To autumn

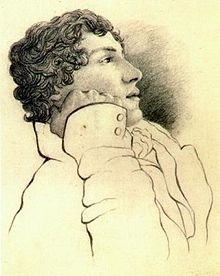

"To Autumn" is a poem by the English Romantic poet John Keats (October 31, 1795 - February 23, 1821). It was completed on September 19, 1819 and published in 1820 in a volume of poetry together with "Lamia" and "The Eve of St. Agnes". "To Autumn" is the last of a series of poems known as "Keats' Odes of 1819". Although he had little time to devote himself to poetry due to personal difficulties in 1819, he wrote the poem "To the Fall" after a walk on an autumn evening near Winchester . This work marks the end of his development as a poet, as he had to take up a job due to lack of money that no longer allowed him the lifestyle of a freelance poet. A little over a year after the poem was published, Keats died in Rome .

The poem consists of three eleven-line stanzas that depict the development of nature, especially the flora, over the course of the season. This development begins with the late ripening of the crops until harvest and ends with the last days of autumn, when winter is already tangible. The imagery is varied and vivid due to the personification of autumn and the description of its rich gifts and sensual impressions. Parallels to the English landscape painting of the time are clearly recognizable, Keats himself also describes that the effect of the stubble fields of his migration is similar to that of depictions in paintings. The work was interpreted as a commemoration of death, as a meditation and as an allegory of the poetic act of creation, moreover as Keats' answer to the Peterloo massacre , which occurred in the same year; not least as an expression of national feeling . As one of the most common poems in poetry collections, it has often been considered by literary critics to be one of the most perfect short poems in the English language.

background

In the spring of 1819 Keats wrote many of his great odes: "Ode on a Grecian Urn", "Ode on Indolence", "Ode on Melancholy", "Ode to a Nightingale" and "Ode to Psyche". From the beginning of June he devoted himself to other lyrical forms, including the tragedy "Otho the Great". Here he worked with his friend and roommate Charles Brown. He also unveiled the second half of "Lamia" completed and returned to his unfinished epic Hyperio n back. By autumn he was completely focused on a career as a poet, alternating between longer and shorter poems and pursuing the goal he had set himself to write more than 50 lines of verse a day. In the free time he read a wide variety of works, from Robert Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy to Thomas Chatterton's poems, to the essays by Leigh Hunt .

Despite his productivity as a poet, Keats suffered financial difficulties throughout 1819, including those of his brother George, who had emigrated to America and had been in financial difficulties ever since. However, these adversities gave him the time to write down his autumn poem on September 19th. It marks the last moment of his poetic career. Since he could no longer afford to devote his time to writing poetry, he worked on more profitable endeavors. His deteriorating health and personal stresses were further obstacles to the continuation of his poetic endeavors.

On September 19, 1819, Keats migrated along the River Itchen near Winchester. In a letter to his friend John Hamilton Reynolds on September 21, Keats describes the impression the landscape had made on him and its influence on the design of the autumn poem: “How beautiful the season is now - how fine the air is. There is a softened sharpness in it [...] I never liked stubble fields like I do now [...] Somehow a stubble field looks warm - like pictures look warm - this impressed me so much on my Sunday walk that I put it into poetic words [...]. “Not everything in his mind was pleasant at the time; the poet was already aware in September that he had to give up work on the "Hyperion" for good. Also in a note to the letter to Reynolds, Keats notes that he has given up this long poem. He did not send Reynolds the fall poem, but sent it with a letter of the same date to Richard Woodhouse, his publisher and friend.

After a revision, the poem went into the collection of poems of 1820, which Keats published under the title Lamia, Isabella, the Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems . The publishers feared negative reviews similar to those that had accompanied the 1818 edition of Endymion . However, they agreed to the publication provided that any potentially controversial poem would be removed beforehand. One wanted to avoid politically motivated criticism in order not to endanger the reputation of the book of poems.

The text

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss'd cottage-trees,

and fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For Summer has o'er-brimm'd their clammy cells.

