Salt March

The Salt Satyagraha, also known as the Salt March to Dandi, was an act of non-violent protest against the British salt tax in colonial India from March 12, 1930, to April 6, 1930. Mahatma Gandhi along with his followers, walked from Sabarmati Ashram to Dandi, Gujarat to make salt, with growing numbers of Indians joining him along the way. The march was the first organized action after India's Declaration of Independence and sparked large scale acts of civil disobedience against the British Raj by millions of Indians.[1]

Declaration of Independence

At midnight on December 31 1929, the Indian National Congress raised the tricolour flag of India on the banks of the Ravi at Lahore. The Indian National Congress, led by Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, issued the Declaration of Independence five days earlier. The declaration included the readiness to withhold taxes, and the statement:

We believe that it is the inalienable right of the Indian people, as of any other people, to have freedom and to enjoy the fruits of their toil and have the necessities of life, so that they may have full opportunities of growth. We believe also that if any government deprives a people of these rights and oppresses them the people have a further right to alter it or abolish it. The British government in India has not only deprived the Indian people of their freedom but has based itself on the exploitation of the masses, and has ruined India economically, politically, culturally and spiritually. We believe therefore, that India must sever the British connection and attain Purna Swaraj or complete independence.[2]

The Congress Working Committee gave Gandhi the responsibility for organizing the first act of civil disobedience, with Congress itself ready to take charge after Gandhi's expected arrest.[3] Gandhi's idea was to begin civil disobedience with a satyagraha aimed at the salt tax. Some Congress leaders thought that salt was a paltry way to launch a momentous fight with the British, but Gandhi had his reasons for choosing the salt tax.[4] The salt tax was a deeply symbolic choice, since salt was used by nearly everyone in India. It represented 8.2% of the British Raj tax revenue, and most significantly hurt the poorest Indians the most.[5] Gandhi felt that this protest would dramatize Purna Swaraj in a way that was meaningful to the lowliest Indians. He also reasoned that it would build unity between Hindus and Muslims by fighting a wrong that touched them equally.[6]

The British laws declared that the sale or production of salt by anyone but the British government was a criminal offence. Salt was readily available to those living on the coast, but instead of being allowed to collect it for their own use, people were forced to purchase it from the colonial government. So Gandhi's decision to protest this tax met the important criterion of appealing across regional, class, religious, and ethnic boundaries.

Satyagraha

Mahatma Gandhi had a long-standing commitment to non-violent civil disobedience as the basis for achieving Indian independence, along with many members of the Congress Party.[7] His first significant attempt in India at leading mass civil disobedience was the Non-cooperation movement from 1920-1922. Even though it succeeded in raising millions of Indians in protest against the British created Rowlatt Acts, violence broke out and Gandhi suspended the protest. He blamed himself for not preparing people properly in the ways of satyagraha.

Satyagraha is a synthesis of the Sanskrit words "Agraha" (holding firmly to) and "Satya" (truth). For Gandhi, satyagraha went beyond mere "passive resistance", and became strength in practicing non-violent methods. In his words:

I often used “passive resistance” and “satyagraha” as synonymous terms: but as the doctrine of satyagraha developed, the expression “passive resistance” ceases even to be synonymous, as passive resistance has admitted of violence as in the case of suffragettes and has been universally acknowledged to be a weapon of the weak. Moreover, passive resistance does not necessarily involve complete adherence to truth under every circumstance. Therefore it is different from satyagraha in three essentials: Satyagraha is a weapon of the strong; it admits of no violence under any circumstance whatever; and it ever insists upon truth. I think I have now made the distinction perfectly clear.[8]

March to Dandi

On February 5, newspapers reported that Gandhi would begin civil disobedience by defying the salt laws. Before he broke the law, however, Gandhi appealed to the Viceroy, Lord Irwin, in an effort to have the salt tax amended. On March 2, 1930 Gandhi wrote:

