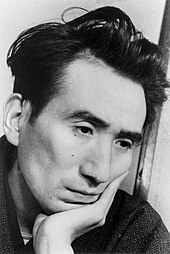

Dazai Osamu

Dazai Osamu ( Japanese 太宰 治 ; born June 19, 1909 in Kanagi , today: Goshogawara , Aomori Prefecture ; † June 13, 1948 in Tokyo ; actually Tsushima Shūji , 津 島 修治 ) was a Japanese writer.

Life

Dazai was born the tenth of eleven children. His father, Tsushima Gen'emon , was a wealthy landowner and a member of the Japanese parliament . Tsushima Gen'emon was elected to the House of Commons when Dazai was three years old and ten years later to the House of Lords. The house in which Dazai was born did not count 19 rooms, kitchen and service rooms. Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit believes that Dazai had to play an outsider role in his family and only built an emotional relationship with his nanny Take. He read a lot and started writing stories at the age of 13.

A decisive experience in his youth was the suicide of his idol Akutagawa Ryūnosuke in 1927. Dazai studied French literature at Tokyo University (1930 to 1935). His ambition was less for academic success and so he began to spend more and more time writing, briefly joining a Marxist movement and finally dropping out.

In 1933 he published the first short stories and adopted the pseudonym "Dazai Osamu". He only found general recognition as a student of Ibuse Masuji from 1935 onwards. Between 1928 and 1935 he made three suicide attempts. In 1928 he tried to kill himself with an overdose of sleeping pills, in 1930 he allied himself with the 19-year-old waitress Shimeko, both wanted to go into the water together: the girl died, Dazai survived and had to answer to the police and finally he failed in 1935 trying to hang yourself. Three weeks after his last failed suicide attempt, he developed appendicitis and had to undergo an operation. Treatment in the hospital made Dazai addicted to pain medication. He fought the addiction for over a year and was finally taken to an institution in October 1936, where he decided to go into cold withdrawal . He allows his experiences there to flow into the book Drawn . The treatment lasted over a month; meanwhile, his first wife, Oyama Hatsuyo ( 小山 初 代 ), was cheating on him with a close friend. When Dazai found out about the affair, the couple tried to commit suicide together. When that did not succeed, they divorced. Dazai married Ishihara Michiko ( 石 原 美 知 子 ) on January 8, 1939 . The couple traveled extensively and he wrote literary travelogues. Their daughter Sonoko was born on June 7, 1941. When Japan entered World War II , Dazai was not drafted due to a chest pain. During the war years, his work was very slow, not least because of the increasing censorship that prevented the pressure on his work. His house was bombed several times. The son Masaki was born on August 10, 1944. Due to the bombing, the family left the city in April 1945 and when she returned in November, Dazai began a relationship with several women. In 1947 two daughters of Dazai were born: the second legitimate daughter Satoko (later Yūko ( 佑 子 )) on March 30th, and a mistress of Dazai, Ōta Shizuko, gave birth to a girl called Haruko on November 12th .

After the Second World War, his writing style changed and increasingly reflected the problems, rebellions and suicidal thoughts of his youth.

On June 13, 1948 Dazai drowned himself with Yamazaki Tomie ( 山崎 富 栄 ), his lover, in the Tama Canal ( 玉川 上水 , Tamagawajōsui ). His body was recovered on June 19, his 39th birthday. He left an unfinished serial novel called Guddo bai .

His urn was buried in the Zenrin-ji ( 禅林 寺 ) Temple in Mitaka , Tokyo Prefecture. The house where Dazais was born now houses a museum dedicated to his life and work as a Dazai Osamu memorial . In memory of the writer, the Dazai Osamu Prize is awarded annually to young writers by the city of Mitaka and the Chikuma Shobo publishing house .

Family tree Dazais

- Dazai's older brother Tsushima Bunji was mayor of Kanagi and later governor of Aomori .

- His daughter Yūko Tsushima also became a writer and published her first story in 1969. She died in 2016 at the age of 68.

- Yūji Tsushima is the husband of Dazai's daughter Sonoko.

| Tsushima Gen'emon | Tane | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bunji | Ōta Shizuko | Dazai Osamu | Ishihara Michiko | Eiji | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kōichi | ? | Tazawa Kichirō | Ōta Haruko | Yūji | Sonoko | Masaki | Yūko | Kazuo? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kyōichi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Works (selection)

Dazai was strongly influenced by Shishōsetsu (first- person novel). According to James A. O'Brien, he was more interested in personal, archetypal experiences than in creating fictional characters. His work is highly subjective.

