Hamlet (text story)

This article covers all questions of the textual history of the early prints and the editorial decisions of Shakespeare's drama Hamlet .

Text history

In more recent Shakespeare research, one usually starts from a production sequence that comprises the three steps of writing, performing and printing a work in chronological order. This is based on assumptions about the social conditions of theater productions in the Elizabethan era, above all the observation that many playwrights such as Shakespeare were actors, theater co-owners and employers of an actor's troupe at the same time. Her works served the entertainment needs and pastime of the city population. They usually contained an attractive mixture of music and dance, jokes and clowning, murder and manslaughter, fencing games and state acts. Shakespeare and his contemporary colleagues earned money by performing their plays, the success of which, due to the minimal equipment, was completely dependent on the word backdrop evoked by the text and the skill of the actors . As a result, authors who were also theater owners risked imitating or re-enacting their own productions by the competition by printing their works, which could reduce the proceeds from performance. This situation could be an explanation for the traditional findings of many Shakespeare plays. With the exception of Sir Thomas More, none of Shakespeare's plays has survived as a manuscript. The plays were mainly play texts for the theater. Your manuscripts presumably existed initially in the form of smear versions ( foul paper or rough copy ), from which clean copies ( theater transcript or fair copy ) were made and which then served as a template for a director's book ( playbook or promptbook ). In the case of Hamlet, the history of the text may reflect individual stages in the social framework of the Elizabethan entertainment culture.

Assumptions about the composition and performance before 1603

The time of Hamlet's writing is unknown. All of the assumptions made about this in the literature are assumptions based on circumstantial evidence. The most certain dates are the execution of the 2nd Earl of Essex in February 1601, the entry in the Stationers' Register in July 1602 and the printing of Q1 in 1603. The text of Hamlet must therefore, with some certainty, be between the beginning of 1601 at the latest and the year 1603 should have been completed. The date of the first performance of Hamlet is also not known. Presumably, due to the Stationers entry, it took place in London before July 1602. The first precisely documented performance dates from 1607.

The early prints

There are four early quartos of Shakespeare's Hamlet: a short (presumably unauthorized) version Quarto 1 (Q1) from 1603, a much longer version (Q2) from 1604/05 and two reprints of Q2 with minor variations, obtained from the publisher John Smethwick: one from the year 1611 (Q3) and an undated version (Q4) probably from the year 1622. In 1623 the first folio version (F1) of the collected works of Shakespeare appeared. The Hamlet version in F1 contains additions and cuts based on Q2. The extensions consist of approx. 75 lines of “folio-only” passages, which possibly correspond to “diplomatic censorship” of the manuscript on which Q2 is based. The cuts mostly consist of deleting longer speeches.

Quarto Q1 from 1603

The first four-high edition of Hamlet dates back to 1603. The print presumably dates after May 19, 1603, because on that day the Lord Chamberlain's Men were renamed “King's Men”, which is probably followed by the phrase “his Highnesse seruants “Refers. Two copies of her have survived. The first was discovered by Sir Henry Bunbury in 1823 , soon came into the possession of one of the Dukes of Devonshire and is now in the Huntington Library in California. The English Shakespeare scholar James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps acquired the second copy from a bookseller in Dublin in 1856 and sold it to the British Museum two years later . It is now in the British Library . A third specimen is said to have appeared in the 19th century. The Shakespeare researcher John Payne Collier , known for his forgeries, claimed to be aware of it. This has not been confirmed.

The two quartos are incomplete and complement each other. The Huntington copy (Q1-HN) is missing the title page, while the London copy (Q1-L) is missing the last page. The publisher is indicated: "At London printed for NL and John Trundell". The decorative figure in the middle of the sheet shows that NL stands for Nicholas Ling . The printer could be identified as Valentine Simmes by the decorative figure on the first page of the text . The differences between the two copies are minor, the editors of the new Arden edition found nine variants. The improved errors did not distort the meaning, so "maried" was corrected to "married".