If my letter makes no appeal to your heart, on the eleventh day of this month I shall proceed with such co-workers of the Ashram as I can take, to disregard the provisions of the Salt Laws. I regard this tax to be the most iniquitous of all from the poor man's standpoint. As the Independence movement is essentially for the poorest in the land, the beginning will be made with this evil.[9]

In addition, Gandhi told Irwin that the exploitation by the British "seems to be designed to crush the very life out of" its victims.[10] Irwin did not take the threat of a salt protest seriously, writing to London that "At present the prospect of a salt campaign does not keep me awake at night."[11] After the Viceroy ignored the letter and refused to meet with Gandhi, the march was set in motion.[12]

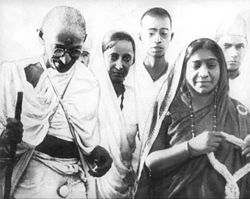

On March 12, 1930, Gandhi and 78 male satyagrahis set out on foot for the coastal village of Dandi, Gujarat, nearly 400 km. from their starting point in Sabarmati. The 23 day march would pass through 4 districts and 48 villages. It was extremely organized, with the exact route and events at each village scheduled and publicized in Indian and foreign press.[13] As they entered each village, crowds greeted the marchers, beating drums and cymbals. Gandhi gave speeches attacking the salt tax as inhuman, and the salt satyagraha as a "poor man's battle." Each night they slept in the open, asking of the villagers nothing more than simple food and a place to rest and wash. Gandhi felt that this would bring the poor into the battle for independence, necessary for eventual victory.[14]

Thousands of satyagrahis and leaders like Sarojini Naidu joined him. Every day, more and more people joined the march. At Surat, they were greeted by 30,000 people. When they reached the railhead at Dandi, more than 50,000 were gathered. Gandhi gave interviews and wrote articles along the way. Foreign journalists made him a household name in Europe and America.[15]

Upon arriving at the seashore on the 5th of April, Gandhi was interviewed by an Associated Press reporter. He stated:

God be thanked for what may be termed the happy ending of the first stage in this, for me at least, the final struggle of freedom. I cannot withhold my compliments from the government for the policy of complete non interference adopted by them throughout the march .... I wish I could believe this non-interference was due to any real change of heart or policy. The wanton disregard shown by them to popular feeling in the Legislative Assembly and their high-handed action leave no room for doubt that the policy of heartless exploitation of India is to be persisted in at any cost, and so the only interpretation I can put upon this non-interference is that the British Government, powerful though it is, is sensitive to world opinion which will not tolerate repression of extreme political agitation which civil disobedience undoubtedly is, so long as disobedience remains civil and therefore necessarily non-violent .... It remains to be seen whether the Government will tolerate as they have tolerated the march, the actual breach of the salt laws by countless people from tomorrow. I expect extensive popular response to the resolution of the Working Committee (of the Indian National Congress).[16]

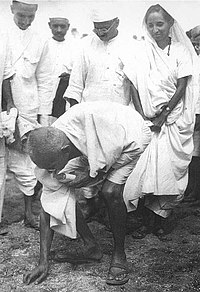

The following morning, after a prayer, Gandhi raised a lump of salty mud and declared, "With this, I am shaking the foundations of the British Empire."[17] He then boiled it in seawater, producing illegal salt. He implored his thousands of followers to likewise begin making salt along the seashore, "wherever it is convenient" and to instruct villagers in making illegal salt.[18]

Civil disobedience after the march

Mass civil disobedience spread throughout India as millions broke the salt laws by making salt or buying illegal salt.[19] Salt was sold illegally all over the coast of India. A pinch of salt made by Gandhi himself sold for 1,600 rupees, (equivalent to $750 dollars at the time). In reaction, the British government incarcerated over sixty thousand people by the end of the month.[20]

What had begun as a Salt Satyagraha quickly grew into a mass Satyagraha.[21] British cloth and goods were boycotted. Unpopular forest laws were defied in Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Central Provinces. Gujarati peasants refused to pay tax, under threat of losing their crops and land. In Midnapore, Bengalis took part by refusing to pay the chowkidar tax.[22] The British responded with more laws, declaring the Congress and its associate organizations illegal. None of those measures slowed the civil disobedience movement.[23]

