Zultepec

Zultepec or Zultépec , later also called Tecoaque , was a city of the Acolhua in the Aztec Empire . The in the highlands of central Mexico preferred place is now an archaeological site located in the 2004 Tentative List of UNESCO - World Heritage Site was recorded.

In 1520, warriors from Texcoco captured numerous Spaniards and native allies in an act of revenge. The approximately 550 prisoners were then executed in Zultepec. After Hernán Cortés learned of the massacre, he sent a punitive expedition and had Zultepec destroyed in 1521.

Coordinates: 19 ° 35 ′ 6 ″ N , 98 ° 37 ′ 30 ″ W.

location

Zultepec is located approx. 1 km southwest of the present-day town of San Felipe Sultepec, which belongs to the municipality of Calpulalpan , or approx. 31 km northeast of Texcoco , near the former border between the former rulers of the Aztecs and the Tlaxcalteks who were enemies with them at an altitude of approx. 2630 m above sea level d. M.

history

Pre-Hispanic time

The origins of Zultepec go back to the 5th century AD; it was an important place on the important trade route from the central Mexican highlands to the Gulf of Mexico ; the 30 hectare city was built around 1200 AD. In its heyday it was inhabited by around 5,000 people who provided services for the traders, but also grew corn and beans and also produced pulque . In the pre-Hispanic times Zultepec belonged to the sphere of influence of Texcoco, the most important city in the Aztec Empire after Tenochtitlan .

Zultepec massacre

After Hernán Cortés had defeated the army of Pánfilo de Narváez in Cempoala in 1520, he not only took over the soldiers from Narváez, but also his entourage of auxiliaries and civilian companions, who acted as porters, cooks and traders. They were supposed to accompany him on his way back to Tenochtitlan and bring the goods captured by the victory to the capital. On the way, more and more locals who wanted to take part in a fight against the Aztecs joined the train, which slowed down more and more. Since Cortés wanted to get back to Tenochtitlan quickly, he finally hurried ahead with his best soldiers. The slow column of allies and the porters then marched behind, escorted by comparatively few Spanish soldiers (Cortes later spoke in a letter of 300 native allies and 50 Spanish soldiers). This second group was attacked by warriors from Texcoco on their way to Tenochtitlan, who took all of them prisoner. The warriors took revenge for the murder of their ruler Cacamatzin .

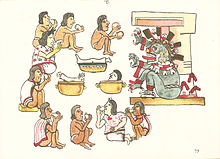

The 550 prisoners were brought to Zultepec and there sacrificed to the gods . The killing dragged on for six months. According to archaeologist Enrique Martínez Vargas, prisoners were held in prison cells with no doors and food was thrown through small window openings. Before daybreak, Aztec priests who had come from Tenochtitlan selected some prisoners to be sacrificed that day. As part of the ritual rituals, some of the corpses were then also eaten.

The victims were Spaniards, African slaves, mulattos , mestizos , Taíno from the Greater Antilles , Totonaks , Tlaxcalteks , indigenous people from the area of Tabasco and Mayas . Among them were women, including pregnant women, and children. According to the archaeologist Enrique Martínez Vargas, remains of about fifty women and ten children have been found. The European women among the victims were the first Europeans to arrive in Mexico, because Cortés only took men with him on his expedition in 1519. It was not until the second landing on Mexican soil in 1520 that there were women in the entourage of Pánfilo de Narváez.

destruction

After hearing of the massacre in 1521, Cortés dispatched a punitive expedition under the command of Gonzalo de Sandoval to destroy the place. When the residents of Zultepec heard of the approaching Spaniards, they threw the remains of the human sacrifices into dry cisterns , as well as the looted objects such as weapons, bridles, nails and jewelry. This later enabled the rich yield in archaeological research. As Cortés later reported, the residents tried to flee, but the Spaniards caught up with them and killed many of them. The rest of the population was enslaved and the place was abandoned. According to the chief archaeologist, the settlement was completely burned down and razed to the ground by the Spanish.

The ruins of Zultepec were henceforth referred to by the locals with the Nahuatl name Tecoaque , which means "place where they ate them". The original name Zultepec was used in documents from the 16th and 17th centuries, then it only lived on in the name of the immediately neighboring, younger village of San Felipe Sultepec. As a result of these name changes, knowledge of the location of the former settlement of Zultepec was lost and remained unclear until the end of the 20th century.

Historical sources

Cortés reported on the events in two of his letters to the Spanish King Charles : in the second letter of October 30, 1520 and in the third letter of May 15, 1522. In the third letter he wrote that the natives sacrificed his people and gave them their hearts would have taken. That is why he ordered Gonzalo de Sandoval to destroy that "large town". He reported some details, for example that Sandoval found the message written in chalk on a wall: "This is where the hapless Juan Yuste was trapped".

The later chronicles of Francisco López de Gómara ( Historia general de las Indias , 1551) and Bernal Díaz del Castillo ( True History of the Conquest of New Spain , 1568) are also historical sources. The Spanish reports are, however, unreliable in detail. For example, Cortés and the chroniclers did not mention that women were also among the victims. However, the archaeologists found the remains of around 50 female victims (as of 2015).

