Heidegger's terminology

The terminology Heidegger came out mainly from the effort to break away from certain basic features and tendencies of philosophical traditions. Martin Heidegger wanted to develop a vocabulary that would do justice to his own theoretical concerns. This applies above all to his specific formulation of the question of being .

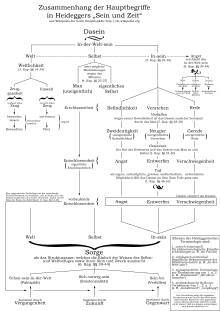

The article gives an overview of the most important terms and their change in meaning in the development of Heidegger's thinking over time. The place of their occurrence is also given in the complete edition .

Heidegger's handling of language

Since for Heidegger the history of occidental metaphysics is determined by the oblivion of being , he saw no possibility of connecting with its vocabulary. In this historical lack of language , Heidegger found himself exposed to the difficulty of developing a terminology for something that, in his opinion, has always remained unthought in the previous tradition.

Non-conceptual language

While the early Heidegger still tended to create neologisms in Sein und Zeit in order to do justice to this claim, his vocabulary later changed so that he borrowed terms from colloquial language, but strongly reinterpreted them. This changes again in later texts. Heidegger tends to non-conceptual language that partly on the poetic inspired. This Unbegrifflichkeit found, for example, in the vernacular, so there are "objects" - as the world, the history of man - of which we have neither an intuition (as the world is never given to us as a whole), nor are these " Objects “conceptually comprehensible. Heidegger's later concept of being can also be classified under such a group of “objects”.

Heidegger has developed various concepts to explain the problem of non-conceptuality and to propose alternatives. The main concern for him has always been that the philosophical concepts must concern people, they must grasp them . Since it is at the same time man who philosophizes, i.e. in whom metaphysics takes place, he is included in metaphysics and its concepts; metaphysics is therefore a conceptual thinking. (As in 1930; Heidegger will later reject the term “metaphysics” for his thinking.) In order for the person to be approached, indeed attacked, by the philosophical concepts, he must make them his own:

"The him [sc. Concepts opening up to people] can only be understood if they are not taken as meaning the properties and features of something that is present, but as an indication that understanding only emerges from the vulgar conceptions of beings and specifically turns into being there in them must transform. "

The terms do not point directly to an existing thing, but when they concern humans, they point to (temporal) structures that have no thing character. (See e.g. → Existence ). This is why a term only makes sense in a structural context with other terms. If you do not take the terms in the context to which Heidegger would like to refer, it quickly happens that you take them back to their old meaning and think that they indicate something that is already there.

It is true that, according to Heidegger, the problem of the conceptual context has been seen in the history of philosophy, which has led to the concepts being arranged in a system . However, since the context that determines human beings has grown historically, there cannot be an eternally valid system of philosophical concepts: "The historicity of existence even more than a systematics prevents any isolation and isolated replacement of individual concepts."

Rejection of imagery

Heidegger's language often has a metaphorical effect. However, since Heidegger himself did not want his use of language to be understood as metaphorical, this obvious contradiction remains the subject of research. On the one hand, it is assumed that the metaphors of the late Heidegger serve to constitute the "object" of which they speak, which cannot be grasped or conceptually understood, by speaking of it through them. An example of this is Heidegger's metaphor of light when he writes that “in the light of being, beings appear as being that it is.” The light that being throws on beings first makes them appear, that is, to be . What was previously dark is now visible. The clearing of being is the human being who, however, cannot control whether and how in the historical process the light of being falls into his clearing and lets beings be there. He can only keep himself open to the incident light. This whole process could not be said outside of the metaphor.

Heidegger himself always refused to describe his language as metaphorical. For example, in the "Letter on" Humanism "" he writes about his word about language as the house of being :

"Talking about the house of being is not a transfer of the image of the" house "to being, but rather from the properly conceived essence of being we will one day be better able to think what" house "and" dwell "are."

For Heidegger, taking up certain linguistic structures as metaphorical constructions represented a metaphysical error that he criticized, which assumes that an inside is transferred to an outside. The expression “a boring book” should not be understood as a metaphorical transport of something inside to outside. Heidegger would like to overcome the traditional opposition of subjective and objective, sensual and nonsensual. Therefore the destruction of the metaphor is an essential part of the metaphysics criticism: "The metaphorical exists", so Heidegger, "only within metaphysics."

Already in Sein und Zeit Heidegger refused to understand the “call of conscience” as a metaphor, which, like Kant's picture of conscience as a court of law, should be understood: “This characteristic of conscience as a call is by no means just an“ image ”, for example like the Kantian court conception of conscience. We just mustn't overlook the fact that the vocal announcement is not essential for the speech and thus also for the call. ”Heidegger did not see through what constitutes the human being in his world reference, the“ ec-static standing out ”, as primarily not through the rational-conceptual apprehension of individual beings determines. Instead, he saw what we fundamentally loading in dealing with the world 's true , in the mood. The mood precedes everything relating to individual things in the world. Nor is it aroused by a single inner-worldly thing, but is always ahead of and with us when we refer to something.

