A b Military History Research Office (ed.): Germany and the Second World War . Oxford University Press , 1998. pp. 499 ff. ISBN 978-0-19-822884-4

- ^ Kurt von Tippelskirch: History of the Second World War . Athenäum-Verlag, 1959. p. 153

- ↑ Military History Research Office (Ed.): Germany and the Second World War . Oxford University Press, 1998. p. 504. ISBN 978-0-19-822884-4

- ↑ Foreign Office: Files on German Foreign Policy, 1918–1945 . Self-published, 1995. p. 525

- ↑ a b Foreign Office: Files on German Foreign Policy, 1918–1945 . Self-published, 1995. p. 585

- ^ Gerhard Schreiber: The Italian military internees in the German sphere of influence: 1943 to 1945 . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 1990. p. 162. ISBN 978-3-486-55391-8

- ^ Gerhard Schreiber: The Italian military internees in the German sphere of influence: 1943 to 1945 . Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 1990. p. 255. ISBN 978-3-486-55391-8

- ^ Helmuth Greiner, Percy Ernst Schramm: War Diary of the High Command of the Wehrmacht (Wehrmacht Command Staff) 1940–1945 . Bernard & Graefe, 1965. pp. 445, 474

- ^ Shrader, Charles R .: The Withered Vine. Logistics and the communist insurgency in Greece, 1945-1949. Praeger / Greenwood, Westport 1999. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-275-96544-0

- ↑ Newspaper article in the Eleftheria newspaper of September 3, 1946, page 4, middle column

- ↑ Newspaper article of the newspaper Eleftheria of January 8, 1947, page 4, right column

- ↑ Koliopoulos, Giannis S .; Koliopoulos, John S .: Plundered Loyalties: Axis Occupation and Civil Strife in Greek West. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, London 1999. p. 278. ISBN 978-1-85065-381-3

- ↑ Newspaper article in the Eleftheria newspaper from May 31, 1947, page 1, left column

- ↑ Newspaper article of the newspaper Eleftheria from August 20, 1947, page 1, right column

- ↑ Newspaper article of the newspaper Eleftheria of October 26, 1948, page 6, right column

- ^ Shrader, Charles R .: The Withered Vine. Logistics and the communist insurgency in Greece, 1945-1949. Praeger / Greenwood, Westport 1999. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-275-96544-0

- ↑ Newspaper article in the Eleftheria newspaper from February 15, 1949, page 1, left column

- ↑ New York Times newspaper article, Feb.15 , 1949, p. 8

- ↑ a b Shrader, Charles R .: The Withered Vine. Logistics and the communist insurgency in Greece, 1945-1949. Praeger / Greenwood, Westport 1999. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-275-96544-0

- ↑ Newspaper article in the Eleftheria newspaper from February 18, 1949, page 3, middle column

- ^ Shrader, Charles R .: The Withered Vine. Logistics and the communist insurgency in Greece, 1945-1949. Praeger / Greenwood, Westport 1999. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-275-96544-0

- ↑ Newspaper article in the Eleftheria newspaper from May 15, 1949, page 1, right column

- ↑ Newspaper article in The Times newspaper, August 15, 1949, p. 3

- ↑ Koliopoulos, Giannis S .; Koliopoulos, John S .: Plundered Loyalties: Axis Occupation and Civil Strife in Greek West. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, London 1999. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-85065-381-3

- ↑ Newspaper article in The Times newspaper, August 23, 1949, p. 3

- ↑ a b c d Poulton, Hugh: Who are the Macedonians? C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, London 2000. p. 163. ISBN 1-85065-534-0

- ↑ Hinrich-Matthias Geck: The Greek labor migration: An analysis of its causes and effects . Hanstein, 1979. p. 101. ISBN 978-3-7756-6932-0

- ↑ Poulton, Hugh: Who are the Macedonians? C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, London 2000. p. 171. ISBN 1-85065-534-0

- ↑ Ami Boué. La Turquie d'Europe. Tome Deuziéme (Volume 2). S. 5. A. Bertrand, 1840

- ^ Heinrich Barth: Journey through the interior of European Turkey . D. Reimer, 1864. p. 154