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap'd furrow sound asleep,

Drows'd with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cider press, with a patient look,

you watch the last oozings hours by hours.

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too, -

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

Translation:

You time of the fog and the ripe fertility,

The late sun like a friend of the heart, Who, in

the course of time, conspired to bless all the vines,

which entwine around the thatched roof, and to fill them with fruit.

To load the trees, covered with moss, with apples

And to ripen all the fruit to the core;

To swell the pumpkin, and

to drive the sweet hazel nuts into their plump shawls ; to set the late splendor of

the blossoms for the bees, who

believe that the sunny days never end,

as long as summer fills their honeycombs to the brim.

Who hasn't seen you often in your attic?

Whoever looked outside would sometimes find you

sitting there carefree on the floor of the grain store,

your hair lifted up in the gentle wind;

Or in deep sleep on the harvested furrow, numbed

by the breath of poppy seeds, meanwhile your hook

protects the next swath with the entwined flowers;

Sometimes, like the quiet

grain picker, you cross the brook with your heavily laden head,

And at the apple press, with a calm look,

you watch the last hours quietly drain away .

Where are the songs of spring? Yeah where are you

Do not think about them, you have yours too -

clouds like feathers gently let the dead day bloom

And when touched all the stubble fields seem rose-colored;

Then the chorus of mosquitos resounds in mourning

over the river, lifted up and carried away in the pastures.

Of a light wind that always swells and dies;

And big lambs bleat loudly from the brook on the slope;

Crickets singing; and now with a soft whistle

a robin sounds from the garden fence;

And the swallows chirp happily in the heavens.

Subject

“To Autumn” describes in three stanzas three different aspects of autumn, its fertility, its abundance of labor and its eventual decline. In the course of the stanzas there is a development from early autumn to mid-autumn and from there to the announcement of winter. In accordance with this, the poem describes the course of a day from morning to noon and dusk. This development also corresponds to a change in sensory perception from the sense of touch to seeing and hearing. This triple symmetry can only be found in this ode.

In the course of the poem, autumn is metaphorically represented as a conspirator who lets the fruits ripen, who harvests and makes music. In the first stanza, the personified autumn promotes natural processes, maturation and growth, which have opposing effects in nature, but together give the impression that autumn will not end. In this stanza the fruits are still ripening and the flowers are still opening in warm weather. Stuart Sperry sees here an emphasis on the sense of touch, which is indicated by the imagery of growth and gentle movement, the swelling of the fruit and the bending of the branches like the abundance of hazelnuts.

In the second stanza, autumn is personified as a harvester , who is experienced by the viewer in various disguises and roles and who does work that is essential for the supply of the coming year. A certain course of action is missing, all movements are gentle. Autumn is not really represented in harvest work, it is sitting, resting or watching. On lines 14-15 he is depicted as an exhausted farm laborer. Towards the end, in lines 19-20, the steadiness of the gleaner again highlights the immobility in the poem. The advancing day is reflected in events that all suggest the drowsiness of the afternoon: the harvested grain is thrown, the harvester has fallen asleep or is returning home, the last drops of apple juice trickle from the press.

The last stanza contrasts the sounds of autumn with those of spring. It's not just those of autumn, but those of the evening. Mosquitoes complain and lambs bleat in the twilight. With the arrival of night within the final moments of the song, death slowly approaches on the verge of the end of the year. The adult lambs, like grapes and hazelnuts, are "harvested". The chirping swallows gather for take-off, leaving the fields empty. The chirping robin and the chirping cricket create the typical winter noises. The allusions to spring with the growing lambs and the wandering swallows remind the reader of the annual cycle of the seasons. The horizon opens up here in the last stanza from the individual season to life in general.

Of all his poems, “To Autumn” with its many concrete images is the closest to a representation of an earthly paradise. Keats also associates archetypal symbols with this time of year: autumn represents growth, maturity and finally the approaching death. Ideal and reality combine to form a unity in which the ideal finds fulfillment in life.

