Dark duck

| Dark duck | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dark Duck ( Anas rubripes ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Anas rubripes | ||||||||||||

| Brewster , 1902 |

The dark duck ( Anas rubripes ) is a North American species from the duck family . It represents an exception within the real ducks because it does not show any sexual dimorphism . Both sexes are similar in appearance to the females of the mallard . However, they are generally a little darker in color and have noticeably light cheeks and sides of the neck. Occasionally it is classified as a subspecies of this species because of its many similarities with the mallard. However, studies on 58,000 shot animals of both species revealed only 318 intermediate hybrids. Today, however, the mallard is increasingly penetrating the traditional distribution areas of the dark duck, which increases the proportion of hybrids.

description

General characteristics and likelihood of confusion

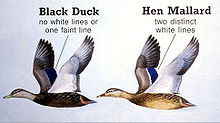

The body length of the dark duck is 53 to 61 centimeters. Adult dark ducks weigh an average of 1090 grams in autumn. Both sexes show a similarity to the mallard . In the male, however, the overall plumage including the rudder and scapular plumage is black-brown and only lined with a narrow clay color. The sides of the head and neck are lightened. The females of the dark duck are even more similar to those of the mallard due to their wider feather edges. In both sexes, however, the wing mirror is dark purple and framed by wide black bands. The white that is characteristic of mallards is missing.

Description of the plumage

Adult male ducks have a yellow bill and dark body plumage, from which the head and neck are contrasted by a lighter color. A dark line of color runs from the upper base of the beak over the eye to the back of the head. The cheeks show fine brown dots. The legs are orange and the eyes are dark. The gender dimorphism is only slightly pronounced. Adult females are similar to males. However, the legs of the male are a little brighter orange than those of the females. In contrast to the mallard, both of them lack the white border of the wing surface . There are individuals in whom some white appears on the edge of the mirror. However, this is limited to the very end of the mirror. There is also a similarity to the North American Florida duck . This non-migrating duck species is only found on the Florida peninsula and in the western coastal area of the Gulf of Mexico, so that the ranges of these two species do not overlap.

Basically, this species has noticeable individual differences in body size and plumage. As a rule, dark ducks are somewhat larger in their northern range. The bridle of the eye in the male varies in length and can be seen differently. Like the neck feathers, it often has a greenish sheen. The extent to which these variations in body plumage can be attributed to hybridization with mallards has not yet been adequately investigated.

Both sexes have brown-orange to coral-red legs with darker webbed feet. The beak is yellowish with a dark nail and turns olive towards the base of the beak. The eyes are brown.

In flight, the white lower wings stand out from the dark sides of the body. The voice is very similar to that of the mallard, but the call of the female is a tone darker.

distribution and habitat

Dark ducks are a purely North American species of duck. The breeding areas of the dark duck are lakes, ponds, rivers and wetlands in eastern Canada from Hudson Bay to Newfoundland and south across the Great Lakes to New York and the North Carolina coast. In contrast, it is absent in western North America. Dark ducks occasionally appear as a stray visitor in the Azores, Ireland, Great Britain and Sweden. Similar to the cap saw , however, observations always assume that they are so-called captive refugees. There has also been crossbreeding with mallards in Great Britain. The males of the dark duck move very far on their moulting and then also appear far outside their breeding area. They can then also be found in the treeless subarctic, in prairies and in parklands of central North America.

Dark ducks are a very adaptable species of ducks that use a variety of different types of water. However, it prefers bodies of water in forest regions. The ornithologists James Gooders and Trevor Boyers suspect that the dark duck in this habitat is not exposed to excessive competition from the more assertive mallard. In the past, the habitats of these two species of ducks were more differentiated from one another. While the dark duck was mainly found on shady forest lakes in eastern North America , the lighter feathered mallard was mainly found on the lakes of the prairie landscape. Due to logging and afforestation, these habitats have mixed up and hybridization occurs in the wild .

Dark ducks are partial migrants. Some populations move to the eastern states of the USA in winter and then prefer to stay in coastal regions. Other populations can be found in the Great Lakes region year-round.

