Harriet Jacobs

Harriet Jacobs (* 1813 or 1815 in Edenton ( North Carolina ); † 7. March 1897 in Washington, DC ) was an African-American author. Born a slave , she was sexually harassed by her owner in her youth. When he threatened to sell her children, she hid in a tiny room that she couldn't even stand in under the roof of her grandmother's house. After spending almost seven years there, she managed to escape to New York, where her children Joseph and Louisa Matilda and her brother John S. Jacobs could also end up. She found work as a nanny for the family of the then popular writer NP Willis and established contacts with the networks of the opponents of slavery and the early feminists . Her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl , published in 1861 , is now considered an "American classic".

During the American Civil War and immediately afterwards, she and her daughter organized aid for refugees from slavery and founded two schools.

Life

Origin and name

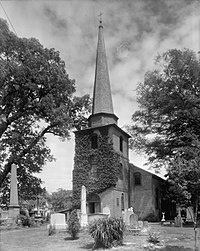

Harriet Jacobs was born in Edenton , North Carolina in 1813 to Delilah Horniblow, a slave of the Horniblow family of innkeepers. According to the law, the status of the mother as a slave or free was decisive for the status of the children ( partus sequitur ventrem - "The fruit of the womb follows the womb"), so that Harriet and her brother John, who was born two years later, were slaves to the host family from birth were valid. However, according to the same law, mother and children should have been free, since Delilah Horniblow's mother, Molly Horniblow, had been released as a child by her owner, who was also her father. But she had been kidnapped and, as a dark-skinned woman, had no realistic opportunity to seek protection from the courts. Harriet and John's father was Elijah Knox, also a slave, but who enjoyed certain privileges as a skilled carpenter. He died in 1826.

While Harriet's mother and grandmother were called Horniblow as slaves according to the family name of their owners, she took the opportunity of her children's baptism to give the children the name Jacobs, which she and her brother John took when they were freed. This baptism took place without the knowledge of Harriet's then Dr. Norcom instead. Harriet assumed that her father should have been named Jacobs since his father was Henry Jacobs, a free white man. After Harriet's mother died, her father married a free African American woman. The only child from this marriage, Harriet's half-brother, whose first name was Elijah like his father, used the surname Knox all his life, which goes back to his father's owner.

Youth as a slave

Harriet's mother died when she was six years old. She then lived with her owner, a daughter of the late innkeeper, who not only taught her to sew, but also to read and write. Very few slaves could read or write, and teaching them to do so was also prohibited by law in North Carolina in 1830. Harriet's brother John managed to teach himself to read, but he could not write when he escaped from slavery as a young adult.

The owner of Harriet and John died in 1825. In her will, she bequeathed Harriet to her 3-year-old niece, Mary Matilda Norcom. Mary Matilda's father, the doctor Dr. James Norcom (a son-in-law of the late innkeeper) therefore became Harriet's de facto master. Her brother John was bequeathed most of the property to the innkeeper's widow. Since Dr. Norcom rented it, the two siblings lived in the same household. After the innkeeper's widow died, her slaves were auctioned off at the New Year's auction in 1828, including Harriet's brother John, her grandmother Molly and her son Mark. To be auctioned off in public was a traumatic experience for 12-year-old John. Friends bought Molly Horniblow and Mark at auction with the money Molly had saved over many years and then released Molly Horniblow, while Mark could not be released due to legal regulations, but was considered a slave to his own mother for 20 years until she finally got him in 1847/48 was allowed to release. John Jacobs was bought by Dr Norcom and so stayed with his sister in his household.

That same year, Molly Horniblow's youngest son, Joseph, fled. He was brought back to Edenton in chains, jailed, and later sold to New Orleans. The family also learned that he fled from there again and reached New York. After that, contact with him was lost. For the Jacobs siblings, who talked about a possible escape as children, he became a hero, and both later named their son after him.

Norcom soon began sexually harassing Harriet Jacobs, which in turn provoked the jealousy of Norcom's wife. Norcom forbade a relationship with a free African American she had fallen in love with and who wanted to buy her free and marry. Hoping to escape Norcom's intrusiveness, Jacobs entered into a relationship with white attorney Samuel Sawyer , who was later elected to the US House of Representatives. The relationship resulted in the only two children of Harriet Jacobs, Joseph (born 1829/30) and Louisa Matilda (born 1832/33). When she found out about Jacobs' pregnancy, Norcom's wife expelled her from the house, which for Jacobs had the great advantage that she could now live with her grandmother. Norcom continued to press her on numerous visits there - he lived less than 200 m away as the crow flies.

