Hanno (elephant)

Hanno (around 1510; † June 8, 1516; Italian Annone ) was an Indian elephant that King Emanuel I of Portugal (1469–1521), known as Manuel the Happy , gave to the newly elected Pope Leo X as a gift. He came to Rome in 1514 and became the Pope's favorite animal. Hanno died as a result of constipation and her treatment with a gold-enriched laxative.

background

Elephants had come to Europe as diplomatic gifts or tributes since around 800, sent by oriental rulers, Indian princes or vassals from North Africa. Charlemagne had received one , and the Emperor Frederick II is also told that he owned one ; Louis the Saint brought a pachyderm with him to France after a crusade . Since the early modern times, the large animal, a living and spectacular treasure, has been a popular prop for effectively staging the politics of European rulers. For example, the journey of the future emperor Maximilian II with the elephant Soliman from Spain to Vienna in 1551/52 went down in the history of diplomacy. Louis XIV of France kept a rare African specimen in the enclosure at Versailles for 13 years . As a kind of "living coin for buying sympathy", however, the animal was unsuitable in the long term; it often survived neither the unfamiliar climate nor the stress of representative missions. In particular, the “circulation of giving away” in Europe was a problem for the animals.

The Portuguese colonies that arose after the discovery of the eastern sea route to India in 1498 and their development, mainly through the trade in spices , encouraged Manuel I to surround himself with state elephants like a maharajah in his residence near Lisbon. It is reported that he always had at least five elephants accompany him to the cathedral. When the newly elected Pope had to be given a present according to the ruling custom, Manuel I fulfilled this duty with a pachyderm: an elephant named Hanno.

origin

Alfonso de Albuquerque , Governor of India, had sent two elephants to Lisbon from Cochin in 1511 ; one of the animals was a gift from the King of Cochin to Manuel I, the second Albuquerque had bought himself. In 1513 he acquired two more elephants, which he also sent to his king, on two different ships, so that at least one could get to its destination alive. Later notes from Rome, which identify Hanno as a young animal, suggest that he was one of the two pachyderms shipped as early as 1511, one of which was demonstrably still young; However, it cannot be determined whether he was the animal given or bought. The animals were housed in the menagerie of the royal Ribeira Palace in Lisbon ; one of them was being prepared for a new, long journey.

Hanno's trip to Rome

Manuel I put together a delegation of seventy dignitaries who, under the direction of Tristão da Cunha, were to bring a shipload of valuable gifts along with 43 rare wild animals from Manuel's possession to Rome in 1514. The effort of this diplomatic enterprise, of which an elephant was to lead the entry of the train into Rome, was due to the special role that the Pope had played since the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) with regard to the delimitation of the Spanish and Portuguese overseas Possessions. In order to maintain the new, extremely lucrative spice trade against the Spaniards, King Manuel wanted to secure the favor of the new Pope.

It took many weeks to prepare for the trip, and the cargo in particular caught the attention of Lisbon residents. The transport of the apparently nervous elephant from the Ribeira enclosure to the ship, which was not that easy, became legendary and brought all kinds of stories into circulation; his departure became a popular festival.

The excellently prepared voyage in 1514 with an elephant on board from Lisbon to the Italian coast went smoothly. The journey in the ports was stormy, as the curiosity of the population about the strangers with the giant creature made the necessary stops difficult. The elephant then became a sensation on its way across the country. In an inn in Corneto where the legation had found accommodation, a crowd of people who wanted to take a look at the elephant brought down the roof of the inn.

In the following, the delegation's journey with its entourage turned out to be increasingly difficult; caravans of curious people mean the logistics of the trip got out of control. The decision to stick to the schedule despite the wishes of cities and nobles to stay with the animal with them, evidently increased the vehemence of the curiosity; Devastation remained. When the first country houses outside Rome suffered damage, Pope Leo X sent a company of archers from his Swiss Guard , which in turn increased the curiosity of the Roman celebrities, who now hurried to meet the entourage. Hanno's accommodation at the gates of Rome in preparation for his triumphal entry into the city resembled a fortress.

Nevertheless, on March 19, 1514, the delegation led by da Cunhas succeeded in moving the elephant, loaded with a castle-like structure, with his gigantic train into Rome in a pompous triumphal procession and, with exemplary observance of the ceremonial, the gifts and the menagerie to the Pope to hand over. The elephant is said to have given the Pope the greatest joy.

The news of the successful diplomatic mission prompted Manuel of Portugal a year later, in 1515, to pass on to Rome a rhinoceros that had been sent to him from Albuquerque to Lisbon, but which never arrived there alive and was immortalized by Albrecht Dürer .

