Hansken (elephant)

Hansken (* 1630; † 1655) was a cow elephant who was led around Europe as a so-called "learned" lady in the 17th century and showed her tricks. Hansken probably died in Florence on November 9, 1655 .

Origin and life

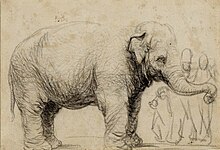

Hansken was born in Ceylon in 1630 and was brought to Holland from there in 1637; the name is explained as a diminutive of the Malayam word ana for elephant (see also the article about the elephant Hanno ). But the little boy was probably a lady elephant. Rembrandt van Rijn saw the animal in Amsterdam in 1637 and made four chalk drawings of it on one sheet, which made Hansken go down in art history; in 1638 it accompanied the biblical fall of man in the background of a famous Rembrandt etching .

Hansken was initially sent on a tour of Dutch and German fairs; her journey can be traced from the sources: appearances in 1638 in Hamburg, 1640 in Bremen, 1641 in Rotterdam, 1646 and 1647 in Frankfurt and 1650 in Lüneburg. If doubts can possibly also be reported to one or the other source that it was really a question of Hansken, their appearance between 1649 and 1651 in Leipzig is documented, among other things, by a preserved notice sheet, the Hansken with its small tusks - typical for Ceylon elephants - depicts and names their Dutch origin.

In July 1651, according to other sources, Hansken was taken from Amsterdam via Bregenz and St. Gallen to Zurich and Solothurn; It is assumed that the journey continued to Rome, because a 25-year-old female elephant is reported here in 1655. A Roman observer noted in his diary that this female was pregnant; It is assumed that this could have been an advertising trick by its owner, as no source mentions the encounter with a bull elephant required for this.

A drawing by the Florentine artist Stefano della Bella shows an elephant carcass with small tusks; on the sheet is noted: "elefante morto in Firenze on 9 di novembre 1655".

The learned elephant

The scholars of the 17th century, if one follows the sources, allowed themselves to be carried away to quite fantastic assumptions about the abilities of the elephant, possibly because of its impressive size. In ancient times, it was believed, he was considered the “darling of the gods”; Pliny had been certain that the elephant could be trained to write Greek letters. There was also talk of fearful dreams, as well as his "mildness and meekness"; whoever rode it would have "the stomach ache, as if one were on the sea, so a bit impetuous".

However, it seems that the scholars never talked about the real abilities of these creatures, which they were able to display at the fairs in the 17th century. Hansken's panels show that the pachyderm lady waved the flag and fired a pistol; she could put the hat on and take it off and, following the contemporary leaves, even wield the sword with a certain elegance. In Frankfurt, according to a source, the animal beat the drum, blew the trumpet and "made its due respect with a scratching foot, even politely" to the amazement and amusement of the audience.

Hansken's success was based in particular on her charm for the "oculi vulgi", which - according to Stephan Oettermann in 1982 - "the mob's speechless gawking". For the scholars, however, the image of the animal “was composed of a hopeless hodgepodge (for modern eyes) of learned inconsistencies. Only very gradually does the outline of the elephant we know today begin to emerge from amid the tangle of allegorical exaggerations, fables and stories of wondrous virtues and qualities. "

reception

Hansken was not the first elephant to be led around the markets of Europe. Between 1629 and 1631 an elephant appeared between Nuremberg and Rome , which is the first fairground elephant in Europe and which both inspired Caspar Horn's representation of Elephas from 1629 and became the model for Gian Lorenzo Bernini's obelisk bearer in Rome.

Hansken's appearances provided the opportunity to bring Caspar Horn's remarks about the nature of the elephant closer to the audience, for example in a text that was created in 1650 on the occasion of the elephant shows in Saxony. The sources for Hansken's journey were published in 1982 in a study on The Pleasure of the Elephant. An Elephantographia Curiosa compiled for the first time.