Hamlet's Q1 quarto has been considered a bad quarto since Pollard's 1909 judgment . One would expect the name of Stationer James Roberts to appear on the title page, who wrote the entry in the Stationers' Register on Hamlet on July 26, 1602. It does not, so many authors believe this entry was intended to prevent piracy and the existence of Q1 indicates that this attempt was unsuccessful. There is also no unanimous opinion about the source of Q1. Recent studies support the assumption that Q1 is a transcription from memory (presumably by one of the actors). The authors of the authoritative Textual Companion believe that F1 and Q1 have the same template. Others believe that Q1 was a touring version of Hamlet, and ultimately individual authors combined the various hypotheses and suggested that Q1 was a memorial from the actors performing a simplified version of Hamlet in front of an uneducated provincial audience to have.

Quarto Q2 from 1604/05

James Roberts began printing Q2 in 1604 , of which seven have survived, three from 1604 in libraries in the United States and four from 1605 in England and Poland:

- the Jennens-Howe copy in the Folger Shakespeare Library

- the Kemble Devonshire copy in the Huntington Library

- the Huth copy in the beincke library

- the copy by David Garrick in the British Library

- the copy owned by Edward Capell in Trinity College , Cambridge

- the Gorhambury copy owned by the Earl of Verulam in the Bodleian Library and

- the copy discovered in 1959 in the University Library of Warsaw.

The seven copies of Q2 contain a total of 26 text variants, which only in a few cases require major editorial decisions. A 1955 study by John Russell Brown found that two typesetters worked on the printing of Q2, and a 1989 analysis by W. Craig Ferguson found that two Pica Roman character sets were used in the print. The majority of the errors relate to one of the two typesetters and the character set belonging to it. Most scholars believe that Q2 is based on a handwritten first draft of Shakespeare.

The quartos Q3 and Q4

On November 19, 1607, the publisher John Smethwick acquired the copyright for the Hamlet from Nicholas Ling . He published three reprints of Q2 (Q3-Q5). In 1611 there was Q3, printed by George Eld , and a few years later another reprint (Q4). Both contain some variants compared to Q2. The dating of Q4 is controversial. Jenkins states 1622. Rasmussen has drawn attention to the fact that the printing plate used between 1619 and 1623 on the decorative figure by Smethwick used for title pages shows signs of wear (visible on the angel's curls) and concludes from this that Q4 was printed earlier in 1621. Q3 / 4 were probably used by the typesetters of the First Folio

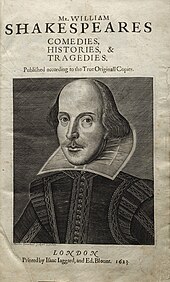

The First Folio 1623

In 1623 an edition of the dramas Shakespeare appeared in one volume, the so-called First Folio. The editors were John Heminges and Henry Condell , the work was published by William Jaggard and Edward Blount . Jaggard's son Isaac took care of the printing in his father's print shop after his death that same year. The volume contains 36 plays by Shakespeare. As of 2018, 234 copies of the “First Folio” (F1) have been preserved. The original print run was probably around 750 copies. At least 5 typesetters were involved in the first folio edition. Newer authors have identified additional typesetters. The Hamlet version in the first folio edition was provided by the typesetter marked B, who is responsible for the largest number of the approx. 400 errors, some of which distort the meaning, in the first folio edition. There are 37 variants of Hamlet's text. So while the problems of text reconstruction are limited in the case of F1, there is considerable uncertainty about the relationship between F1 and Q2. F1 contains approximately 77 lines of F1-only text, which presumably correspond to political (or diplomatic) censorship. In addition, F1 has been significantly shortened compared to Q2, mostly in the case of longer speeches, but is still considerably longer than Q1. There are also numerous variants compared to Q2. F1 contains significantly more capitalization and punctuation marks, at the beginning there are beginnings of a nudes division and more performance notes. F1 is also more consistent in the use of the so-called "speech prefixes", the names of persons that precede a speech. Some writers doubt whether the editors of F1 used the printed version of Q2 for proofreading. Rather, it is assumed that a manuscript was used for this, although it is unclear what kind of manuscript. While the editors of the last Arden edition left the answers to such questions open, other editors have committed themselves to these assumptions. Edwards suspects that the F1 underlying manuscript is a revised copy of the "Theater transcript" ("fair copy") created after 1606. The editors of the RSC edition share this view. On the other hand, the editors of the last Arden series point out that ultimately the exact ratio of Q1 to F1 as well as Q2 is unclear. Q1 clearly contains versions of several passages from F1 that cannot be found in Q2, such as 2.2.337-62 about the theater, 3.2.257 (Hamlets “frightened with false fire?”) Or 5.2.75-80 about Laertes; Numerous Q2 passages that are not in F1 are also missing in Q1 (for example Hamlet's 22 lines about Denmark's reputation or his dialogue with the captain with the subsequent self-talk in 4.4). This certainly allows the conclusion that there is a causal connection between Q1 and F1; however, those Shakespeare scholars who accept such a connection are by no means in agreement on the exact nature of this connection. Many of them conclude that the drafting history of the manuscripts of both Q1, Q2 and F1, which were used as printing templates, deviates from the chronology of the print dates. According to this hypothesis, if the text of Q2 itself formed the template for the print manuscript of F1, contrary to the order of the dating of the prints of Q1 ›Q2› F1, there is a chronological sequence of the creation of the respective manuscripts used as print templates from Q2 ›F1› Q1. Since the date on the title page of the print of Q1 is 1603, this would imply that the original versions of all three texts existed 20 years before the print of F1.