Hanno in Rome

Hanno got his name Annone , German: Hanno , in Rome and immediately became Pope Leo X's favorite animal. Hanno-Annone got his own building in the Vatican Gardens . His supervisor was Giovanni Battista Branconio dell'Aquila , chamberlain of the Pope and a friend of Raphael , who is said to have made a drawing of Hanno, which has not survived; two similar drawings are considered copies of them. Four studies based on the living animal were long attributed to Raphael, but are now considered works by Giulio Romano . These drawings were also copied and served as templates for numerous paintings, frescoes and illustrations, such as the copper engraving The Battle of Zama shows, which Cornelis Cort made in 1567 after a painting by Romanos. A fresco on the ceiling of the Loggia di Raffaello in the Apostolic Palace of the Vatican depicting the creation of animals and an elephant in the background was created around 1515/17 and is attributed to Giovanni da Udine ; Raffael is said to have supplied the design.

Hanno and the Pope

The keeping of exotic wild animals in menageries was not uncommon in the European rulers. Pope Leo X was also used to having rare animals around him; his father Lorenzo il Magnifico had a famous enclosure in Florence and studied wild animals in detail. Leo's facility in the Vatican immediately included a small zoo, in which, in addition to a bear and two trained leopards, he already kept a sensational animal: a small chameleon .

Not only the Pope was delighted with Hanno, but also the people. The Pope organized occasional public performances of the elephant, who, at the request of the mahout , his Indian caretaker and instructor, bowed and kneeled, sprayed water around him, danced to music and evidently performed all sorts of tricks.

The fact that the Pope was particularly fond of his pachyderms is expressed in the tradition of spectators who saw the Pope play with Hanno on the Sunday on which the population was allowed to visit the enclosure and who noticed the devoted clumsiness of the plump man. When Lorenzo di Piero de 'Medici , nephew of the Pope, wanted to borrow Hanno for an event in Florence as early as 1514, his uncle refused because he feared that Hanno's health might be damaged on the long journey. Leo announced in his refusal that he was worried about Hanno's feet; Although he had thought about the construction of footwear, the animal would not be able to cover the distance in the time in question, even in shoes.

There is evidence of a triumphal procession for the poet and court jester Baraballo. Giacomo (or Jacopo) Baraballo, Abbot of Gaeta, was one of the more prominent figures in the mixed society that populated the apostolic court of Leo. His artfully improvised verses, based on the model of Francesco Petrarch , are said to have caused the Pope and his guests to regularly outbursts of great amusement in their involuntary comedy, and to general amusement he was showered with honors to which he is said to have been very receptive . Since he considered himself to be Petrarch's equal and had come to Rome specifically to be crowned poeta laureatus , the Pope used the opportunity for a special display of cruel humor and crowned him on September 27, 1514 in a selected ceremony that took place in many details have been handed down. The high point was showing him around Hanno, which the elephant initially endured patiently. The spectators attracted by the spectacle, however, made such a noise that the elephant became nervous and shook off the poet prince; the event found its literary expression and therefore remained unforgettable. Later sources testify that Baraballo, apparently no longer in full possession of his spiritual powers, died shortly afterwards.

When Hannos was deployed again, there was a serious accident. Giuliano de 'Medici had Filiberta of Savoy on January 25, 1515, the sister of the late King Louis XII. of France, married and was expected in Rome with his wife in March. At his reception not only was his path decorated with triumphal arches, but also a huge entourage of nobles and Hanno, packed with a tower in which armed men sat. The gun salute and the roar of the crowd panicked the elephant, he tried to turn around, the tower falling towards the Tiber; Pushing people got under horse's hooves and there were injuries. An official report named thirteen dead.

Hanno's end

In 1516, Leo's brother Giuliano died unexpectedly ; Leo himself had a fever and a fistula plagued him. A heretical monk predicted their imminent death for him and his animal. At the beginning of June Hanno fell seriously ill; he could barely breathe and had cramps. Pope Leo called his own doctors who diagnosed angina because of the shortness of breath . The animal also suffered from constipation, and the doctors decided to treat it with a laxative which, according to standard practice, they fortified with a large amount of gold and given the elephant in a high dose given its size. The therapy was ineffective and increased the pressure on the digestive system; the animal died on June 8, 1516.

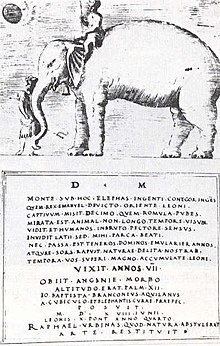

The Pope had his stable-master Branconio produce for him an epitaph with an inscription by Filippo Beroaldo , which names angina as the cause of Hanno's death; the memorial plaque, once attached to the outside of the Vatican wall, has not been preserved and is only attested in a drawing. That the Pope could also have publicly expressed his grief over the death of the beast suggests derisive pamphlets circulating in Rome, but also later in the Protestant north, for example a "testament" of Hannos, allegedly by Aretino , or Luther's comments on the Pope's love of elephants.

