Chevrefoil

Chevrefoil , this is the Anglo- Norman title of the “ Lais vom Honeysuckle” (New French “Le lai du chèvrefeuille”).

This moving verse novella, which poetically depicts a short, secret encounter between Tristan and Isolde , the famous adulterous lovers, is attributed to the first known French-speaking poet, Marie de France . She is said to have created this song at the English royal court of Henry II and his wife, the patroness Eleanor of Aquitaine , in an old French dialect , the Anglo-Norman , before 1189. At the end of this Tristan novella, in verses 112/113, Marie de France claims that Tristan himself was the poet who composed this harp song, the "Lai of the Honeysuckle", in memory of the adventurous rendezvous :

V 112 Tristram, ki bien savait harper,

V 113 En avait fet un nuvel lai

V 112 Tristan, who could play the harp well

V 113 Has composed a new song from it

In the manuscript "H" Harley 978 from the late 13th century, which has passed down all twelve lais of Marie de France, this old French verse tale is found in eleventh place. With its 118 eight-syllable verses, it is the shortest of Marie's twelve verse novellas.

In “Chevrefoil” Marie stages an “aventure” made from the Irish-Breton Tristan fabric, from the legends of the Matière de Bretagne .

This “gioiello di poesia”, this “jewel of poetry” of the High Middle Ages , captivates with its strong expressiveness, in particular through the choice of a floral metaphor, which stands for indissoluble, lifelong love: twisting honeysuckle twigs wrap around a hazelnut stick . Because if you separate the hazel bush and the honeysuckle branches, which live in perfect symbiosis , both must die. Under the influence of the trobadoresque ideology of › fin'amor ‹ (old Occitan ), which radiated to the French-speaking English court , Marie de France, with her poetic imagination, transfers this floral metaphor to the fateful and fateful bond between the mythical lovers Tristan and Isolde :

V 08 De lur amur qui tant fu fine

V 09 Dunt il eurent meant dolur ,

V 10 Puis en mururent en un jur.

V 08 Of their love, which was so perfect,

V 09 And brought them so much suffering

V 10 That they died on the same day.

In this Lai, the hazel-honeysuckle symbol becomes a symbol of “perfect love” (V8 “ amur tant fine ”), which can only end in common death. Marie de France turns the hazelnut stick into the secret identification symbol of Tristan and Isolde. In doing so, the poet succeeds in giving the tragic fate of the inseparable couple an expressive magic in two verses that have become famous (V77 / 78). Marie de France achieves this fascinating effect through a formal poetic structure, through the stylistic device of chiasmus in verse 78:

V 77 'Bele amie, si est de nus:

V 78 Ne vus sanz mei, ne mei sanz vus! '

V 77 'Beautiful friend, that's how it is with us:

V 78 Neither you without me, nor I without you! '

content

King Marke of Cornwall banished his nephew Tristan from his kingdom because of his adulterous relationship with Queen Isolde. Longing for his lover, Tristan returns from exile at risk of life and limb. He hides in the woods, lives unrecognized with ordinary people and uses cunning to try to arrange secret meetings with Isolde. He learns that the queen will ride to Tintagel at Whitsun. He knows the forest path through which she will arrive well. Tristan puts the secret identification mark in her way there. To do this, he cut a hazel rod in the middle, made it square and engraved his name on it. This thing symbol had already led to secret meetings between the two of them earlier (V57 / 58):

V 61 Ceo fu la summe de l'escrit

V 62 Qu'il li aveit mandé e dit

…

V 68 D'euls deus fu il autresi

V 69 Cume del chevrefoil esteit

V 70 Ki a la codre se perneit:

V 71 Quant il s 'i est laciez e pris

V 72 E tut entur le fust s'est mis

V 73 Ensemble poënt bien durer

V 74 Mes ki puis les volt desevrer,

V 75 Li codres muert hastivement

V 76 E li chevrefoil ensement.

V 77 'Bele ami, si est de nus:

V 78 Ne vus sanz mei, ne mei sanz vus!'

V 61 That was the core of the message

V 62 That he had sent her

...

V 68 It was the same

with both of them V 69 As with the honeysuckle

V 70 That twines around the hazel

V 71 When it is tied to her

V 72 And has completely embraced the trunk,

V 73 So they can live together

V 74 But if you want to separate them,

V 75 So the hazel dies quickly

V 76 And so does the honeysuckle.

