Chord-scale theory

The chord-scale theory (AST for short) is an essential part of modern harmony theory . In the AST, chords and chord scales form a functional unit. While the notes of the chord sound simultaneously, the scale specifies the notes that can be played for this chord. This view is oriented towards the application of music.

The AST describes the tonal potential that lies in a chord or in a chord progression. Based on the close interrelationship that exists between chord and scale, it offers the musician a system for assigning the appropriate scales ( scales ) to chords (and vice versa). The AST was significantly expanded and further developed at the Berklee College of Music .

introduction

Music changes and with it, listening habits change. In many lead sheets only chords are noted. Each chord is viewed as an individual result and interpreted vertically. An accompaniment or improvisation does not only live on chord tones. Therefore, nowadays people tend to think horizontally and assign each chord its own scale or chord scale.

Relationship between chord and chord scale

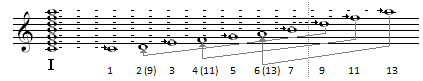

In the AST, seventh chords (four notes) determine the harmony. The chord scale is created by adding three further layers of thirds to the seventh chord and shifting these down one octave. These three further thirds, so-called tension or tension or option tones, depend on the function or level of the chord and thus on the key. In this way, the chord scale provides the notes that can be played along with that chord.

This relationship can best be illustrated using an example. In the theory of degrees , the notes of a scale, which provides the tonal material of a piece, are numbered consecutively from the root note with Roman numerals. A seventh chord or four-note chord is formed at each level. The following picture illustrates this using the C major scale.

The AST usually ascribes the following functions to the individual chords in cadences:

| step | major | C major | function |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. | Imaj7 | Cmaj7 | Tonic |

| II | II-7 | D-7 | Subdominant |

| III | III-7 | E-7 | Tonic |

| IV | IVmaj7 | Fmaj7 | Subdominant |

| V | V7 | G7 | Dominant |

| VI | VI-7 | A-7 | Tonic |

| VII | VII-7 (b5) | B-7 (b5) | tends to be dominant |

The notation chosen here for chords is based on the chord symbols often found in AST. "-" stands for minor, the note B for the German H.

The chord scale belonging to the seventh chord is created by adding three layers of thirds over it. This is illustrated in the following picture using the CMaj7 chord at level I above. The now 7-part chord is then transferred horizontally into a scale (dashed). In a further step, the chord steps 9, 11, 13 are pressed into the lower octave space (gray).

The Ionic chord scale is created. The seven notes of the scale are ladder.

If you apply this procedure to each step of the C major scale, you get the following chord scales for the step chords.

| step | major | C major | Chord scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. | Imaj7 | Cmaj7 | C ionic |

| II | II-7 | D-7 | D Doric |

| III | III-7 | E-7 | E Phrygian |

| IV | IVmaj7 | Fmaj7 | F lydian |

| V | V7 | G7 | G Mixolydian |

| VI | VI-7 | A-7 | Aeolian |

| VII | VII-7 (b5) | B-7 (b5) | B locrian |

The chord scales provide 7 scale tones that can be played melodically or one after the other for the corresponding chords. In contrast, not all scale tones are suitable for playing chords at the same time. The unsuitable tones are referred to as avoid tones of a scale. All tension tones of the 7 scales are ladder.

If you build up the scales for all major and minor keys in this way, a comprehensive system results, which is shown in the following table using the major scales. You can see that in the major key, every scale is unique. C Mixolydian is synonymous with the fifth degree in F major.

| Ionic | Doric | Phrygian | Lydian | mixolydian | Aeolian | locrian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | |

| Imaj7 | II-7 | III-7 | IVmaj7 | V7 | VI-7 | VII-7 (b5) | |

| C major | Cmaj7 | D-7 | E-7 | Fmaj7 | G7 | A-7 | B-7 (b5) |

| G major | Gmaj7 | A-7 | B-7 | Cmaj7 | D7 | E-7 | F # -7 (b5) |

| D major | Dmaj7 | E-7 | F # -7 | Gmaj7 | A7 | B-7 | C # -7 (b5) |

| A major | Amaj7 | B-7 | C # -7 | Dmaj7 | E7 | F # -7 | G # -7 (b5) |

| E major | Emaj7 | F # -7 | G # -7 | Amaj7 | B7 | C # -7 | D # -7 (b5) |

| B major | Bmaj7 | C # -7 | D # -7 | Emaj7 | F # 7 | G # -7 | A # -7 (b5) |

| F # major | F # maj7 | F # -7 | A # -7 | Bmaj7 | C # 7 | D # -7 | F # -7 (b5) |

