Intonation (keyboard instruments)

Intonation of keyboard instruments describes the precise coordination of timbre and volume by the instrument maker.

Intonation of harpsichords

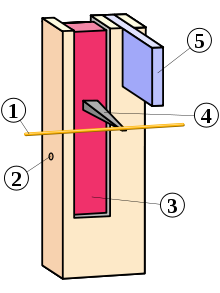

Harpsichords are voiced by cutting the plectra . The picks protruding across the jumpers tear the strings by first lifting them, bending them under them and thereby letting them slip sideways. Their elasticity therefore determines the sound of the harpsichord.

Picks were originally made from bird feathers (hence the earlier name "quill"; this material is rarely used today), today they are mostly made of Delrin , often leather. Their exact elasticity depends not only on the material but also on the shape: the thinner they are, the faster they give in, the quieter the tone and the softer the touch. They are cut to the correct shape, length and thickness with a scalpel. Since the distance between the jumpers and the strings differs minimally, the picks are always voiced specifically for a certain jumper and a certain string. Too hard intonation (too thick or too long plectra) leads to excessive demands on the instrument; the sound begins to rattle, and too much finger force has to be applied to overcome the pressure point at which the pick tears the string. If the intonation is too soft, the soundboard does not vibrate sufficiently, the tone remains dull and is not stable.

With every harpsichord, all picks have to be replaced every few years, as the material loses its elasticity over time. Many harpsichordists do this work themselves because, provided that the jumper is handled carefully, hardly anything can be destroyed: a cut pick is simply replaced by a new one.

Intonation of pianos with hammer action

Pianos are voiced by working the hammer heads. The sound of the strings is influenced by the hardness of the hammer felt (the harder, the louder) and by its elasticity, i.e. H. the time in which it returns to its original shape after a deformation (the more elastic, the richer in overtones - brighter - the sound). A prerequisite for the intonation is a perfectly regulated mechanism. All hammer heads must be exactly straight in order to strike all chores equally, and they must be firmly glued to the hammer handles, otherwise the hammer heads will move slightly to the side when they hit the strings and the sound will be deaf. New hammer heads are not exactly flat at the front; Hammer heads that have been played a lot have grooves due to the constant hitting the string. The hammer heads are first filed into shape ("peeled off"). Both new and much-played hammerheads are too hard. In order to loosen it, the intoneur pierces the felt with needles at specific points. If you hit it gently, only the top layer of the felt produces the sound; the stronger the attack, the deeper layers contribute to the sound. Therefore, the different layers of the felt are voiced differently by different stitch directions and depths in order to give the instrument the greatest possible wealth of dynamic and tonal shades.

Difficulties often arise at the transition from the three-choir string to the two-choir and from there to the single-choir, as the timbre of the instrument can change here due to the thicker strings. The cross-stringing common in today's instruments, in which the tenor strings (on the grand piano) lead diagonally to the left and the bass strings are stretched diagonally across to the rear wall bend, often leads to a tonal break between tenor and bass strings. These breaks must be covered as far as possible by the intonation.

The ideal intonation of an instrument always depends on the room in which it is located. In a small living room where carpets, curtains, lots of furniture, bookshelves, etc. prevent reflections and thereby stifle the sound, the intonation must be sharper. In a room of the same size, which by itself produces a more sustaining sound through a wooden floor and some free wall surfaces, the intonation is much more reserved. In concert halls, the intonation is sharper so that the instrument can assert itself over a greater distance and against an orchestra. The major piano manufacturers therefore always intone their instruments in special rooms that reflect the acoustic conditions of the presumed destination. Ideally, however, an instrument is only finally voiced at its final location.

The regulation and voicing of grand pianos and upright pianos is carried out by trained specialists. Unprofessionally engraved hammer heads may have to be replaced or re-felted, which is tedious and expensive, since they are designed specifically for the instrument in terms of shape and weight.

literature

- Otto Funke, The voicing of pianos and grand pianos . Frankfurt / Main (Verlag Erwin Bochinsky) 2nd edition 1977 (1st edition 1953).

- Herbert Junghanns, The piano and grand piano construction . Frankfurt / Main (Verlag Erwin Bochinsky) 7th, improved and significantly expanded edition 1991.

- Ingbert Blüthner-Haessler, Pianofortebau. Elementary and comprehensively presented by a piano maker . Frankfurt / Main (Verlag Erwin Bochinsky) 1991.

- Ulrich Laible, specialist piano construction , volume 1. Frankfurt / Main (Verlag Erwin Bochinsky) 2nd edition 1993.

- Gerhard Krämer, harpsichord - design and build yourself. A guide for DIY enthusiasts . Edition Merseburger 1995.

See also

- For the intonation of organs, see organ pipe