V 77 'Beautiful friend, that's how it is with us:

V 78 Neither you without me nor I without you!'

When Isolde saw the hazel stick, she recognized “all the letters on it” (v82 “tutes les letres i conut”) and understood the message immediately. Under the pretext of wanting to rest a little, she lets the entourage stop and, accompanied by her faithful servant Breguein, leaves the court company. There is a brief reunion with Tristan in the forest. They let their joy run wild. Isolde makes him a suggestion as to how he can reconcile himself with his uncle Marke, who still loves his nephew. Finally, the couple tearfully say goodbye.

Oil painting by Edmund Blair Leighton , 1901.

At the end of the poem, Marie de France claims that Tristan himself wrote the song about the honeysuckle:

V 111 Pur les paroles remembrer

V 112 Tristram, ki bien savait harper,

V 113 En avait fet un nuvel lai…

V 115 Gotelef l'apelent en engleis

V 116 Chevrefoil le nument Franceis

V 111 To keep the words in memory

V 112 Hat Tristan, who played the harp well

V 113 A new song was composed

V 115 Gotelef it is called in English

V 116 Chevrefoil the French call it.

Interpretations

Poetic structures

Romanists and Medievalists such as Jean-Charles Payen and Kurt Ringger emphasize that the Lais of Marie de France have lost none of their “ freshness and youthfulness ” even after eight centuries :

" Ce sont des œuvres belles, où les hommes de tous les temps se peuvent reconnaître. »(" These are beautiful works in which people of every era can recognize themselves. ")

Kurt Ringger wrote about himself in his book ›Die Lais. In relation to the structure of the poetic imagination, the task was to unravel the “ mysterious magic of this lais that still works ” by tracing it back to poetic structures in terms of content and form.

In Im Chevrefoil-Lai there is also the anticipation of the death of love (V7-10) as a poetic structure in terms of content :

V 07 De Tristram e de la reïne ,

V 08 De lur amur qui tant fu fine

V 09 Dunt il eurent meant dolur ,

V 10 Puis en mururent en un jur.

V 07 From Tristan and the Queen ,

V 08 From their love, which was so perfect,

V 09 And brought them so much suffering

V 10 That they died on the same day.

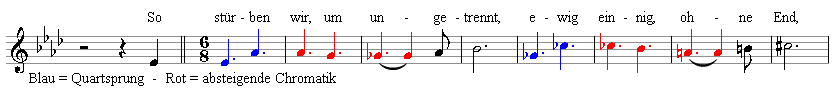

This love death motif forms a musical highlight in Richard Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde , 2nd act, 2nd act:

On a formal level, a chiastic crossing underlines the central message of the honeysuckle-hazel symbol, the inseparable love bond (V78): « Ne vus sanz mei, ne mei sanz vus! »(Neither you without me, nor I without you.)

Gottfried von Strasbourg uses the same formal stylistic device, the chiasmus , in his verse novel Tristan , written around 1250 :

V 129 a man a wîp, a wîp a man,

V 130 Tristan Isolt, Isolt Tristan.

In addition, one learns from Gottfried in verses 19.196–19.214 that Tristan invented songs and composed many beautiful melodies. Including "the wonderful Tristan Leich " (V19.201: "the noble Leich Tristanden"), "whom one loves and cherishes everywhere as long as this world exists." And Tristan always sang this refrain, in Old French dialect :

V 19.213 Îsôt ma drûe, Îsôt m'amie,

V 19.214 En vûs ma mort, en vus ma vie.

V 19.213 Isolde, my lover, Isolde, my friend

V 19.214 My death in you, my life in you!

In Marie's 12th Lai, Eliduc , there are similarly expressive verses:

V 671 Vus estes ma vie et ma mort,

V 672 En vus est tut mun confort!

V 671 You are my life and my death,

V 672 In you my consolation!

In the Explicit of the Song of the Honeysuckle (V 111-116) Marie de France succeeds in a very special poetological trick, namely a mise en abyme : the protagonist of the 'Chevrefoil', Tristan himself, was the author of this lais. Tristan wanted to write down this "eternal message" to Isolde so that the words would not be forgotten: "For Marie, poetry means remembering", "remembrance", Welt remembered.