However, this does not mean that his work is purely autobiographical. Rather, he invented events for the purpose of emotional communication. An influence of proletarian literature is identified in his work, which was particularly evident in the period before 1945. This is attributed to Dazai's origin and the attractiveness of the Hōgan Biiki . Hōgan Biiki ( 判官 贔 屓 ), which means to stand on the side of the loser, also explains Dazai's change of position after the end of the Second World War. In The Setting Sun he is now on the side of the landowners.

Dazai dealt with universal subjects and used seemingly simple language. But his idiosyncratic humor made it difficult to translate his work. The sadness that pervades his writing is always balanced by the awareness that this is an absurd world.

The creation of a fictional world and a framework plot were the main problems Dazai had when writing, but he was aware of them. He therefore resorted to works by Saikaku and Schiller among others .

Donald Keene compares Dazai's talent to that of a great cameraman who sharpens his eyes on moments in his own life, but composition and selection make his work a creative work of art.

- 1934 ロ マ ネ ス ク (Romanesuku)

- 1935 ダ ス ・ ゲ マ イ ネ (Dasu gemaine) dt. The common and other stories , 1992

- 1935 逆行 (Gyakkō), German reverse gear

- 1936 晩 年 (Bannen), German Last Years , short story collection

- 1937 音 に つ い て (Oto ni tsuite), German from the lute

- 1939 愛 と 美 に つ い て (Ai to bi ni tsuite), dt. Of love and beauty

- 1940 嘘 (Uso)

- 1940 走 れ メ ロ ス (Hashire Merosu), German run, Melos, run!

- 1940 女 の 決 闘 (Onna no kettō)

- 1941 新 ハ ム レ ッ ト (Shin Hamuretto), German. The new Hamlet

- 1945 惜別 (Sekibetsu)

- 1946 パ ン ド ラ の 匣 (Pandora no hako)

- 1947 斜陽 (Shayō), German The setting sun

- 1947 ヴ ィ ヨ ン の 妻 (Biyon no tsuma)

- Film by Kichitarō Negishi, screenplay: Yōzō Tanaka, 2009

- 1947 ト カ ト ン ト ン (Tokatonton)

- 1948 人間 失 格 (Ningen shikkaku), German drawn

- 1948 グ ッ ド ・ バ イ (Guddo bai) - unfinished (film Goodbye, by Koji Shima, with Hideko Takamine, Masayuki Mori, Masao Wakahara, Tamae Kiyokawa, 1949)

German translations

- Dazai Osamu: The mean . Iudicium, Munich 1992, p. 313 (Japanese: ダ ス ゲ マ イ ネ . Translated by Stefan Wundt).

- Dazai Osamu: Drawn . Insel, Frankfurt 1997, p. 150 (Japanese: 人間 失 格 . Translated by Jürgen Stalph).

- Dazai Osamu: A visitor . In: Nippon. Modern stories from Japan from Mori Ogai to Mishima Yukio . Diogenes, Zurich 1965, p. 47–58 (Japanese: 親友 交 歓 . Translated by Monique Humbert).

- Dazai Osamu: Villon's wife . In: Eduard Klopfenstein (Ed.): Dreams from ten nights. Japanese narratives of the 20th century . Theseus, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-85936-057-4 , p. 227–250 (Japanese: ヴ ィ ヨ ン の 妻 . Translated by Jürgen Berndt).

- Dazai Osamu: Wait . In: Booklets for East Asian Literature . 1983, p. 61–63 (Japanese: 待 つ . Translated by Jürgen Stalph).

- Dazai Osamu: The setting sun . Hanser, Munich 1958, p. 167 (Japanese: 斜陽 . Translated by Oscar Benl).

- Dazai Osamu: leaves . In: Objection of Decadence . Angkor (Edition Nippon), Frankfurt 2011, p. 133–146 (Japanese: 葉 . Translated by Alexander Wolmeringer).

- Dazai Osamu: Black Diary . In: Objection of Decadence . Angkor (Edition Nippon), Frankfurt 2011, p. 147–157 (Japanese: め く ら 草 子 . Translated by Alexander Wolmeringer).

- Dazai Osamu: The train . In: Objection of Decadence . Angkor (Edition Nippon), Frankfurt 2011, p. 158–162 (Japanese: 列車 . Translated by Alexander Wolmeringer).