Years in hiding

In April 1835, Norcom finally ended Jacobs' stay with her grandmother and sent her to his son's plantation 10 km away. Associated with this was the threat to first expose their children to the hard life of the plantation slaves and to sell them later - individually and without their mother. Thereupon Jacobs decided to flee in June 1835. A white woman who kept slaves hid them in her own home, despite the high personal risk involved. After a short while Jacobs was forced to dodge in a swampy area near and finally found a refuge in a small room where she could not stand upright under the roof of the house her grandmother Molly Horniblow - 9 feet (2.74 m ) long, 7 feet (2.13 m) wide, at the highest point 3 feet (91 cm) high. Here she spent almost seven years, whereby the lack of exercise caused by the tightness of the room led to a decline in her physical strength. Twenty years later, at the time of writing her autobiography, she was still suffering from the physical and mental consequences. Small light holes drilled in the roof gave her some light for reading and sewing.

After Harriet escaped, Norcom sold her brother John and their two children to a slave trader in the expectation that he would sell them to another state and thereby separate her from Harriet forever. However, the dealer had previously secretly arranged with Sawyer to resell the three to Sawyer, so that Norcom's plans for revenge were thwarted. Jacobs accuses Sawyer in her autobiography of failing to keep the promise to release their children in a legally binding form. However, Sawyer initially allowed his enslaved children to live with their great-grandmother, Molly. After his wedding in 1838, Harriet reminded him of his promise through his grandmother. He then sent Louisa Mathilda, with Harriet's consent, to his cousin in Brooklyn, New York, where slavery had already been abolished at that time, and proposed that Joseph also be sent to the free north. While locked up in the hiding place, Harriet could often watch her unsuspecting children through the light holes.

Escape and Freedom

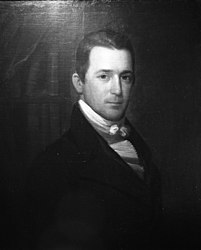

It was not until 1842 that an opportunity arose to flee by ship to Philadelphia and from there by train to New York City . Although she had no credentials, she found a job as a nanny with Mary Stace Willis, the wife of the then very popular writer Nathaniel Parker Willis . The two women initially agreed on a trial period of one week, not realizing that this would result in a 75-year relationship between the two families and not until 1917 with the death of Louisa Matilda Jacobs in the house of Edith Willis Grinnell, Nathaniel Willis' daughter from the second marriage , would end.

In 1843, Jacobs learned that Norcom was on his way to New York to bring her back by force, which law throughout the United States allowed him to do. She asked Mary Willis for two weeks off and then went to see her brother John in Boston . John had accompanied his owner Sawyer as a servant on his honeymoon through the north in 1838 and had been freed by leaving him in New York. He then hired a whaler and did not return until early 1843. From Boston, Harriet Jacobs wrote to her grandmother to send her son Joseph to see John in Boston. After Joseph arrived, she returned to work in New York. Her first employment with Willis ended in October 1843 when she learned that her whereabouts had been revealed to Norcom and she was forced to flee again to Boston. Because of the strength of the opponents of slavery there, Boston was considered relatively safe for escaped slaves. Moving to Boston also finally gave Jacobs the opportunity to remove their daughter Louisa Matilda from Sawyer's cousin's household, where she had been treated almost like a slave.

In Boston, Jacobs lived off odd jobs. Her stay there was interrupted when Mary Stace Willis died in March 1845. The widower then took Jacobs back into service to look after his daughter Imogen on a 10-month trip to England to see the parents of his late wife. The trip was a formative experience for Jacobs in two respects: On the one hand, she did not notice any racism there, with which she was repeatedly confronted in the USA. On the other hand, she experienced a renewal of her Christian faith in England, while the church officials in her homeland, who despised blacks and in some cases bought and sold slaves themselves, had repelled her.

The autobiography

Here the genesis of the autobiography is presented as part of Jacobs' life story. Information on the content of the autobiography can be found in the article Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl .

Background: Abolitionism and early feminism

Harriet's brother John became increasingly involved in abolitionism; H. for the anti-slavery movement led by William Lloyd Garrison . He went on various lecture tours, including with Frederick Douglass, who was three years his junior . In 1849 John S. Jacobs took over the "Anti-Slavery Office and Reading Room" in Rochester, New York ( Anti-Slavery Office and Reading Room). Harriet Jacobs, who no longer had to worry about her children every day (Joseph had broken off his apprenticeship as a printer after a case of racist discrimination during his mother's trip to England and went on a multi-year whaling trip; Louisa Matilda attended boarding school), supported him.

The former “slave girl” without schooling, whose horizon was previously shaped primarily by the struggle for her own survival in dignity and that of her children, now found herself in circles that were getting ready with their - then - radical ideas and their political ones Actions to change America. The reading room was in the same building as North Star magazine by Frederick Douglass, who is now considered the most influential African American of the 19th century. Jacobs lived with the white couple Amy and Isaac Post. Both Douglass and the Posts were staunch opponents of slavery and racial discrimination and supporters of women's suffrage. Douglass and Amy Post had attended the Seneca Falls Convention the year before , the world's first gathering on women's rights, and signed the Declaration of Sentiments , which called for equality between men and women.