Controversial discussions

In numerous specialist articles, philologists have argued over the question of what exactly Tristan had written on the hazel rod. Just his name? As it says in verses 53/54:

V 53 Quant il ad paré le baston,

V 54 De sun cutel escrit sun nun.

V 53 When he has scraped off the stick,

V 54 he writes his name on it with the knife.

Or was he carving a longer message on the stick? The chevrefoil text is ambiguous. He allows several readings. Because in verse 61 there is talk of the "core of the message" ("Ceo fu la summe de l'escrit") which Tristan Isolde sent. Had he sent her this message earlier in a letter ("lettre")? Or did he engrave them as letters ("lettres") on the stick, perhaps in a magical, Irish-Celtic Ogham script? In verses 80-82 it is said that when the queen saw the stick, “recognized all the letters on it” (“tutes les letres i connut”). Famous Romanists such as Pierre Le Gentil and Rita Lejeune argue that Tristan carved the full wording of the two "immortal verses" 77/78 into the stick:

V 77 'Bele amie, si est de nus:

V 78 Ne vus sanz mei, ne mei sanz vus!'

V 77 'Beautiful friend, that's how it is with us:

V 78 Neither you without me nor I without you!'

Leo Spitzer , on the other hand, thinks this is unlikely, because one could hardly perpetuate a longer text on a hazel rod. The stick itself is the message that is encoded in this thing symbol.

Connections to the Tristan fabric

Floral metaphors

Eilhart von Oberg's Middle High German verse novel Tristrant und Isalde (around 1170), the only completely preserved verse version of the Tristan legend, ends with a moving floral metaphor. A rose bush grows out of Isaldes grave , a vine sprouts out of Tristrant's body and both plants are inseparable. Tristrant (grapevine) and Isalde (rose bush) are forever united in death:

V 9709 and I was told asus

V 9710 of the king ainen rosenbusch

V 9711 let set uff that wib

V 9712 and ainen stock uff Tristandß lib

V 9713 from ainem winreben

V 9714 the growing show,

V 9715 that one with kainen things

V 9716 may bring from ai others.

In a version of the prose-tristan , an anonymous old French monumental novel, the traditions of which, in more than 80 manuscripts, fill 500 folio volumes, and which connects the Tristan material with the Lancelot-Graal cycle (Tristan becomes Arthurian knight ), one encounters one very much similar floral metaphor.

When King Marke learns about the magic of the love potion after the death of the protagonists and realizes that Isolde and Tristan did not act of their own free will, i.e. were innocent, he orders a solemn funeral. He has them buried in two graves on the left and right of a chapel:

«De dedens la tombe de Tristan yssoit une ronche belle et verte et foillue qui aloit par dessus la chapelle et descendoit le bout de la ronche sur la tombe d'Iseut et entroit dedens…. Le roy la fit par trois fois couper. A landemain restoit aussi belle et en autel estat comme elle avoit esté autrefois. »

“From the grave of Tristan a beautiful branch of thorns sprouted with green leaves. It grew over the chapel and lowered itself into Isolde's tomb ... The king had it cut three times. The next day it was in the same condition as before. "

In Joseph Bédier's opinion , both medieval authors probably had the same old French model, a lost, hypothetical Estoire de Tristan et Iseut , an archetypal Ur-Tristan . According to the French Germanist Danielle Buschinger, this presumed Ur-Tristan , the Estoire , can be reconstructed with the help of Eilhart's text.

Identification mark of the lovers

In the medieval text corpus of the Tristan saga, the reader learns how cunningly Tristan and Isolde proceed to secretly arrange rendezvous. As in the 'Chevrefoil' they make use of the agreed identification symbols:

V 6771 Trÿstrand do ain rÿß shot

V 6772 deer kúngin pfärd in the hands

- Tristan agrees with Isolde's loyal maid Brangäne to throw olive tree shavings, which he has marked with T and I , into the stream that crosses the women's quarters:

V 14.435 dar în sô throw a spân

…

V 14.441 when we see in then that

V 14.442 dâ bî we confess iesâ,

V 14.433 daz ir da bî the well sît.