Literary scholars have pointed to a number of literary influences, including Virgil's Georgica , Edmund Spenser's Mutability Cantos , the language of Thomas Chatterton, Samuel Taylor Coleridge's Frost at Midnight , and an autumn essay by Leigh Hunt that Keats had read earlier.

"To Autumn" is thematically linked to other odes that Keats wrote in 1819. In his "Ode to Melancholy" the acceptance of the life process is an essential theme. In the autumn poem, however, this theme appears with a difference. The figure of the poet disappears here, there is no form of address or invitation from an imaginary reader. There are no open conflicts, and “dramatic debates, protests and evaluations are missing”. In the process of development there is a harmony between the finality of death and the indications of a renewal of life in the cycle of the seasons, in accordance with the renewal of a single day.

Reviewers have typically highlighted various aspects of the development process. Some emphasized renewal: Walter Jackson Bate points out that every stanza includes opposing ideas, here, for example, the idea of death, which, albeit indirectly, refers to the renewal of life. Bate and Jennifer Wagner show that the structure of the verse increases the expectation of what is to come. The couplet before the end of each stanza creates tension and emphasizes the main idea of continuity.

Harold Bloom, on the other hand, emphasized the "exhausted landscape", the completion, the aim of death, although "winter comes here like a person who hopes to die, with a natural sweetness". If death in itself is final, it comes here with a lightness and softness that can also be understood as an indication of an “acceptance of the process beyond the possibility of worry”. Growth is no longer necessary, maturation is complete, life and death are in harmony. Describing the cycle helps the reader feel part of "something greater than self," as James O'Rourke puts it, but the cycle of seasons comes to an end every year, analogous to the end of life. O'Rourke suggests that a kind of fear of the end is subtly implied at the end of the poem, although, unlike in the other great odes, the person of the poet is completely suspended. So there is at best a faint hint of fear that Keats may have felt himself.

Helen Vendler sees “To Autumn” as an allegory of poetic creation. Just as the farmer processes the fruits of the field into food, so the artist transforms the experience of life into a symbolic order that can preserve and promote the human spirit. This process involves an element of self-sacrifice on the part of the artist, analogous to the sacrifice of the grain that is used for human nutrition. The autumn poem transforms all of the world's senses into its rhythm and music.

In a 1979 essay, Jerome McGann argued that the fall poem was indirectly influenced by historical events, but that Keats had deliberately ignored the political landscape of the day. In contrast, Andrew Bennett, Nicholas Roe, and others worked out what they believed to be political allusions to the poem. Roe was of the opinion that there was a direct connection to the Peterloo massacre of 1819. Paul Fry later pointed out to McBann that Keats' poem in no way avoids the subject of social violence, since it explicitly deals with the encounter with death. But it is not a "politically coded escape from history". McGann, on the other hand, intended to protect Keats against allegations of political naivete by claiming that he was an intimidated and silent radical.

In 1999 Alan Bewell interpreted the landscape as an allegory of the English biomedical climate, which he saw endangered primarily by the influences of the colonies. Keats, who was medically educated, suffered from chronic illnesses himself and knew the "colonial discourse", was very aware of this.

In Bewell's opinion, the landscape of the autumn poem represents a healthy alternative to the pathological climate. Despite the "damp and cold" aspect of the fever, the over-maturity associated with the tropics, these elements, which are no longer as prominent as in the earlier poems, offset by the dry air of rural England. In his portrayal of elements of the peculiar English landscape in his environment, Keats was influenced by the contemporary poet and essayist Leigh Hunt , who shortly before came of the arrival of autumn with its migration of birds, especially the swallows, the end of harvest and manufacture of apple cider, as well as English landscape painting and the “pure” English idioms of Thomas Chatterton's poetry. Bewell is of the opinion that on the one hand Keats shows "a very personal expression of a desire for health", on the other hand he creates the "myth of a national environment". This “political” element of the poem was already assumed by Geoffrey Hartman , according to Bewell's account . He saw in Keats' autumn poem "an ideological poem whose form expresses a national idea".