Again work for Willis and Freikauf

Jacobs paid a visit to Nathaniel Parker Willis in New York in 1850, when she actually only wanted to see the now 8-year-old Imogen again. On this occasion, Willis' second wife, Cornelia Grinnell, who had not recovered from the birth of her second child, managed to convince her to go back to work as a nanny for the Willis family. It was clear to all concerned that this posed a considerable danger to Jacobs in view of the tightened legal situation by the recently passed Fugitive Slave Law ("Escaped Slaves Act"), and John S. made Cornelia Willis' promise not to take his sister into his hands to drop the pursuer.

In the spring of 1851 Jacobs received another message that they were looking for her. Cornelia Willis then sent Jacobs together with her (Willis') one-year-old daughter Lilian to the relatively safe Massachusetts. Jacobs, in whose autobiography the threat of separation from her own children that is constantly hanging over her and the other slaves plays an important role, spoke to her employer about the sacrifice that separation from her young daughter must mean for her. Willis then told her that the captors would have to return the child to the mother if Jacobs should fall into her hands. You can then try to save Jacobs.

In February 1852, Jacobs learned that her legal owner, the daughter of the late Norcom, had arrived with her husband at a hotel in New York, apparently with the intention of reclaiming her as a slave. Cornelia Willis then sent Jacobs back to Massachusetts with Lilian. She informed them by letter of their intention to buy them out. Jacobs turned down this offer, but Cornelia Willis bought it anyway for $ 300. In her autobiography, she clearly describes her mixed feelings: bitterness at having been sold like a commodity again, joy at the freedom that has finally been secured and great gratitude to Cornelia Willis.

Sexual Relationships: Trauma and Shame

During her stay in Rochester, Jacobs had met white people in the posts for the first time since returning from England, whom she did not despise for the color of their skin. Jacobs soon gained the trust in Amy Post, which enabled her to tell her previously secretive story. Post later described how difficult it was for the traumatized Jacobs to tell of her experiences because she suffered the pain of telling it all over again.

At the turn of the year 1852-53, Amy Post proposed Jacobs to bring her story to the public. Jacobs' brother had long urged her to do so, and she herself felt obliged to tell her story in order to contribute to the abolition of slavery and thereby spare others a similar fate.

But Jacobs had violated the then generally accepted morals - including by herself - by entering into an illegitimate relationship with Sawyer. The shame about it was the reason why Jacobs, unlike her brother John, largely avoided contact with opponents of slavery after their escape in order not to have to tell their story. Jacobs, despite her shame and trauma, managed to accept Post's suggestion. Your reply letter has been preserved and describes this struggle with yourself.

Work on the manuscript

At first Jacobs did not trust himself to write a book, so through the mediation of Amy Post and Cornelia Willis he turned to Harriet Beecher Stowe , whose novel Onkel Toms Hütte had just appeared in 1852. Her idea was that she would tell Stowe her life story and then translate it into a book. At Jacobs 'request, Post sent a summary to Stowe stating that Sawyer was the father of Jacobs' children. This information, the main reason for Jacobs' shame, Stowe passed on to Cornelia Willis, who did not yet know the origin of the children. Jacobs was outraged by this and noticed a racist undertone in Stowe's letters. Thereupon she gave up the idea of bringing her life story to the public with the help of Stowes.

In June 1853, Jacobs happened upon a defense of slavery in an old newspaper under the title The Women of England vs. the Women of America (The Women of England against the Women of America). The author, Julia Tyler , wife of the former President John Tyler , wrote in it, among other things, of "well-dressed and happy house slaves". Jacobs wrote a reply all night and sent it to the New York Tribune . This letter to the editor, published June 21, 1853, signed only "A Fugitive Slave", was her first published document. Yellin writes, "When the letter was printed ..., an author was born." (When the letter to the editor was printed, a writer was born).

In October 1853, she sent a letter to Amy Post informing her that she had decided to write her own story. A few lines earlier, she had informed Post that her grandmother had died, from which Yellin concludes that it was only the death of the strict moral standards of the grandmother who freed Jacobs to tell her story.

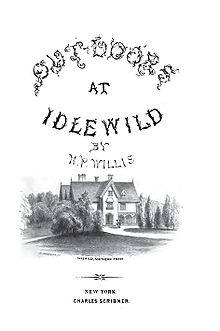

While she was writing her story in the scant free time that she had as a nanny with the Willis family, she was at their new country estate, Idlewild. Yellin captures the irony of the situation when she writes that this land sentence was deliberately designed by - the now largely forgotten - Nathaniel Parker Willis as he imagined a retreat for a famous writer, "but its owner never imagined that it was his children's nurse who would create an American classic there "(but its owner had never imagined that it would be his nanny who would write a classic of American literature there).

By mid-1857, the work was finally finished to the point that she could write a letter to Amy Post to ask for a foreword. Even in this letter she mentioned the shame that made it difficult for her to write the autobiography by saying that there were "many painful things" in the book that made her hesitate, someone who was "as good and pure" as Mail to ask the "victim" to associate his "name with the book."