Archaeological site

The archaeological site was given the younger name Tecoaque at the beginning of the excavations . It was only in the course of research that it turned out that it was the former settlement of Zultepec. As a result of this discovery, Enrique Martínez Vargas, one of the archaeologists in charge, suggested that the site be renamed Zultepec in 2001 . A double name is often used: Zultépec-Tecoaque or Tecoaque-Zultepec .

The settlement area of Zultepec extended over an area of 32 hectares. The core zone has been thoroughly investigated since 1993. The foundations of some houses have been raised by walls so that structures are more visible. The most important building is a round pyramid in the style of Cuicuilco , which is associated with the wind god Ehecatl , a form of Quetzalcoatl .

During the excavations, over 10,000 objects were recovered by 2006 and a total of almost 15,000 objects by 2010. The first excavation period ended in 2010 and the finds were examined in the following years. At least 200 objects can be clearly assigned to Europeans. The archaeologists found evidence of human sacrifices and the remains of European farm animals such as pigs and goats. Some human bones showed knife marks, changes caused by cooking and even tooth prints - clear indications of cannibalism . The pigs, on the other hand, were killed but not eaten.

Fourteen skulls lacking the lower jaw were found in one cavity. The characteristic perforations on both temples prove that the skulls were intended for presentation on a tzompantli . The skulls are from seven women and seven men between the ages of 20 and 35 years. The investigation revealed that eight of the victims came from different areas of Mexico, five victims came from Europe, and one skull was from a mulatto woman . Various ritual objects were also found, including a flint knife that was hidden in the stairwell area of the round temple. It is with this knife that the sacrifices were apparently performed.

The excavations continued in 2015 with the aim of reconstructing the prisoners' living conditions more precisely. After the new excavation campaign has been completed, around 20 percent of the entire site should be explored. In November 2015, the archaeologists found the skeleton of a high-ranking, around 25-year-old member of the local Acolhua people , as well as vertebrae and ribs of at least three children in a cistern used as a grave . The tracks suggest that body parts were boiled for one of the children. In the same “burial cistern ” there was also a throne made of Tezontle stone and an engraved cylindrical stone, which was probably dedicated to the pulque god Ometochtli.

The sacrificial cult of the Aztecs was already known before the excavations in Zultepec-Tecoaque, as was the fact that in some cases very many victims were executed. The particular importance of the site is primarily that the massive capture of Spaniards and their allies has been archaeologically proven. In addition, the question of whether the Aztecs had practiced ritual cannibalism has long been a matter of dispute . The finds in Zultepec-Tecoaque prove this with great clarity.

See also

Web links

- Tecoaque unesco.org (English)

- Zona Arqueológica de Tecoaque Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (Spanish)

- Sultepec - Tecoaque Tlaxcala State Tourism Website (Spanish)

- Aztec Massacre TV documentary, 2008, PBO (52:20 min.). For criticism of this film, see the article on the film in the English Wikipedia.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Tecoaque, UNESCO description

- ↑ Tecoaque / Zultepec - map with altitude information

- ↑ a b c Ricardo Pacheco Colin: Encuentran restos del sacrificio de españoles durante la Conquista , in: La Crónica del Hoy of September 21, 2003, accessed on March 6, 2015 (Spanish).

- ↑ a b c d e f g Enrique Martínez Vargas, Ana María Jarquín Pacheco: El Tzompantli de Zultépec-Tecoaque , in: Letras Libres No. 133 from January 2010, accessed on March 6, 2015 (Spanish).

- ↑ a b c d e David Usborne: Montezuma's revenge: Cannibalism in the age of The Conquistadors , in: The Independent, August 25, 2006, accessed March 6, 2015.

- ↑ a b c d e Excavaciones revelan sacrificio de españoles en ruinas de Tlaxcala elfinanciero.com.mx, October 9, 2015

- ^ A b Ana Mónica Rodriguez Enviada: Hallazgo arqueológico confirma sacrificios humanos prehispánicos , in: La Jornada of August 2, 2006, accessed on March 6, 2015 (Spanish).

- ↑ Nuevas excavaciones revelan cómo los aztecas sacrificaban a los españoles vice.com, November 30, 2015

- ^ Zona Arqueológica de Tecoaque Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia

- ↑ Example for the name form Zultépec-Tecoaque website of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia

- ↑ Example of the alternative spelling Sultepec-Tecoaque tourism website of the state of Tlaxcala

- ↑ Example for the name form Tecoaque-Zultepec at mexicoescultura.com

- ↑ a b Information on the current excavation campaign Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, June 11, 2015 (Spanish)

- ↑ Aerial photo of the excavation site (previously excavated core area)

- ↑ a b c Dig reveals details of Spanish captives' fate Mexico News Daily, October 13, 2015

- ↑ Evidence of pulque god found in Tlaxcala Mexico Daily News, November 19, 2015

- ↑ Dig reveals details of Spanish captives' fate Mexico News Daily, October 13, 2015. Quoting: “The Tecoaque discoveries are relevant to the history of the conquest because for the first time there is actual archaeological evidence of resistance to the Spanish onslaught by native people. "