Thomas McFarland urged caution in 2000. One should not overemphasize the “political, social or historical reading”, which distracts from the “perfect surface and blossom”. The most important things are the concentrated imagery and the allusive invocation of nature. They conveyed the "mutual interpenetration of vitality and mortality in the very nature of autumn".

construction

It is a poem with three stanzas, each of which has 11 lines. As with the other poems that were written in 1819, the establishment of a corresponding Ode of verse , Antistrophe and Epode . They have one line more than the other odes and put a two-line in front of the end line .

Keats had perfected the poetic techniques beforehand, but he deviates from the previous one, for example when he leaves out the narrator and uses more concrete ideas. There are also none of the usual dramatic developments and movements. The topic does not develop in leaps and bounds, but rather slowly progresses among the objects that remain the same. Walter Jackson Bate described this as "the union of progression and persistence", "energy at rest" - an effect that Keats himself called "stationing". At the beginning of the third stanza he uses the dramatic ubi sunt , a stylistic device that is associated with melancholy, and asks the personified subject: "Where are the spring songs?"

The iambic pentameter determines the form here, though greatly modified from the start pretty. Keats varies this form with the help of the Augustean inversion, with a stressed syllable at the beginning of the verse: "Time of mists and gentle fertility"; he also uses Spondeen with two emphatic accentuations at the beginning of the line: “Who hath not seen thee…”, “Where are the songs…?”

The rhyme scheme follows the ABAB pattern of the Sonnet, which is initially followed by CDEDCCE and CDECDDE in the further stanzas, i.e. contains a couplet in the two penultimate lines of verse. The linguistic means are often reminiscent of Endymion , Sleep and Poetry and Calidore . Keats characteristically uses monosyllabic words, for example in “… how to load and bless with fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run.” The words are emphasized by bilabial consonants (b, m, p), such as in the line “… for Summer has o'er-brimm'd their clammy cells. ”Long vowels are also deliberately used to give the poem an appropriate slow pace:“… while barred clouds bloom the soft dying day ”.

Before publication, Keats revised the language of the poem. He changed "Drows'd with red poppies" to "Drows'd with the fume of poppies" to emphasize the smell more than the color. “While a gold cloud” becomes “While barred clouds”, an attributive participle is inserted, which gives the clouds a more passive character. “Whoever seeks for thee may find” is replaced by “whoever seeks abroad may find”. Many of the lines in the second stanza were rewritten from scratch, primarily those that did not fit into a rhyme scheme. Minor changes affect the additional punctuation marks and capitalization.

reception

In mutual praise, literary critics like literary scholars have declared To Autumn one of the best poems in English. AC Swinburne presented it with the Ode on a Grecian Urn as "the closest to perfection" of all Keats 'odes. Aileen Ward called it "Keats' most perfect and least burdened poem"; Douglas Bush stated that the poem was "flawless in structure, texture, tone and rhythm"; Walter Evert wrote in 1965 that “To Autumn” was “the only perfect poem Keats ever wrote - and if this seems to detract from his extraordinary enrichment of the English tradition of poetry, I would like to quickly add that I am interested in the absolute perfection of entire poems think in which every part is indispensable and in the effect consistent with every other part of the poem. "

Early reviews saw the poem as part of Lamia, Isabella, the Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems . In July 1820, in the Monthly Review, an anonymous critic claimed , “this writer is very rich both in imagination and fancy; and even a superabundance of the latter faculty is displayed in his lines 'On Autumn', which brings the reality of nature more before our eyes than almost any description that we remember. [...] If we did not fear that, young as is Mr K., his peculiarities are fixed beyond all the power of criticism to remove, we would exhort him to become somewhat less strikingly original, —to be less fund of the folly of too new or too old phrases, —and to believe that poetry does not consist in either the one or the other. " Josiah Conder mentioned in the September 1820 Eclectic Review “One naturally turns first to the shorter pieces, in order to taste the flavor of the poetry. The following ode to Autumn is no unfavorable specimen. " In Edinburgh Magazine for October 1820, the autumn poem was awarded "great merits" along with The ode to 'Fancy' .