Search for a publisher

In May 1858, Harriet Jacobs left for England, where she hoped to find a publisher for her manuscript. Despite good letters of recommendation, the publication in England ultimately failed. The reason for this failure is not entirely clear. Yellin suspects that her contacts among the British abolitionists feared that the book would meet with opposition from audiences in prudish Victorian England because of her relationship with Sawyer, and advised her to first publish the book in the USA. Discouraged, she returned to Idlewild after a few months and did nothing for a year to bring her manuscript to the public.

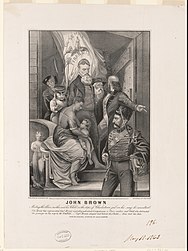

On October 16, 1859, the opponent of slavery, John Brown , made a poorly planned and unsuccessful attempt to unleash a revolt by the slaves with his attack on Harper's Ferry . Brown, who was hanged in December, became a hero to many abolitionists. Jacobs added a final chapter to her manuscript, which Brown paid tribute to. She sent this manuscript to the Phillips and Samson publishing house in Boston. The publisher wanted to publish it, but stipulated that either Nathaniel Parker Willis or Harriet Beecher Stowe should write a foreword. Willis, who, unlike his two wives, was an advocate of slavery, refused to ask, and Stowe refused. When the publisher went bankrupt, the second attempt at publication had also failed.

Jacobs made another attempt with Thayer and Eldridge, who had just published a very kind biography of John Brown. Thayer and Eldridge agreed to publish it if the well-known writer Lydia Maria Child wrote a foreword. Jacobs confessed to Amy Post how difficult it was for her to seek help from a well-known writer again after being rejected by Stowe, but she was ready to try one last effort.

Edited by Lydia Maria Child

Jacobs and Child met in person in Boston, and Child agreed not only to write the preface but also to serve as editor. Child rearranged the material in the manuscript, mostly in chronological order, advising that the chapter on Brown should be deleted and that more information on the outbreaks of violence against blacks after the Nat Turner uprising of 1831 should be added. She did this in correspondence with Jacobs, but a planned second personal meeting did not take place because Cornelia Willis was going through a life-threatening pregnancy and could not do without Jacobs' help.

After the printing plates were cast using the stereotype process , the second publisher also went bankrupt. Jacobs managed to buy the plates and take care of the printing and binding.

In January 1861, almost four years after the first draft was completed, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl finally appeared . The following month, the much shorter memoirs of her brother John appeared in London under the title A True Tale of Slavery . In their memories, both siblings tell both experiences and events from each other's life.

Both the first and last names of all persons have been changed in Harriet Jacobs' story, she writes under the pseudonym Linda Brent, and is regularly addressed in the book as "Linda". John (called "William" by Harriet) gives the correct first names in his book, but only mentions the first letter of all surnames, with the exception of Sawyer, whose name he initially abbreviates but later spells out in full.

reception

The book was promoted through the Abolitionist Network and received good reviews. Jacobs arranged for a publication in England that appeared in early 1862, soon followed by pirated printing made possible by the lack of a copyright treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States.

With the publication of the book, Harriet Jacobs did not succumb to the scorn she feared from the public, but on the contrary gained reputation. Despite the pseudonym, her authorship was soon well known, and she was regularly referred to in abolitionist circles as “Mrs. Jacobs, the author of Linda "or similar, with which she was also given the title" Mrs. ", which otherwise only married women were entitled to. The London Daily News wrote in early 1862 that Linda Brent was a true "heroine" who combined perseverance in the struggle for freedom with moral rectitude.

Civil War and Post War

Refugee aid and politics

After Abraham Lincoln was elected president in November 1861, the issue of slavery led to the secession of the southern United States and then to civil war . Numerous African Americans who escaped slavery in the south gathered north of the front. As the Lincoln government continued to regard the slaves as the property of their owners, these refugees were normally considered contraband of war (confiscated enemy property). The name contrabands soon caught on. Some of them vegetated under the most pitiful conditions in makeshift refugee camps. Jacobs had actually planned to follow in her brother's footsteps as a speaker against slavery, but now saw her job as helping the contrabands .

To this end, Harriet Jacobs went to Washington, DC and neighboring Alexandria, Virginia in the spring of 1862 . She summarized the experiences of the first few months in the report Life among the Contrabands , which appeared in Garrison's magazine The Liberator in September , the author being named “Mrs. Jacobs, the author of 'Linda' ”(Mrs. Jacobs, the author of 'Linda') was introduced. This report is on the one hand a description of the refugee misery with the request for donations, on the other hand it is also a political accusation against the institution of slavery. Jacobs emphasizes that the former slaves will be able to build their own lives independently if they get the necessary support.

During the fall of 1862 she traveled north to use the popularity of the book to build a network to support her work. She officially appeared as an employee of the New York Friends ( Quakers in New York).

From January 1863 onwards, the focus of her work was in Alexandria. Together with the Quaker Julia Wilbur, a teacher, feminist and abolitionist who she had already met in Rochester, she distributed relief supplies and fought against incompetent, overwhelmed or openly racist authorities.