- An anonymous Anglo-Norman poem, Le Donnei des Amants , also called Tristan Rossignol (Tristan Nightingale), tells how Tristan imitates bird calls, such as the nightingale strike, to inform Isolde of his presence. Li Donneis des amanz comprises 1,210 verses and was created in the last third of the 12th century at the court of Eleonores :

V 459 Entur la nuit, en un gardin

V 460 A la funtaine suz le pin,

V 461 Suz l'arbre Tristran seieit,

V 462 E aventures yi atendeit.

...

V 465 Il cuntrefit le russinol,

V 466 La papingai e l'oriol,

V 467 Et les oiseals de la gaudine

V 468 Ysoud escote la reïne

…

V 473 Mes par cel chant ben entendi

V 474 Ke près de luec ot sun ami

V 475 De grant engin esteit Tristans:

V 476 Apris l'aveit en tendres ang;

V 477 Chascun oisel sout contrefere

V 478 Ki en forest vent ou repeire

V 459 Towards night, in a garden

V 460 At the spring under a pine tree,

V 461 Tristan sat under the tree,

V 462 and waited there for Aventures .

...

V 465 He imitated the nightingale,

V 466 The parrot and the oriole ,

V 467 And the birds of the forest

V 468 Queen Isolde is listening

...

V 473 She recognizes by the song,

V 474 That her friend is very close

V 475 Tristran has a great talent:

V 476 He had already learned in a tender youth;

V 477 to imitate every bird

V 478 that flies or lives in the forest.

Tristan as a minstrel

In medieval texts, the literary figures Tristan and Isolde are presented as real historical figures, as individual poets. In various text passages and episodic poems from the Tristan, Grail and Arthurian material, Tristan appears personally as a harp or lyre-playing Ménestrel . He is quoted as a poet, composer and gifted instrumentalist who is credited with the authorship of lyric lais.

In Gottfried von Straßburg's verse novel Tristan (around 1210) it is said that Tristan invented songs and many beautiful melodies for all possible string instruments:

V 19.210 sô tihtete schanzûne,

V 19.211 rundate and Höfschiu liedelîn

V 19.210 he composed chansons,

V 19.211 rondeaus and courtly songs

He is especially the author of "the noble Leich Tristanden" (V 19.201), "whom one loves and cherishes everywhere so long as this world exists."

In the fourth continuation of the verse novel Perceval by Chrétien de Troyes , in the so-called Gerbert continuation, there is the long narrative poem "Tristan Ménestrel" , an insertion of 1,524 verses. It tells how King Marke organized a big tournament . Tristan senses an opportunity, unrecognized, to see Isolde again. He disguises himself as a minstrel. During his performance, he plays the secret melody of the lovers on a flute, the "Song of the Honeysuckle", which he once composed with Isolde:

V 758 [Tristrans] En sa main a pris un flagueil,

V 759 Molt dolcement en flajola,

V 761… le lai del Chievrefueil

V 758 [Tristan] has picked up a flute,

V 759 very gently he played

V 761 the song of the honeysuckle

Queen Isolde recognizes the melody immediately. In verse 777 she says: It is “the Lai whom he and I wrote and composed together” (V 777 “Le lai que moi et lui feïsmes”).

The old French prose Tristan is characterized by a peculiarity. Verse pieces are integrated into this prose story , several «lais lyriques bretons» , poems that deal with topics from the circle of the Matière de Bretagne and are partly attributed to Tristan. For example, he is the author of the famous Lai mortal . In this prose novel, Tristan appears as an unsurpassable harpist in music competitions. At the beginning of the section that tells how the jealous King Marke kills Tristan with a poisoned lance, it says:

«Or dist li contes que un jour estoit entrés mesire Tristan es cambres la roïne et harpoit un lay qu'il avoit fait. »

“Now the story goes that one day Messire Tristan came into the queen's room and played a Lai on the harp, which he had composed himself. "

In this prose novel, the poetic hero is made the greatest Lai composer and Lai poet of all time.

In a scene from the ancient Provencal verse “Flamenca” from the 13th century, minstrels give their best and perform new songs. A trobador sings the honeysuckle lai and accompanies himself on a lyre:

V 599 L'uns viola lais del Cabrefoil ,

V 600 E L'autre cel de Tintagoil;

V 599 One of them sang the honeysuckle Lai to the lyre,

V 600 And another recited the Lai of Tintagel ;

Source of Marie de France

Marie de France claims in the introductory verse that she got to know 'Chevrefoil' from oral and written tradition:

V 5 Plusurs le me unt cunté et dit

V 6 E jeo l'ai trové en escrit.