The Hamlet Editions after 1623

In the 17th century, the first folio edition was followed by a total of three reprints in 1632 (F2), 1663 (F3) and 1685 (F4). The text of Hamlet in these three subsequent editions is only a slightly corrected version of F1. After the publication of the First Folio, six other Hamlet quarto editions have survived from the 17th century: in 1637 John Smethwick published another reprint of Q2, which is called Q5. After the London theaters were closed in September 1642 as part of the English Civil War, theater performances were banned for 19 years. In February 1660 the Cockpit Theater was reopened by John Rhodes as part of the restoration of the monarchy. Two new editions of Hamlet soon appeared in 1676, Q6 and Q7. They are known in research as "Players Quartos" because they contain for the first time the list of actors included in today's editions and information on cuts for performances by Sir Wilhelm Davenant's drama troupe. The quartos Q8 from 1683, Q9 (1695) and Q10 (1703) are reprints of Davenant's "Players Quartos". The number of quarto copies preserved is well documented: two copies of Q1 have survived, seven copies of Q2 exist, 19 of Q3, 20 of Q4, 31 of Q5, 33 copies of Q6 / 7, 21 of Q8, 22 from Q9 and 51 from Q10.

The basics of editorial decisions

When editing Shakespeare's works, the editors face different tasks. About half of Shakespeare's plays first appeared in the First Folio of 1623. No quartos from before 1623 have survived. Some of these works, such as “The Tempest”, are in very good lyrical condition. In these cases the following text outputs are practically identical. The other half of the plants present greater challenges. When quartos of different sizes and different quality exist and, as in the case of Hamlet, the folio edition is still faulty, the editors have to decide which text to follow. The result can then be significantly different editions of the work. As the editors of the last Arden edition showed, the editorial decisions are not empirically guided (we take the best-preserved text), but follow production hypotheses of the works and are subject to the assumption that there is an ideal text, “like him was intended by the author ”. The corrections made by the editors are then to be seen as attempts to restore this ideal text.

Manuscript hypotheses

As already explained in the section “Text History”, it is assumed that at least three successive production steps are involved in theater practice in the Elizabethan era: writing, performing and printing a work. Usually, the printing was not done before the performance. The performance and reading versions of a piece could be quite different. Some editors now argue that the stage version of a piece is a "degenerate" text version. The basis of these considerations are manuscript hypotheses. It is assumed that Shakespeare wrote a handwritten rough draft, the so-called " foul paper ". From this foul paper (sometimes also called “rough copy”) a clean copy is then made, the “theater transcript” (sometimes also called “fair copy”). A “playbook” is then produced from the theater transcript. The playbook (sometimes also called “prompt book”, in German called prompting book, although in Shakespeare's time very probably not prompting) contained all the necessary instructions for a performance and the actors' copies were copied from it. So, according to these considerations, there are three manuscript versions of a piece: foul paper, fair copy and the prompt book with the actors' copies. Most editors now believe that in the case of Hamlet the Quarto Q2 of 1604/05 is based on Shakespeare's foul paper, that the source of F1 is a (possibly revised) “theater transcript” and for Q1 the same “theater transcript” as for F1 was used, only that it was shortened more for performance purposes (perhaps in the form of a "prompt book").