In Peshawar, satyagraha was led by a Muslim Pashto disciple of Gandhi, Ghaffar Khan, who had trained a 50,000 member army of non-violent activists called Khudai Khidmatgar.[24] On April 23, 1930, Ghaffar Khan was arrested. A crowd of Khudai Khidmatgar gathered in Peshawar's Kissa Khani [Storytellers] Bazaar. The British opened fire with machine guns on the unarmed crowd, killing an estimated 200-250.[25] The Pashtun satyagrahis acted in accord with their training in non-violence, willingly facing bullets as the troops fired on them.[26] One British Indian Army regiment, troops of the renowned Royal Garhwal Rifles, refused to fire at the crowds. The entire platoon was arrested and many received heavy penalties, including life imprisonment.[27]

The civil disobedience in 1930 marked the first time women became mass participants in the struggle for freedom. Thousands and thousands of women, from large cities to small villages, became active participants in satyagraha.[28] Gandhi had asked that only men take part in the salt march, but eventually women began manufacturing and selling salt throughout India. Usha Mehta, an early Gandhian activist, remarked that "Even our old aunts and great-aunts and grandmothers used to bring pitchers of salt water to their houses and manufacture illegal salt. And then they would shout at the top of their voices: "We have broken the salt law!" "[29]

Gandhi himself avoided further active involvement after the march, though he stayed in close contact with the developments throughout India. He created a temporary ashram near Dandi. On the night of May 4th, he was sleeping on a cot in a mango grove. Shortly after midnight the District Magistrate of Surat drove up with two Indian officers and thirty heavily-armed constables.[30] He was arrested under an 1827 regulation calling for the jailing of people engaged in unlawful activities, and held without trial near Pune.[31]

Civil disobedience continued until early 1931, when Gandhi was finally released from prison and held talks with Irwin. It was the first time the two held talks on equal terms.[32] The march also drew the attention of the world. Time magazine declared Gandhi its 1930 Man of the Year, comparing Gandhi's march to the sea "to defy Britain's salt tax as some New Englanders once defied a British tea tax."[33]

Congress leaders decided to end satyagraha as official policy in 1934. Even though British authorities gained some semblance of control by the mid 1930's, world opinion increasingly recognized the claims of Gandhi and the Congress Party for independence.[34] Nehru felt that satyagraha had a lasting impact:

Of course these movements exercised tremendous pressure on the British Government and shook the government machinery. But the real importance, to my mind, lay in the effect they had on our own people, and especially the village masses....Non-cooperation dragged them out of the mire and gave them self-respect and self-reliance....They acted courageously and did not submit so easily to unjust oppression; their outlook widened and they began to think a little in terms of India as a whole....It was a remarkable transformation and the Congress, under Gandhi's leadership, must have the credit for it.[35]

Re-enactment in 2005

To commemorate the Great Salt March, the Mahatma Gandhi Foundation proposed a re-enactment on the 75th anniversary. The event was known as the "International Walk for Peace, Justice and Freedom". Mahatma Gandhi's great-grandson Tushar Gandhi and several hundred fellow marchers followed the same route to Dandi and planned to take a similar amount of time to walk it. The start of the march on March 12, 2005 in Ahmedabad was attended by Sonia Gandhi (no familial relations), Chairperson of the National Advisory Council, as well as nearly half of the Indian cabinet, many of whom walked for the first few kilometres. The commemoration ended on April 7, with the participants finally halting at Dandi on the night of April 5.

A series of commemorative stamps issued on the centenary of Dandi March. Denomination INR 5, Date of Issue: April 6, 2005.

Notes

- ^ Gandhi & Dalton, 1996, p. 72.

- ^ Wolpert, p. 204.

- ^ Ackerman & DuVall, p. 83.

- ^ Ackerman & DuVall, p. 83.