The basic mood, however, is not an inner attitude of the subject, but is itself essentially determined in relation to the world, since the human being, being ecstatic, is always 'outside'. It is a total sensation that also precedes individual sensory data. Because humans as ecstatic beings are “tuned” through their relation to the world, sensory data are also always immersed in this mood: Man does not receive any “raw data” like primitive animal organisms. Just as it depends on the situation, whether we perceive pain as excruciating or pleasurable, the basic mood precedes any individual experience. According to its origin, however, it protrudes into our cultural and historical background and is therefore broader and deeper than the mood in a situation. At Heidegger, the “sensory” organ for the mood is the heart. It is the organ of non-metaphysical thinking, because it does not limit our relation to the world to the sum of the individual sense organs and the data they provide, but rather makes it possible for us to hear, see and feel something that concerns us in our being :

“This hearing is not only related to the ear, but at the same time to the belonging of the human being to what his being is attuned to. The human being remains attuned to that from which his being is determined. In the determination the person is affected and called upon by the voice [...] "

For Heidegger, the metaphysical separation of sensual and nonsensual goes back to Plato. The separation, however, reveals itself as a purely conceptual distance between the two areas over which the metaphorical transference would take place. Such concepts cannot be sustained for a mind that tries to overcome metaphysics. If the heart as the organ of mood is that which actually allows us to see and hear, then the division of being into different sensory regions cannot be maintained - the eye can also hear and the ear can see. Heidegger therefore does not mean this metaphorically:

“What are these pointers, which look like a digression? They want to make us cautious so that we do not prematurely mistake the talk of thinking as hearing and seeing as a mere metaphor and thus take it too lightly. If our human-mortal hearing and seeing do not have their essence in the mere sensual perception, then it is not completely unheard of that audible things can be seen at the same time when the mind looks with hearing and hears with looking. "

There is even nothing , as Heidegger said in “ What is Metaphysics? “ Elaborated, neither seen with the eye nor audible with the ear. For Heidegger it is the basic experience of fear, i.e. a mood that confronts us with nothingness, namely when the world sinks in its significance for us and the meaning offered by the public is not for us.

In so far as Heidegger's mood is about overcoming metaphysical ideas, one can understand from here his rejection of metaphor, which of course depends on metaphysical concepts and the resulting separations. Because only on the basis of the metaphysical separation can the metaphor be understood as a linguistic figure that saves the understanding gained in one region of being by means of its imagery into another region of being. Rather, the world is always a whole, within which there is nothing that we can grasp linguistically in such a way that we can say of it that we know its "real essence" and use this in another way as a metaphor or symbol:

“Looking at it like this, we are tempted to say that the sun and wind appear as“ natural phenomena ”and then“ also ”mean something else; they are "symbols" for us. When we talk and mean like that, we consider it to have been agreed that we know "the" sun and "the" wind "in itself." We believe that earlier people and humanities also got to know "first" "the sun", "the moon" and "the wind" and that they then also used these alleged "natural phenomena" as "images" for some underlying world. As if, conversely, only "the sun" and "the wind" do not appear from a "world" and are only what they are insofar as they are composed from this "world" [...] the "astronomical" sun and the "meteorological" wind, which we think we know today more progressively and better, is no less just more clumsy and leaky, poetry [...] We should [...] note that [...] the doctrine of the "image" in poetry, of the "metaphor", in the area of Holderlin's hymn poetry, not a single door opens and nowhere brings us outside. [...] Even the "things themselves" are always composed before they become "symbols", so to speak. "

However, there are also indications in Heidegger's work that he occasionally does not completely succeed in abandoning visual language:

“In contrast to the word of poetry, the saying of thinking is figureless. And where there seems to be a picture, it is neither the poetry of a poem nor the vividness of a "sense", but only an "emergency anchor" of the daring but unsuccessful lack of images. "

The language criticism and Sigetics of the late Heidegger

Heidegger replaces “logic” (speech / word teaching) with his concept of “sigetics” (silence teaching). This refers to his criticism of traditional conceptions of how language relates to objects: in traditional metaphysical positions these are understood as well-defined objects that are stable over time, objectively given - "present" and "presented" (as stable Entity for itself before the consciousness). Here Heideggers already starts a criticism of Plato and his successors: his concept of ideas presupposes that one refers to objects as "brought to a state" - while Heidegger is concerned with an analysis of those structures that make this objectifying reference possible at all. The stability of metaphysical ordering schemes is understood to be future, for example, compared to the practical and meaningful references and circumstances (Heidegger calls them “world” as a whole) that we associate with “things”. A stable “knowing subject” of the same type of “rational beings in general” with well-definable cognitive faculties and schemes, for example, is again understood to be future-oriented in relation to dynamic structural conditions, including in particular the enabling conditions that Heidegger identified as “temporality” for time positions for oneself and other objects and ascribing permanence. Furthermore, Heidegger differentiates between different modes (“existentials”) to refer to the whole of “world”, criticizes calculating, technical-utility-calculating, objectifying approaches and explains their predominance in terms of time diagnostics. Against this background, he sees attempts at theory of traditional metaphysics as inadmissible narrowing, because they are only oriented towards "existing", imagined, existing objects - "being", and answers every question about the meaning and origin of beings to the effect that they are Describes “being” as a principle cause following the pattern of other beings. In order to make these and other differences in his method, which he at times called “ fundamental ontology ” in contrast to “ontic” modes of description, recognizable, Heidegger speaks of “being” - which means that dynamic, process-like structure that is understood as the origin of beings becomes. This dynamic relation to time is expressed in expressions such as “essence of being”, whereby “essence” is not meant in the sense of a static essence, but is to be read verbally-procedurally: the being “west” (and is not of this essence as a stable one Object can be lifted). Heidegger also speaks of "event" and refers to this. a. also to the temporal constitution depending on its own subjective relation. This origin, “being”, remains misunderstood and misunderstood by traditional metaphysical approaches - instead, philosophy has to think and say a “different beginning”.