In addition to specific auxiliary work, Jacobs was also active on the political level. In late May 1863 she attended the New England Anti-Slavery Society's annual conference in Boston. Along with the other conference participants, she cheered the newly formed 54th Infantry Regiment, which consisted of black soldiers led by white officers. Since the US government had rejected the use of African American soldiers just a few months earlier, it was an event of great symbolic power. In a letter to Lydia Maria Child, Jacobs expressed her joy and pride that "my poor, oppressed race would pull a prank for freedom."

The Jacobs School

In most slave states, it was forbidden to teach slaves to read and write before the civil war. In Virginia this ban even extended to free blacks. After the invasion of the Union troops in 1861, a few schools were opened in Alexandria that also accepted blacks, but initially there was no free school under Afro-American control. Jacobs now supported a school project that arose out of the black community in the course of 1863. In the fall of 1863, Jacobs' daughter Louisa Matilda, who was trained as a teacher, came to Alexandria with Virginia Lawton, a black friend of the Jacobs family. After some conflicts with white missionaries from the north who wanted to take control of the school, the Jacobs School was able to begin its work in January 1864 under the direction of Louisa Matilda. Harriet Jacobs wrote that she did not advocate control by the black community out of an aversion to white teachers. But the former slaves, who had been raised to always look up to their white masters, would now begin to develop "respect for their own race".

The work in Alexandria brought Jacobs local and national recognition, especially among the abolitionists: In the spring of 1864 she was elected to the executive committee of the Women's Loyal National League , a women's organization founded in 1863 by Susan B. Anthony The task was to collect signatures for the abolition of slavery through a constitutional amendment . On August 1, 1864, she was the keynote speaker in front of the Afro-American soldiers at a hospital in Alexandria on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the liberation of slaves in the English colonies. Numerous abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, paid a visit to Jacob on their travels in the south. She also found the work personally delightful. In early December 1862 she had written to Amy Post that the past six months had been the happiest of her entire life.

Working with ex-slaves in Savannah

Mother and daughter Jacobs continued their work in Alexandria until after the Union won the Civil War. Under the impression that the former slaves in Alexandria could now take care of themselves, they followed a call from an aid organization in New England looking for teachers for the freed slaves in Georgia . In November 1865 they arrived in Savannah, Georgia , which had only seen the invasion of Union troops and the liberation of the slaves 11 months earlier. Over the next few months, they distributed clothes and set about building a school, an orphanage, and an old people's home.

The political situation had changed in the meantime, however: After the murder of Lincoln, Andrew Johnson, a southerner and former slave owner, had become president. On the orders of the President, numerous former slaves were driven back from the land that the army had given them a year earlier. The land question and the unjust labor contracts that the former masters forced on their former slaves with the support of the army played an important role in Jacobs' reports from Georgia.

As early as July 1866, mother and daughter Jacobs left Savannah, which was increasingly marked by violence against the blacks. Harriet Jacobs went back to Idlewild to help Cornelia Willis take care of her terminally ill husband, who died in January 1867.

After a visit to Edenton in the spring of 1867, where only the widow of her uncle Mark remained of her family, Jacobs traveled to Great Britain for the last time at the end of the year to raise funds for the homes in Savannah, the construction of which was not beyond the planning stage in 1866 got out. On her return, however, she had to realize that the terror against the blacks prevailing in Georgia, which was partly organized by the Ku Klux Klan , made these projects impossible. The money raised was donated to the New York Friends home fund .

In the 1860s, Jacobs was struck by a personal tragedy: in the early 1850s, their son Joseph went to California with his uncle John and later to Australia to try his luck as a gold digger. John Jacobs later moved on to England while Joseph stayed in Australia. When the correspondence with his mother was broken, she had a search report read out in Australian churches - mediated through acquaintances - without ever being able to find out anything about her son's whereabouts.

Old age and death

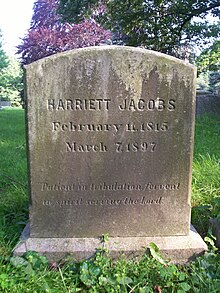

After her return from England, Jacobs withdrew largely from the public. Together with her daughter Louisa, she ran a boarding house in Cambridge, Massachusetts , in which, among others, professors from Harvard University lived. Her brother John returned from England in 1873 and moved into the neighborhood with his English wife, son Joseph and two of his wife's children from a previous relationship, but died in December 1873. In 1877 Harriet and Louisa Jacobs moved to Washington, DC, where Louisa was hoping for a job as a teacher. But Louisa only found work for a short time; Mother and daughter ran a boarding house again until Jacobs fell so seriously ill in 1887/88 that she had to give up this activity. With odd jobs and the help of friends, including Cornelia Willis, the two struggled to stay afloat. Harriet Jacobs died in Washington, DC on March 7, 1897, and was buried next to her brother in Mount Auburn Cemetery , Cambridge. Her tombstone bears the biblical inscription: "Patient in tribulation, fervent in spirit serving the Lord". ("Patient in distress, burning in the spirit serving the Lord.", Cf. Romans 12: 11f)

Aftermath

Colson Whitehead mentions Jacobs in the "Acknowledgments" of his 2016 bestseller The Underground Railroad : "Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs, obviously." (Of course, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs). Cora, the heroine of this novel, has to hide in an attic in Jacobs' home state of North Carolina, where, like Jacobs, she cannot even stand upright, and from where, like Jacobs, she watches life outside through a hole that a previous user of the hiding place had drilled from the inside.