Lore theories

While the manuscript hypotheses apply in principle to all Shakespeare plays (and analogously to other Elizabethan authors), the type and number of prints preserved influences the tradition theory advocated by the editors. Almost all Shakespeare scholars share a common tradition of Hamlet:

- Q1 uses a promptbook;

- Q2 uses the foul paper and Q1;

- F1 uses a revised theater transcript and Q2.

The different editions come about because the editors attribute different degrees of authority to the three types of manuscript. The traditional view is that the foul paper has a high authority because it comes from Shakespeare himself. In contrast, the promptbook has little authority because it is the result of compromises between the author and the theater troupe and is adapted to their contingent needs. Only the authority of the theater transcript is disputed. The editors, who choose Q2 as the basis for their edition and who subsequently consult F1, are convinced that only the foul paper is a "holograph", a handwritten manuscript by the author. The editors, who choose F1 as the basis for their edition and who subsequently consult Q2, are convinced that the “theater transcript” is also a holograph , ie it was written by Shakespeare himself.

Edition alternatives

Almost all Hamlet editions can be differentiated according to whether they consider the (hypothetical) theater transcript to be a holograph or not. Accordingly, F1 or Q2 are chosen as the text basis. If Shakespeare wrote the theater transcript himself (there are two lost holographs of Hamlet), then it has a higher authority than the foul paper, since it was written later and is, in a sense, a corrected version of the earlier manuscripts. This assumption represented GR Hibbard in The Oxford Shakespeare. from 1987 and the editors of the Oxford Shakespeare Complete Edition from 1986 with the F1-based editions. The authors, who are convinced that the “theater transcript” is from a third party and that there is only one lost holograph, create Q2-based editions instead. This is what John Dover Wilson did in the case of The New Cambridge Shakespeare. from 1934, TJB Spencer New Penguin Shakespeare. from 1980, Harold Jenkins in the case of the Arden² edition from 1982 and Phillip Edwards in the case of the second edition of The New Cambridge Shakespeare. of 1985. As already shown above, Thompson and Taylor, the editors of the third series of Arden-Shakespeare, consider the problem of text transmission in the current state of research to be unclear due to contradicting or ambiguous evidence and evidence and have therefore decided to in to publish the text versions of Q1, Q2 and F1 separately from each other in a two-volume edition.

Text output

- Charlton Hinman, Peter WM Blayney (Ed.): The Norton Facsimile. The First Folio of Shakespeare. Based on the Folios in the Folger Library Collection. 2nd edition, WW Norton, New York 1996, ISBN 0-393-03985-4

- Harold Jenkins (Ed.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Second series. London 1982.

- Philip Edwards (Ed.). Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge 1985, 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-53252-5 .

- Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006, ISBN 978-1-904271-33-8 .

- Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Texts of 1603 and 1623. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 2, London 2006, ISBN 1-904271-80-4 .

- Jonathan Bate, Eric Rasmussen. (Ed.): Hamlet. The RSC Shakespeare. Houndmills 2008, ISBN 978-0-230-21787-4 .

- George Richard Hibbard (Ed.): Hamlet. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987, 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-953581-1 .

literature

- Michael Dobson, Stanley Wells (Eds.): The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001.

- Ulrich Suerbaum : The Shakespeare Guide. Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 978-3-15-017663-4 .

- Stanley Wells, Gary Taylor: William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford University Press, Oxford 1987.

supporting documents

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 44.

- ^ Ulrich Suerbaum: Shakespeare's dramas. Basel 2001. pp. 23-68.

- ↑ cf. Jakob I's patent to Fletcher and Shakespeare: […] aswell for the recreation of our lovinge subjects […] . see: Chambers: Elisabethan Stage. Vol 2 p. 208

- ^ Ulrich Suerbaum: Shakespeare's dramas. Basel 2001. p. 41

- ^ Ulrich Suerbaum: Shakespeare's dramas. Basel 2001. p. 302.

- ^ Ulrich Suerbaum: Shakespeare's dramas. Basel 2001. p. 301.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 484.

- ^ William Shakespeare: Hamlet. Edited by GR Hibbard. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press 1987. Reissued as an Oxford World's Classic Paperback 2008. p. 69.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. pp. 474f.

