Experiences from the life of a slave girl

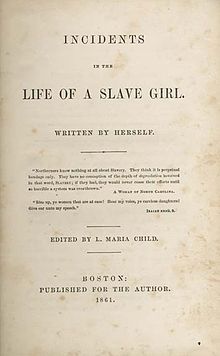

Experiences from the life of a slave girl (original title: Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl ) is an American slave narrative , which was published in 1861 by Harriet Jacobs under her pseudonym Linda Brent. The book is a detailed, chronological account of Jacobs' life as a slave and the decisions she made to gain freedom for herself and her children. Jacobs addresses the sexual abuse that slaves have been subjected to.

The manuscript was essentially written between 1853–57 while Jacobs was working as a nanny in Idlewild , the country home of writer and publisher Nathaniel Parker Willis .

Harriet Jacobs

The African American Harriet Jacobs was born as a slave in Edenton, North Carolina in 1813. Her owner taught her to read and write, which was very unusual for slaves at the time. After her death, at the age of 12, she came into the household of Dr. James Norcom, who soon began sexually harassing Harriet Jacobs. Hoping to escape Norcom's intrusiveness, Jacobs entered into a relationship with white attorney Samuel Sawyer , which resulted in two children.

In 1835, Jacobs decided to flee and hid for almost seven years in a room under the roof of her grandmother's house, which was less than a meter high. It was not until 1842 that she managed to escape to the north of the USA, where her two children and her brother could also get.

That same year she found a job as a nanny for Mary Stace Willis, wife of the writer Nathaniel Parker Willis . After the death of Mary Stace Willis, she accompanied the widower and his young daughter Imogen on a trip to England. She was positively impressed by the absence of racism, which is ubiquitous in the USA.

Harriet's brother John became increasingly involved in abolitionism; H. for the anti-slavery movement. In 1849 he took over the Anti-Slavery Office and Reading Room in Rochester, New York . His sister Harriet supported him.

The former “slave girl” without schooling found herself in circles that were preparing to change America with their - then - radical ideas and political actions. The reading room was in the same building as North Star magazine by Frederick Douglass , who is now considered the most influential African American of the 19th century. Jacobs lived with the white couple Amy and Isaac Post. Both Douglass and the Posts were staunch opponents of slavery and racial discrimination and supporters of women's suffrage.

Jacobs soon gained the trust in Amy Post, which enabled her to tell her previously secretive story. Post later described how difficult it was for the traumatized Jacobs to tell of her experiences because she suffered the pain of telling it all over again.

In 1850, Willis's second wife, Cornelia Grinnell, who had not recovered from the birth of her second child, succeeded in convincing Jacobs to return to work as a nanny for the Willis family.

Writing the autobiography

Jacobs' brother had long urged her to write down her life story. At the turn of the year 1852-53, Amy Post made the same proposal. Jacobs, despite her shame and trauma, managed to put this idea into practice.

In mid-1857 the work was finally completed to the point that she could write a letter to Amy Post to ask for a foreword. Even in this letter she mentions the shame that made it difficult for her to write the autobiography by stating that there are "many painful things" in the book that make her hesitate, someone who is "as good and pure" as Mail to ask the "victim" to associate his "name with the book."

While looking for a publisher, Jacobs initially experienced a few disappointments. Eventually she turned to Thayer and Eldridge. The publisher agreed to publish it if the well-known writer Lydia Maria Child wrote a foreword.

Jacobs and Child met in person in Boston, and Child agreed not only to write the preface but also to serve as editor. Child rearranged the material in the manuscript, mostly in chronological order, and advised that some things should be deleted and that more information should be added about the outbreaks of violence against blacks following the Nat Turner uprising of 1831. She did this in correspondence with Jacobs, but a planned second personal meeting did not take place because Cornelia Willis was going through a life-threatening pregnancy and could not do without Jacobs' help.

After the printing plates had been cast using the stereotype process , the publisher went bankrupt. Jacobs managed to buy the plates and take care of the printing and binding.

In January 1861, almost four years after the first draft was completed, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl finally appeared . The following month, the much shorter memoirs of her brother John appeared in London under the title A True Tale of Slavery . In their memories, both siblings tell both experiences and events from each other's life.

Both the first and last names of all persons have been changed in Harriet Jacobs' story, she writes under the pseudonym Linda Brent, and is regularly addressed in the book as "Linda". John (called "William" by Harriet) gives the correct first names in his book, but only mentions the first letter of all surnames, with the exception of Sawyer, whose name he initially abbreviates but later spells out in full.

Recognition as an author

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl initially met with a benevolent audience, but with the abolition of slavery in 1865, interest in the subject waned and by the late 19th century the book was largely forgotten. If it was noticed at all, then the opinion - also of the scholars - was that it was an imaginary story, which sprang from the pen of Lydia Maria Child.

