Bisclavret

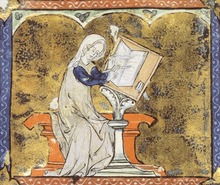

Bisclavret ("The Werewolf", modern French pronunciation: [ˌbisklaˈvrɛ] ) is the title of one of the twelve Lais of Marie de France and was written around 1170. The work, written in Anglo-Norman language , tells the story of a werewolf who was forced by the betrayal of his wife will remain in his animal form.

background

Marie de France claims in the introduction that she translated the story, like all of her lais, from Breton . At least the motifs of their stories actually come from the Breton or Celtic legends.

content

Bisclavret , a respected British nobleman, disappears for a full three days every week without anyone knowing where - not even his wife. Finally she asks him to tell her about his secret and he confesses to her that he is a werewolf. After some initial reluctance, he also tells her where he keeps his clothes hidden so that he can turn back into a human after his animal episodes. Bisclavret's wife is so shocked by the news that she no longer wants to "share the bed with him" and she ponders how to get away from her husband. She turns to a knight who has loved her for a long time and tells him to steal her husband's clothes, whereupon Bisclavret can no longer transform himself into a person. After he does not return and the search for his followers is unsuccessful, his wife marries the knight.

The following year the wolf-shaped Bisclavret is surrounded by the king's hunting dogs during a hunt. As the wolf sees the king, the hunted one runs up to him to beg his mercy. This behavior amazes the king so much that he orders his people to call back the dogs. Everyone is impressed by the generosity and friendliness of the wolf and the king takes Bisclavret, still in wolf form, to his castle.

The knight, who has meanwhile married Bisclavret's wife, is invited to a solemn ceremony in the royal palace a little later along with many other nobles. When Bisclavret sees him, he attacks him. Since the wolf has never been violent before, it is assumed at court that the knight must have done him great injustice. Soon after, the king visits the noble's possessions and brings the wolf with him. Bisclavret's wife hears of the arrival of the king and brings him many presents. But when Bisclavret sees his former wife, he attacks her and bites off her nose.

A wise man explains that the wolf has never acted like this before and that the woman attacked is the woman of the knight whom Bisclavret had attacked before. In addition, this woman was previously the wife of the lost nobleman Bisclavret. The king questions Bisclavret's wife under torture, whereupon she finally confesses everything and surrenders the stolen clothes. The king's men take off their clothes in front of the wolf, but the wolf ignores them. The wise man then suggested that the wolf and his clothes should be taken to a bedchamber so that he could dress there. So Bisclavret is finally transforming back. He gets his possessions back while his wife and the knight are sent into exile by the king. Many of the female offspring of Bisclavret's wife are born without noses and all of her children are "easy to recognize by their faces and looks."

Word and name "Bisclavret"

In the introduction, Marie de France uses the old French word “garwalf” among other things in the variant “garwaf” , which originated from an opened old Franconian * wariwulf , and the Breton “bisclavret” synonymous with “werewolf”.

Bisclavret ad nun en bretan,

Garwaf l'apelent li Norman

His name is Bisclavret in Breton and the Normans call him Garwaf

She draws a clear dividing line between the protagonist Bisclavret and ordinary werewolves. Their violence is not his own.

Adaptations

The substance was also used in the stories Melion and Biclarel . The Strengleikar (" string instruments "), commissioned by King Håkon IV in the middle of the 13th century, contains Old Norse prose translations of the Lais by Marie de France, including Bisclavret . In 2011 Emilie Mercier also made a short film that tells this story in animated images based on motifs from church windows.

literature

Primary literature

Old French edition of works by Marie de France:

German edition of the Lais:

- Wilhelm Hertz, Günther Schweikle (ed. And epilogue): Marie de France. Poetic tales based on old Breton love sagas. Phaidon, Essen 1986, ISBN 3-88851-115-1 .

English version:

- Keith Busby (ed.), Glyn S. Burgess (translation): The Lais of Marie de France. Penguin Books, London 2011, ISBN 0-14-044759-8 .