Both the theoretical language of philosophy, referring to the naming of already existing things, as well as the everyday language (of whatever culture) are, according to Heidegger, "increasingly widely used and talked to death". “Being” cannot be named using conventional ways of speaking. In particular, the essence of language is not actually described by the logic in the traditional sense, which is based on the propositional sentence, but the essence that establishes and enables it is in turn identified as “Sigetics”. Heidegger therefore sees logic itself as a system of rules created through systematization and abstraction, which, however, is preceded by a linguistically structured world that can never be made explicit and whose richness cannot be obtained through logical description alone.

The rendering of sigetics as a “doctrine of silence” is misleading insofar as Heidegger's question about the meaning of “being” cannot be locked into a rule-based “school subject” - if only “because we do not know the truth of being” (it is only ever “suitable”). Instead, it is about a more original way of speaking compared to statements of facts, which Heidegger simply calls "saying": "Saying does not describe anything that is present, does not tell the past and does not anticipate the future". In general: “We can never say being itself… directly. Because every legend comes from being. ”Every saying is, as it were, already too late - and refers back to its origin, which can only be identified ex negativo as the silence, which preceded this saying and would therefore alone be appropriate to it .

Heidegger is not concerned with mere silence (“keeping quiet”), but with reference (“naming”) to what is actually to be said in “silence”: “The highest thoughtful saying consists in not simply keeping silent about what is actually to be said in saying but to say it in such a way that it is mentioned in non-saying: the saying of thinking is silence. This saying also corresponds to the deepest essence of language, which has its origin in silence. ”Heidegger sees examples in the poetry: Trakl's“ Im Dunkel ”begins with the verse“ The soul is silent in the blue spring ”- Heidegger adds:“ It sings the soul by keeping him silent ”; Heidegger comments on the phrase “ one gender” blocked by Trakl : this “hides the basic tone from which the poem ... the secret is silent ... In the emphasized“ one gender ”hides that unity, that of the gathering blueness of the spiritual night agree. "

The dynamic of silence and telling here follows the structure otherwise described by Heidegger (for example in the origin of the work of art ) as “concealment” and “concealment”. "Silence" is not a mere breaking off of linguistic quality, but means the event of being related to "being" itself: "The basic experience is not the statement ... but the keeping of one's behavior against the hesitant failure in truth ... the need, the necessity the decision arises. ”In formulations like this that are typical of Heidegger's late work, not only is almost every word a specific Heidegger term, whose sense of use requires knowledge of his earlier writings - in addition, Heidegger's late work seeks a dense, almost poetic style. One has spoken of a “style of event-historical thinking” and identified this with sigetics.

Terms

Being and being

- See main article ontological difference .

Fundamental to Heidegger's approach to the problem of being is the distinction between being and being, the ontological difference. With “being”, Heidegger describes - to put it simply - the “horizon of understanding”, on the basis of which only things in the → world , “being”, can encounter. Heidegger takes the point of view that being has not been explicitly discussed up to its present. According to Heidegger, this has led to a confusion between being and being since the classical ontology of antiquity.

However, being is not only the 'horizon of understanding' that is not thematized, but also denotes that which is , thus has an ontological dimension. One could say that Heidegger equates understanding with being, which means: only what is understood is also, and what is is always already understood, since being only appears on the background of being. That something is and what is something always go hand in hand.

According to Heidegger, a central mistake of classical ontology is that it posed the ontological question of being by means of merely ontic beings. Disregarding the ontological difference, she reduced being to beings. With this return, however, it is precisely, according to Heidegger, that it obstructs the being of being. The hammer may serve as an example for this: If one assumes that only beings are in the form of matter, then when asked what a hammer is, the answer is: wood and iron. However, one can never understand that the hammer is “the thing to hammer” after all, because its being only shows itself within a world of meaningful references.

To be there

Heidegger's term for the person he chooses in order to distinguish himself from other disciplines and associated associations. What it is like to be Dasein , i.e. the phenomenological description, is what Heidegger calls → being- in-the-world , what Dasein is, i.e. the ontological determination, he calls → care . The basic structures of existence make up the → existentials .

In Being and Time , the fundamental ontology and the analysis of Dasein connected with it should serve to provide a solid foundation for the ontology. Heidegger later interprets his use of the term “Dasein” in Being and Time as being motivated by the relationship between being and the essence of human beings and the relationship between human beings and the openness of being.