Food and subsistence

Dark ducks are an omnivorous species of duck. The food composition depends on what the habitat offers. The proportion of invertebrates in the food composition of dark ducks living in coastal regions is generally greater than that of those who continue to live inland. Basically, dark ducks consume more animal food than mallards. There are also seeds from grasses and sedges, leaves and roots from aquatic plants. Animal diet plays an important role, especially in summer. In a study of breeding birds in Maine, small crustaceans and insects provided up to 74 percent of the diet.

Reproduction

In the courtship repertoire, too, the dark duck shows a lot in common with the mallard. For example, the dark duck also has the grunt whistle, which is a characteristic courtship gesture in the mallard. The courtship starts in August and has its first peak in late autumn. However, the peak of courtship falls between February and March.

The populations have a higher proportion of drakes. Therefore, especially in the first year of life, many of the drakes remain unmated. However, there is not such a strong promiscuity as with the mallard. There is some evidence that the couples stayed together for several years. The nest is built by the female. It usually consists of just one recess. The nest lining consists of feathers and during the brood more downy feathers are added, as the female covers the nest with downs when it leaves the clutch. The clutch consists of seven to 11 eggs, which are creamy white. The female breeds alone. The chicks hatch after a breeding period of 23 to 25 days. Newly hatched chicks weigh an average of 31 grams. Basically, the loss rate of clutches is very high and is more than 50 percent in some regions. In Chesapeake Bay , for example, only 38 percent of the nests hatched. Clutches are lost through flooding and human disturbance. Predators that eat the eggs and also kill breeding females include birds of prey, foxes and raccoons. After a clutch loss there are up to three times lagging behind, whereby this occurs more in older females than in first-brooding females.

Duration

The dark duck population is declining. Long-term research suggests that this species has been declining at an average of three percent annually since the 1950s. The North American Waterfowl Management Plan provides special protection measures for this species for this reason. Habitat changes are the cause of the population decline. These include, in particular, extensive deforestation, which promotes the spread of the more competitive mallard.

Keeping in human care

Because of their mallard-like appearance, dark ducks are relatively seldom kept by breeders or shown in zoos. The Berlin Zoo kept this species for the first time in 1874. The first breeding of this species was probably made in the 20th century. Offspring for North America from 1909 and for the London Zoo are known. The British Wildfowl Trust has also had this species since 1950 .

supporting documents

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gooders and Boyer, p. 53

- ^ Kolbe, p. 208

- ^ Kear, p. 510

- ↑ Kolbe, p. 207

- ↑ Gooders and Boyer, p. 53

- ↑ Christopher S. Smith: Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl , Wilderness Adventure Press, Belgrade (Montana) 2000, ISBN 1-885106-20-3 , pp. 58 and 60

- ↑ Kear, p. 509

- ↑ Kear, p. 509

- ↑ Christopher S. Smith: Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl , Wilderness Adventure Press, Belgrade (Montana) 2000, ISBN 1-885106-20-3 , p. 60

- ↑ Gooders and Boyer, p. 53

- ^ Kear, p. 510

- ^ Kear, p. 510

- ↑ Gooders and Boyer, p. 53

- ^ Kear, p. 510

- ↑ Kear, p. 511

- ↑ Gooders and Boyer, p. 55

- ↑ Gooders and Boyer, p. 55

- ^ Kear, p. 510

- ↑ Kear, p. 512

- ↑ Gooders and Boyer, p. 55

- ↑ Kear, p. 512

- ↑ Kear, p. 512

- ↑ Kear, p. 512

- ↑ Kear, p. 513

- ↑ Kolbe, p. 209

literature

- John Gooders and Trevor Boyer: Ducks of Britain and the Northern Hemisphere , Dragon's World Ltd, Surrey 1986, ISBN 1-85028-022-3

- Janet Kear (Ed.): Ducks, Geese and Swans. Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-19-854645-9 .

- Hartmut Kolbe; Die Entenvögel der Welt , Ulmer Verlag 1999, ISBN 3-8001-7442-1

Web links

- Anas rubripes in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed on December 22 of 2008.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings for Anas rubripes in the Internet Bird Collection