Timeline: Harriet Jacobs, Abolitionism and Literature

| year | Jacobs and her family | Politics and literature |

| 1809 | Birth of Edgar Allan Poe and Abraham Lincoln . | |

| 1811 | Birth of Harriet Beecher Stowe . | |

| 1812 | British-American War . | |

| 1813 | Harriet Jacobs is born. | |

| 1815 | Harriet's brother John S. Jacobs is born . | |

| 1816 | Creation of the American Colonization Society to relocate free African Americans to Africa. | |

| 1817 | Birth of Henry David Thoreau . | |

| 1818 | Birth of Frederick Douglass . | |

| 1819 | Death of Jacobs' mother. | Birth of Walt Whitman and Herman Melville . |

| 1825 | Jacobs' owner dies and leaves her to the little daughter of Dr. Norcom. | |

|

1826 |

Death of Jacobs' father. | Death of Thomas Jefferson . His slaves are sold to pay off his debts. |

| 1828 | Jacobs' grandmother is bought by a friend and then released.

Jacobs' uncle Joseph escapes, is brought back in chains and escapes again. |

|

|

1829 |

Birth of Jacobs' son Joseph. | Inauguration of Andrew Jackson as 7th US President. |

| 1831 |

Nat Turner's slave revolt in Virginia.

William Lloyd Garrison begins publishing his magazine The Liberator . |

|

| 1833 | Daughter Louisa Matilda Jacobs is born . | |

| 1834 | Abolition of slavery in the British colonies. | |

| 1835 | Harriet Jacobs is hiding in her grandmother's house. | Birth of Mark Twain . |

| 1836 | Beginning of the 2nd year in hiding. Sawyer , the father of Jacobs' children, is elected Congressman. | |

| 1837 | Beginning of the 3rd year in hiding. | The " Gag Rule " introduced in Congress to prevent discussions about slavery.

EP Lovejoy , editor of an abolitionist magazine, is lynched in Alton, Illinois. |

| 1838 | Beginning of the 4th year in hiding. Sawyer gets married in Chicago. John S. Jacobs gains freedom. | A few weeks before John S. Jacobs, Frederick Douglass gains his freedom (through escape). |

| 1839 | Beginning of the 5th year in hiding. John S. Jacobs goes whaling. | Slaves seize the slave ship La Amistad .

Theodore Dwight Weld publishes American Slavery As It Is , a testimony-based indictment against slavery. |

| 1840 | Beginning of the 6th year in hiding. John S. still on whaling. | |

| 1841 | Beginning of the 7th and final year in hiding. John S. still on whaling. | Herman Melville goes whaling. He later processed his experiences in his book Moby-Dick . |

| 1842 | Harriet Jacobs escapes to the north. In New York she finds work as a nanny for the writer NPWillis.

John S. still on whaling. |

|

| 1843 | John S. Jacobs returns and settles in Boston.

Harriet Jacobs has to flee New York. In Boston, she is reunited with her two children and her brother. |

|

| 1845 | Harriet Jacobs travels to England as a nanny for Imogen Willis. |

The Baptists are split into a northern and a southern group because of the slavery issue.

Edgar Allan Poes published The Raven . |

| 1846 | Declaration of war on Mexico . | |

| 1848 | End of the war against Mexico .

Seneca Falls Convention on Women's Rights. |

|

|

1849 |

Harriet Jacobs moves to Rochester. Beginning of her friendship with Amy Post . | Thoreau writes Civil Disobedience . |

| 1850 | Harriet Jacobs starts working again as a nanny for the Willis family. Her brother John S. goes to California, later to Australia and finally to England. | Fugitive slave law . |

| 1851 | Herman Melville writes Moby-Dick . | |

| 1852 | Cornelia Willis buys Harriet Jacobs 'legal owners' rights. | Harriet Beecher Stowe writes Uncle Tom's Cabin . |

| 1853 | Death of Jacobs' grandmother. An anonymous letter to the editor to a New York newspaper is their first publication. She starts working on incidents . | |

| 1854 | Kansas-Nebraska Act . | |

| 1856 | The slavery issue leads to overt violence in Kansas (" Bleeding Kansas "). | |

| 1857 | Dred Scott Case in the Supreme Court : Blacks "had no rights that whites had to respect". | |

| 1858 | Jacobs completes the manuscript of Incidents . She looks in vain for a publisher in England. | |

| 1859 |

John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry.