It was not until the civil rights movement and the women's movement that a new interest in the book set in. The researcher Jean Fagan Yellin has been concerned with the question of the authorship of the book since the 1970s. In the estate of Amy Post and of Jacobs' slave-owning families Norcom and Horniblow, she found sufficient evidence for the authorship of Harriet Jacobs and the credibility of her statements in the autobiography. In 1987 she reissued the Incidents (which also included John Jacobs' A True Tale of Slavery ) and in 2004 a scientific biography of Harriet Jacobs.

reception

The book was promoted through the Abolitionist Network and received good reviews. Jacobs arranged for a publication in England that appeared in early 1862, soon followed by pirated printing made possible by the lack of a copyright treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States.

With the publication of the book, Harriet Jacobs did not succumb to the scorn she feared from the public, but on the contrary gained reputation. Despite the pseudonym, her authorship was soon well known, and she was regularly introduced in abolitionist circles as "Mrs. Jacobs, the author of Linda" or similar, which means that she is also addressed as "Mrs." was awarded that otherwise only married women were entitled to. The "London Daily News" wrote in early 1862 that Linda Brent was a true "heroine" who combined perseverance in the struggle for freedom with moral rectitude.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is now considered a key nineteenth-century American text in the US, is on the reading lists of many schools and colleges, and has been translated into numerous languages, including German , French, Spanish, Portuguese and Japanese.

Table of contents

Here is a summary of the main plot of Harriet Jacobs' autobiography. An overview of her life story can be found in the article Harriet Jacobs .

Linda Brent (real name: Harriet Jacobs), who was born into slavery, has the privilege of a happy childhood with her parents, which is not a matter of course for slaves. In the first six years of her life she is “so lovingly cared for that I would never have dreamed that I was a piece of commodity.” When her mother dies, six-year-old Linda is sent to her mistress. She treats them well and teaches them to read and write. Linda has fond memories of this mistress, but blames her for not having released her in her will. Instead, when her mistress dies, almost twelve-year-old Linda is given to her five-year-old niece, the daughter of doctor Dr. Flint (real name: Dr. James Norcom) is inherited. Dr. Flint soon begins making sexual advances to his slave, which also ignites his wife's jealousy and becomes an additional burden for Linda. He forbids a relationship between Linda and a free black she loves. Linda escapes into a relationship with white attorney Mr. Sands (real name: Samuel Tredwell Sawyer ), which results in Linda's children Benjamin (often called Benny; real name: Joseph Jacobs) and Ellen Brent (real name: Louisa Matilda Jacobs ). Linda is ashamed of the "sin" of entering into an illegitimate relationship, but also asks her readers not to judge their behavior by the same standards that apply to free white women protected by the law. For Linda, the baptism of her children is associated on the one hand with shame towards her dead mother, whom she herself was able to carry to the baptism as a child of a legitimate marriage. On the other hand, baptism, which takes place without the consent and knowledge of her Lord, is for Linda an act of resistance, which is expressed in the family name that she gives the children on this occasion. She does not choose - as actually intended - the name of her master, but the name of her paternal grandfather, which neither her father nor she herself was allowed to use.

When Dr. Flint threatens not only herself, but also her children, Linda hides in a tiny room under the roof of her free grandmother's house, which is less than a meter high. While her physical strength deteriorates due to the lack of exercise, she waits there for almost seven years for an opportunity to escape. Dr. Flint sells her children to a slave dealer who is supposed to resell them in another state, but who has already secretly arranged with Mr. Sands to sell the children to Sands.

Eventually Linda escapes to New York, where she finds work as a nanny for the Bruce family (in reality: Nathaniel Parker Willis and his family). There she not only has to deal with everyday racism, but also with the repeated attempts of Dr. Flints and his daughter to force them back into slavery. Reuniting with their children is not without difficulties. Finally, Mrs. Bruce secures Linda's freedom by buying Flint's daughter's rights to Linda. At the end of the book, Linda mentions the death of her grandmother, who was still happy about the news of Linda's ransom before she died.

Characters

Linda Brent is Harriet Jacobs , the narrator and protagonist.

William is John S. Jacobs , Linda's brother, who she is close to.

Aunt Martha is Molly Horniblow , Linda's maternal grandmother and her most important ally.

Emily Flint is Mary Matilda Norcom , Dr. Flint's underage daughter and Linda's owner.

Dr. Flint is Dr. James Norcom , Linda's lord, enemy and failed lover.

Mrs. Flint is Mary "Maria" Norcom , Linda's mistress and Dr. Flint's wife.

Mr. Sands is Samuel Tredwell Sawyer , Linda's white lover and father of her children, Benny and Ellen.

Ellen is Louisa Matilda Jacobs , Linda's daughter.