The Victorian era was marked by a disparaging judgment of Keat's weak character; his poems showed sensuality without substance, but slowly gained tentative recognition towards the middle of the century. In 1844, George Gilfillian rated the autumn poem as one of the finest of Keat's shorter poems. In 1851 David Macbeth Moir praised the four Odes - To a Nightingale, To a Grecian Urn, To Melancholy, and To Autumn, for their content of deep thought and their picturesque and suggestive style. In 1865, Matthew Arnold emphasized that the poem was indescribably delicate, magical and perfect. In 1883, John Dennis called the poem one of the most precious gems in poetry. In 1888 the Encyclopedia Britannica stated that the autumn poem was perhaps the closest to absolute perfection with the ode to a Greek urn.

In 1904 Stephen Gwynn claimed, "above and before all [of Keats's poems are] the three odes," To a Nightingale, "On a Grecian Urn," and "To Autumn". Among these odes criticism can hardly choose; in each of them the whole magic of poetry seems to be contained. " Sidney Colvin pointed out in 1917, “the ode“ To Autumn ”[…] opens up no such far-reaching avenues to the mind and soul of the reader as the odes“ To a Grecian Urn ”,“ To a Nightingale ”, or "On Melancholy", but in execution is more complete and faultless than any of them. " In 1934 Margaret Sherwood stated that the poem was "a perfect expression of the phase of primitive feeling and dim thought in regard to earth processes when these are passing into a thought of personality."

Harold Bloom called “To Autumn” in 1961 the “most perfect shorter poem in the English language”. Walter Jackson Bate agreed with this judgment in 1963: "[...] each generation has found it one of the most nearly perfect poems in English." In 1973 Stuart Sperry wrote, “'To Autumn' succeeds through its acceptance of an order innate in our experience - the natural rhythm of the seasons. It is a poem that, without ever stating it, inevitably suggests the truth of 'ripeness is all' by developing, with a richness of profundity of implication, the simple perception that ripeness is fall. " 1981, William Walsh took the view, “Among the major Odes [...] no one has questioned the place and supremacy of 'To Autumn', in which we see wholly realized, powerfully embodied in art, the complete maturity so earnestly labored at in Keats's life, so persuasively argued about in his letters. " Helen Vendler stated in 1988, "in the ode 'To Autumn,' Keats finds his most comprehensive and adequate symbol for the social value of art."

Translations into German (selection)

- Mirko Bonné : To autumn. At Lyrikwelt .

- The autumn time. In: John Keats: Gedichte (= print of the Ernst Ludwig press. 9). Transferred by Gisela Etzel . Insel-Verlag, Leipzig 1910, pp. 23-24, (from Zeno).

- Christiane Wyrwa: John Keats. (1795-1821). Approaches to life and work (= Punctum. Treatises from Art & Culture. 6). Scaneg, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-89235-106-6 , p. 199.

- Paul Hoffmann : To autumn , at Otago. German Studies , University of Otago

Web links

- Audio: Listen to Robert Pinsky read “To Autumn” by John Keats on poemsoutloud.net

literature

- Meyer H. Abrams : Keats's Poems: The Material Dimensions. In: Robert M. Ryan, Ronald A. Sharp (Eds.): The Persistence of Poetry. Bicentennial Essays on Keats. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst MA 1998, ISBN 1-55849-175-9 , pp. 36-53.

- Matthew Arnold : Lectures and Essays in Criticism (= The Complete Prose Work of Matthew Arnold. Volume 3). The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor MI 1962, OCLC 3012869 .

- Walter Jackson Bate: John Keats. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 1963, OCLC 291522 .

- Walter Jackson Bate: The Stylistic Development of Keats. Reprinted edition. Humanities Press, New York NY 1962, OCLC 276912 , (first published 1945).

- Thomas Baynes (Ed.): Encyclopædia Britannica. Volume 1. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1888, OCLC 1387837 .