Supreme Court declares the constitutionality of the Fugitive Slave Law . |

|

| 1860 | Lydia Maria Child becomes editor for Incidents . | Abraham Lincoln was elected 16th President (November 7th). South Carolina leaves the Union (December 20). |

| 1861 | Publication of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (January). | Davis is sworn in as President of the Confederation (February 18).

Inauguration of Abraham Lincoln (March 4th). Attack on Fort Sumter (April 12th). Beginning of the civil war . |

| 1862 | Harriet Jacobs organizes aid for escaped slaves in Washington, DC and Alexandria, Virginia. | |

| 1863 | Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation .

Victories of the Union troops at Gettysburg and Vicksburg . |

|

| 1864 | Jacobs School opens in Alexandria. | |

| 1865 | Harriet and Louisa Matilda Jacobs go to Savannah, Georgia to organize help for the former slaves. | Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House .

Assassination of Abraham Lincoln . Abolition of slavery by the 13th amendment to the constitution . |

| 1866 | Harriet and Louisa Matilda Jacobs leave Savannah. Harriet helps Cornelia Willis to take care of her terminally ill husband. | |

| 1867 | Jacobs travels to England to raise money for her projects in Savannah. | |

| 1868 | Jacobs returns from England and retires into private life. | |

| 1873 | John S. Jacobs returns to the United States and settles near his sister. He dies on December 19th. | |

| 1897 | March 7: Harriet Jacobs dies in Washington, DC |

literature

- Harriet Ann Jacobs: Experiences from the life of a slave girl . Translated by Petar Skunca. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014. ISBN 978-1-5003-9277-2 .

- Harriet Jacobs: Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: Written by Herself . Boston: For the Author, 1861. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1987-2000. ISBN 978-0-6740-0271-5 .

- Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs: A Life . New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2004. ISBN 0-465-09288-8 .

- Jean Fagan Yellin (ed.): The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers . The University of North Carolina Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8078-3131-1 .

Web links

- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . Boston: Published for the Author, 1861.

- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl . Critical edition ed. Julie R. Adams, with introduction and resources for teachers and students. American Studies at the University of Virginia.

- Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl . From The Multiracial Activist

- A True Tale of Slavery John Jacobs

- Some links on a Washington State University page

- Selected Writings and Correspondence: Harriet Jacobs. Collection of materials including original transcribed letters from Harriet Jacobs, Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition, Yale University

- Harriet Jacobs Historic Marker. North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program

- LETTER FROM A FUGITIVE SLAVE. From New York Daily Tribune New York, June 21, 1853, p. 6th

Individual evidence

- ↑ Many editions of her autobiography give her name as "Harriet A. Jacobs" or "Harriet Ann Jacobs". Her biographer and editor Jean Fagan Yellin also uses “Harriet A. Jacobs” as the author's name for the edition of her autobiography (Cambridge (Massachusetts) and London 2000) that she has obtained. In the index of this issue, Jacobs is listed as “Jacobs, Harriet Ann” (on p. 330). In the 2004 biography Harriet Jacobs. A Life , however, Yellin only uses the name "Harriet Jacobs" (in the register on p.384 corresponding to "Jacobs, Harriet"). In none of the numerous documents cited in both books is a middle name "Ann" found. Also on the tombstone is only "Harriet Jacobs".

- ↑ Your biographer Yellin, who has examined numerous documents about Jacobs and her family in Edenton, names 1813 as the year of birth, without giving any precise details on the day, month or even season; see. Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 3. However, her tombstone gives the date of birth February 11, 1815 (see photo at the end of this article). Mary Maillard, who edited Jacobs' daughter's letters in 2017, argues that 1815 was the year of birth in an article published in 2013: Dating Harriet Jacobs: Why Birthdates Matter to Historians . Black past. Retrieved March 21, 2020. The dates and ages in this article will follow Yellin.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York 2004, p. 126.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 40 (baptism of children), 53 (Norcom in various church functions), 72 (Molly Horniblow as "communicant"); Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 115, 120 f . (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]). : Dr. Norcom (here called "Dr. Flint") as "communicant" p.115; Baptism of Harriet Jacobs and her children p.120f.

- ↑ The ownership structure was complicated: John Horniblow had died in 1799. His widow Elizabeth Horniblow continued to run the restaurant and initially kept Molly Horniblow and her children as slaves. Molly's daughter Delilah passed it on to her unmarried, disabled daughter Margaret, who thereby also became the first owner of Delilah's children Harriet and John Jacobs; Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 6.

- ↑ The difficulties blacks faced in similar situations a few decades later are e.g. B. Described in: Judson Crump and Alfred L. Brophy: Twenty-One Months a Slave: Cornelius Sinclair's Odyssey . In: Mississippi Law Journal . No. 86 . The Faculty Lounge, 2017, p. 457-512 (English, typepad.com [PDF]).

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 92.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 121 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]). Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 40.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 14, 223, 224.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 35.

