Flower wars

Flower wars ( Nahuatl Xochiyaoyotl ) were campaigns by the Aztecs and several peoples in their neighborhood, which did not serve the purpose of conquest, but solely to procure prisoners of war who were to be offered as human sacrifices to the gods in the Aztec cult of sacrifice.

Role of the Flower Wars in Aztec culture

There were two types of war for the Aztecs . One war was waged to subjugate neighboring peoples and to expand Aztec domination. The conquered peoples were then forced to pay tribute to the Aztecs. Since the Aztecs (in the narrower sense Tenochtitlaner and Tlatelolcoer on their island) could not cultivate enough despite extremely costly attempts to expand their arable land (Chinampas), they lived largely on the taxes of the subjugated peoples. The other war was fought for purely religious reasons and was called the Flower War. It was used to win living prisoners for the sacrificial ritual . These wars were triggered by a great famine. The Aztecs believed that through human sacrifice they could please the gods and end the famine. So that they could still wage flower wars in the distant future, the Aztecs deliberately gave smaller peoples a certain degree of independence, such as the Mixtecs or the Zapotecs in the south of their empire. The Aztecs fought flower wars with these and other neighbors, especially with the Tlaxcalteks living in the immediate vicinity of Tenochtitlan . According to reports based on pre-Hispanic traditions, repeated training of the warriors (in the sense of modern maneuvers) was an essential goal.

War preparation

At the beginning of the war of flowers, the news was publicly announced at all meeting places and places. When the troops were ready and the allied cities alerted and given their consent to take part in the war, the march began. Usually the priests marched ahead of the procession and carried the images of the gods. Some warriors from allied cities only joined the campaign on the way when the army marched past their cities. Well-developed roads made it possible to travel 20 to 30 kilometers a day. The size of the Aztec army changed constantly and was adapted to the needs. In the war against Coixtlahuacan z. B. the Aztec troop strength comprised 200,000 warriors and 100,000 porters. Other sources speak of a strength of up to 700,000 men.

Religion and rituals

When it was time to celebrate a religious festival, to bring in the harvest, or when new soldiers were to be recruited, the opposing parties broke off the war. Then they simply sent ambassadors to the neighboring peoples and all warring parties ceased fighting. The most important thing was to adapt the Flower Wars to the sacred calendar so that the wrath of the gods would not be aroused. For this the warring parties consulted their holy books.

Religion was the most important factor in the life of the Aztecs and their neighboring peoples. In their imagination, bloodthirsty gods ruled the universe and had to be constantly appeased by sacrifices so that they would not destroy the world. The people served the gods as a highly valued food.

Ritual cannibalism was widespread and the Aztecs, as well as other tribes such as the Totonaks and Tlaxkalteks, who were allied with the Spaniards early on, were very surprised when the Spaniards consumed human flesh or other foods sprinkled with human blood, which they used as a sign of reverence and despair Respect were offered, declined. They perceived this as an insult to their morality and religion, as well as an insult to their most important god, the god of war, Huitzilopochtli .

On the other hand, the fundamental rejection of cruel human sacrifice and cannibalism was well known even before the arrival of the Spaniards and Christianity, in the form of the comparatively benevolent god Quetzalcoatl (Feathered Serpent), who initially went west across the sea as the Toltecs' human ruler and whose return, together with the end of human sacrifices, was promised. For the Aztecs this was a second to third rank deity, but they were extremely religious to superstitious and very closely aware of all events. In the years immediately before the arrival of the Spaniards, a shrine was built to this god in Tenochtitlan, on Moctezuma II's orders. In addition, there was the fear of the Aztec ruling house of sitting on a presumptuous throne, namely that of the Toltecs, and of being pushed down by it again.