- Andrew Bennett: Keats, Narrative and Audience. The Posthumous Life of Writing (= Cambridge Studies in Romanticism. 6). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1994, ISBN 0-521-44565-5 .

- Alan Bewell: Romanticism and Colonial Disease. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore MD et al. 1999, ISBN 0-8018-6225-6 .

- John Blades: John Keats. The poems. Palgrave, Basingstoke et al. 2002, ISBN 0-333-94895-5 .

- Harold Bloom : The Visionary Company. A Reading of English Romantic Poetry. Revised and enlarged edition, 5th printing. Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY et al. 1993, ISBN 0-8014-9117-7 (originally published 1961; revised edition 1971).

- Harold Bloom: The Ode "To Autumn". In: Jack Stillinger (Ed.): Keats's Odes. A Collection of Critical Essays. Prentice-Hall, Englewood NJ 1968, pp. 44-47, OCLC 176883021 .

- James Chandler: England in 1819. The Politics of Literary Culture and the Case of Romantic Historicism. University of Chicago Press, Chicago IL et al. 1998, ISBN 0-226-10108-8 .

- Sidney Colvin : John Keats. His Life and Poetry, his Friends, Critics and After-Fame. Macmillan, London 1917, OCLC 257603790 , (digitized)

- Timothy Corrigan: Keats, Hazlitt and Public Character. In: Allan C. Christensen, Lilla M. Crisafulli Jones, Giuseppe Galigani, Anthony L. Johnson (Eds.): The Challenge of Keats. Bicentenary Essays 1795-1995 (= DQR Studies in Literature. 28). Rodopi, Amsterdam et al. 2000, ISBN 90-420-0509-2 , pp. 145–158, (online)

- John Dennis: Heroes of Literature, English Poets. A Book for Young Readers. Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge et al., London et al. 1883, OCLC 4798560 , (digitized version )

- Walter H. Evert: Aesthetic and Myth in the Poetry of Keats. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1965, OCLC 291999 .

- William Flesch: The Facts on File Companion to British Poetry. 19th Century. Facts on File, New York NY 2010, ISBN 978-0-8160-5896-9 .

- Paul H. Fry: A Defense of Poetry. Reflections on the Occasion of Writing. Stanford University Press, Stanford CA 1995, ISBN 0-8047-2452-0 .

- Robert Gittings: John Keats. Heinemann, London 1968, OCLC 295596 .

- Stephen Gwynn: The Masters of English Literature. Macmillan, London 1904, OCLC 3175019 , (digitized)

- Geoffrey Hartman : Poem and Ideology: A Study of Keats's "To Autumn". (1975). In: Harold Bloom (Ed.): John Keats. Chelsea House, New York NY 1985, ISBN 0-87754-608-8 , pp. 87-104.

- Lord Houghton: The Life and Letters of John Keats. New edition. Moxon, London 1867, (digitized version)

- Geoffrey M. Matthews (Ed.): Keats. The Critical Heritage. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1971, ISBN 0-7100-7147-7 .

- Thomas McFarland: The Masks of Keats. The Endeavor of a Poet. Oxford University Press, Oxford et al. 2000, ISBN 0-19-818645-2 .

- Jerome McGann: Keats and the Historical Method in Literary Criticism. In: MLN. Volume 94, No. 5, 1979, ISSN 0026-7910 , pp. 988-1032, JSTOR 2906563 .

- Andrew Motion : Keats. University of Chicago Press, Chicago IL 1999, ISBN 0-226-54240-8 .

- James O'Rourke: Keats's Odes and Contemporary Criticism. University Press of Florida, Gainesville FL et al. 1998, ISBN 0-8130-1590-1 .

- Stanley Plumly: Posthumous Keats. A Personal Biography. WW Norton, New York NY et al. 2008, ISBN 978-0-393-06573-2 .

- Maurice R. Ridley: Keats' Craftsmanship. A Study in Poetic Development. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1933, OCLC 1842818 .

- Margaret Sherwood: Undercurrents of Influence in English Romantic Poetry. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA 1934, OCLC 2032945 .