V 5 Many have told me about it.

V 6 And I found it written

For more than a hundred years, Romanists and Medievalists have been puzzling over whether Marie de France really knew an original version of the hypothetical "noble corpse Tristanden" that Gottfried raved about, or whether the alleged "original Chevrefoil" was just a matter of fact is a literary phantom, which in medieval texts repeatedly circulated as known, but whose literal content has nowhere been passed down. A Bernese song manuscript contains a «Lais dou Chievrefuel», which is attributed to Tristan. In the Excipit you can find out why the love poem has this title:

ke por ceu ke chievrefiaus

est plus dous et flaire miaus

ait nom cist douls lais

chievrefuels li gais.

Precisely because the honeysuckle is

lovelier and smells better

, the name of this gentle

honeysuckle is the beautiful honeysuckle

With the exception of the title, this layman of the Berner Liederhandschrift can in no way have been Marie's role model, because in terms of content it has nothing in common with Marie's ›Chevrefoil‹. There is no reference to the Tristan material or the imagery , the honeysuckle as a symbol of fatal, inseparable love.

Karl Warnke writes in the foreword to his edition of Lais de Marie de France in 1900:

“In my opinion, Marie heard a Breton Lai here, as everywhere, and put the story about this Lai in verse. In general, the existence of lais, who dealt with individual adventures of Tristan, can hardly be denied. In addition to our Lai (meaning ›Chevrefoil‹), we also know, directly or indirectly, three episodic poems about Tristan. ... What she borrowed from this and that source can no longer be said. "

The traditional lyrical Lais are mosaic stones, which treat smaller scenes from the large overall mosaic of Tristan, Grail and Arthurian material. The question of whether Marie de France had a third-party model for her Lai ›Chevrefoil‹ must remain open, because research has not found such an original text to date .

Marie's claims that she heard and found this honeysuckle Lai written (Incipit: Verse 5/6), and Tristan himself was his author (Excipit: Verse 112-113), is probably a narrative device of these first French-speaking people Poet, an author's fiction .

literature

Manuscripts

The "Honeysuckle-Lai" of Marie de France has come down to us in two manuscripts:

- Handwriting "H" : London, British Library , ms. Harley 978. This manuscript is fully digitized. The Chevrefoil-Lai is located on the British Library's server and includes the folia : f.150v , f.151 and f.151v . This manuscript is in the Anglo-Norman dialect of Old French. It was copied by a copyist in England in the mid-13th century. In Anglo-Norman , “honeysuckle” means chevrefoil .

- Handwriting "S" : Paris, BnF, ms. nouv. acq. fr. 1104. Online at: Gallica , Recueil de lais bretons. XIIIe siècle. In it: Le Lay du chievrefueil : f65 , f66 , f67 . This parchment dates from the second half of the 13th century and is written in the dialect of Paris, the old French dialect "Franzisch". In French dialect, "honeysuckle" means chievrefueil .

Editions

Faithfully following the handwriting “H”

- Alfred Ewert : Marie de France: Lais , Oxford 1944, New edition by Glyn Burgess, London 1995, Reprinted 2001 ISBN 1-85399-416-2 . This handwritten edition serves as the basis for all of the Chevrefoil quotes in this article.

- Jeanne Lods: Les Lais de Marie de France. Éditions Honoré Champion, Classiques français du Moyen Âge (CFM), Paris 1959.

- Philippe Walter: Marie de France: Lais. Bilingual edition (Old French / New French), Gallimard, Collection Folio, Paris, ISBN 978-2-07-040543-5 .

Reconstructed text based on the manuscripts "S" and "H"

- Karl Warnke (ed.): The Lais of Marie de France . With comparative comments by Reinhold Köhler. Second improved edition, Halle, Niemeyer ( Bibliotheca Normannica III), 1900. archive.org

- Karl Warnke (ed.): The Lais of Marie de France. Edited by Karl Warnke. With see note from Reinhold Köhler, along with Erg. v. Johannes Bolte. Third improved edition, publisher Niemeyer, Halle 1925.