- ^ William Shakespeare: Hamlet. Edited by GR Hibbard. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press 1987. Reissued as an Oxford World's Classic Paperback 2008. p. 67.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 523.

- ^ AW Pollard: Shakespeare's Folios and Quartos: A Study in the Bibliography of Shakespeares Plays 1594-1685. (1909). Pages 64-80.

- ↑ Laurie E. Maguire: Sakespearean suspect text: The "Bad quartos" and Their Context. Cambridge 1996. p. 325.

- ^ Wells Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor: William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford 1987. p. 398.

- ↑ Hamlet Weiner. S. 48. Robert E. Burkhart: Shakespeare's Bad Quartos: Deliberate Abridgements Designed for Performance by a Reduced Cast. 1973. p. 23

- ↑ Kathleen O. Irace: Reforming the bathroom quartos. Performance and Provenance of Six Shakespeare First Editions. Newark 1994. pp. 19f.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 478.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 480.

- ^ William Shakespeare: Hamlet. The Texts of 1603 and 1623 .. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Edited by Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor. Volume two. London 2006: p. 17f.

- ↑ Eric Rasmussen: The Date of Q4 Hamlet. Bibliographical Society of America 95 (March 2001) 21-29.

- ^ Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor: William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. Oxford 1987. pp. 396f.

- ↑ Eric Rasmussen: The Shakespeare Thefts - in Search of the First Folios. Palgrave MacMillan, New York 2011, pg. xi. Copy No. 233. Copy No. 234.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 483. The First Folio of Shakespeare. , Norton Facsimile, ed. Charlton Hinman, (New York 1968, 1996). Charlton Hinman. The Printing and Proof-Reading of the First Folio of Shakespeare. 2 vols. (Oxford 1963).

- ↑ Hinman, Printing. Vol 2 p. 511.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 482

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 483.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 465.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 484.

- ↑ Philip Edwards (Ed.). Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge 1985, 2003. p. 31.

- ↑ Jonathan Bate, Eric Rasmussen. (Ed.): Hamlet. The RSC Shakespeare. Houndmills 2008. p. 25.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Texts of 1603 and 1623. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 2, London 2006, ISBN 1-904271-80-4 , pp. 8f.

- ^ Henrietta C. Bartlett and Alfred W. Pollard: A Census of Shakespeares Plays in Quarto 1594-1704. New York 1939. Quoted from Thompson. Arden 3, p. 485.

- ↑ Philip Edwards (Ed.). Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge 1985, 2003. p. 32.

- ↑ Michael Dobson, Stanley Wells (Ed.): The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001. p. 151.

- ↑ Michael Dobson, Stanley Wells (Ed.): The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2001. p. 347.

- ↑ Philip Edwards (Ed.). Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge 1985, 2003. p. 30. Jonathan Bate, Eric Rasmussen. (Ed.): Hamlet. The RSC Shakespeare. Houndmills 2008. p. 25. Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 480. William Shakespeare: Hamlet. Edited by GR Hibbard. The Oxford Shakespeare. Oxford University Press 1987. Reissued as an Oxford World's Classic Paperback 2008. pp. 89f.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 502. Philip Edwards (Ed.). Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge 1985, 2003. pp.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 502.

- ↑ Philip Edwards (Ed.). Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. New Cambridge Shakespeare. Cambridge 1985, 2003. pp. 31f.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 502.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 504.

- ↑ Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (Eds.): Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 1, London 2006. p. 503.

- ↑ See the explanations in Ann Thompson, Neil Taylor (ed.): Hamlet. The Texts of 1603 and 1623. The Arden Shakespeare. Third Series. Volume 2, London 2006, ISBN 1-904271-80-4 , pp. 8-12. While the first volume of the edition contains the annotated Q2 version, the text versions of 1603 (Q1) and 1623 (F1) are also printed in serial order in volume two of the edition. With regard to changes , Thompson and Taylor assume that if there are variants in the other two printed texts, F1 is probably more authoritative than Q2 for changes to Q1; if you leave Q2 you see a higher authoritative power in F1 than in Q1 and if you leave F1 you see Q2 as being more likely to be authoritative (see ibid., p. 11 f.)