“Dasein therefore has multiple priority over all other beings. The first priority is ontic: this being is determined in its being by existence. The second priority is ontological: Dasein is "ontological" on the basis of its determination of existence in itself. But Dasein also belongs to Dasein - as a constituent of the understanding of existence - an understanding of the being of all non-existential beings. Dasein therefore has the third priority as the ontical-ontological condition of the possibility of all ontologies. Dasein has thus shown itself to be primarily ontologically questioned, above all other beings. "(SuZ GA2, 18)

- Occurrence:

1927 • GA 2, Being and Time brings the comprehensive fundamental analysis of Dasein.

1949 • GA 9, p. 372f: reinterpretation: “Dasein” is said to have already served to formulate being and time to determine the essence of man as belonging to being.

existence

The essence of → Dasein lies in its existence. Heidegger is hereby directed against a conception of man as something that is merely present: man has to lead a life, he is essentially this life. He has to make decisions and realize possibilities or let them go. "Being itself, to which Dasein can relate one way or another and always relate somehow, we call existence." (SZ, GA2 12)

Heidegger later reinterprets his use of the term by interpreting it in such a way that even at the time of being and time it was meant a determination of the essence of human beings, which defines them as being through their relation to being and to → unconcealment .

“Existence is the title for the kind of being of the being that we are ourselves, human existence. A cat does not exist, but lives, a stone does not exist and does not live, but is there. "(Lecture: Metaphysical beginnings of logic in the outcome of Leibniz (summer semester 1928): GA 26, 159)

- Occurrence:

1949 • GA 9, p. 374f: Reinterpretation: Even in being and time, existence is supposed to have meant the openness of man to being.

Existential items

The existential aliens are essential structures of being. The existentials include → being in the world, → being with , → worldliness , → thrownness , → designing , → speaking , → state of mind , → understanding , → fear , → worrying , → worry , → being to death . In the existentials → can disclosedness of his being-ever open-minded self-adhesive when it is not only a land of existence for themselves, so a ontological enforcement, but the possibility of being expressly taken.

“ Existentials are to be sharply separated from the determinations of being of non-existent beings, which we call categories ” (SuZ 44). Categories thus serve the more precise determination of beings that are not Dasein. “Existentials and categories are the two basic possibilities of characters of being. The being that corresponds to them demands a different way of primary questioning: Being is a who (existence) or a what (presence in the broadest sense). "(SuZ 45)

Unity

“The being, the analysis of which is the task, we are each ourselves. The being of this being is always mine. In the being of this being, this itself relates to its being. As a being of this being, it is surrendered to its being. Being is what this being itself is concerned with. ”(SZ, GA2, 41–42)“ Unity as a condition of the possibility of authenticity and inauthenticity belongs to existing existence. Existence exists in one of these modes, or in modal indifference. "(SZ, GA2 53)

Being-in-the-world

→ Dasein is in the manner of being-in-the-world. Here Heidegger means the phenomenological description of what it is like to be existence. To this end, he identifies three structural elements of being-in-the-world: → world , → self , → being-in .

Facticity

"The concept of facticity concludes in itself: the being-in-the-world of an" inner-worldly "being, in such a way that this being can understand itself as being stuck in its" fate "with the being of the being that is within its own World encounters. " (SZ, GA2 56). Instead of the term facticity, Heidegger also uses the term → thrownness

Thrownness

Heidegger describes the inevitability of existence with thrownness: being thrown into the world without being asked. The concept of thrownness denotes the arbitrary, opaque and ignorant nature, the facticity of existence as a constitutive condition of human life. Heidegger also speaks of the (constitutive) fact of having to be there.

Thrownness, however, is not a mere attribute of beings, but together with speech and understanding forms the existential basic structure of beings. Dasein as existence is determined by thrownness and design; it is designed design. Dasein does not have the possibility of a design without presuppositions, but the possibility of a design is already historically given to it through its thrownness. “Thrownness, however, is the kind of being of a being, which is always its own possibilities, in such a way that it understands itself in and out of them (projects itself onto them). [...] But the self is initially and mostly improper, the one-self. Being-in-the-world has always lapsed. The average everydayness of existence can therefore be determined as the decaying, opened up, thrown-designing-being-in-the-world, which in its being with the world and in being with others is about one's own being able to be. "(SuZ § § 39) Thrownness and project are originally determined by speech as the existential essence of language. "The explicitly executed thrown draft, which drafts Dasein in terms of its existence that understands being, keeps what has been drafted in an intelligibility structured through speech."

Being to death

The → existence of → Dasein ends with death. To exist means to seize opportunities and let others fall. Death is the last option. The → state of → fear reveals death as this last possibility and that it is → someone's death, i.e. that death is all about me. In the face of death, existence opens up to a defined decision-making space within which it exists. Only when it consciously accepts it does it exist as a whole. Thus death is not simply a final event, but rather reflects back on the existence of Dasein. The mortality and finiteness of existence determine it already during its life. Heidegger calls this overall structure “being to death”.

fear

Fear is a mood that enables → Dasein to find its way back from the state of decay into its actual → Being-in-the-world . In fear, existence comes to itself, to its → unity . In doing so, → authenticity and inauthenticity become apparent. Dasein offers itself the possibility of the → decision for authenticity.