Translations and revisions

- Philipp Jeserich: Marie de France: Lais. Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-019182-8 .

- Wilhelm Hertz : Poetic stories based on old Breton love sagas / Marie de France. Phaidon, Essen 1986, ISBN 3-88851-115-1 ( reworking in paired rhyming octosyllables ).

- Patricia Terry: The Honeysuckle and the Hazel Tree: Medieval Stories of Men and Women. University of California, 1995, ISBN 978-0-520-08379-0 : ( English Honeysuckle (Chevrefoil) ).

Bibliographies

- Bibliography on Marie de France in Arlima (Les Archives de littérature du Moyen Âge, French ).

- Glyn S. Burgess: An analytical bibliography - google books ( English ).

Secondary literature

- Joseph Bédier , Jessie L. Weston: Tristan ménestrel. Extrait de la continuation de Perceval, by Gerbert. In: Romania . 35, 1906 ( persee.fr ).

- Keith Busby: The Tristan Ménestrel of Gerbert de Montreuil and his position in the old French Arthurian tradition. In: Vox Romanica. 42, 1983, pp. 144-156. doi: 10.5169 / seals-32884 .

- Tatiana Fotitch, Ruth Steiner: Les lais du roman de Tristan en prose d'après le manuscrit de Vienne 2542. Critical edition. Munich Romanistic Works, Issue 38, Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich, 1974.

- Philippe Ménard: Les lais de Marie de France. Contes d'amour et d'aventures du Moyen Âge. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 3rd edition 1997, ISBN 2-13-047370-9 .

- Guy R. Mermier: En relisant le Chevrefoil de Marie de France. In: The French Review , vol. 48, N ° 5 (April, 1975), pp. 864-870, JSTOR 389335 .

- Kurt Ringger : The Lais. On the structure of the poetic imagination of Marie de France. Max Niemeyer Verlag Tübingen 1973, ISBN 3-484-52042-6 .

- Beate Schmolke-Hasselmann : Tristan as a poet: A contribution to the exploration of the lai lyrique breton. In: Romanesque research . 98th Volume, Issue 3/4, 1986, pp. 258-276, JSTOR 27939568 .

- Leo Spitzer : Marie de France - poet of problem fairy tales. In: Journal of Romance Philology, 50/1930, pp. 29–67 ( gallica.bnf.fr ).

- Leo Spitzer: La "lettre sur la baguette de coudrier" in le lai du Chevrefeuil. In: Romania, Volume 69, No. 273, 1946. pp. 80-90 ( persee.fr ).

- Henriette Walter : Honni soit qui mal y pense: L'incroyable histoire d'amour entre le français et l'anglais. Robert Laffont, Paris 2001, ISBN 2-253-15444-X .

Web links

- "Chevrefoil" ( Memento from January 28, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) - Alfred Ewerts edition true to the Anglo-Norman handwriting "H" Harley 978.

- German-language adaptation by Wilhelm Hertz in pairs of rhymed octosyllables - Project Gutenberg-DE .

- Sung recitation (old French) - on YouTube.

- Bibliographical entries in the RI-Opac of the Regesta Imperii : RI-Opac

Remarks

- ^ Eleanor of Aquitaine , Duchess of Aquitaine , Queen of France until 1152, Queen of England from 1154 through marriage to Henri II Plantagenêt , maintained a literary center in London, where she promoted French-speaking and Occitan poetry as a patron .

- ^ Death of Henry II as an ante quem terminus after: Philippe Ménard: Les lais de Marie de France. Contes d'amour et d'aventures du Moyen Âge. PUF , Paris 3rd edition 1997, ISBN 2-13-047370-9 , p. 19.

- ↑ With the conquest of England by the French Normans ( William the Conqueror , Battle of Hastings ) in 1066, the English royal court of Henry II and his wife, the patroness Eleanor of Aquitaine, as well as the English aristocratic circles, established the use of Norman , an old French dialect . The superstrate French influence in the variant Anglo-Norman , which developed there from the Norman, the vocabulary of the English language ( history of the English language ) about the mansions Plantagenet and Lancaster . Towards the end of the Hundred Years War , French was supplanted by Middle English (see: Henriette Walter: Honni soit qui mal y pense. P. 105).