Mr. Bruce is Nathaniel Parker Willis , Linda's employer after the escape.

subjects

Sexual Relationships and Morals

By entering into an illegitimate relationship with Sawyer, Jacobs had violated the morality generally accepted at the time, including by herself. This is initially reflected in the behavior of those around her, which she describes in detail in her autobiography: When her grandmother receives a distorted account of Harriet Jacobs' relationships from Mrs. Norcom, she forbids her ever to enter her house again. Only a few days later, out of shame, Harriet can bring herself to tell her grandmother the whole truth, whereupon a reconciliation ensues, but this does not mean any forgiveness on the part of the grandmother. Years later, Harriet Jacobs had to face a great deal of effort to confess to her 15-year-old daughter that Sawyer was her father because she was afraid the daughter might love her less then. But her daughter has long known and assures the mother of her love. The shame about this relationship was also the reason why Jacobs, unlike her brother John, largely avoided contact with opponents of slavery after their escape in order not to have to tell their story.

The reflection on the moral concepts goes even deeper: Jacobs sees that her inner strength, which enabled her to resist Norcom, decreases when she has to admit to him and herself that she has violated it. On the other hand, she asks her readers (although she was primarily targeting women of the white middle class) not to measure the behavior of a harassed slave who is not at all protected by the law and little by the public opinion of the small town by the same standards as the behavior of free women. Jacobs succeeds in deriving a strong argument against the institution of slavery from the misconduct she has perceived and admitted: namely, that slavery morally ruins slaves.

For Sawyer, as a male member of the elite, different social norms apply: extramarital relationships with female slaves are so common in his class that they are ignored by society at all. But Sawyer also violates the behavioral patterns customary at the time, which diminishes his reputation in the eyes of his peers, but is praised by Jacobs: He confesses to a certain, limited extent to his enslaved children by buying them and giving them a path to freedom opened.

Literary influences

The book is often assigned to the genre of sensitivity because its purpose is to evoke an emotional reaction in the reader in order to sensitize him to slavery as such, although the focus is on the enslavement of women.

Jacobs was certainly familiar with Frederick Douglass' autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, to American Slave. Written by Himself (Tale of the life of FD, an American slave. Written by himself), published in 1845, four years before Jacobs and Douglass worked in the same building in Rochester. The words "Written by Herself" in the title of Jacobs' book also have the function of connecting her book to the line of tradition that Douglass belongs to.

Some episodes in Jacobs' life are reminiscent of episodes that Douglass tells: Both experience how their respective masters increasingly turn to Christianity, and are disappointed to find that he still treats them inhumanely. Another example of a parallel: A turning point in Douglass' life is that he successfully defends himself against his master who wants to whip him. Jacobs also reports an episode in which her brother John (called "William" by her) defends himself against Norcom's son who wants to whip him.

literature

- Harriet Ann Jacobs, Experiences from the Life of a Slave Girl. Translated by Petar Skunca. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform 2014. ISBN 978-1500392772

- Yellin, Jean Fagan. Harriet Jacobs: A Life . Cambridge, Massachusetts: Basic Civitas Books, 2004. ISBN 0-465-09288-8

Web links

- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl at Project Gutenberg

- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself at docsouth ( University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill )

- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl on Free Google eBook

Individual evidence

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. Cambridge (Massachusetts), pp. 102f.

- ↑ Amy Post . Rochester Regional Library Council. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ↑ "Though impelled by a natural craving for human sympathy, she passed through a baptism of suffering, even in recounting her trials to me. ... The burden of these memories lay heavily on her spirit", quoted from Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. Cambridge (Massachusetts), p. 104.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. Cambridge (Massachusetts), pp. 108-110.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. Cambridge (Massachusetts), pp. 118f.

- ↑ "as much pleasure as it would afford me and as great an honor as I would deem it to have your name associated with my Book --Yet believe me dear friend there are many painful things in it - that make me shrink from asking the sacrifice from one so good and pure as your self–. " Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. Cambridge (Massachusetts), p. 135

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. Cambridge (Massachusetts), p. 161.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. Cambridge (Massachusetts), p. 152.

- ^ A b Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. Cambridge (Massachusetts), p. 262.

- ↑ Why A 19th Century American Slave Memoir Is Becoming A Bestseller In Japan's Bookstores . Forbes.com. November 15, 2017. Retrieved November 27, 2019.

- ↑ "I was so fondly shielded did I never dreamed I was a piece of merchandise" Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 11 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]).

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 15 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]). In fact, Mary Matilda Norcom was only three years old. In her introduction, Yellin notes that while Jacobs is remarkably accurate when it comes to events in her own family's life, there is some disagreement about whites. As an example, she cites the age of Mary Matilda Norcom; see. Harriet Jacobs: Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: Written by Herself. Boston: For the Author, 1861. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1987-2000, pp. Xxix.

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 90 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]).

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 94 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]).

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 283 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]).

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. Cambridge (Massachusetts), p. 97.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. Cambridge (Massachusetts), p. 78.

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 87 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]).

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 83 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]).

- ^ Sedano Vivanco, Sonia: Literary Influences on Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself http://journals.sfu.ca/thirdspace/index.php/journal/article/viewArticle/vivanco/113# (April 27, 2014)