“Fear thus deprives existence of the possibility of decaying to understand itself from the“ world ”and public affairs. It throws existence back on what it fears, its real being-in-the-world. Fear isolates existence on its own being-in-the-world, which, as an understanding, is essentially projecting on possibilities. "(SuZ, p. 187)

“In existence, fear reveals being to one's own being able to be, that is, being free for the freedom of choosing and grasping oneself. Fear brings existence before it is free for ... (propensio in ...) the authenticity of its being as a possibility that it always is. "(SuZ, p. 188)

“The possibility of excellent development lies in fear alone, because it is isolated. This isolation brings existence back from its decline and reveals authenticity and inauthenticity as possibilities of its being. These basic possibilities of existence, which is always mine, show themselves in the fear as well as in themselves, undisguised by inner-worldly beings, to which Dasein clings initially and for the most part. ”(SuZ, pp. 190–191)

temporality

Temporality is an → existential of → Dasein . It makes the sense of → care . Existence does not exist “in time”, it is temporal . This means that existence is not primarily determined by a time external to it, but rather brings temporality with it as something belonging to it. The measurable time of physics is therefore only a retrospectively externalized and reified form of the original temporality of existence. Only because Dasein is temporal is it determined by the past (Heidegger's term for the past) (it is his past), it can orient itself in the present and → design towards a future . Therefore, in accordance with the definition of Dasein as care, namely as -already-being-in-(the-world) as being-with (beings encountered within the world), temporality is fundamental for the entire care structure: temporality is the meaning of Concern. Temporality is made up of three ecstasies: past, future and present. Heidegger assigns this to the corresponding provision of care:

- Already-being-in-the-world: a past

- To be with (that currently to be worried): present

- To be ahead of oneself (in the draft): future.

Temporality is not something in the world; it comes into being. In doing so, all three ecstasies always come to their own. The assignments to the three moments of concern therefore only represent the primary ecstasy in each case. For example, the past and the present are also important in being ahead of oneself.

In his

Mood , understanding and speech are the three moments of being-in. As the basic types of relation to self and the world, they make up the → accessibility of → existence .

- Sensitivity : The ontological term for the ontic moods. Heidegger would also like to give moods the opportunity to open up the world as it is and not just - as in Kant, for example - leave this task to reason. This corresponds to the phenomenological observation that things in the world obviously concern us, in their unruliness, beauty, unavailability, etc. Central importance is given to the → basic state of → fear .

- Understanding : In Heidegger's work, the term does not only refer to what the philosophical tradition has called reason or understanding. Heidegger's term is much broader and refers to all meaningful references within the world.

- Speech : The ontological term for the concrete ontic language (German, English, French, etc.). For Heidegger, speech is not only a form of communication, but also structures the relationship to the world and to oneself. It does this by uniting all three ecstasies of → temporality , in that it always refers and must refer to the past, present and future at the same time.

Accessibility

The three moments of → being-in , namely being, understanding and speech, make up the opening up of → existence . That Dasein relates to itself and the world in general is the ontological prerequisite for all other concepts of truth, such as that of affirmative statements. Therefore Dasein is always already in the → truth , which Heidegger calls the truth of existence .

However, the → self of existence is primarily determined by the → one , which is why feeling, understanding and speech are initially and mostly → improper , namely as ambiguity , decay and talk . It is only through the call of conscience that existence becomes clear that it can usually be guided by its socio-cultural determinations and that it accepts the public offers of meaning without reflection. The call of conscience modifies the three moments of in-being into fear , design and secrecy . They enable Dasein to → actually be, i.e. In other words, it can now consciously relate to its socio-cultural determinations and the public offerings of meaning and choose which of these it would like to realize within its life context. Heidegger calls this actual development also the determination .

For what defines a person, however, such reflective behavior towards oneself and the world is not enough. Only in the face of death can existence in → being to death be whole. As a last resort, death marks the end of the decision-making space of existence. To exist in the consciousness of death, Heidegger calls running into death, which is why he also calls the resolution conscious of death the resolution running ahead .

dispute

For Heidegger, the dispute is the original togetherness of concealment and revelation in the truth story of the event. Correspondingly, truth is no longer understood in terms of the conditions of presence or correctness, but in those of abandonment or denial. At the same time, the dispute dynamizes the ontological difference , in that it is no longer just a rigid opposition between being and being, but is carried out in the dispute and can thus change. The dispute is necessarily more original than the ontological difference, because no speculative mediation can only create the dispute afterwards. The historical change of being can only be understood through conflict. It is the condition of the history of being.

Shy

See → behavior .

Cautiousness

Behavior is a → basic mood . It is the basic mood belonging to thinking that starts out differently . It is the simultaneous being of two moods: the shyness and the fright . It is the horror of the → abandonment of being , in the experience of nihilism, in which being is only the object of → machination and → experience . Insofar as a changed relation to being is heralded here, at the same time there is a fear of the echoing event in the behavior.

- Occurrence:

1943 • GA 9, p. 307: Shyness is similar to fear.

1936–38 • GA 65, p. 396: Awe of the echoing event.