- ^ British Library ms. Harley 978, Folia 150v, 151r, 151v: Folium 150v - At the bottom right of the manuscript the blue initial “A” marks the incipit of the Lais “Chevrefoil”: Vers 01 “ Asez me plest e bien le voil / Vers 02 Del lai qu ' hum nume Chevrefefoil ».

- ^ Karl Warnke (ed.): The Lais of Marie de France . With comparative comments by Reinhold Köhler. Second improved edition, Halle, Niemeyer (Bibliotheca Normannica III), 1900 ( archive.org ).

- ↑ The Romanist and Medievalist Cesare Segre called the Lais of Marie de France "un gioiello di poesia e un enigma di storia culturale": ( Italian ) Piramo e Tisbe nel Lai di Maria di Francia. In: Studi in onore di Vittorio Lugli e Diego Valeri. Venice 1961, Volume 2, p. 846.

- ^ Wilhelm IX. , Duke of Aquitaine , "The First Trobador", was the grandfather Eleanor of Aquitaine , the English Queen.

- ↑ Just like the Old French dialects, the Old Occitan dialects have a two- casus system with casus rectus and casus obliquus: "amors" is the case rectus for the subject position of the feminine noun in the sentence, while "amor", the casus obliquus of the word, is the same for all object positions is needed.

- ↑ Bartina Harmina Wind : L'idéologie courtoise dans les lais de Marie de France. In: Mélanges de linguistique romane et de philologie médiévale offerts à M. Maurice Delbouille , Gembloux (1964), Volume II, pp. 71 ff.

- ↑ a b c d Kurt Ringger : Die ›Lais‹. On the structure of the poetic imagination of Marie de France. Max Niemeyer Verlag Tübingen 1973, ISBN 3-484-52042-6 .

-

↑ a b c Verses from "Chevrefoil" are quoted here from the edition by Alfred Ewert : Marie de France: Lais , Oxford 1944, pp. 123–126, because this edition is as faithful as possible to the Anglo-Norman manuscript "H" ms . Harley holds 978, which is the only manuscript to contain all 12 lais.

All translations from Old French and Old Occitan into German are from the first author of this article. - ↑ "Honeysuckle" means "chevrefoil" in Anglo-Norman (see handwriting "H" Harley), in French "chievrefueil" (see handwriting "S"), in New French "chèvrefeuille", in Middle English "Gotelef", in modern English "(goat -leaf) honeysuckle ", in Altoczitan" Cabrefoil ".

- ^ Paisley Museum - WebSite of the Scottish Paisley Museum .

- ^ Jean-Charles Payen : Le motif du repentir dans la littérature française médiévale (des origines à 1230) . Genève, Librairie Droz, 1967. Publications romanes et françaises, XGVIII, p.330

- ↑ The Romanist Philipp Jeserich lists over 30 essays in his selected bibliography: Philipp Jeserich: Marie de France: Lais. Reclam-Verlag, 2015, ISBN 978-3-15-019182-8 , pp. 224-226.

- ^ Leo Spitzer: La "lettre sur la baguette de coudrier" dans le lai du Chevrefeuil. In: Romania. Volume 69 No. 273, 1946. pp. 80-90 ( persee.fr ).

- ^ Guy R. Mermier: En relisant le Chevrefoil de Marie de France. In: The French Review, vol. 48, N ° 5 (April, 1975), pp. 864-870, JSTOR 389335.

- ^ Anna Granville Hatcher: Le lai du Chievrefueil 61-78; 107-13. In: Romania. Volume 71, No. 283, 1950. pp. 330–344 ( persee.fr PDF), p. 330, on Persée (portal)

- ^ Pierre Le Gentil: On the subject of you lai du chèvrefeuille et de l'interprétation des textes médiévaux. In: Mélanges offerts à Henri Chamard. Paris 1951, p. 23.

- ^ Rita Lejeune: Le message d'amour de Tristan à Yseut. (Encore un retour au Lai du Chèvrefoil de Marie de France). In: Mélanges offerts à Monsieur Charles Foulon. Volume I, Rennes 1980, pp. 193/194.

- ^ Leo Spitzer: La "lettre sur la baguette de coudrier" dans le lai du Chevrefeuil. In: Romania. Volume 69, No. 273, 1946. pp. 80-90 ( persee.fr ), p. 81, on Persée (portal) .

