Crowding (seeing)

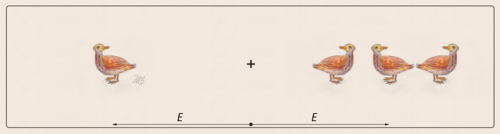

Crowding , or the crowding effect, describes the perceptual phenomenon that the visual recognition of a shape is made more difficult by the presence of neighboring shapes. Conversely, spatially isolated shapes or objects are easier to recognize. Crowding is particularly pronounced in peripheral vision , but is also effective in central vision. The extent (unlike visual acuity ) is largely independent of the size of the shapes and is essentially determined by the distance between the neighboring shapes. For a long time it was assumed that crowding was primarily a phenomenon of peripheral vision . In the meantime it is clear that it is of decisive importance everywhere in the visual field and as a limitation it is usually more significant than the visual acuity (decreasing outward in the visual field). In central (foveal) vision, it is even particularly important insofar as it represents the decisive limitation when reading .

The crowding phenomenon is particularly pronounced in amblyopia and was first mentioned and quantified in this context. Children up to around the age of 8 also have a stronger crowding effect, and this may be the reason why children's books need larger fonts.

The neural mechanisms of the visual system that are crowded are not found in the retina of the eye, but in the visual cortex of the brain ( visual cortex ). Related phenomena are lateral masking , lateral inhibition , lateral interference and contour interaction , which, however, presumably have different mechanisms.

Bouma's Law

The distance between neighboring patterns (so-called flankers) above which no more crowding occurs is called the critical distance . In 1970, Herman Bouma described a fundamental law for crowding that relates to the critical distance. According to Bouma, this is about half the angle of eccentricity. So z. E.g. a letter is presented at 2.5 ° eccentricity - this is the approximate edge of the fovea. - so the critical distance is 1.25 °. If the flankers are closer, crowding occurs. According to more recent studies, the factor is somewhat lower than ½, at around 0.4 times the eccentricity angle.

history

According to current knowledge, with a few exceptional situations, crowding is the decisive limitation of human form perception and can be demonstrated in the simplest possible way. It is therefore noteworthy that it has been scientifically overlooked for so long, and that the cause of the reduced ability to recognize patterns has always been (mostly incorrectly, as we now know) seen in reduced visual acuity. The perception of a word in peripheral vision was already described by Alhazen in the 11th century as "confused and obscure". In 1738, James Jurin describes phenomena of "indistinct vision" which, from today's perspective, can be viewed as crowding in two cases. In 1857 the ophthalmologists Hermann Aubert and Richard Förster described the perception of two adjacent points in indirect vision as "very peculiarly indeterminate as something black, the shape of which cannot be further specified". It should be noted that in no case were the descriptions that are often used today but not very accurate as “fuzzy” or “distorted”.

But crowding itself (i.e. the difference between single and multiple letters or shapes) went unnoticed until the 20th century. In 1924, the Gestalt psychologist Wilhelm Korte was the first to extensively investigate the phenomena of shape recognition in indirect vision. Around this time, crowding was also recognized in optometry and ophthalmology among amblyopic test persons in connection with the use of eye test tables , as can be deduced from a remark by the Danish ophthalmologist Holger Ehlers in 1936. James A. Stuart and Hermann M. Burian (Iowa) first systematically investigated this in 1962. In foveal vision, the related phenomenon of contour interaction was described at about the same time (Merton Flom, Frank Weymouth & Daniel Kahneman , 1963). Herman Bouma described Bouma's law (initially as a rule of thumb) in 1970, but initially little attention was paid to the work; In the next three decades the phenomenon was studied under different terms, mainly in experimental psychology. Only then did the topic of crowding become increasingly widespread in perception research (Levi et al. 1985; Strasburger et al, 1991; Toet & Levi, 1992, Pelli et al., 2004).

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Hans Strasburger: Seven myths on crowding and peripheral vision . In: i-Perception . 11, No. 2, 2020, pp. 1-45.

- ↑ Dennis M. Levi: Crowding - an essential bottleneck for object recognition: a minireview . In: Vision Research . 48, No. 5, 2008, pp. 635-654.

- ^ H. Strasburger, I. Rentschler, M. Jüttner: Peripheral vision and pattern recognition: a review . In: Journal of Vision . 11, No. 5, 2011, pp. 1-82.

- ^ DG Pelli, KA Tillman, J. Freeman, M. Su, TD Berger, NJ Majaj: Crowding and eccentricity determine reading rate . In: Journal of Vision . 7, No. 2:20, 2007, pp. 1-36.

- ↑ Holger Ehlers: The movements of the eyes during reading . In: Acta Ophthalmologica . 14, 1936, pp. 56-63.

- ↑ a b J.A. Stuart, HM Burian: A study of separation difficulty: its relationship to visual acuity in normal and amblyopic eyes . In: American Journal of Ophthalmology . 53, 1962, pp. 471-477.

- ↑ J. Atkinson, E. Pimm-Smith, C. Evans, G. Harding, O. Braddick: Visual crowding in young children . In: Documenta Ophthalmologica Proceedings . 45, 1986, pp. 201-213.

- ^ Herman Bouma: Interaction effects in parafoveal letter recognition . In: Nature . 226, 1970, pp. 177-178.

- ↑ To illustrate: A thumb, viewed at arm's length, has a viewing angle of approximately 2.5 °. So two thumb widths roughly correspond to the size of the fovea

- ↑ H. Strasburger, NJ Wade: James Jurin (1684-1750): A pioneer of crowding research? . In: Journal of Vision . 15, No. 1: 9, 2015, pp. 1-7.

- ^ HR Aubert, CFR Förster: Contributions to the knowledge of indirect vision. (I). Studies on the sense of space in the retina . In: Archives for Ophthalmology . 3, 1857, pp. 1-37.

- ^ H. Strasburger: Dancing letters and ticks that buzz around aimlessly - On the origin of crowding . In: Perception . 43, No. 9, 2014, pp. 963-976.

- ↑ For an overview s. Fig. 19 in: Hans Strasburger: Seven myths on crowding and peripheral vision . In: i-Perception . 11, No. 2, 2020, pp. 1-45.