Basic mood

Because of his mood, man is originally related to the world. According to his → thrownness, it is not something that he could choose, but rather it “attacks him” from his socio-cultural background into which he was born and which he is forced to make his own. The basic mood of → fear is of particular importance in being and time .

If the basic mood in being and time is still a presupposed moment of pre-reflective disclosure, Heidegger later subjects it to an → historical interpretation. The basic mood thus becomes dependent on the throwing of being . This can be seen, for example, in the history of philosophy: the thinker corresponds to the encouragement of being. So every philosophy is based on a basic state of mind in which the thinker lets himself be determined by being. For example, astonishment is the basic mood of the beginnings of philosophy among the Greeks, while Descartes doubt determines the philosophy of modern times.

In the course of overcoming metaphysics, Heidegger tries a → different beginning to thinking. The basic mood associated with this is → behavior .

Question of being

The question of the meaning of being brings Heidegger's main work, Sein und Zeit, on its way. Here Heidegger asks about “ being ”, i.e. what is. If at the same time he asks about its meaning, then this means that the world is not an amorphous mass, but that there are meaningful references in it . For example, there is a relationship between the hammer and the nail. How can we understand this meaningful relationship between both and what is a hammer in this context, how do we determine its being? (So the question is not synonymous with the question of "the meaning of life.")

According to Heidegger, western philosophy has indeed given various answers in its tradition as to what it understands by “being”, but it never posed the question of being in such a way that it inquired about its meaning, that is, it examined the relationships inscribed in being. Heidegger criticizes the previous understanding that being has always been characterized as something that is individual, something that is present. The mere presence, however, does not make it possible to understand references: the determination that something is cannot understand what something is.

In addition, when imagining being as something present, the relation to time is completely disregarded. When determining being as, for example, substance or matter , being is only presented in relation to the present: what is present is present, but without any reference to the past or future. In the course of the investigation, Heidegger would like to show that, on the other hand, time is an essential condition for an understanding of being, since it - to put it simply - represents a horizon of understanding on the basis of which things in the world can first develop meaningful relationships between one another. The hammer, for example, is used to drive nails into boards in order to build a house that offers protection from coming storms. So it can only be in the overall context of a world with temporal relations understand what the hammer out of an existing piece of wood and iron is .

Heidegger would like to correct the failure of the philosophical tradition to bring the meaning of time for the understanding of being into focus with a fundamental ontological investigation. So Heidegger would like to place the ontology on a new foundation in Being and Time .

Heidegger will later turn away from his approach chosen in Being and Time . While there he was still trying to determine a foundation for the ontology with Dasein , later he was concerned with the question of how to understand at all that being has received so many different interpretations in the course of Western history, for example by Plato as an idea , or by Aristotle as a substance. Obviously, this cannot be understood if one only proceeds from existence and the structures that determine it. Instead, Heidegger tries to reflect on being itself, i.e. how it shows itself to people. Heidegger no longer tries to determine being, but to understand how this shows itself in the → event . To this end, he interprets the archives of Western metaphysics, revealing a history of being that to this day essentially determines people and modern technological society.

- Occurrence:

1927 • GA 2, there the introduction.

1949 • GA 9, p. 370: Metaphysics, as imaginary thinking, cannot pose the question of being, moreover it remains integrated into the fate of being.

1949 • GA 9, p. 331: The question of being always remains the question of being, not the question of being in the sense of the truth of being.

Oblivion of being

Forget about being is a term Heidegger uses to describe various aspects of Western metaphysics , science and philosophy . It manifests itself primarily in the fact that the ontological difference is not taken into account, i. H. the difference between being and being.

Abandonment

The term abandonment of being is intended to emphasize in relation to the → forgetfulness of being that it is not a mistake or negligence of man if he does not come into relation to being, but this is due to the way in which being occurs : Man cannot establish truth through this that he applies, for example, transcendental categories to beings, or examines them exclusively with the methods of modern physics, but he relies on being to happen by itself. However, he can keep himself open to the → event . For Heidegger, the abandonment of being is the reason for the “symptom” of being forgotten , which forbids modern people from → living and leads them into → homelessness .

- Occurrence:

1946 • GA 9, p. 339: Forsaken being as the reason for forgetting being, the sign of which is homelessness.

Sigetics

Heidegger had emphasized that one “can never say being itself directly”. In this respect, "Sigetik" takes the place of a " logic " based on statements about beings .

- see the separate article Sigetik

Concern

After the phenomenological determination ( What is the → Dasein ?), Heidegger determines Dasein ontologically ( What is Dasein?) As care. For this he draws on the Cura fable of Hyginus ( Fabulae 220: "Cura cum fluvium transiret ...") as a "pre-ontological test". With this, Heidegger wants to ensure that the determination of existence as a care is not based on abstract principles, but has its foundation in a person's self-experience. For Heidegger, concern is above all concern for the → self and in the form of caring for others. The care can appear in two variants, namely as a stepping-in care, which relieves the other of the care, which however leads to dependence for the other, or it can protrude for the other , so that it helps the other free for his own care to become. Just as → circumspection is part of everyday concern, so is caring for consideration and forbearance . To be with is therefore for the sake of others, worrying for the sake of oneself.