In 2013, a team of researchers found that the elephant skeleton in the La Specola Museum in Florence was Hansken's skeleton.

literature

- Stephan Oettermann : The elephant curiosity. An Elephantographia Curiosa . Syndikat, Frankfurt am Main 1982. pp. 44ff. and pp. 124-129. ISBN 3-8108-0203-4

- Leonard J. Slatkes: Rembrandt's elephant . In: Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art , Volume 11, No. 1, 1980

Web links

- Own description of the great and wonderful elephant which in this year 1650 (...) was brought to the world-famous trading city of Leipzig, then to the (...) city of Dreßden by a Dutchman , Göttingen digitized

- elephanthansken.com

Remarks

- ^ The British Museum ( Memento of April 4, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ in the following referenced from Oettermann pp. 124–129

- ↑ Annales Hamburgienses I (1638). n. E. Finder: Hamburg bourgeoisie . Hamburg 1930, p. 372f

- ^ Koster, Chronicle of Bremen . n. F. Peters, Freimarkt in Bremen. History of a fair . Bremen 1962, p. 83

- ^ John Evelyn, Diary (August 13, 1641); ed. by. ES de Beer, Oxford 1955, I p. 39-40

- ^ AA Lersner The far-famous Freyen imperial election and trading town Franckfurt on Mayn Chronica . 1706-1734, 2 Vols. I / 1, Cap. 27, p. 431

- ↑ Johannes Peisker: Excerpt from a letter from Johannes Peisker in the service of Johann Maximilian to the boy in Frankfurt a. M. to Jubker Daniel zum Junge… communicated by Dr. Bauer ... In: Communications to the members of the Association for History and Archeology in Frankfurt am Main 5 (1874–1879), pp. 253–256; Letter of April 27, 1647, p. 254

- ↑ Torquato Tasso: The noble householder, Germanized by J. Rist . Lüneburg 1650, p. 84

- ↑ Fig. In: Oettermann (1982) p. 127

- ↑ Bartholome Bischoffsberger : Appenzeller Chronik , St. Gallen 1682, p. 534

- ↑ F. Haffner: Kleyner Solothurnischer Schaw Square historical world stories Zweyter Theil: strange Instead Chronology . Solothurn 1666 n. P. Th. A. Bruhin: Zoological things from the Solothurn Chronicle . In: Zoologischer Garten 8 (1867), pp. 61-67

- ^ Fabio Giglio: Diario (1655) n. William S. Heckscher: Bernini's Elephant and Obelisk . In: Art Bulletin 29 (1949), pp. 155–182, fig.

- ↑ in the following referenced from Oettermann p. 43 ff.

- ↑ Caspar Horn: Elephas. This is historical and philosophical discourse / of the great miracle animal, the elephant / whose wonderful nature and eyesight; the like of those who had been killed in Germany for a long time and seen by many thousands of people. Outside of reinforced old and new histories, compiled and written by Caspar Hornium Phil & Med Doctorem . Nuremberg: Simon Walsmeyer 1629, p. 95

- ↑ after: Julius Caesar Scaliger: De Elephante . In: JCS, Exotericarum Exercitationum liber quintus decimus de Subtilitate ad. H. Cardanum . 1557, exerc 204; that. Frankfurt / M. 1576; 1592; 1612; Hanover 1620; Frankfurt / M. 1665

- ↑ Horn (1629), p. 59

- ↑ Horn (1629), p. 71

- ↑ Peisker (1647), p. 254 s. O.

- ↑ Oettermann (1982) p. 46

- ↑ Own description / Of the great and wonderful elephant / Which in this year 1650. In our Meißner Land, first in the world-famous trading city of Leipzig, then in the Churf. Saxon resident city of Dreßden by a Dutchman has been brought […] Printed in 1650

- ↑ Elephant skeleton, Florence

- ↑ Roslin team helps solve elephant riddle , The University of Edinburgh , November 15, 2013 (accessed April 3, 2015)