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 94 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]).

- ^ A True Tale of Slavery . S. 126 (English, unc.edu [accessed November 29, 2019]).

- ^ A True Tale of Slavery . S. 86 (English, unc.edu [accessed November 29, 2019]).

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 363 (note on p. 254).

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 20-21.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 33, 351 (note on p. 224).

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 33, 351 (note on p. 224).

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 278 (note on p. 39).

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 28, 31.

- ↑ The city map shows Edenton in 2019, but the course of the streets does not differ from the situation in the 1830s. The names of the streets have also remained the same except for today's additions "East" and "West". See Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, illustration Map of Edenton between pp. 266 and 267.

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 129 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]).

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 173 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]).

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 224 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]).

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 253 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]).

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 224 f . (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]).

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 70, 265.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 72.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 74.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 68f, 74.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 77f, 87.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 83-87.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 98.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 102f.

- ↑ Amy Post . Rochester Regional Library Council. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 108-110.

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 291 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]).

- ^ Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Written by Herself . S. 300–303 (English, unc.edu [accessed September 19, 2019]). - Corresponds to p. 200f in H. Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Ed. JFYellin, Cambridge 2000.

- ↑ "Though impelled by a natural craving for human sympathy, she passed through a baptism of suffering, even in recounting her trials to me. ... The burden of these memories lay heavily on her spirit", quoted from Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 104.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 78.

- ↑ The transcription of the letter can be found in the appendix to: Harriet Jacobs: Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: Written by Herself. Cambridge 2000, pp. 253-255. Summary in: Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 118f.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 119-121.

- ↑ LETTER FROM A FUGITIVE SLAVE. Slaves Sold under Peculiar Circumstances . (English, unc.edu [accessed December 7, 2019]).

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 122f.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 124-126.

- ↑ "... when NPWillis is mentioned today it is generally as a footnote to some else's story."; Baker, Thomas N. Sentiment and Celebrity: Nathaniel Parker Willis and the Trials of Literary Fame. New York, Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-19-512073-6 , p. 4.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 126.

- ↑ "as much pleasure as it would afford me and as great an honor as I would deem it to have your name associated with my Book --Yet believe me dear friend there are many painful things in it - that make me shrink from asking the sacrifice from one so good and pure as your self–. " Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 135.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 136-139.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 140.

- ^ The Public Life of Capt. John Brown by James Redpath.

- ^ Letter from Jacobs to Post, October 8, 1860, cf. Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 140 and note on p. 314.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 161.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 152.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 157.

- ^ Life among the Contrabands . (English, unc.edu [accessed December 22, 2019]). Summary of the report in: Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 159-161.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 161f.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 164.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 164-174.

- ↑ English: 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment . For the symbolic and political significance of this regiment, see David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass. Prophet of Freedom. New York 2018, pp. 388-402, especially p. 398.

- ↑ "How my heart swelled with the thought that my poor oppressed race were to strike a blow for freedom!" quoted from: Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 168-169.

- ↑ "respect for their race", H. Jacob an LMChild, published in the National Anti-Slavery Standard under the title Letter from Teachers of the Freedmen . April 16, 1864 (English, unc.edu [accessed December 31, 2019]). quoted from Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 177.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 176-178.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 175-176.

- ^ "British West Indian Emancipation", an annual celebration celebrated by the abolitionists, which was supposed to show the USA their backwardness compared to Great Britain.

- ↑ David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass. Prophet of Freedom. New York 2018, p. 418. It is the only mention of Jacobs in this book, while Douglass in Yellin, Harriet Jacobs, is mentioned on a total of 30 pages according to the register.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 181-183.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 162, cf. also p. 167.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 186.

- ↑ The organization was called New England Freedmen's Aid Society ( New England aid society for the freed slaves).

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 190-194.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 191-195.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 200-202.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 210f, 217 with note on p.345.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 224f.

- ^ Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, pp. 217-261.

- ^ Colson Whitehead, The Underground Railroad. London 2017, p. 185. The parallel is mentioned by Martin Ebel in the Schweizer Tages-Anzeiger , How slaves escaped their fate. .

- ↑ Harriet Jacobs: Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: Written by Herself. Cambridge 2000, pp. 245-247.

- ↑ Timeline . (English, archive.org [accessed January 15, 2020]).

- ^ Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning. The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. New York: Nation Books 2016. ISBN 978-1-5685-8464-5 , p. 157.

- ↑ According to Yellin's timetable in Harriet Jacobs: Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: Written by Herself. Cambridge 2000, p. 246, the escape took place in 1844. But in her biography of Jacobs, published in 2004, Yellin offers a detailed description of the escape that took place a few days after "one Sunday morning in late October" 1843. Jean Fagan Yellin: Harriet Jacobs. A life. New York 2004, p. 74.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Jacobs, Harriet |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Jacobs, Harriet Ann (in question); Brent, Linda (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | African American author |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1813 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Edenton , North Carolina |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 7, 1897 |

| Place of death | Washington, DC |