Äskulapstein (Godesburg)

The Godesberger Äskulapstein is a Roman votive stone that was found on the Godesburg in the 16th century . It is now in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn .

Description and history

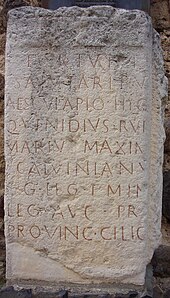

The stone may have served as a Weihaltar. It was carved from Drachenfels - Trachyte , is 110 cm high, 65 cm wide and 39 cm deep and bears the inscription:

Fortunis / Salutaribu [s] / Aesculapio / Hyg [iae] / Q (uintus) Venidius Ruf [us] / Mariu [s] Maxim [us] / [L (ucius)] Calvinianu [s] / [le] g (atus ) leg (ionis) I Min (erviae) / leg (atus) Aug (usti) pr (o) [pr (aetore)] / provinc (iae) Cilic [iae] / d (onum) [d (edit)];

so he is consecrated to the healing gods Aesculapia and Hygieia .

The founder of the stone, Quintus Venidius Rufus Marius Maximus Lucius Calvinianus , had served as legatus in the Legio I Minervia and at the time of the foundation was Legatus Augusti pro Praetore of the province of Cilicia . He is also mentioned in an inscription from 198, there as "Legatus Augusti pro Praetore praeses provinciae Syriae Phoenic."

J. Freudenberg concluded from this consecration stone for health deities "that the Romans had already visited Godesberg temporarily as a curort not only because of its wonderful and healthy location, but also because of its Draisch or Sauerbrunnen, perhaps also for the use of cold water baths." He was confirmed himself through the discovery of traces of Roman borders at the Draischbrunnen . Johanna Schopenhauer expressed himself similarly as early as 1828: “An ancient Roman votive stone consecrated to the Aesculapian, which was excavated in the sixteenth century on the Godesberg and is now preserved in Bonn in the Museum of Rhenish-Westphalian Antiquities, proves that the Romans even used the healing spring Godesberg, who probably had more important powers then than in our day. "

This theory is also supported by later scientists: According to Tanja Potthoff, it is not certain whether the stone that had previously been walled up in the castle was found in the rubble after it was blown up in 1583 or in the vicinity of the source there. In any case, Potthoff assumes that it belonged to a previously unknown Roman spring shrine that was located in Godesberg or the surrounding area.

The Godesburg had a previous building from the 3rd or 4th century; a burgus with foundations that contained opus caementitium . Remains of this rectangular building are preserved in the base of the medieval keep . What the building was used for is unknown, but the consecration stone was used as an argument for the fact that it was a high altitude shrine. However, since the stone is much older than the remains of the building, this argument is not very valid. According to another theory, the structure was a Roman watchtower.

A copy of the consecration stone is on the Godesburg.

literature

- Alfred Wiedemann : History of Godesberg and its surroundings , Bad Godesberg 1930, pp. 5–6.

- Walter Haentjes: The Aeskulapstein von der Godesburg , in: Godesberger Heimatblätter 17, 1979, pp. 5-15.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Walther Zimmermann: The art monuments of the Rhineland. Supplement 20, 1974, p. 95.

- ↑ CIL XIII, 7994 .

- ↑ J. Freudenberg, Ein unedirter Matronenstein from Godesberg , in: Yearbooks of the Verein von Alterthumsfreunden im Rheinlande , 44–45, 1868, pp. 81–84, here pp. 83–84 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Johanna Schopenhauer, The old Godesberg castle . See also the Baedeker entry from 1864.

- ^ Tanja Potthof: The Godesburg. Archeology and building history of a castle in the Electorate of Cologne , dissertation Munich 2009, p. 4 (PDF; 1.8 MB).

- ↑ For the theories about the late antique building see Tanja Potthoff, Vom Burgus zur Burg? The example of Godesberg , in: Olaf Wegener (Hrsg.): The contested place - from antiquity to the Middle Ages (= supplements to medieval studies 10), Peter Lang, Frankfurt a. a. 2008, ISBN 978-3631575574 , pp. 2013 ff., Here pp. 204–205.