Later on, Heidegger no longer interpreted worry as worrying about oneself or the other, but rather worrying about being. Man takes over the guardianship of being. This is also thought of from an opposition to the → technical mastery of beings, in which Heidegger sees nihilism at work.

- Occurrence:

1946 • GA 9, p. 343: ek-sistence is ek-static living close to being. It is the guardianship, that is, the care for being.

Expired

“Dasein has always fallen away from itself as the actual being able to be and has fallen into the 'world'. The obsession with the 'world' means the dissolving in togetherness, provided this is led by talk, curiosity and ambiguity. "(SuZ, 175)

truth

Heidegger defines truth as "uncovered, ie unconcealedness of beings". (Logic. The question of truth, GA21, p. 6) The following applies: "Sentence is not the place of truth, but truth is the place of the sentence." (GA21, 135) He examines the concept of truth in § 44 from SuZ, which for him is closely linked to being. He equates the “traditional conception of the essence of truth” (SuZ 214) with the correspondence theory of truth (agreement of a judgment with reality). This tried again and again to ignore the finite ways of the temporal and historical existence of → Dasein . For Heidegger, on the other hand, the truth of the statement is based on the fundamental structure of Dasein, i.e. in → being- in-the-world (SuZ 214-219) “The statement is true, means: it discovers what is in itself. It says it "Lets see" (ἀπόφανσις) beings in their discovery. The truthfulness (truth) of the statement must be understood as being discovering. ”(SuZ 218) A statement is true when it shows what is being in its unconcealment. In this way the statement discovers what is. The → disclosure is the most original phenomenon of truth (SuZ 219–223). "The discovery of inner-worldly beings is based on the accessibility of the world." (SuZ 220) Dasein is essentially true, so that it applies: "Dasein is" in truth "." (SuZ 221) Because of the deterioration of Dasein, which is mostly itself in the public of → one loses, the traditional concept of truth is ancestral (not fundamental) (SuZ 223–226). Existence shows itself in the way of appearance. “Dasein is, because it is essentially decaying, according to its constitution of being in the“ untruth ”.” (SuZ 222) Accordingly, “Dasein is equally original in truth and untruth” (SuZ 223). Only the discovery leads to truth. "Truth in the most original sense is the disclosure of existence" (SuZ 223). Finally, Heidegger states that truth is relative to existence, that is, it presupposes existence (Suz 226–230). "Truth 'exists' only if and as long as there is existence." (SuZ 226)

In Heidegger's later philosophy, the concept of truth is determined by the unconcealedness (a-leitheia) of being (Plato's doctrine of truth): “Truth as the correctness of the statement is not possible without truth as the unconcealedness of beings. Because what the statement must be based on in order to be correct, must already be unhidden beforehand. ”(GA 34, 34)“ Originally true, ie unhidden, is precisely not the statement about a being, but the being itself, - one thing, one thing. A being is true, understood in Greek, if it shows itself as that and in what it is. ”(GA 34, 118)“ The meaning of being in the sense of presence is the reason why aletheia (unconcealment) is grinds down to the mere presence (not going away) and accordingly the concealment to mere being away. "(GA 34, 143)

In his contributions to philosophy (1936–1938), Heidegger determined the truth from original thinking as follows: “Thinking is the 'outline of the truth of being in word and concept'” (GA65, p. 21). "But how does the thinker conceal the truth of being, if not in the heavy slowness of the process of his questioning steps and their bound sequence?" (GA65, p. 19). “Because philosophy is such a reflection, it jumps ahead into the most extreme possible decision and, with its opening, masters in advance all the recovery of truth in beings and as beings. Therefore it is sovereign knowledge par excellence, although not absolute knowledge in the manner of the philosophy of German idealism. ”(GA65, p. 44) The thinking remains ambivalent:“ Only where, as in the first beginning, the essence only emerges as a presence , there is soon a distinction between being and its 'essence', which is precisely the essence of being as presence. Here the question of being as such, and that is, of its truth, necessarily remains inexperienced and unfounded. "(GA65, 295)

Finally, Heidegger stated in his letter on humanism (1946): “The essence of the sacred can only be thought from the truth of being. The essence of deity can only be thought of from the essence of the sacred. "(GA9, p. 351)

Essence

Heidegger does not use the term essence in the sense of tradition, i. that is, it does not serve to indicate an unchangeable essence of a thing. Instead, the term refers to indicating from where something has its essence, which is therefore essential for the determination of a thing. So it is not essential for the hammer that its handle is made of wood, but that it is the thing to hammer. Analogously, Heidegger does not determine humans in being and time from a biological point of view (for example as an existing organism), but rather as that being that exists : humans (→ Dasein ) face decisions and possibilities throughout their life, most of which are theirs can seize one and at the same time is guilty of the other. It is this way of life (the "existence") that is characteristic of human beings as human beings . This is why Heidegger says: "The" essence "of Dasein lies in its existence."