- Dazai Osamu: trinkets . In: Objection of Decadence . Angkor (Edition Nippon), Frankfurt 2011, p. 163–169 (Japanese: 玩具 . Translated by Alexander Wolmeringer).

- Dazai Osamu: The criminal . In: Objection of Decadence . Angkor (Edition Nippon), Frankfurt 2011, p. 170–183 (Japanese: 犯人 . Translated by Alexander Wolmeringer).

- Dazai Osamu: The visitor . In: Objection of Decadence . Angkor (Edition Nippon), Frankfurt 2011, p. 184–193 (Japanese: た ず ね び と . Translated by Alexander Wolmeringer).

- Dazai Osamu: I can speak . In: Booklets for East Asian Literature . No. 50 . Iudicium, Munich 2011, p. 108–110 (Japanese: ア イ キ ャ ン ス ピ ー ク . Translated by Matthias Igarashi).

- Dazai Osamu: The lamp . In: Booklets for East Asian Literature . No. 50 . Iudicium, Munich 2011, p. 111–117 (Japanese: 灯 篭 . Translated by Matthias Igarashi).

- Dazai Osamu: From women . In: Mountain Range in the Distance: Encounters with Japanese Authors and Texts . Edition Peperkorn, Thunum 2002, p. 159–168 (Japanese: 雌 に 就 い て . Translated by Siegfried Schaarschmidt).

- Dazai Osamu: Sado . In: Booklets for East Asian Literature . No. 35 . Iudicium, Munich 2003, p. 47–61 (Japanese: 佐渡 . Translated by Jutta Marlene Vogt).

- Dazai Osamu: The Devils of Tsurugi Mountain. Narratives . Translated and with an afterword by Verena Werner. be.bra verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-86124-915-3 .

- Dazai Osamu: Old friends . Cass, Löhne 2017 (Japanese: Shin'yū-kōkan . Translated by Jürgen Stalph).

literature

- Phyllis I. Lyons, The Saga of Dazai Osamu: A Critical Study With Translations , Stanford, Calif .: Univ. Press, 1985. ISBN 0-8047-1197-6 .

- James A. O'Brien, Dazai Osamu , Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1975. ISBN 978-0-8057-2664-0 .

- Alan Wolfe, Suicidal Narrative in Modern Japan: the Case of Dazai Osamu , Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 1990. ISBN 0-691-06774-0 .

Web links

- Digitized works at Aozora Bunko (Japanese)

- Dazai Museum (Japanese, English, Korean, Chinese)

- Reviews of the works: The Common and Other Stories, The Setting Sun, The Devils of Tsurugi Mountain, Objection of Decadence, Drawn

Remarks

- ↑ The listing follows the database of the Japan Foundation

Individual evidence

- ↑ Entry on Shoyoukan on the region's attractions website

- ↑ Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit, follow-up , in: Dazai Osamu, Geanned , Frankfurt / Main, Leipzig 1997, pp. 137–151, p. 140.

- ↑ Irmela Hijiya-Kirschnereit, follow-up , in: Dazai Osamu, Geanned , Frankfurt / Main, Leipzig 1997, pp. 137–151, p. 139.

- ↑ Sato, Takanobu ( 佐藤 隆 信 ): 太宰 治 (= 新潮 日本 文学 ア ル バ ム 19 ). Shinchosha, Tokyo 1983, ISBN 978-4-10-620619-1 , pp. 108 .

- ^ Ivan Morris, Review of Dazai Osamu. by James A. O'Brien , The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 35, No. 3 (May 1976), pp. 500-502, pp. 500.

- ^ Ivan Morris, Review of Dazai Osamu. by James A. O'Brien , The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 35, No. 3 (May 1976), pp. 500-502, p. 501.

- ^ Ivan Morris, Review of Dazai Osamu. by James A. O'Brien , The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 35, No. 3 (May 1976), pp. 500-502, p. 501.

- ^ Ivan Morris, Review of Dazai Osamu. by James A. O'Brien , The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 35, No. 3 (May 1976), pp. 500-502, p. 502.

- ↑ Donald Keene, Translator's Introduction , in: Dazai Osamu, No Longer Human , New Directions, 1997, pp. 1 - 10, p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8112-0481-1

Web links

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Dazai, Osamu |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | 太宰 治 (Japanese); 津 島 修治 (real name, Japanese); Tsushima Shūji (real name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Japanese writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 19, 1909 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Kanagi (today: Goshogawara ) |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 13, 1948 |

| Place of death | Tokyo |