- ↑ Danielle Buschinger (ed.): Eilhart von Oberg. Tristrant and Isalde (after the Heidelberg manuscript Cod. Pal. Germ 346) , Weideler Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-89693-409-0 , p. 314. The counting after Lichtenstein's output would be V9511 – V9518:

- ^ After the manuscript Paris, BnF ms. fr. 103

- ↑ Le roman de Tristan en prose . Published by Philippe Ménard, Verlag Droz Geneva, 1987–1997, nine volumes, approx. 2000 pages, ISBN 978-2-600-00190-8 (from final volume IX): Foreword to volume IX online at WorldCat

- ^ Joseph Bédier: La Mort de Tristan et Iseut, d'après le manuscrit fr. 103 de la Bibliothèque Nationale comparé au poème allemand d'Eilhart d'Olberg. In: Romania. Volume 15, 1866 ( gallica.bnf.fr ), pp. 481-510.

- ↑ Danielle Buschinger (ed.): Eilhart von Oberg. Tristrant and Isalde (based on the Heidelberg manuscript Cod. Pal. Germ 346) , Weideler Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-89693-409-0 , p. IX.

- ↑ Danielle Buschinger (ed.): Eilhart von Oberg. Tristrant and Isalde (after the Heidelberg manuscript Cod. Pal. Germ 346) , Weideler Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-89693-409-0 , p. 206. The counting after Lichtenstein's edition would be V 6541–6542

- ↑ Gottfried von Strasbourg: Tristan. Published by Rüdiger Krohn, Volume 2, Reclam-Verlag, 2014, ISBN 978-3-15-004472-8 , p. 270.

- ↑ afrz. Li Donneis des amanz , in German for example: The conversation of lovers , see Gaston Paris: p. 523 .

- ^ Gaston Paris : Le Donnei des Amants. In: Romania 25 (1896), p. 508 . On Gallica

- ↑ The manuscript is digitized online: Cologny (Switzerland), Fondation Martin Bodmer , Cod. Bodmer 82, f. 17r -24v ( Li Donnez des Amanz ) for 17r , on e-codices - Virtual Manuscript Library of Switzerland

- ↑ a b c d Beate Schmolke-Hasselmann : Tristan as a poet: A contribution to researching the lai lyrique breton. In: Romanesque research . 98th Volume, Issue 3/4, 1986, pp. 258-276, JSTOR 27939568 .

- ^ Gottfried von Strasbourg: Tristan - Internet Archive

- ↑ Keith Busby: The Tristan Ménestrel of Gerbert de Montreuil and his position in the old French Arthurian tradition. In: Vox Romanica. 42, 1983, pp. 144-156, doi: 10.5169 / seals-32883 .

- ^ Jeanne Lods: Les parties lyriques du Tristan en prose . In: Bulletin Bibliographique de la Société International Arthurienne. 7, 1955, pp. 73–78: Full text ( memento of the original dated August 4, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on BBSIA.

- ↑ Tatiana Fotitch, Ruth Steiner: Les lai du roman de Tristan en prose d'après le manuscrit de Vienne 2542. Critical Edition. In: Munich Romanistic Works. Issue 38, Wilhelm Fink Verlag, Munich, 1974.

- ^ Jean Maillard: Lais avec notation dans le Tristan en prose . In: Mélanges Riat Lejeune , Volume Two , Gembloux 1969, pp. 1347–1464.

- ^ Philippe Ménard (ed.), Laurence Harf-Lancner: Le roman de Tristan en prose. Volume IX, Verlag Droz, Geneva 1997, ISBN 2-600-00190-5 , p. 186.

- ^ Flamenca , Google books

- ↑ Wolfgang Golther : Tristan and Isolde in the poetry of the Middle Ages and the new time. Hirzel, Leipzig 1907, p. 235 ( archive.org )

- ^ Karl Bartsch: Chrestomathie de l'ancien français accompagnée d'une grammaire et d'in glossaire. Vogel, Leipzig 1884, pp. 227-230: ( archive.org ).

- ↑ Leo Spitzer: Marie de France - poet of problem fairy tales. In: Journal for Romance Philology. 50/1930, pp. 29-67 ( gallica.bnf.fr ), p. 43.