French accordion

As a French accordion , both diatonic and chromatic hand-drawn instruments were and are being built.

history

In 1831 a diatonic accordion was brought to Paris from the workshop of Cyrill Demian . Napoleon Fourneux was the first to succeed in the replica. The original was still very much seen in his first instruments. The reed plates were also mounted flat on an insert. The key assignment differs from the usual diatonic assignment. The clavis and the arrangement of the keyboard were also slightly different from similar instruments from Vienna. One quickly tried to find a chromatic arrangement.

A dispute about how the instrument should be played began very quickly, as reported by music magazines such as Le Menestrel in 1834. The newspaper also mentions that M. Reisner wrote a school for the instrument, an “instruction on the accordion To learn to play with eight keys: […] You play the instrument with your right hand. [...] The two flaps on each side serve [...] to cancel the harmony. "

A melody instrument came to Paris. At that time, many different key assignments were tried out in Vienna, some instruments simply had the tones installed the other way round and the assignment was not always the same in every case. It is therefore not absolutely certain that a purely diatonic instrument came to Paris.

Since two schools for learning the game were published very early, we now know very well about the development of the instruments in Paris.

The Parisian accordion makers quickly gained a good name and contributed significantly to the further development of the instruments. In the Musical Instrument Museum in Markneukirchen , some well-preserved objects from the following years can be seen; These instruments were probably acquired very early on by German accordion producers for study purposes.

An exhibit also shows how the French implemented the register switch. This was not done, as is common today, with sliders in the air, but with a mechanism that prevented the unused tongues from swinging. This lever mechanism connected a common axis with levers provided with felt pads, each of which pressed on a tone tongue.

In general, the invention of several reeds with the same pitch, but somewhat out of tune, is attributed to the French (musette). Viennese instruments were initially offered with so-called organ tuning or with triple organ tuning , which was an octave tuning , i.e. several reeds per key offset by octaves.

construction

The instruments from this period were still very handy, hardly larger than the instruments that Demian built in Vienna. From the outward appearance, however, their French origin is unmistakable. The wooden frame was mostly curved and provided with baroque paintings, as was the French art taste of the time. The keys or the clavis were led in two rows, flat and square, with clavis wires to the keys. The clavis were covered with mother-of-pearl. The round flaps were also made of mother-of-pearl. The flaps were not covered.

It was noticeably different that the keys in the second row led through the fingerboard to the back and opened a second row of flaps there. This principle is found again today in the bayan . The keyboard of the Bajan has also been moved further forward and some rows of keys lead to the back of the keyboard. It is also interesting that the seventh key in the second row was split in the middle.

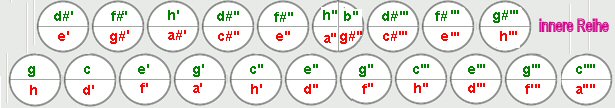

From this period there are smaller instruments that have two rows with eight keys each or larger two rows with 14 keys in the first row and five divided keys and eight undivided keys in the second row. The system remains the same, only the range is extended upwards to c '' '' '. The structure of these instruments also favored the vibration behavior of the high tones. The lowest note was the f.

At that time, the instrument makers were proficient in the precise manufacture of reed plates to an extent that is still hard to imagine today.

Key assignment

In 1845 there were a number of producers in France: Alexandre, Fourneaux, Jaulin, Lebroux, Neveux, Kasriel, Leterme, Reisner, Busson, M. Klaneguisert. They all built two models at the time:

- without semitones - i.e. diatonic

- with semitones - chromatic and alternating tones

The bass side only had two basses, so it was hardly developed. The “mutation”, two sliders that made chords sound, was no longer incorporated at that time, as was the case in Vienna.

The war of 1870 and 1871 brought accordion production to an almost complete standstill.

The classification of the chromatic key assignment was not yet completed for some time. Around 1890 there was the diatonic scale in the first row and the missing semitones with some repetitions of the first row in the second row. It is interesting in this context that the Irish key assignment today with C, C # largely corresponds to this assignment. Basses were not built in; the flaps on the bass side were air flaps.

In the period that followed, the import of Italian instruments to France increased.

today

There are a few producers in France who make diatonic accordions. Bernard Loffet builds instruments with traditional key assignments like the Viennese models. Another company, Saltarelle, has all kinds of modern instruments produced in Italy according to their wishes and under their own name. Bertrand Gaillard builds (since 1981) instruments with a legendary reputation, only to order and with long waiting times. L'Imaginaïre manufactures at a similarly high quality level. Other manufacturers are Eric Martin and Marc Serafini. Since there is no manufacturer in France, the reed plates and reeds come almost exclusively from Italy.

Chromatic accordions are produced by two companies; Cavagnolo in Lyon and Maugein in Tulle . The Manufacture d'accordéons Maugein was founded in 1919. In 2016 the company had 14 employees.

Web links

- Pictures of an accordion dated 1858 plus a school for it in English

- Website in French on history - very detailed, but faulty ( memento of October 4, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- Cavagnolo company portal

- Pictures of company tours Maugein and Cavagnolo

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Philippe Gloaguen, et al .: Le Routard - Le guide de la visite d'entreprise . No. 79/0425/0 . Hachette Livre, Vanves 2016, ISBN 978-2-01-323703-1 , pp. 28 f .