Hanno's afterlife

Since his arrival in Rome there have been repeated reports about Hanno; handwritten documents, also from Albuquerque, attest to its origin. Hanno created legends that earned him the curiosity of research and scientific reception .

Legends

Even Hanno's naming, comparable to that of the elephant Hansken , is unclear. One suspected Carthaginian origins as well as the corruption of the Malabar term "ana" for elephant.

Several stories soon began to circulate about the difficulties of getting Hanno aboard a ship in Lisbon. At first Hanno did not want to board the ship when he was loaded in Lisbon. In order not to have to leave his beloved, his Indian guard described Rome to him in the darkest colors. Under threat of the death penalty, he then painted Hanno wonderfully the future, whereupon Hanno dutifully followed all orders and behaved extremely peacefully on the trip. In another version Hanno was promised to become head of Christianity and failure to keep the promise later led to his death. Doubts that there were any problems with Hanno are justified.

Assumptions that Hanno competed against a rhinoceros in Lisbon or that he was caught in a storm during a ship voyage that drowned the rhinoceros are probably due to an incorrect dating in the inscription of the famous Dürer woodcut from 1515, which crossed the national borders circulated out. When he went ashore during the voyage, Hanno not only caused crowds, but also often left his accommodations in danger of collapsing; the descriptions of Hanno's sensational trip overland to Rome, however, sometimes cannot decide who caused the houses to collapse, when and where.

Hanno's docility and the affection of a Pope who filled his office with a luxurious lifestyle also lifted the perception. When Hanno finally reached the Pope, it was said that he had accomplished the feat of kneeling down three times in front of him, which had not been thought possible, since it was believed to be inferred from ancient writings that elephants had no knee joints. In addition, Hanno had independently sucked water from a bucket with his trunk and splashed the clergy present with it, which was extremely delightful for Leo X. The stories of Baraballo, the court jester of Leo X, were mixed up with the accident on the occasion of the visit of Giulianos de 'Medici; It was reported that on the solemn occasion of Baraballo's coronation as Poeta laureatus he was allowed to ride on Hanno and Hanno threw the event by going through - on purpose, as some believed - and the proud poet in the to the great delight of the audience Tiber thrown off.

Different versions of Hanno's end have come down to us. The "angina" noted on the epitaph suggests that Leo's doctors apparently were unable to identify a connection between Hanno's shortness of breath and severe constipation. Rumors circulating in Rome after Hanno's death suspected the humid air of Rome as the cause of Hanno's sudden death, or assumed that the ambitious equerry Branconio had a lack of care; The suspicion of malnutrition, probably the real cause of Hanno's illness, was also expressed. Another source spread that Hanno had been gilded on the occasion of a triumphal procession and died.

reception

In the traditions, including the contemporary ones, Hanno is sometimes referred to as a white elephant . Since there was no comparison for this variety of nature in Europe in the 16th century, it is assumed that it must at least have been light in color. White elephants received special treatment throughout their lifetime in India and Ceylon. The sources attesting to Hanno's origin allow the conclusion that it was probably an already trained young elephant, which undoubtedly increased the value of the gift; There is no evidence of the animal's special status as a white one.

The stories surrounding Hanno and his presence in sources, drawings and paintings have preserved him over time. Since the 1980s there have been two studies on the Pope's elephant based on modern source research: Stephan Oettermann , Die Schaulust am Elefanten. Eine Elephantographia Curiosa (1982, pp. 104-109) and Silvio A. Bedini: Der Elefant des Pope (1997/2006).

Bedini also devoted himself extensively to the question of the whereabouts of the carcass. In 1962, during construction work on the grounds of the Apostolic Library of the Vatican, bones and a large tooth were found, which had been classified as fossils of an elephas antiquas and housed in the collections of the Vatican Museums . A new investigation initiated by Bedini in the 1990s after exploring the site and the background to the find came to the conclusion that the bones and teeth are by no means fossilized, but the relics of a young elephant. Two ornamented tusks that were previously unnoticed in the Sala of the Archivo Capitolare of St. Peter's Basilica had hung were now also examined; it was found that they had been taken from a dead animal. As a result, the reasonable assumption could be made that the bones, the tusks and the large tooth could be the remains of Hanno.

literature

- Silvio A. Bedini: The Pope's Elephant . Carcanet, Manchester 1997, ISBN 1-85754-277-0 ( Ger . The Pope's elephant . Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-608-94025-1 , review )

- Donald F. Lach: Elephants . In: Ders .: Asia in the Making of Europe. Vol. 2. A century of wonder. Book 1. The Visual Arts . University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1970, ISBN 0-226-46750-3 , pp. 123-158

- Stephan Oettermann : The elephant curiosity. An Elephantographia Curiosa . Syndikat, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-8108-0203-4 , pp. 31, 97ff., 104-109

- Mathias Winner: Raffael paints an elephant . In: Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz 9, 1964, Part 2–3, pp. 71–109

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Oettermann: Die Schaulust am Elefanten , p. 31.