- Stuart M. Sperry: Keats the Poet. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ 1973, ISBN 0-691-06220-X .

- John Strachan (Ed.): A Routledge Literary Sourcebook on the Poems of John Keats. Routledge, London et al. 2003, ISBN 0-415-23477-8 .

- Helen Vendler: The Music of What Happens. Poems, Poets, Critics. Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA et al. 1988, ISBN 0-674-59152-6 .

- Jennifer Ann Wagner: A Moment's Monument. Revisionary Poetics and the Nineteenth Century English Sonnet. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press et al., Madison NJ et al. 1996, ISBN 0-8386-3630-6 .

- William Walsh: Introduction to Keats. Methuen, London et al. 1981, ISBN 0-416-30490-7 .

- Interpretations

- Egon Werlich: John Keats, "To Autumn". In: Egon Werlich: Poetry Analysis. Great English Poems interpreted. With additional notes on the biographical, historical, and literary background. Lensing, Dortmund 1967, pp. 101-121.

- Ulrich Keller: The moment as a poetic form in the poetry of William Wordsworth and John Keats (= Frankfurt contributions to English and American studies. 4, ZDB -ID 121990-x ). Gehlen, Bad Homburg vdHua 1970, pp. 128-138, (at the same time: Frankfurt am Main, University, dissertation, 1967).

- Kurt Schlueter: The English Ode. Studies of their development under the influence of the ancient hymn. Bouvier, Bonn 1964, pp. 217-235.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Bewell: Romanticism and Colonial Disease. 1999, p. 176.

- ^ Bate: John Keats. 1963, p. 580.

- ↑ a b Bate: John Keats. 1963, pp. 526-562.

- ^ Gittings: John Keats. 1968, pp. 269-270.

- ^ Motion: Keats. 1999, p. 461.

- ^ Bate: John Keats. 1963, p. 580.

- ^ Houghton: The Life and Letters of John Keats. New edition. 1867, p. 266.

- ^ Bate: John Keats. 1963, p. 585.

- ^ Evert: Aesthetic and Myth in the Poetry of Keats. 1965, pp. 296-297.

- ^ McGann: Keats and the Historical Method in Literary Criticism. In: MLN. Volume 94, No. 5, 1979, pp. 988-1032, here pp. 988-989.

- ↑ a b c Sperry: Keats the Poet. 1973, p. 337.

- ↑ a b Bate: John Keats. 1963, p. 582.

- ↑ The personification in the full sense only becomes clear in the second stanza.

- ↑ a b Wagner: A Moment's Monument. 1996, pp. 110-111.

- ^ Bate: John Keats. 1963, pp. 582-583.

- ↑ Sperry: Keats the Poet. 1973, p. 341.

- ^ Bate: John Keats. 1963, pp. 581-583.

- ^ O'Rourke: Keats's Odes and Contemporary Criticism. 1998, p. 173.

- ^ Helen Vendler, discussed in O'Rourke: Keats's Odes and Contemporary Criticism. 1998, p. 165.

- ↑ Hartman: Poem and Ideology: A Study of Keats's "To Autumn". (1975). In: Bloom (Ed.): John Keats. Pp. 87-104, here p. 100; Bewell: Romanticism and Colonial Disease. 1999, pp. 182-183.

- ^ Harold Bloom: The Visionary Company. A Reading of English Romantic Poetry. Revised and enlarged edition. Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY et al. 1971, ISBN 0-8014-9117-7 , p. 434.

- ↑ a b c Bewell: Romanticism and Colonial Disease. 1999, p. 178.

- ^ Bate: The Stylistic Development of Keats. Reprinted edition. 1962, p. 522.

- ↑ a b c Bate: John Keats. 1963, p. 581.

- ↑ a b Bate: John Keats. 1963, p. 583.

- ^ Harold Bloom: The Visionary Company. A Reading of English Romantic Poetry. Revised and enlarged edition. Cornell University Press, Ithaca NY et al. 1971, ISBN 0-8014-9117-7 , p. 435.