Secondary literature

- Manfred Bambeck: The werewolf motif in "Bisclavret". in: Journal for Romance Philology. Number 89, 1973, pp. 123-47.

- Erich Köhler: Lectures on the history of French literature. P. 64 ff. Digital version (PDF; 1.2 MB)

- TM Chotzen: Bisclavret. in: Etudes Celtiques. Number 2, 1937, pp. 33-44.

- Jean Rychner: Les Lais du Marie de France. in: Les Classiques Français du Moyen Age. Number 93, Champion, Paris 1973.

- Judith Rice Rothschild: Narrative Technique in the Lais of Marie de France: Themes and Variations. Volume 1. UNC Department of Romance Languages, Chapel Hill 1974.

- HW Bailey: “Bisclavret” in Marie de France. Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies 1, 1981, pp. 95-97.

- William Sayers: Bisclavret in Marie de France: A Reply. in: Cambridge Medieval Celtic Studies. Number 4, 1982, pp. 77-82.

- Michelle A. Freeman: Dual Natures and Subverted Glosses: Marie de France's "Bisclavret". in: Romance Notes. Number 25, 1985, pp. 285-301.

- Edith Joyce Benkov: The Naked Beast: Clothing and Humanity in "Bisclavret". in: Chimères. 19.2, 1988, pp. 27-43.

- Matilde Tomaryn Bruckner: Of Men and Beasts in "Bisclavret". in: The Romanic Review. Number 82, 1991, pp. 251-69.

- Hans Schwerteck: A new etymology of "Bisclavret". in: Romance Research. Number 104.1-2, 1992, pp. 160-63.

- Jean Jorgensen: The Lycanthropy Metaphor in Marie de France's “Bisclavret”. in: Selecta: Journal of the Pacific Northwest Council on Foreign Languages. Number 15, 1994, pp. 24-30.

- Rhonda Knight: Werewolves, Monsters, and Miracles: Representings Colonial Fantasies in Gerald of Wales's Topographia Hibernica. in: Studies in Iconography. Number 22, 2001, pp. 55-86.

- Paul Creamer: Woman-Hating in Marie de France's "Bisclavret". in: The Romanic Review. Number 93, 2002, pp. 259-74.

- John Carey: Werewolves in Medieval Ireland. in: Cambrian Medieval Celtic Studies. Number 44, Winter 2002, pp. 37-72.

- David Alfred and James Simpson: The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Volume A. WW Norton, New York 2006 ISBN 1-59871-361-2 .

- Leslie A. Sconduto: Metamorphoses of the Werewolf: A Literary Study from Antiquity through the Renaissance. McFarland, Jefferson (NC) 2008, ISBN 0-7864-3559-3 .

- Joseph Black: Bisclavret. in: The Broadview Anthology of British Literature. 2nd edition, Volume 1. Broadview Press, Peterborough (Ont.) 2009, ISBN 1-55111-965-X . Pp. 181-188.

See also

Web links

- English edition of the story on clas.ufl.edu (PDF; 25 kB), translated by Judith P. Shoaf (1996)

- For filming of the material, see filmstarts.de

- Information on the filming of the legend on videos.arte.tv (German)

- Bisclavret in the Internet Movie Database (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ David Alfred and James Simpson: The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Volume A. WW Norton, New York 2006 ISBN 1-59871-361-2 .

- ↑ a b Joseph Black: Bisclavret. in: The Broadview Anthology of British Literature. 2nd edition, Volume 1. Broadview Press, Peterborough (Ont.) 2009, ISBN 1-55111-965-X .

- ↑ Algirdas Julien Greimas, Dictionnaire de l'Ancien Français , Larousse 2004

- ↑ a b Leslie A. Sconduto: Metamorphoses of the Werewolf: A Literary Study from Antiquity through the Renaissance. McFarland, Jefferson (NC) 2008, ISBN 0-7864-3559-3 .

- ↑ English texts (PDF; 669 kB) online

- ↑ Emilie Mercier on the making of the short film on videos.arte.tv