Course of the war of flowers

A flower war ran according to fixed rules and rituals , in stark contrast to the wars of conquest . The fighting usually started at daybreak with smoke signals . These signals were also used to coordinate attacks between different departments of the army. The signal to attack was also musical instruments such as drums and conch trumpets ( Tlapitzalli given). The opposing armies only sent one row of fighters against each other in the flower war. At the beginning of the fight, only the best warriors were allowed to fight. The others waited behind it until it was their turn. Young people were either not allowed to fight at all and had to be content with watching, or they were faced with an opponent of about the same age. During the fight, the opponents were cheered loudly by their comrades. When a warrior got tired, he would retreat and be replaced. This rotation allowed a fight for many hours. Even at the greatest risk to their own life, the Aztecs tried to catch the enemy alive. Because only those who took prisoners on the battlefield could rise in society. Prisoners brought fame and honor to the victor. The intervention of a third party in an ongoing duel for the benefit of a comrade was not permitted. When the fighters had taken enough prisoners, they left the battlefield and led the defeated opponents away. Since both the Aztecs and their opponents needed human sacrifices for their religious rites, the warring parties met regularly for these almost "sporting" battles.

Often there were wars of wear and tear with high losses. In 1504, the Tlaxcalteks defeated the Aztecs in a flower war that had unexpectedly turned into a real war.

Prisoners and victims

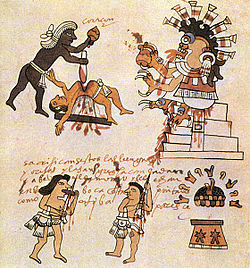

In the war of flowers, the enemy was only killed in combat if it could not be avoided; The aim was to capture warriors. When a man was trapped, a wooden collar was put on him, which not only prevented him from escaping, but also marked him as a prisoner. The man was then presented to the people in Tenochtitlán with this wooden collar . He was treated with honor and in most cases was sacrificed to the gods after a short time.

In a sacred ceremony, the priests cut out the heart of the doomed person alive and burned it in an " eagle bowl " (Cuauhxicalli). The corpses were pushed off the sacrificial pyramid. The warrior who made the prisoner and his family had the privilege of eating limb meat. This was not done, as is sometimes claimed, to cover an alleged protein deficit, but was a sacred ritual. The heads of the dead were neatly lined up on a frame made of wooden logs, the tzompantli . But when there was a big festival on the calendar or the dedication of a temple, the prisoners sometimes had to wait a long time to die. They were saved and collected for the holiday season. This gave the priests the opportunity to offer a greater number of human sacrifices to the gods . Before their sacrificial death, the prisoners often developed a warm relationship with the warrior who had defeated them on the battlefield. There was a custom that the loser called his conqueror "father".

literature

- Ross Hassig: Aztec Warfare. Imperial Expansion and Political Control . University of Oklahoma Press, Norman 1988, ISBN 0-8061-2121-1

- Matthew Restall: Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest . Oxford University Press, London 2003, ISBN 0-19-516077-0

See also

Web links

- Aztec Warriors: The Flower Wars. History on the Net

- Aztec Flower War. aztec-history.com (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Ursula Dyckerhoff : La Región del Alto Atoyac - la época prehispánica . In: Hanns J. Prem : Milpa y hacienda, tenencia de la tierra indígena y española en la Cuenca del Alto Atoyac, Puebla, México (1520–1650). Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden 1978. ISBN 3-515-02698-3 . Pp. 18-34.

- ^ Hanns J. Prem : Geschichte Altamerikas , Verlag Oldenbourg 2008, p. 46.

- ^ Hanns J. Prem: Die Azteken-Geschichte-Kultur-Religion , Verlag CH Beck, p. 93.

- ↑ Conrad Solloch: Performing Conquista , Publisher: Schmidt (Erich) S. 53rd

- ↑ Michael Harner: The ecological basis for Aztec sacrifice . In: American Ethnologist 4, 1977. pp. 117-135.

- ↑ Bernardino de Sahagun: From the world of the Aztecs , Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-458-16042-6 , p. 38.