Draischbrunnen

The Draisch or Draitschbrunnen is a fountain in the Bad Godesberg district of Bonn .

history

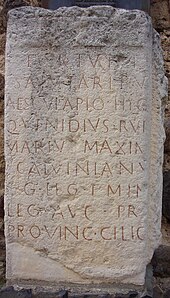

The Godesberg doctor FJ Schwann reported on the history of the fountain in 1865, saying that it had already been used in Roman times . As evidence, he used the Aesculapian stone from Godesburg , which a Roman legate donated around 198 AD and which was found again in the 16th century. The location of this stone and the circumstances surrounding it are, however, somewhat controversial.

Elector Clemens August became aware of the fountain around the middle of the 18th century . He sent for experts from Spa to investigate the various sources from which it appeared to have been fed, and to erect a wooden enclosure. However, after the strangers were suspected of supplying "wild water" to the well, they were sent away again. The elector died soon after these first examinations. Around 1789, the Bonn chemist Ferdinand Wurzer was made aware of the fountain and initiated new investigations. After the results were favorable, Elector Maximilian Franz made Godesberg a health resort. He had the spring grasped and the necessary buildings and facilities laid out after he had bought the land around the well. Wurzer's investigations had revealed 14 springs that together made up the so-called old well. However, after attempts had been made to make the fountain particularly useful by means of an extremely high socket, it dried up.

As a result, excavations were quickly made in the area, in which two other sources were found. They were combined and now formed the new Draischbrunnen. The well and the health resort gained some prestige, but after the invasion of the French revolutionary army and the elector's flight in 1794, the operation came to an end again. According to Schwann, the guests of the new era had less of a need “to find their health again in the green hall of the Draisch or to strengthen the weakened one,” but rather they obeyed “rather the instinct, the passions of the game at the green table of the redoubt to satisfy". It was not until 1818, after the establishment of the University in Bonn that gambling in Godesberg had been abolished, that the fountain again met with greater interest; However, it was still some time before it received a new version in 1830 and a "completely tasteless zinc roof resting on iron bars". However, the quality of the water after the replacement bore could not be compared with the previous one, and little else was done to attract and entertain the spa guests. In 1856 the Balneologische Zeitung complained: “There is never talk of balls here, and concerts rarely. The sensual nature lover has to compensate for all the loud amusements the charm of the landscape. I fail to describe them to you. The mayor, Baron von Buggenhagen, had seriously intended to make the spring usable again [...] When asked whether a new and deeper version of the spring could restore the former power to the water, [...] ] the answer has been given that the rock from which the spring comes is so often fissured that no favorable result can be expected. "

In 1864, the community of Godesberg, under its mayor Carl August von Groote, acquired fountains and land from the royal government. Efforts were made to finally clarify the various sources that flowed together in the well, and the entire area between the old and the new Draischbrunnen was dug up to the layer of slate underneath . It was found that at greater depths the water was richer in iron and salt, whereupon a borehole was driven to a depth of 93 feet below the previous well bottom. This itself was about 18 feet below the ambient level. It was assumed that the good quality of the water was not only due to this slate layer, but also to the graywacke layers above it with and without basalt inclusions and finally to the volcanic rock and basalt deposits in the area, such as the Gudenauer valley. The highly carbonated water was considered to be beneficial for a wide variety of evils and was viewed as unique in Germany: "So mineral water is the middle link between alkaline and muriastic iron-acid like Germany has no other," said Georg Ludwig Ditterich in 1867.

When use increased again, a line was laid to the city park, which had been laid out in 1890. There the water could be drunk in a spring temple. Godesberg developed into one of the most renowned health resorts before the First World War , also through the export of Draischbrunnen water . In 1926 Godesberg became a bath, in 1935 a town. After the Second World War , the bathing business was resumed, but no longer flourished and finally came to a complete standstill. However, the mineral water continued to be sold successfully; In 1962, the Kurfürstenquelle, another spring was drilled in Bad Godesberg. In 1970 a drinking hall was built, in which the water from the Kurfürstenquelle is served, in 1977 a pavilion was added on Brunnenallee, where both mineral waters are available.

literature

- FJ Schwann, The Godesberger Mineralbrunnen Draisch after the new drilling of 1865 , Godesberg 1865

- Georg Schwedt : Ferdinand Wurzer and the founding of the Godesberger Gesundbrunnen. In: Association for Home Care and Local History Bad Godesberg e. V. (Ed.): Godesberger Schriften des Verein für Heimatpflege und Heimatgeschichte Bad Godesberg e. V. Bonn 2015, ISBN 978-3-9816445-1-7 .

- Martin Ammermüller : The new construction of the Draitsch fountain by the VHH - 225 years after its inauguration. In: Association for Home Care and Local History Bad Godesberg e. V. (Hrsg.): Annual volume 2015 of the Association for Home Care and Local History Bad Godesberg e. V. (= Godesberger Heimatblätter. Volume 53), Bonn 2015, ISSN 0436-1024 , pp. 7–32. [not yet evaluated for this article]

Web links

- The Draitschbrunnen in the source atlas (with partly different data from Schwann)

Individual evidence

- ↑ In the older sources, for example here , the fountain is apparently mostly called Draischbrunnen, in more recent sources the spelling Draitschbrunnen is common.

- ^ FJ Schwann, The Godesberger Mineralbrunnen Draisch after the new drilling of 1865 , Godesberg 1865, p. 6

- ↑ Tanja Potthof, Die Godesburg - Archeology and Building History of an Electoral Cologne Castle , Diss. Munich 2009, p. 4 (PDF; 1.8 MB)

- ↑ Lauterbach, Irene R .: Three generations of Wurzer in the 18th and 19th centuries. The autobiographies of Joseph and Ferdinand Alexander Wurzer. Publisher: Peter Lang, Frankfurt / Main 2015, p. 181 f.

- ↑ Schwann 1865, p. 8 f.

- ↑ Schwann 1865, p. 10

- ↑ Schwann 1865, p. 14

- ↑ Schwann 1865, p. 16

- ↑ Louis Spengler (ed.), Balneologische Zeitung. Correspondence sheet of the German Society for Hydrology , Volume 3, Wetzlar 1856, p. 249

- ↑ Schwann 1865, p. 21

- ↑ Georg Ludwig Ditterich, Clinical Balneology , Volume 3, 1867, Appendix, p. 17

- ↑ Source Atlas

Coordinates: 50 ° 40 ′ 48.93 " N , 7 ° 8 ′ 59.1" E