- ^ G. de Brito: Os pachidermes do estado d'el rei D. Manuel . In: Revisto de educação e ensino 9, 1894, quoted in in Oettermann: Die Schaulust am Elefanten , p. 105 after Lach: Elephants , 1970.

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , pp. 60, 66.

- ↑ Bedini: Der Elefant des Pope , pp. 41–43; Pp. 46-52.

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , provides in the chapter The Road to Rome (pp. 53-78) a detailed description of the journey and the entry of the delegation in Rome, based on contemporary sources; see. also the quotation in Oettermann: Die Schaulust am Elefanten , p. 107 from LA Rebello da Silva: Corpo diplomatico Portuguez , Lisbon 1862; I, p. 236.

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , reproduces excerpts from this extensive work (pp. 191–192) and illuminates its meaning.

- ↑ cf. Winner: Raffael paints an elephant , and Bedini: The Pope's Elephant .

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 202

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 107f.

- ^ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 111; Apparently, this elephant was a "trained" one, which, because it was young, made it a particularly valuable gift to Manuel I at the time.

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 101.

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 111f .; Leo's letter to his nephew, reproduced there in a detailed summary, is a prime example of refusal diplomacy.

- ^ Source at Winner: Raffael paints an elephant , p. 87; quoted in Oettermann: Die Schaulust am Elefanten , p. 108; Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 115ff.

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 115.

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , pp. 118–125; the “ceremonial” is described in detail here.

- ↑ In a sonnet that has been handed down to us , Donato Poli placed a mocking memorial to the unfortunate Hannibal , which you can read in Bedini: Der Elefant des Pope , p. 124.

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 125.

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 135ff.

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 170ff.

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 176f.

- ↑ According to Winner: Raffael paints an elephant , p. 91f .; Oettermann's translation: Die Schaulust am Elefanten , p. 108.

- ↑ G. Scheil: The animal world in Luther's picture language , Bernburg, 1857; n. Oettermann: The curiosity about elephants , p. 108.

- ↑ See bibliographies and references at Oettermann: Die Schaulust am Elefanten and Bedini: The Pope's elephant .

- ↑ See the foreword in Bedini: The Pope's elephant .

- ^ Winner: Raffael paints an elephant , p. 81, note 82; referenced by Oettermann: The elephant curiosity .

- ↑ Lach: Elephants , p. 138, note 78.

- ^ Oettermann: Die Schaulust am Elefanten , p. 106; Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 47ff.

- ↑ P. Valeriano: Hieroglyphia sive sacris Aegyptiorum literis . Basel, 1556; fol. 21 n. Winner: Raffael paints an elephant , p. 83f. quoted n. Oettermann: Die Schaulust am Elefanten , p. 106. A mention of Tasso in his dialogues should also have had a strengthening effect.

- ↑ Valeriano n. Oettermann: Die Schaulust am Elefanten , p. 106; on Hanno's entry into Rome: Paolo Giovio (Leo X's doctor and historian): Elegia virorum belle virtute illustrium… . Basel 1575 ;, p. 229; n. Winner: Raffael paints an elephant , note 20. Paris de Grass: Il diario de Leone X. si Paride de Grassi… . Rome, 1884, p. 16; n. Winner: Raffael paints an elephant , ibid .; both quoted in Oettermann: Die Schaulust am Elefanten , p. 106; see. also the report of the Portuguese envoy Johann de Faria to Lisbon; after Rebello da Silva s. O.

- ↑ Johann de Faria, n. Rebello da Silva s. O.

- ↑ Rebello da Silva s. o., n. Winner: Raffael paints an elephant , p. 87 quoted. in Oettermann: Die Schaulust am Elefanten , p. 108.

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 186.

- ↑ Quoted in Winner: Raffael paints an elephant , p. 89 n. Oettermann: Die Schaulust am Elefanten , p. 108; see. also Bedini: Der Elefant des Pope , p. 186 and the sources referenced there.

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 104.

- ↑ Albuquerque: Cartas after Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , p. 46f.

- ↑ Bedini: Der Elefant des Pope , p. 199ff .: Memories and reflections .

- ^ Bedini does not refer to Oettermann's investigation in his bibliography; Oettermann was not translated into English. Comparable studies on historical elephants are currently only available for Soliman , the first elephant in Vienna.

- ↑ By paleontologist Frank C. Whitman Jr., Smithsonian Institution .

- ↑ Bedini: The Pope's Elephant , pp. 276–280; with a picture of the two tusks p. 279.