Heidegger takes this use of the term to the extreme, particularly in his Hölderlin reading. In Hölderlin's hymn Der Ister, for example, he regards the flow of the Danube as essentially “wandering of the place and place of wandering” and not as the course of physical processes in space and time. The flow could indeed be described physically, but since this can always be done in the same way with every process, this is equally meaningless, i.e. an insignificant description. The task of thinking is therefore - in comparison to natural science - to think about what essentially determines us and things in the world.

- Occurrence:

1927 • GA 2, p. 42: “The" essence "of Dasein lies in its existence.”

1929/30 • GA 29/30, p. 117f: Any thing can be viewed from different points of view. But that does not mean that they are all essential .

1942 • GA 53, pp. 36–59: The nature of the currents is not determined by the modern conception of a physical process in space and time.

World, worldliness

“Worldliness” is an ontological term and means the structure of a constitutive moment of → being- in-the-world . But we know this as the existential determination of → Dasein . Accordingly, worldliness is itself an → existential . ”(SuZ, p. 66) Because existence is worldly, its relation to the world cannot consist in a subject-object relationship . "" "World" is ontologically not a determination of being, which Dasein is not essentially, but a character of Dasein itself. "(SuZ, p. 64)

At hand

Heidegger determines the being of the first encountered inner-worldly being as being at hand. On the other hand, presence is the being of beings, which can be found and determined in an independently discoverable passage through the being that is first encountered. In the third step, the being of the ontic condition of the possibility of discovering inner-worldly beings in general is determined as the → worldliness of the world. (SuZ, p. 88)

frame

Heidegger describes the technical and objectifying thinking as the imaginary thinking in the sense that this thinking brings the being before itself as an object and at the same time conceives it in the temporal mode of the present as existing for it. So man uses technology to present nature as a mere resource. He does this using technical means, the entirety of which Heidegger calls the frame.

criticism

literature

- Hildegaard Feick: Index to Heidegger's "Being and Time" . New edited edition by Susanne Ziegler. Niemeyer Verlag, Tübingen 1991.

- Charles Guignon (Ed.): The Cambridge Companion to Heidegger . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1993.

- Dieter Thomä (ed.): Heidegger manual. Life - work - effect . JB Metzler Verlag, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-476-01804-0 .

- Holger Granz: The Metaphor of Dasein - Dasein der Metaphor. An investigation into Heidegger's metaphors . Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main / Berlin / Bern / Brussels / New York / Oxford / Vienna 2007.

- Michael Inwood (Ed.): A Heidegger Dictionary . Blackwell Publishing, 1999.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Cf. Dirk Mende: "Letter on› Humanism ‹" On the metaphors of the late philosophy of being. In Dieter Thomä (Ed.): Heidegger Handbook . Metzler Verlag, Stuttgart 2003, p. 251.

- ↑ GA 53, p. 428.

- ↑ GA 53, p. 432.

- ↑ See for example Giuseppe Stellardi: Heidegger and Derrida on Philosophy and Metaphor. Imperfect Thought. Prometheus Books UK, New York 2000.

- ↑ GA 9, p. 358.

- ↑ GA 29/30, p. 127f.

- ↑ GA 10, p. 89.

- ↑ Being and Time , GA 2, p. 271.

- ↑ See the study by Byung-Chul Han: Heidegger's Heart. Martin Heidegger's concept of mood. Wilhelm Fink, Munich 1996.

- ↑ GA 10, p. 91.

- ↑ See GA 53, p. 18.

- ↑ GA 10, p. 89.

- ↑ GA 52, p. 39f.

- ↑ GA 13, p. 33.

- ↑ a b GA 65, p. 79.

- ↑ GA 65, p. 79: "The essence of logic is therefore the Sigetics."

- ↑ GA 65, p. 78f.

- ↑ History of Being , p. 29.

- ↑ Nietzsche , Vol. 1, 471f; for the specific meaning of “thinking” in this formulation, s. for example GA 8: What does thinking mean?

- ↑ GA 12, p. 79.

- ↑ GA 26, p. 78.

- ↑ GA 65, 80, emphasis removed

- ↑ For example, Richard Sembera: On the way to evening landing - Heidegger voice path to Georg Trakl . Dissertation Freiburg i. Br., SS 2002 (at F.-W. von Herrmann), p. 51 ff.

- ↑ Martin Michael Thomé: Existence and Responsibility. Studies on the existential ontological foundation of responsibility on the basis of the philosophy of Martin Heidegger, Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg1998, 58ff

- ↑ Heidegger's Philosophy from Being and Time

- ^ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Martin Heidegger

- ^ Friedrich-Wilhelm von Herrmann: Path and method: on the hermeneutical phenomenology of the historical thinking, Klostermann, Frankfurt 1990, 19

- ↑ GA 65, p. 78f

- ↑ GA 65, p. 78

- ↑ GA 65, p. 79

- ^ Critical: Ernst Tugendhat: "Heidegger's Idea of Truth", in: Otto Pöggeler (Ed.): Heidegger. Perspectives on the interpretation of his work, Cologne a. a. 1969, 286-297

- ↑ Heidegger, Martin: From the essence of truth. Regarding Plato's allegory of the cave and Theätet. Edited by Hermann Möhrchen. Frankfurt am Main: 2nd edition Klostermann, Frankfurt 1997 (GA 34).