- ^ Gandhi & Dalton, 1996, p. 72.

- ^ Ackerman & DuVall, p. 83.

- ^ Ackerman & DuVall, p. 108.

- ^ Gandhi, 1994, “Letter to Mr. ——” 25 January 1920, p. 350.

- ^ Gandhi & Jack, 1994, p. 236.

- ^ Gandhi & Dalton, 1996, p. 72.

- ^ Ackerman & DuVall, p.84.

- ^ Majmudar, p. 184.

- ^ Ackerman & DuVall, p.85.

- ^ Ackerman & DuVall, p. 86.

- ^ Ackerman & DuVall, p. 86.

- ^ Gandhi & Jack, 1994, p. 238-239.

- ^ Gandhi & Dalton, 1996, p. 72.

- ^ Gandhi & Jack, 1994, p. 240.

- ^ Gandhi & Dalton, 1996, p. 72.

- ^ Gandhi & Jack, 1994, p. 238-239.

- ^ Habib, p. 57.

- ^ Habib, p. 57.

- ^ Habib, p. 57.

- ^ Habib, p. 55.

- ^ Habib, p. 56.

- ^ Johansen, p. 62.

- ^ Habib, p. 56.

- ^ Chatterjee, p. 41.

- ^ Hardiman, p. 113.

- ^ Gandhi & Jack, 1994, p. 244-245.

- ^ Riddick, p. 108.

- ^ Gandhi & Dalton, 1996, p. 73.

- ^ Time Magazine (1931-01-05). "Man of the Year, 1930". Time. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- ^ Johnson, p. 37.

- ^ Johnson, p. 37.

References

- Ackerman, Peter (2000). A Force More Powerful: A Century of Nonviolent Conflict. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0312240503.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Chatterjee, Manini (Jul. - Aug., 2001). "1930: Turning Point in the Participation of Women in the Freedom Struggle". Social Scientist. 29, No. 7/8: pp. 39-47.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - Dalton, Dennis (1993). Mahatma Gandhi: Nonviolent Power in Action. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231122373.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Habib, Irfan (Sep. - Oct., 1997). "Civil Disobedience 1930-31". Social Scientist. 25, No. 9/10: pp. 43-66.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - Gandhi, Mahatma (1994). The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of India.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Gandhi, Mohandas K. (1962). The Essential Gandhi. New York: Vintage. ISBN 1-4000-3050-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Gandhi, Mahatma (1994). The Gandhi Reader: A Sourcebook of His Life and Writings. Grove Press. ISBN 0802131611.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Gandhi, Mahatma (1996). Selected Political Writings. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 0872203301.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Hardiman, David (2003). Gandhi in His Time and Ours: The Global Legacy of His Ideas. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231131143.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Johansen, Robert C. (1997). "Radical Islam and Nonviolence: A Case Study of Religious Empowerment and Constraint Among Pashtuns". Journal of Peace Research. Vol. 34, No. 1: pp. 53-71.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help) - Johnson, Richard L. (2005). Gandhi's Experiments With Truth: Essential Writings By And About Mahatma Gandhi. Lexington Books. ISBN 0739111434.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Majmudar, Uma (2005). Gandhi's Pilgrimage Of Faith: From Darkness To Light. New York: SUNY Press. ISBN 0791464059.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Riddick, John F. (2006). The History of British India: A Chronology. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313322805.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Wolpert, Stanley (2001). Gandhi's Passion: The Life and Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi. Oxford University Press. ISBN 019515634X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Wolpert, Stanley (1999). India. University of California Press. ISBN 0520221729.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

External links

- Eyewitness Account of Gandhi's Salt March at www.nrifm.com

- Salt march slide pack (Rediff.com)

- The Salt March

- Gandhi's 1930 march re-enacted (BBC News)

- Gandhi salt march re-enacted (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)

- Gandhi's Salt Satyagraha March Movie - Gandhi leads a campaign to extract salt from ocean water.

- Now, Dandi looks westward for help (TOI)