- ^ O'Rourke: Keats's Odes and Contemporary Criticism. 1998, p. 177.

- ^ Vendler: The Music of What Happens. 1988, pp. 124-125.

- ^ McGann: Keats and the Historical Method in Literary Criticism. In: MLN. Volume 94, No. 5, 1979, pp. 988-1032.

- ↑ Strachan (Ed.): A Routledge Literary Sourcebook on the Poems of John Keats. 2003, p. 175.

- ^ Fry: A Defense of Poetry. 1995, pp. 123-124.

- ↑ Bewell: Romanticism and Colonial Disease. 1999, p. 177.

- ↑ Bewell: Romanticism and Colonial Disease. 1999, p. 162.

- ↑ Bewell: Romanticism and Colonial Disease. 1999, p. 163.

- ↑ Bewell: Romanticism and Colonial Disease. 1999, p. 231.

- ↑ a b Bewell: Romanticism and Colonial Disease. 1999, p. 182.

- ↑ Bewell: Romanticism and Colonial Disease. 1999, pp. 182-183.

- ↑ Bewell: Romanticism and Colonial Disease. 1999, p. 183.

- ↑ Hartman: Poem and Ideology: A Study of Keats's "To Autumn". (1975). In: Harold Bloom (Ed.): John Keats. 1985, pp. 87-104, here p. 88; quoted in Bewell: Romanticism and Colonial Disease. 1999, p. 176.

- ^ McFarland quotes Shelley.

- ^ McFarland: The Masks of Keats. 2000, pp. 223-224.

- ^ McFarland: The Masks of Keats. 2000, p. 221.

- ^ Bate: John Keats. 1963, p. 499.

- ^ A b c Bate: The Stylistic Development of Keats. Reprinted edition. 1962, pp. 182-184.

- ^ Bate: John Keats. 1963, pp. 581-582.

- ^ Bate: John Keats. 1963, pp. 581-584.

- ^ Flesch: The Facts on File Companion to British Poetry. 19th Century. 2010, p. 170.

- ^ Blades: John Keats. The poems. 2002, p. 104.

- ^ Ridley: Keats' Craftsmanship. A Study in Poetic Development. 1933, pp. 283-285.

- ^ Bate: The Stylistic Development of Keats. Reprinted edition. 1962, p. 183.

- ^ Ridley: Keats' Craftsmanship. A Study in Poetic Development. 1933, pp. 285-287.

- ^ Bennett: Keats, Narrative and Audience. 1994, p. 159.

- ^ Evert: Aesthetic and Myth in the Poetry of Keats. 1965, p. 298.

- ^ Matthews (Ed.): Keats. The Critical Heritage. 1971, p. 162.

- ^ Matthews (Ed.): Keats. The Critical Heritage. 1971, p. 233.

- ^ Matthews (Ed.): Keats. The Critical Heritage. 1971, p. 215.

- ^ Matthews (Ed.): Keats. The Critical Heritage. 1971, pp. 27, 33, 34.

- ^ Matthews (Ed.): Keats. The Critical Heritage. 1971, p. 306.

- ^ Matthews (Ed.): Keats. The Critical Heritage. 1971, pp. 351-352.

- ^ Arnold: Lectures and Essays in Criticism. 1962, pp. 376, 380.

- ↑ Dennis: Heroes of Literature, English Poets. A Book for Young Readers. 1883, p. 372.

- ↑ Baynes (Ed.): Encyclopædia Britannica. Volume 1. 1888, p. 23.

- ^ Gwynn: The Masters of English Literature. 1904, p. 378.

- ↑ Colvin: John Keats. 1917, pp. 421-422.

- ↑ Sherwood: Undercurrents of Influence in English Romantic Poetry. 1934, p. 263.

- ^ Bloom: The Visionary Company. Revised and enlarged edition, 5th printing. 1993, p. 432.

- ↑ Sperry: Keats the Poet. 1973, p. 336.

- ^ Walsh: Introduction to Keats. 1981, p. 118.

- ^ Vendler: The Music of What Happens. 1988, p. 124.