| F major | Fmaj7 | G-7 | A-7 | Bbmaj7 | C7 | D-7 | E-7 (b5) |

| Bb major | Bbmaj7 | C-7 | D-7 | Ebmaj7 | F7 | G-7 | A-7 (b5) |

| Eb major | Ebmaj7 | F-7 | G-7 | Abmaj7 | Bb7 | C-7 | D-7 (b5) |

| From major | Abmaj7 | Bb-7 | C-7 | Dbmaj7 | Eb7 | F-7 | F-7 (b5) |

| Db major | Dbmaj7 | Eb-7 | F-7 | Gbmaj7 | From 7 | Bb-7 | C-7 (b5) |

Table of the scales for all major keys

The same system is used to assign the scales for the levels of the natural minor scales, with level I-7 being equated with level VI-7 in major.

Basic qualities of the scale tones

In summary, the AST assigns the tones of a chord scale to the following three groups

- Chord tones: Tones of the seventh chord, which represents the harmony as a basic chord.

- Tensions: Tones added to the basic chord that create special tensions and colors.

- Avoid tones: Tones that sound strongly dissonant in a chord.

Using the chord scales

The AST provides a system in which music can be thought. Music is made the way people think.

The fact that in the above example the seven scales only contain notes of the C major scale should not hide the fact that each of these scales has its own timbre. This is quickly apparent when you consider that major and minor are also scales (Ionic and Aeolian). The relationship between their individual tones and their fundamental tone is decisive for the sound of the scales. The scales are sonically independent and should not be equated with a level or function. Mixolydian can also exist without the dominant function in major, e.g. B. in the blues as a tonic at the first level.

If the musician stays closer to the harmonic with a vertical view and emphasizes the basic chords and regards the tension tones as passing tones, this leads to the fact that chord tones are used more for melodic lines. The music seems more "good". If, on the other hand, he regards the chord tones and the tensions of the scales as equal in the horizontal perspective, fluid melodic lines are promoted. The result is "cooler" for many musicians. If the musician moves too much in the horizontal view of the scales without taking into account the vertical structures, the impression of the "scale doodle" easily arises. If the focus is also placed on the tension, which is what modern jazz likes to do, there is a risk that the listener will lose touch with the basic sound entirely.

The AST describes the possible tone supply of a chord progression. Now it is not only a question of the tone supply, but also the distribution of roles of the individual tones within the tone supply. If one thinks of chord progressions as horizontally lined up scales, every scale note has a basic quality. As a chord tone it can emphasize the harmony or as a tension it can provide even more tension. One and the same note can play a different role in a chord change. The distribution of roles of the individual tones or the focus of the roles within a piece has a decisive influence on the overall impression created by the music.

The AST describes in great detail the tonal potential that lies in chord progressions or cadences. Ultimately, the AST provides a basis for improvising, arranging and composing. Chord progressions in lead sheets, so-called changes, can be quickly designed with additional tones on this basis. The AST system has developed into a global standard. It is used among musicians for quick coordination and understanding of musical situations.

Further material

The AST is used to describe how music works. In addition to a comprehensive literature, there are tools that support the application of the AST. A number of websites provide the possible scales for each chord or the possible scales and chords for each sequence of tones. The spectrum ranges from guitar fingering charts for chords and scales to software in which music is played with chord scales.

See also

literature

- Richard Graf, Barrie Nettles : The Chord Scale Theory & Jazz Harmonics. Advance Music, Mainz 1997, ISBN 978-3-89221-055-9 , 979-0-2063-0298-5.

- Frank Haunschild : The new theory of harmony. A musical workbook for classical, rock, pop and jazz. Volume 1. Extended and revised edition. AMA-Verlag, Brühl 1997, ISBN 3-927190-00-4 .

- Frank Sikora : New Jazz Harmony. Understand - hear - play. From theory to improvisation 8th edition. Schott Music, Mainz 2012, ISBN 978-3-7957-5124-1 (with 2 CDs).

Individual evidence

- ^ Frank Sikora: New Jazz Harmonielehre. Understand - hear - play. From theory to improvisation 8th edition. Schott Music, Mainz 2012, ISBN 978-3-7957-5124-1 , page 89

- ^ Richard Graf, Barrie Nettles: The chord scale theory & jazz harmonics. Advance Music, Mainz 1997, ISBN 978-3-89221-055-9 , 979-0-2063-0298-5, page 17

- ^ Frank Sikora: New Jazz Harmonielehre. Understand - hear - play. From theory to improvisation 8th edition. Schott Music, Mainz 2012, ISBN 978-3-7957-5124-1 , page 93

- ^ Frank Sikora: New Jazz Harmonielehre. Understand - hear - play. From theory to improvisation 8th edition. Schott Music, Mainz 2012, ISBN 978-3-7957-5124-1 , page 90